- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

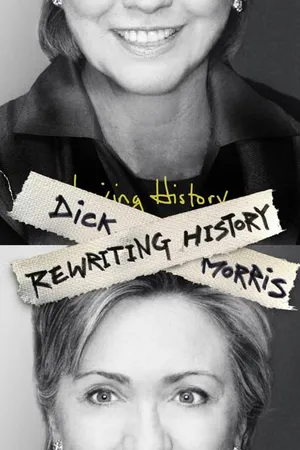

Rewriting History

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

6

Hiding Hillary:

The Material Girl

Future generations, when asked to free-associate the words “Clinton” and “scandal,” will probably summon up only the name “Lewinsky,” since that particular outrage led to the historic impeachment of a president. But the string of Hillary-generated scandals during the two Clinton administrations is stunningly impressive on its own.

The Whitewater investment; the firing of the White House Travel Office employees; the legal work for the Madison Bank; the hide-and-seek game with billing records; Vince Foster’s suicide; the misuse of FBI files; the source of payments to Webb Hubbell: Every one of these was a Hillary Clinton scandal. Even the wanton award of presidential pardons during the last days of the second term, which can be laid at Bill Clinton’s feet, weren’t his work alone: Among the recipients were her brothers’ clients, and some of her most ardent supporters.

Echoing through all of Hillary’s scandals—and distinguishing her troubles from the ones that nearly brought down her husband—is the sound of money. Bill had his scandals; Hillary had hers. George Stephanopoulos puts it this way in his memoir, All Too Human: “On [Whitewater], Clinton wasn’t commander in chief, just a husband beholden to his wife. Hillary was always the first to defend him on bimbo eruptions; now [on Hillary’s financial scandals] he had to do the same for her.”

At first, one is inclined to forgive Hillary’s financial misdeeds. After all, the amounts involved were not large and Bill and Hillary were not wealthy. Sandwiched in between the millionaire presidencies of Carter, Reagan, Bush, and Bush, the Clintons’ willingness to cut corners to salt away some savings is not necessarily grounds for outright condemnation.

But as the Clintons have amassed great wealth through their $18 million in book deals and Bill’s $10 million annual income, Hillary’s avarice has not abated. Her recent conduct suggests that her insensitivity to conflicts of interest and ethics rules, so much in evidence during her Arkansas days, has not changed. If anything, getting away with her past conduct seems to have emboldened her and desensitized her further to ethical lines.

And then there is Hillary’s book. If Living History is a window on the current evolution of Hillary’s ethical sensibilities, we are in for a very tough time if she ever becomes president. Hillary’s memoir is one continuous cover-up. Coming so gratuitously, almost four years after she left the White House, the cover-up is more disturbing than the scandals themselves. If Hillary truly believes what she writes about Whitewater, her commodities trading, the gifts, and such, she hasn’t learned a thing from her scandals—except to feel free to do it all again.

But what can she say? you may ask. She can’t very well reverse her statements over the decades and admit fault, can she?

Perhaps not. At the very least, though, she could indicate in general terms that she has learned from her experiences. But she doesn’t do that. Instead, to preserve HILLARY’s reputation, she reasserts her innocence at the top of her lungs, twisting and spinning the evidence to her advantage, determinedly absolving herself of any blame for anything.

Has she learned? Her account of each of the Hillary scandals in Living History suggests not.

It’s not terribly difficult to find the source of Hillary’s early financial scandals. From the start of the Clintons’ political career, Hillary claims that she was in a chronic state of financial insecurity, citing Bill’s $35,000 salary as governor. With everything in her husband’s life subordinated to the search for political power, according to her, it was her job—and her burden—to care for the Clinton family’s material needs.

In Living History, she repeats the family mantra: “Money means almost nothing to Bill Clinton. He is not opposed to making money or owning property; it has simply never been a priority. He’s happy when he has enough to buy books, watch movies, go out to dinner, and travel…. But I worried that because politics is an inherently unstable profession, we needed to build up a nest egg.”

