eBook - ePub

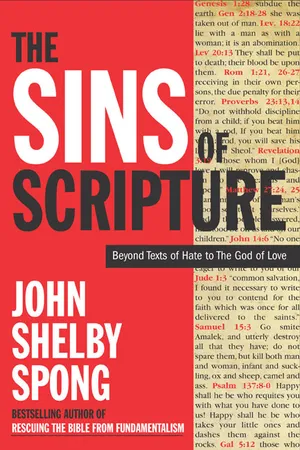

The Sins of Scripture

Exposing the Bible's Texts of Hate to Reveal the God of Love

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the history of the Western World, the Bible has been a perpetual source of inspiration and guidance for countless Christians. However, this Bible has also left a trail of pain. Controversial bishop and champion of liberal Christianity John Shelby Spong explores those passages that have been used to justify oppression, violence, discrimination against women and homosexuals, and murder. As he exposes and challenges what he calls the "terrible texts of the Bible," laying bare the evil done in the name of God, he also seeks to redeem them, hoping to recover their ultimate depth and purpose.

As Spong battles against the way the Bible has been used throughout history, he provides a new framework for interpretation, explaining how the Bible's overall good news overcomes these "terrible texts," and delivering a fresh, inspiring message of how Christians can use the Bible today. John Shelby Spong was the Episcopal Bishop of Newark before his retirement in 2000. As a visiting lecturer at Harvard and at universities and churches throughout North America and the English-speaking world, he is one of the leading spokespersons for liberal Christianity. His books include A New Christianity for a New World, Rescuing the Bible from Fundamentalism, Resurrection: Myth or Reality?, Why Christianity Must Change or Die, and his autobiography, Here I Stand. "A valuable modernist manifesto for progressive readers seeking a response to the conservative theology dominating the news these days." -Boston GlobeFrequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Sins of Scripture by John Shelby Spong in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Jewish History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION 1

THE WORD OF GOD

1

WHY THIS BOOK, THIS THEME, THIS AUTHOR

The Bible is a subject of interpretation: there is no doctrine, no prophet, no priest, no power, which has not claimed biblical sanctions for itself.

Paul Tillich1

It is a mysterious book, this Bible. It possesses a strange kind of power. It has been the best-selling book in the world every year since printing began. It comes as no surprise to recall that when the Gutenberg press was invented, it was the Bible that first bore the imprint of its metal letters. There is hardly a language or a dialect in the world today into which the words of the Bible have not been translated. Its stories, its words and its phrases have permeated our culture, infiltrating even our subconscious minds. One thinks of motion picture titles that are direct quotations from scripture: Lilies of the Field (Matt. 6:28), a 1968 film that earned Sidney Poitier an Oscar for best actor; Inherit the Wind (Prov. 11:29), the classic film about the Scopes trial set in the Tennessee of 1925 with Spencer Tracy starring as Clarence Darrow and Fredric March as William Jennings Bryan; and Through a Glass Darkly (1 Cor. 13:12), an Ingmar Bergman masterpiece. Beyond these titles there have also been motion pictures dramatizing biblical epics, frequently in overblown Hollywood style: The Ten Commandments, Samson and Delilah, David and Bathsheba, Barabbas and in more recent days The Passion of the Christ.

Beyond overt references, biblical allusions are constantly used in literature. Without some knowledge of the sacred text, many expressions in our language would be meaningless. John Steinbeck’s novel East of Eden comes to mind, along with Exodus by Leon Uris, The Green Pastures by Marc Connelly and The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse by Vicente Blasco Ibanez, which became a motion picture directed by Vincent Minnelli.

The words of the Bible enrich our everyday speech whether we are aware of it or not: “for crying out loud,” which refers to Jesus on the cross; “land of Goshen,” a reference to that section of Egypt which housed the Jewish slaves; “sour grapes,” a phrase which derives from Jeremiah 31:39 that is widely used to explain behavior; and “the olive branch” as a sign of peace, which comes from the story of Noah. Far more than anyone realizes, all of Western life has been deeply shaped by the fact that the content of this Bible has washed over our civilization for more than two thousand years. Biblical concepts are so deeply written into our individual and corporate psyches that even nonbelievers accept them as both inevitable and simply a part of the way life is.

In the history of the Western world, however, this Bible has also left a trail of pain, horror, blood and death that is undeniable. Yet this fact is not often allowed to rise to consciousness. Biblical words have been used not only to kill, but even to justify that killing. This book has been relentlessly employed by those who say they believe it to be God’s Word, to oppress others who have been, according to these believers, defined in the “hallowed” pages of this text as somehow subhuman. Quotations from the Bible have been cited to bless the bloodiest of wars. People committed to the Bible have not refrained from using the cruelest forms of torture on those whom they believe to have been revealed as the enemies of God in these “sacred” scriptures. A museum display that premiered in Florence in 1983, and later traveled to the San Diego Museum of Man in 2003, featured the instruments used on heretics by Christians during the Inquisition. They included stretching machines designed literally to pull a person apart, iron collars with spikes to penetrate the throat, and instruments that were used to impale the victims. The Bible has been quoted throughout Western history to justify the violence done to racial minorities, women, Jews and homosexuals. It might be difficult for some Christians to understand, but it is not difficult to document the terror enacted by believers in the name of the Bible.

How is it possible, we must ultimately wonder, that this book, which is almost universally revered in Western religious circles, could also be the source of so much evil? Can that use of the Bible be turned around and brought to an end? Can the Bible once again be viewed as a source—even an ultimate source—of life? Or is it too late and the Bible too stained? Those are the themes I will seek to address in this volume.

