- 576 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

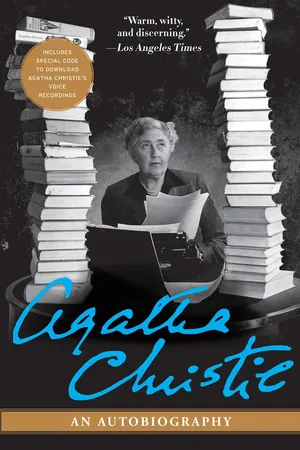

An Autobiography

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

ASHFIELD

O! ma chère maison; mon nid, mon gîte

Le passé Vhabite…O ma chère maison

I

One of the luckiest things that can happen to you in life is to have a happy childhood. I had a very happy childhood. I had a home and a garden that I loved; a wise and patient Nanny; as father and mother two people who loved each other dearly and made a success of their marriage and of parenthood.

Looking back I feel that our house was truly a happy house. That was largely due to my father, for my father was a very agreeable man. The quality of agreeableness Is not much stressed nowadays. People tend to ask if a man is clever, industrious, if he contributes to the well-being of the community, if he ‘counts’ in the scheme of things. But Charles Dickens puts the matter delightfully in David Copperfield:

‘Is your brother an agreeable man, Peggotty?’ I enquired cautiously.

‘Oh what an agreeable man he is!’ exclaimed Peggotty.

Ask yourself that question about most of your friends and acquaintances, and you will perhaps be surprised at how seldom your answer will be the same as Peggotty’s.

By modern standards my father would probably not be approved of.

He was a lazy man. It was the days of independent incomes, and if you had an independent income you didn’t work. You weren’t expected to. I strongly suspect that my father would not have been particularly good at working anyway.

He left our house in Torquay every morning and went to his club.

He returned, in a cab, for lunch, and in the afternoon went back to the club, played whist all afternoon, and returned to the house in time to dress for dinner. During the season, he spent his days at the Cricket Club, of which he was President. He also occasionally got up amateur theatricals. He had an enormous number of friends and loved entertaining them. There was one big dinner party at our home every week, and he and my mother went out to dinner usually another two or three times a week.

It was only later that I realized what a much loved man he was. After his death, letters came from all over the world. And locally tradesmen, cabmen, old employees–again and again some old man would come up to me and say: ‘Ah! I remember Mr Miller well. I’ll never forget him.

Not many like him nowadays.’

Yet he had no outstanding characteristics. He was not particularly intelligent. I think that he had a simple and loving heart, and he really cared for his fellow men. He had a great sense of humour and he easily made people laugh. There was no meanness in him, no jealousy, and he was almost fantastically generous. And he had a natural happiness and serenity.

My mother was entirely different. She was an enigmatic and arresting personality–more forceful than my father–startlingly original in her ideas, shy and miserably diffident about herself, and at bottom, I think, with a natural melancholy.

Servants and children were devoted to her, and her lightest word was always promptly obeyed. She would have made a first class educator.

Anything she told you immediately became exciting and significant.

Sameness bored her and she would jump from one subject to another in a way that sometimes made her conversation bewildering. As my father used to tell her, she had no sense of humour. To that accusation she would protest in an injured voice: ‘Just because I don’t think certain stories of yours are funny, Fred…’ and my father would roar with laughter.

She was about ten years younger than my father and she had loved him devotedly ever since she was a child often. All the time that he was a gay young man, flitting about between New York and the South of France, my mother, a shy quiet girl, sat at home, thinking about him, writing an occasional poem in her ‘album,’ embroidering a pocket-book for him.

That pocket-book, incidentally, my father kept all his life.

A typically Victorian romance, but with a wealth of deep feeling behind it.

I am interested in my parents, not only because they were my parents, but because they achieved that very rare production, a happy marriage.

Up to date I have only seen four completely successful marriages. Is there a formula for success? I can hardly think so. Of my four examples, one was of a girl of seventeen to a man over fifteen years her senior. He had protested she could not know her mind. She replied that she knew it perfectly and had determined to marry him some three years back!

Their married life was further complicated by having first one and then the other mother-in-law living with them-enough to wreck most alliances. The wife is calm with a quality of deep intensity. She reminds me a little of my mother without having her brilliance and intellectual interests. They have three children, all now long out in the world. Their partnership has lasted well over thirty years and they are still devoted.

Another was that of a young man to a woman fifteen years older than himself–a widow. She refused him for many years, at last accepted him, and they lived happily until her death 35 years later.

My mother Clara Boehmer went through unhappiness as a child.

Her father, an officer in the Argyll Highlanders, was thrown from his horse and fatally injured, and my grandmother was left, a young and lovely widow with four children, at the age of 27 with nothing but her widow’s pension. It was then that her elder sister, who had recently married a rich American as his second wife, wrote to her offering to adopt one of the children and bring it up as her own.

