eBook - ePub

Change by Design

How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Change by Design, Tim Brown, CEO of IDEO, the celebrated innovation and design firm, shows how the techniques and strategies of design belong at every level of business. Change by Design is not a book by designers for designers; this is a book for creative leaders who seek to infuse design thinking into every level of an organization, product, or service to drive new alternatives for business and society.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

what is design thinking?

CHAPTER ONE

getting under your skin,

or how design thinking is about more than style

In 2004 Shimano, a leading Japanese manufacturer of bicycle components, was experiencing flattening growth in its traditional high-end road racing and mountain bike segments in the United States. The company had always relied on new technology to drive its growth. It had invested heavily in an effort to anticipate the next innovation. In the face of the changing market it seemed prudent to try something new, so Shimano invited IDEO to collaborate.

What followed was an exercise in designer-client relations that looked very different from what such an engagement might have looked like a few decades or even a few years earlier. Shimano did not hand us a list of technical specifications and a binder full of market research and send us off to design a bunch of parts. Rather, we joined forces and set out together to explore the changing terrain of the cycling market.

During the initial phase, we fielded an interdisciplinary team of designers, behavioral scientists, marketers, and engineers whose task was to identify appropriate constraints for the project. The team began with a hunch that it should not focus on the high-end market. Instead, they fanned out to learn why 90 percent of American adults don’t ride bikes—despite the fact that 90 percent of them did as kids! Looking for new ways to think about the problem, they spent time with consumers from across the spectrum. They discovered that nearly everyone they met had happy memories of being a kid on a bike but many are deterred by cycling today—by the retail experience (including the intimidating, Lycra-clad athletes who serve as sales staff in most independent bike stores); by the bewildering complexity and excessive cost of the bikes, accessories, and specialized clothing; by the danger of cycling on roads not designed for bicycles; and by the demands of maintaining a sophisticated machine that might be ridden only on weekends. They noted that everyone they talked to seemed to have a bike in the garage with a flat tire or a broken cable.

This human-centered exploration—which looked for insights from bicycle aficionados but also, more important, from people outside Shimano’s core customer base—led to the realization that a whole new category of bicycling might reconnect American consumers to their experiences as children. A huge, untapped market began to take shape before their eyes.

The design team, inspired by the old Schwinn coaster bikes that everyone seemed to remember, came up with the concept of “coasting.” Coasting would entice lapsed bikers back into an activity that was simple, straightforward, healthy, and fun. Coasting bikes, built more for pleasure than for sport, would have no controls on the handlebars, no cables snaking along the frame, no nest of precision gears to be cleaned, adjusted, repaired, and replaced. As we remember from our earliest bikes, the brakes would be applied by backpedaling. Coasting bikes would feature comfortable padded seats, upright handlebars, and puncture-resistant tires and require almost no maintenance. But this is not simply a retrobike: it incorporates sophisticated engineering with an automatic transmission that shifts the gears as the bicycle gains speed or slows.

Three major manufacturers—Trek, Raleigh, and Giant—began to develop new bikes incorporating innovative components from Shimano, but the team didn’t stop there. Designers might have ended the project with the bike itself, but as holistic design thinkers they pressed ahead. They created in-store retailing strategies for independent bike dealers, in part to mitigate the discomfort that novices felt in retail settings built to serve enthusiasts. The team developed a brand that identified coasting as a way to enjoy life (“Chill. Explore. Dawdle. Lollygag. First one there’s a rotten egg.”). In collaboration with local governments and cycling organizations, it designed a public relations campaign including a Web site that identified safe places to ride.

Many other people and organizations became involved in the project as it passed from inspiration through ideation and on into the implementation phase. Remarkably, the first problem the designers would have been expected to address—the look of the bikes—was deferred to a late stage in the development process, when the team created a “reference design” to show what was possible and to inspire the bicycle manufacturers’ own design teams. Within a year of the bike’s successful launch, seven more manufacturers had signed up to produce coasting bikes. An exercise in design had become an exercise in design thinking.

three spaces of innovation

Although I would love to provide a simple, easy-to-follow recipe that would ensure that every project ends as successfully as this one, the nature of design thinking makes that impossible. In contrast to the champions of scientific management at the beginning of the last century, design thinkers know that there is no “one best way” to move through the process. There are useful starting points and helpful landmarks along the way, but the continuum of innovation is best thought of as a system of overlapping spaces rather than a sequence of orderly steps. We can think of them as inspiration, the problem or opportunity that motivates the search for solutions; ideation, the process of generating, developing, and testing ideas; and implementation, the path that leads from the project room to the market. Projects may loop back through these spaces more than once as the team refines its ideas and explores new directions.