Certainly $35,000 a year is no huge amount of money for a family of three, but it is misleading to compare Clinton’s salary as governor with a normal family paycheck. In the Arkansas Governor’s Mansion, the Clintons got free luxurious housing, furniture, meals, entertainment, transportation, babysitting, housekeeping, servants, state automobiles including fuel and insurance, chauffeurs, telephones, utilities, home repairs, health insurance, and homeowners’ insurance. In addition to a substantial entertainment budget, the governor also received a food allowance of more than $50,000 per year. A state credit card paid for travel. And none of these perks was taxable. Indeed, about the only things the Clintons actually had to pay for were books, clothing, and restaurant meals. And, of course, Hillary was making substantially more than $35,000 per year.

Add it up: Combining Bill’s salary with her own and throwing in the food budget, the governor’s entertainment allowance, and the various free services that came with the Mansion, the Clintons were quite well off—and carried very few financial obligations.

Yet Hillary felt broke—so much so that, early in her husband’s political career, the Clintons actually donated his used underwear to charity two separate years to garner the tax deduction.

It was this mind-set—this combination of perceived deprivation with a sense of entitlement—that led Hillary to take extraordinary risks at the start of Bill’s governorship to make money. Whitewater, the commodities trading, and her representation of the Madison Bank were all indications of Hillary’s increasingly insatiable desire for money, always masquerading as a need for security.

And there was nothing the Clintons wanted that they couldn’t get somebody to give them. When Chelsea was young, Hillary wanted to build a swimming pool for her on the grounds of the Mansion. Determined not to pay for it herself, and savvy enough not to use tax money, she arranged for private donors—the same type of fat cat friends who would dominate their White House years—to chip in for Chelsea’s pool.

When she told me of her plans, I was astounded. I felt that voters of that very poor state would see the pool as a symbol of pretentious wealth, and hold it against the Clintons at the next election. And what special favors would the donors have gotten for their money, other than the satisfaction of knowing that Hillary could do her laps? “How could you even think of that?” I asked. “You’ll get killed.”

“Well, it’s not really for us,” Hillary replied evenly. “The mansion is for all future governors of the state; they’ll be able to use it.”

“You’ll never be able to sell that argument,” I shot back. “The next time you fly over Little Rock, look down and count the number of swimming pools.” I asked her a pointed question: “The next time I do a poll, do you want me to ask whether people have swimming pools?”

That got her mad. “Why can’t we lead the lives of normal people? They can give their daughters swimming pools; why can’t we?”

“You can—you just have to pay for it,” I muttered as she stalked off.

After the election, when nobody was looking, the Clintons passed the hat and built the pool.

After years of making a lawyer’s six-figure salary, augmented by Bill’s income and the substantial perks of his office, Hillary still saw herself as a victim who had sacrificed a life of financial security. The fact that she lived in a mansion, surrounded by servants, chauffeurs, and other staff, seems not to have mattered.

At the other end of Bill’s political career, Hillary again took extraordinary risks to make money. The prospect of losing their government-subsidized luxurious lifestyle at last apparently drove Hillary into panic.

No surprise: It would take a truly extraordinary annual income to afford all the perks that came for free with the governorship of Arkansas, much less the presidency. Not only is the White House one of the most luxurious residences in the world, it offers a panoply of cooks, florists, beauty experts, drivers, cars, jets, helicopters, pilots, a vacation home at Camp David, a movie theater, pool, Jacuzzi, tennis court, hot tub, bowling alley, workout gym, the presidential box at the Kennedy Center, any painting at the National Gallery, elegant parties, the ability to invite any entertainer to perform anything at any time or any thinker to lecture: The Clintons had the world at their fingertips, a combination of privileges that’s not for sale at any price.

Faced with such a prodigious loss, at the end of her husband’s presidency Hillary reached out for money in every way she could. As with her Arkansas swimming pool, her solution was to solicit donations and gifts, taking huge political risks in the process.

Like bookends on Bill’s career, Hillary’s early greed in Whitewater and the commodities scandals, and her later greed in her huge book deal, call for gifts, and massive expropriation of furniture and other presents intended for the White House, triggered financial scandals that almost eradicated the good work her husband was trying to do in between.