To the anxious young widow, working desperately with her needle to support and educate four children, the offer was not to be refused. Of the three boys and one girl, she selected the girl; either because it seemed to her that boys could make their way in the world while a girl needed the advantages of easy living, or because, as my mother always believed, she cared for the boys more. My mother left Jersey and came to the North of England to a strange home. I think the resentment she felt, the deep hurt at being unwanted, coloured her attitude to life. It made her distrustful of herself and suspicious of people’s affection. Her aunt was a kindly woman, good-humoured and generous, but she was imperceptive of a child’s feelings. My mother had all the so-called advantages of a comfortable home and a good education–what she lost and what nothing could replace was the carefree life with her brothers in her own home.

Quite often I have seen in correspondence columns enquiries from anxious parents asking if they ought to let a child go to others because of ‘the advantages she will have which I cannot provide–such as a first-class education’. I always long to cry out: Don’t let the child go. Her own home, her own people, love, and the security of belonging–what does the best education in the world mean against that?

My mother was deeply miserable in her new life. She cried herself to sleep every night, grew thin and pale, and at last became so ill that her aunt called in a doctor. He was an elderly, experienced man, and after talking to the little girl he went to her aunt and said: ‘The child’s homesick.’

Her aunt was astonished and unbelieving. ‘Oh no,’ she said. ‘That couldn’t possibly be so. Clara’s a good quiet child, she never gives any trouble, and she’s quite happy.’ But the old doctor went back to the child and talked to her again. She had brothers, hadn’t she? How many?

What were their names? And presently the child broke down in a storm of weeping, and the whole story came out.

Bringing out the trouble eased the strain, but the feeling always remained of ‘not being wanted’. I think she held it against my grandmother until her dying day. She became very attached to her American ‘uncle’. He was a sick man by then, but he was fond of quiet little Clara and she used to come and read to him from her favourite book, The King of the Golden River. But the real solace in her life were the periodical visits of her aunt’s stepson–Fred Miller–her so-called ‘Cousin Fred’.

He was then about twenty and he was always extra kind to his little ‘cousin’. One day, when she was about eleven, he said to his stepmother:

‘What lovely eyes Clara has got!’

Clara, who had always thought of herself as terribly plain, went upstairs and peered at herself in her aunt’s large dressing-table mirror.

Perhaps her eyes were rather nice…She felt immeasurably cheered.

From then on, her heart was given irrevocably to Fred.

Over in America an old family friend said to the gay young man, ‘Freddie, one day you will marry that little English cousin of yours.’

Astonished, he replied, ‘Clara? She’s only a child.’

But he always had a special feeling for the adoring child. He kept her childish letters and the poems she wrote him, and after a long series of flirtations with social beauties and witty girls in New York (among them Jenny Jerome, afterwards Lady Randolph Churchill) he went home to England to ask the quiet little cousin to be his wife.

It is typical of my mother that she refused him firmly.

‘Why?’ I once asked her.

‘Because I was dumpy,’ she replied.

An extraordinary but, to her, quite valid reason.

My father was not to be gainsaid. He came a second time, and on this occasion my mother overcame her misgivings and rather dubiously agreed to marry him, though full of misgivings that he would be ‘disappointed in her’.

So they were married, and the portrait that I have of her in her wedding dress shows a lovely serious face with dark hair and big hazel eyes.

Before my sister was born they went to Torquay, then a fashionable winter resort enjoying the prestige later accorded to the Riviera, and took furnished rooms there. My father was enchanted with Torquay. He loved the sea. He had several friends living there, and others, Americans, who came for the winter. My sister Madge was born in Torquay, and shortly after that my father and mother left for America, which at that time they expected to be their permanent home. My father’s grandparents were still living, and after his own mother’s death in Florida he had been brought up by them in the quiet of the New England countryside.

He was very attached to them and they were keen to see his wife and baby daughter. My brother was born whilst they were in America. Some time after that my father decided to return to England. No sooner had he arrived than business troubles recalled him to New York. He suggested to my mother that she should take a furnished house in Torquay and settle there until he could return.

My mother accordingly went to look at furnished houses in Torquay.

She returned with the triumphant announcement: ‘Fred; I’ve bought a house!’

My father almost fell over backwards. He still expected to live in America.

‘But why did you do that?’ he asked.

‘Because I liked it,’ explained my mother.

She has seen, it appeared, about 35 houses, but only one did she fancy, and that house was for sale only–its owners did not want to let. Sc my mother, who had been left £2000 by my aunt’s husband, had appealed to my aunt, who was her trustee, and they had forthwith bought the house.

‘But we’ll only be there for a year,’ groaned my father, ‘at most.’

My mother, whom we always claimed was clairvoyant, replied that they could always sell it again. Perhaps she saw dimly her family living in that house for many years ahead.