The reason for the iterative, nonlinear nature of the journey is not that design thinkers are disorganized or undisciplined but that design thinking is fundamentally an exploratory process; done right, it will invariably make unexpected discoveries along the way, and it would be foolish not to find out where they lead. Often these discoveries can be integrated into the ongoing process without disruption. At other times the discovery will motivate the team to revisit some of its most basic assumptions. While testing a prototype, for instance, consumers may provide us with insights that point to a more interesting, more promising, and potentially more profitable market opening up in front of us. Insights of this sort should inspire us to refine or rethink our assumptions rather than press onward in adherence to an original plan. To borrow the language of the computer industry, this approach should be seen not as a system reset but as a meaningful upgrade.

The risk of such an iterative approach is that it appears to extend the time it takes to get an idea to market, but this is often a shortsighted perception. To the contrary, a team that understands what is happening will not feel bound to take the next logical step along an ultimately unproductive path. We have seen many projects killed by management because it became clear that the ideas were not good enough. When a project is terminated after months or even years, it can be devastating in terms of both money and morale. A nimble team of design thinkers will have been prototyping from day one and self-correcting along the way. As we say at IDEO, “Fail early to succeed sooner.”

Insofar as it is open-ended, open-minded, and iterative, a process fed by design thinking will feel chaotic to those experiencing it for the first time. But over the life of a project, it invariably comes to make sense and achieves results that differ markedly from the linear, milestone-based processes that define traditional business practices. In any case, predictability leads to boredom and boredom leads to the loss of talented people. It also leads to results that rivals find easy to copy. It is better to take an experimental approach: share processes, encourage the collective ownership of ideas, and enable teams to learn from one another.

A second way to think about the overlapping spaces of innovation is in terms of boundaries. To an artist in pursuit of beauty or a scientist in search of truth, the bounds of a project may appear as unwelcome constraints. But the mark of a designer, as the legendary Charles Eames said often, is a willing embrace of constraints.

Without constraints design cannot happen, and the best design—a precision medical device or emergency shelter for disaster victims—is often carried out within quite severe constraints. For less extreme cases we need only look at Target’s success in bringing design within the reach of a broader population for significantly less cost than had previously been achieved. It is actually much more difficult for an accomplished designer such as Michael Graves to create a collection of low-cost kitchen implements or Isaac Mizrahi a line of ready-to-wear clothing than it is to design a teakettle that will sell in a museum store for hundreds of dollars or a dress that will sell in a boutique for thousands.

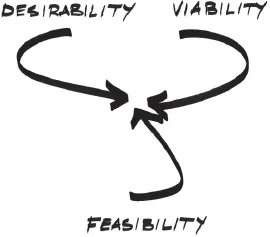

The willing and even enthusiastic acceptance of competing constraints is the foundation of design thinking. The first stage of the design process is often about discovering which constraints are important and establishing a framework for evaluating them. Constraints can best be visualized in terms of three overlapping criteria for successful ideas: feasibility (what is functionally possible within the foreseeable future); viability (what is likely to become part of a sustainable business model); and desirability (what makes sense to people and for people).

A competent designer will resolve each of these three constraints, but a design thinker will bring them into a harmonious balance. The popular Nintendo Wii is a good example of what happens when someone gets it right. For many years a veritable arms race of more sophisticated graphics and more expensive consoles has been driving the gaming industry. Nintendo realized that it would be possible to break out of this vicious circle—and create a more immersive experience—by using the new technology of gestural control. This meant less focus on the resolution of the screen graphics, which in turn led to a less expensive console and better margins on the product. The Wii strikes a perfect balance of desirability, feasibility, and viability. It has created a more engaging user experience and generated huge profits for Nintendo.

This pursuit of peaceful coexistence does not imply that all constraints are created equal; a given project may be driven disproportionately by technology, budget, or a volatile mix of human factors. Different types of organizations may push one or another of them to the fore. Nor is it a simple linear process. Design teams will cycle back through all three considerations throughout the life of a project, but the emphasis on fundamental human needs—as distinct from fleeting or artificially manipulated desires—is what drives design thinking to depart from the status quo.

Though this may sound self-evident, the reality is that most companies tend to approach new ideas quite differently. Quite reasonably, they are likely to start with the constraint of what will fit within the framework of the existing business model. Because business systems are designed for efficiency, new ideas will tend to be incremental, predictable, and all too easy for the competition to emulate. This explains the oppressive uniformity of so many products on the market today; have you walked through the housewares section of any department store lately, shopped for a printer, or almost gotten into the wrong car in a parking lot?