In part, her latter-day avarice was disguised as a need to pay the massive legal bills she racked up defending her investments and Bill’s affairs. But one wonders if these legal bills are, in fact, ever going to be paid, or if they live on only as an excuse for Hillary’s acquisitiveness. The Clintons’ financial statements show continued debt for legal work, and few payments, despite their massive increases in income. They certainly are in no hurry to pay their lawyers, even as they rake in money hand over fist.

But mere acquisitiveness does not explain Hillary’s grasping. After all, the Clintons have shown an amazing ability to make money after their White House years. Bill’s book deal exceeds $10 million; hers was worth $8 million. Added to that, of course, is the former president’s almost unlimited ability to make money giving speeches. So why the grasping materialism and financial insecurity? Why take the kinds of risks she has?

Her sense of entitlement seems to have lingered long after any perceived financial need has been satisfied. By the end of her husband’s governorship, Hillary had come to embrace the idea that she was the one who gave up the beckoning blue chip legal career in downtown New York or Chicago, forsaking a cushy future for a life on the hustings in Arkansas. Repeated constantly, this account of history—revisionist though it may be—lay at the core of Hillary’s self-image.

And even at the Rose Law Firm in Little Rock, Hillary would point out, she could never make the kind of money she might have earned, because of the demands on her schedule—campaigning for her husband, heading the education task force, not to mention doing the job of Arkansas first lady. The leaves of absence and days away from the office made it impossible, even here, to realize her financial potential.

Her sense of deprivation and feeling of entitlement were interdependent. Was she not sacrificing everything to promote the public good through her husband’s election to public office? Had she not ventured into the heartland of deprivation—the 49th state—to bring progress and enlightenment? When she received material compensation, minimal as it was, was that not truly her just reward for such sacrifice?

It is likely that this sense of entitlement—not simple greed—was what led Hillary to take the risks she has to make money. For all of her vaunted discipline, this is the one area where her self-control goes on frequent, extended holiday. Her need to extract what she feels is just compensation for all her good work is one of the controlling forces in her life.

Such avarice is very dangerous in politics. Politicians and presidents are always being offered opportunities for personal enrichment. Some are ethical. Others are not. Anyone in public life needs sensitive antennae to tell which is which. Of our recent presidents, Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Ford, Carter, Reagan, and Bush Sr. clearly had an internal sense that made them back off when there was an ethical question. Johnson, Nixon, and Clinton did not.

Where is Hillary likely to fall on that list? Some might argue that Hillary’s newfound wealth will eliminate the temptation to cross the line. But Hillary’s refusal, in Living History, to admit that there even is a line—or that she has ever crossed it—gives one pause.

Conflicts of Interest

All elected officials, and the members of their immediate families, must make a special effort to resist propositions that entail conflicts of interest. If they wish to avoid reproach (and prison), they must be able to distinguish between an honest offer and an obvious bribe.

Thus far, Hillary has had three narrow escapes during her political career. Her dealings in commodities, the Whitewater real estate deal, and her legal representation of the Madison Bank at the Rose Law Firm all might easily have ruined her, and dragged Bill down as well. But her lengthy defense of her conduct in Living History reminds one of the Bourbon kings of France, of whom Talleyrand reportedly observed, “they learn nothing and they forget nothing.”

Scandal one, the commodities deal, raises serious questions. The only reason there was not a public inquiry about this issue was that the statute of limitations had lapsed by the time it was disclosed. And the timing was no accident: The Clintons had concealed Hillary’s trading profits by refusing to release their tax returns for the relevant years. By the time the media had unearthed the scandal, and pressure for a prosecution started to build, she was out of the woods.

In Living History, Hillary writes that her trading gains were “examined ad infinitum after Bill became President,” and that “the conclusion was that, like many investors at the time, I’d been fortunate.” But the only truly fortunate thing about the affair for the Clintons was the fact that Hillary managed to avoid any investigation. And just to be clear about the record: There was never any official investigation of her trades—only the work of enterprising investigative reporters. And thus there was no consensus “conclusion” that Hillary had just been lucky. That self-serving judgment was hers alone.