‘I loved the house as soon as I got into it,’ she insisted. ‘It’s got a wonderfully peaceful atmosphere.’

The house was owned by some people called Brown who were Quakers, and when my mother, hesitatingly, condoled with Mrs Brown on having to leave the house they had lived in so many years, the old lady said gently:

‘I am happy to think of thee and thy children living here, my dear.’

It was, my mother said, like a blessing.

Truly I believe there was a blessing upon the house. It was an ordinary enough villa, not in the fashionable part of Torquay–the Warberrys or the Lincombes–but at the other end of the town the older part of Tor Mohun. At that time the road in which it was situated led almost at once into rich Devon country, with lanes and fields. The name of the house was Ashfield and it has been my home, off and on, nearly all my life.

For my father did not, after all, make his home in America. He liked Torquay so much that he decided not to leave it. He settled down to his club and his whist and his friends. My mother hated living near the sea, disliked all social gatherings and was unable to play any game of cards.

But she lived happily in Ashfield, and gave large dinner parties, attended social functions, and on quiet evenings at home would ask my father with hungry impatience for local drama and what had happened at the club today.

‘Nothing,’ my father would reply happily.

‘But surely, Fred, someone must have said something interesting?’

My father obligingly racks his brains, but nothing comes. He says that M—is still too mean to buy a morning paper and comes down to the club, reads the news there, and then insists on retailing it to the other members. ‘I say, you fellows, have you seen that on the North West Frontier…’ etc. Everyone is deeply annoyed, since M—is one of the richest members.

My mother, who has heard all this before, is not satisfied. My father relapses into quiet contentment. He leans back in his chair, stretches out his legs to the fire and gently scratches his head (a forbidden pastime).

‘What are you thinking about, Fred?’ demands my mother.

‘Nothing,’ my father replies with perfect truth.

‘You can’t be thinking about nothing?

Again and again that statement baffles my mother. To her it is unthinkable.

Through her own brain thoughts dart with the swiftness of swallows in flight. Far from thinking of nothing, she is usually thinking of three things at once.

As I was to realise many years later, my mother’s ideas were always slightly at variance with reality. She saw the universe as more brightly coloured than it was, people as better or worse than they were. Perhaps because in the years of her childhood she had been quiet, restrained, with her emotions kept well below the surface, she tended to see the world in terms of drama that came near, sometimes, to melodrama. Her creative imagination was so strong that it could never see things as drab or ordinary. She had, too, curious flashes of intuition–of knowing suddenly what other people were thinking. When my brother was a young man in the Army and had got into monetary difficulties which he did not mean to divulge to his parents, she startled him one evening by looking across at him as he sat frowning and worrying. ‘Why, Monty,’ she said, ‘you’ve been to moneylenders. Have you been raising money on your grandfather’s will? You shouldn’t do that. It’s better to go to your father and tell him about it.’

Her faculty for doing that sort of thing was always surprising her family. My sister said once: ‘Anything I don’t want mother to know, I don’t even think of, if she’s in the room.’

II

Difficult to know what one’s first memory is. I remember distinctly my third birthday. The sense of my own importance surges up in me. We are having tea in the garden–in the part of the garden where, later, a hammock swings between two trees.

There is a tea-table and it is covered with cakes, with my birthday cake, all sugar icing and with candles in the middle of it. Three candles. And then the exciting occurrence–a tiny red spider, so small that I can hardly see it, runs across the white cloth. And my mother says: ‘It’s a lucky spider, Agatha, a lucky spider for your birthday…’ And then the memory fades, except for a fragmentary reminiscence of an interminable argument sustained by my brother as to how many eclairs he shall be allowed to eat.

The lovely, safe, yet exciting world of childhood. Perhaps the most absorbing thing in mine is the garden. The garden was to mean more and more to me, year after year. I was to know every tree in it, and attach a special meaning to each tree. From a very early time, it was divided in my mind into three distinct parts.

There was the kitchen garden, bounded by a high wall which abutted on the road. This was uninteresting to me except as a provider of raspberries and green apples, both of which I ate in large quantities. It was the kitchen garden but nothing else. It offered no possibilities of enchantment.

Then came the garden proper–a stretch of lawn running downhill, and studded with certain interesting entities. The ilex, the cedar, the Wellingtonia (excitingly tall). Two fir-trees, associated for some reason not now clear with my brother and sister. Monty’s tree you could climb (that is to say hoist yourself gingerly up three branches). Madge’s tree, when you had burrowed cautiously into it, had a seat, an invitingly curved bough, where you could sit and look out unseen on the outside world. Then there was what I called...

Table of contents

- Preface

- Foreword

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Part IV

- Part V

- Part VI

- Part VII

- Part VIII

- Part IX

- Part X

- Part XI

- Epilogue

- Searchable Terms

- About the Author

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access An Autobiography by Agatha Christie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.