A second approach is the one commonly taken by engineering-driven companies looking for a technological breakthrough. In this scenario teams of researchers will discover a new way of doing something and only afterward will they think about how the technology might fit into an existing business system and create value. As Peter Drucker showed in his classic study Innovation and Entrepreneurship, reliance on technology is hugely risky. Relatively few technical innovations bring an immediate economic benefit that will justify the investments of time and resources they require. This may explain the steady decline of the large corporate R&D labs such as Xerox PARC and Bell Labs that were such powerful incubators in the 1960s and ’70s. Today, corporations instead attempt to narrow their innovation efforts to ideas that have more near-term business potential. They may be making a big mistake. By focusing their attention on near-term viability, they may be trading innovation for increment.

Finally, an organization may be driven by its estimation of basic human needs and desires. At its worst this may mean dreaming up alluring but essentially meaningless products destined for the local landfill—persuading people, in the blunt words of the design gadfly Victor Papanek, “to buy things they don’t need with money they don’t have to impress neighbors who don’t care.” Even when the goals are laudable, however—moving travelers safely through a security checkpoint or delivering clean water to rural communities in impoverished countries—the primary focus on one element of the triad of constraints, rather than the appropriate balance among all three, may undermine the sustainability of the overall program.

the project

Designers, then, have learned to excel at resolving one or another or even all three of these constraints. Design thinkers, by contrast, are learning to navigate between and among them in creative ways. They do so because they have shifted their thinking from problem to project.

The project is the vehicle that carries an idea from concept to reality. Unlike many other processes we are used to—from playing the piano to paying our bills—a design project is not open-ended and ongoing. It has a beginning, a middle, and an end, and it is precisely these restrictions that anchor it to the real world. That design thinking is expressed within the context of a project forces us to articulate a clear goal at the outset. It creates natural deadlines that impose discipline and give us an opportunity to review progress, make midcourse corrections, and redirect future activity. The clarity, direction, and limits of a well-defined project are vital to sustaining a high level of creative energy.

The “Innovate or Die Pedal-Powered Machine Contest” competition is a good example. Google teamed up with the bike company Specialized to create a design competition whose modest challenge was to use bicycle technology to change the world. The winning team—five committed designers and an extended family of enthusiastic supporters—was a late starter. In a few frenzied weeks of brainstorming and prototyping, the team was able to identify a pressing issue (1.1 billion people in developing countries do not have access to clean drinking water), explore a variety of alternative solutions (mobile or stationary? trailer or luggage rack?) and build a working prototype: The Aquaduct, a human-powered tricycle designed to filter drinking water while transporting it, is now traveling the world to help promote clean water innovation. It succeeded because of the inflexible constraints of technology (pedal power), budget ($0.00), and inflexible deadline. The experience of the Aquaduct team is the reverse of that found in most academic or corporate labs, where the objective may be to extend the life of a research project indefinitely and where the end of a project may mean nothing more than the funding has dried up.

the brief

The classic starting point of any project is the brief. Almost like a scientific hypothesis, the brief is a set of mental constraints that gives the project team a framework from which to begin, benchmarks by which they can measure progress, and a set of objectives to be realized: price point, available technology, market segment, and so on. The analogy goes even further. Just as a hypothesis is not the same as an algorithm, the project brief is not a set of instructions or an attempt to answer a question before it has been posed. Rather, a well-constructed brief will allow for serendipity, unpredictability, and the capricious whims of fate, for that is the creative realm from which breakthrough ideas emerge. If you already know what you are after, there is usually not much point in looking.

When I first started practicing as an industrial designer, the brief was handed to us in an envelope. It usually took the form of a highly constrained set of parameters that left us with little more to do than wrap a more or less attractive shell around a product whose basic concept had already been decided elsewhere. One of my first assignments was to design a new personal fax machine for a Danish electronics manufacturer. The technical aspects of the product took the form of a set of components that were being supplied by another company. Its commercial viability had been established by “management” and was geared to an existing market. Even its desirability had largely been predetermined by precedent, as everybody supposedly knew what a fax machine was supposed to look like. There was not a lot of room for maneuver, and I was left to try to make the machine stand out against those of other designers who were trying to do the same thing. It is no wonder that as more companies mastered the game, the competition among them became ever more intense. Nor have things changed much over the years. As one frustrated client recently lamented, “We are busting our ass for a few tenths of a percent of market share.” The erosion of margin and value is the inevitable result.

The proof of this can be found at any consumer electronics store, where, under the buzz of the fluorescent lights, thousands of products are arrayed on the shelves, clamoring for our attention and differentiated only by unnecessary if not unfathomable features. Gratuitous efforts at styling and assertive graphics and packaging may catch our eye but do little to enhance the experience of ownership and use. A design brief that is too abstract risks leaving the project team wandering about in a fog. One that starts from too ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Acknowledgments

- Ideo Project Case Studies

- Searchable Terms

- About the Author

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Change by Design by Tim Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.