At around the time when her husband was being elected governor in 1978, Hillary began investing in commodities futures, under the guidance of her friend Jim Blair. There she parlayed a $1,000 investment into $100,000, making more than $6,000 on the first day.

Hillary’s advisors, attorney Jim Blair and broker Robert L. “Red” Bone, were especially knowledgeable about the flow of cattle onto the market: Blair was actively working as outside counsel for Tyson Foods, and Bone had also been associated with the company. By gauging and anticipating the ups and downs of the industry, they were able to give Hillary key guidance about her investments. And, as numerous reporters have since established in great detail, Hillary’s advisors were rewarded handsomely, in any number of ways, for the insights they shared with the first lady of Arkansas.

The Clintons knew that their commodities trades would sound alarm bells if they ever came to light. I know, because I watched them try to cover them up.

In 1982, as they were campaigning to win back the governorship, it became obvious to me that the Clintons were determined to hide something on their tax returns from public view. During the campaign, I urged them to release their income tax returns. It would be a good issue against Frank White, the Republican incumbent we had to beat. After all, I figured, Republicans often resist releasing their tax returns because of their business dealings. And I had totally bought into the myth that the Clintons were frugal, parsimonious people who cared little about money; what could they ever have done that might look embarrassing on a tax return?

So I asked Bill if he and Hillary would make their returns public, so that we could challenge White to reveal his.

“Of course,” Bill answered. “No problem.” But when the time came to release them, he turned finicky. “I’ll give them out for the last two years only,” he said.

“But what about the time you served in office as governor?” I asked.

“No,” he replied firmly. “I’m only releasing two years.”

“But if we are going to use the issue against Frank White, we need to release returns for the years you were governor. Otherwise, why should he have to?”

Bill glared at me; the discussion was clearly over. The Clintons released their tax returns, but not for 1978 or 1979. Why not? I wondered. When the scandal about Hillary’s winnings in cattle futures emerged, I had my answer: They were apparently anxious to hide her profits, lest there be questions about insider trading—or for a quid pro quo with Blair of state action in return for private benefit. After all, how did Hillary acquire the acumen to turn $1,000 into almost $100,000 in such a specialized market?

When the question was first raised in public, Hillary claimed that she had studied the Wall Street Journal to educate herself on the market. But then the Journal pulled the rug out from under her. Having examined its archives, James Stewart reported in Blood Sport that “It was obvious that they would have been of scant value to any trader. Ultimately…the first lady backed off the claim, acknowledging that it was Blair who had guided her trading.”

Was Hillary’s trading based on insider information and hence illegal? The difference between legal and illegal inputs in commodities trading, it turns out, is quite a hair to split. But, as judges are fond of saying, we do not have to “reach” that issue. The real question is, why did he share it with Hillary Clinton? Hillary acts as if friendship were the sole reason. But here’s what Blair and Tyson Foods, his client, got from the Clintons over the years:

- The New York Times reported that “Tyson benefited from a variety of state actions, including $9 million in government loans, the placement of company executives on important state boards and favorable decisions on environmental issues.”

- Blair was appointed chairman of the board of the University of Arkansas by Governor Clinton.

- President Clinton named Blair’s wife, Diane, to the board of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

- As Arkansas attorney general, Clinton intervened in a lawsuit that helped Tyson Foods.

- Governor Clinton reappointed a Tyson veterinarian to the Livestock and Poultry Commission, which regulated Tyson Foods.

- When a Tyson plant leaked waste into a creek that eventually polluted the water supply of the town of Dry Creek, Arkansas, the state never enforced an order making the company treat its wastes. After nearby families began to get sick, Clinton had to declare the town a disaster area.

- According to the Times, Ron Brown, Clinton’s secretary of commerce, “reversed course and instituted rules that would allow Arctic Alaska (a Tyson subsidiary) and other big trawlers to dominate the nation’s $100 million whiting catch.”

Although James Blair was never charg...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Chapter 01

- Chapter 02

- Chapter 03

- Chapter 04

- Chapter 05

- Chapter 06

- Chapter 07

- Chapter 08

- Chapter 09

- Notes

- Acknowledgements

- Searchable Terms

- About the Author

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Rewriting History by Dick Morris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Biografías históricas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.