My qualifications for telling this story are twofold: first, I have had a lifetime love affair with this Bible; and second, I am a church insider, who yearns to see the church become what it was meant to be. I will not give up on the Bible or the church easily, but I will insist that the Bible be looked at honestly in the light of the best scholarship available and that the church consciously own its historical destructiveness.

I do not know exactly when my love affair with the Bible began. Perhaps its first seeds were planted when I was a child and began to notice that the family Bible was displayed prominently on the coffee table in our modest living room. I do not recall my parents ever reading it, but there was no question that it was revered. I did see it used to record the family’s history in a special section that bore titles like “Births,” “Deaths” and “Marriages.” Nothing was ever to be placed on top of that holy volume—not another book, not a glass or a bottle, not even a piece of mail. This sanctified book could brook no cover, nor could it be seen as secondary in any way to any other entity. This attitude was certainly encouraged and my passion for this book was enhanced by the schools, both weekday and Sunday, that I attended eagerly as a young pupil.

Yes, as hard as it is for citizens of the twenty-first century to imagine this scenario, stories from the Bible were read or told to the children of my generation in both church school and public school with regularity. I suspect that if one had to compare the two places, it would be the public schools in my region that were even more fervent about revering the Bible than were my church’s Sunday school sessions. There is a sense in which the public schools in the southern part of the United States where I grew up were, in an earlier day, little more than Protestant parochial schools. Every public school day in my childhood began with both a Bible story and a prayer, most often the Lord’s Prayer, led by a teacher. I suppose that a sense of awe was communicated to me during this daily opening exercise, for inattentiveness was said to be “rude to God.” Following these opening religious rituals we recited the pledge of allegiance to the flag. Devotion to both God and my nation were regularly placed side by side with God always coming first. Indeed, my nation was said to be the instrument through which God worked in this world. These sentiments were not far from a concept of America being a new divinely chosen people.

The intensity of these public school religious exercises depended to some degree on the piety of the particular teacher. To this day I can bring to mind indelible memories of the public school teacher I had when I was ten years old. Her name was Mrs. Owens—Claire Yates Owens, to be specific. She started our class each day by reading a chapter from a children’s Bible storybook. These tales were not unlike radio soap operas in that they left the listener hanging in anticipation of what the next episode would reveal. Most of us could not wait to see what was going to happen to Moses in the midst of the Red Sea or to Joshua in the battle of Jericho. We hung on Paul’s every adventure and reveled in his most recent shipwreck or snakebite. The stories from this book were so natural to our lives and so deeply a part of our culture that none of us could imagine a time when the Supreme Court of our land would declare this activity to be unconstitutional. Mrs. Owens even required us to memorize the Ten Commandments in the long form directly from the book of Exodus. None of those Reader’s Digest shortened versions would do for her! That meant we had to repeat all of those intimate details found in the second commandment about how the “sins of the fathers would be visited upon the children to the third and fourth generation.” We all hoped our great-grandparents had been virtuous people lest we be forced to pay the price of their evildoing. There was also that long list of both people and creatures that the fourth commandment ordered to refrain from labor on the Sabbath. Memorizing these convoluted and intricate passages was worth the reward of special public commendation that Mrs. Owens both promised and delivered. If one wanted extra credit in this class, or at least the satisfaction of impressing our demanding teacher and being recognized as extraordinary by our peers, we were encouraged, although not required, to memorize in order all of the sixty-six books in our King James Protestant version of the scriptures. I passed that test then and can still recite them to this day.

Yet from even that early date as I perused the sacred text I would come across a narrative from time to time that was brutal or insensitive. Still, no matter what I discovered on those hallowed pages, the fact that it was in the Bible surrounded each passage with an aura that was designed to reaffirm my trust in the ultimate goodness of all its words. I recall even in this early part of my life asking questions about the Bible. Those questions, however, were still relatively safe. “Why,” I wondered, “was the language of the Bible different from all of the other books we read?” By “language” I really meant “English,” since that was the only language I knew. “Why was this book filled with words like ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ or verbs like ‘shalt’ and ‘beseecheth’?” “Why was it that in the Bible when Jesus wanted to make an important pronouncement, he would introduce it by saying: ‘Verily, verily, I say unto you…’?” I could not imagine anyone else saying such stilted, silly-sounding words in any other setting. These unusual words and phrases communicated to me that this book was somehow profoundly different from all others. I had not yet confronted the Elizabethan English of William Shakespeare and knew nothing about how my native tongue had developed. I suppose my classmates and I made lots of unconscious assumptions. I know I identified this holy-sounding language of the Bible with the language of God. Perhaps, I reasoned, God was so old that the divine language was the classical English of long ago. The idea that God or Jesus had spoken anything other than English had not yet dawned on me. I was told this book revealed God’s language and that assumption was reinforced in my mind every time someone referred to this book as the “Word of God.”

There were other issues about this book that were different, but I did not yet even wonder, much less ask, about them. For instance, why was this book typically printed with two columns of type on each page? Sometimes these columns were separated by a simple line, but on other occasions by a narrow center section that ran down the entire page and was filled with small, italicized type and other strange hieroglyphics. No other books that I knew of except dictionaries and encyclopedias were printed this way. This was a particularly interesting insight when it finally dawned on me that no one was ever supposed to sit down and read a dictionary or an encyclopedia. These were, rather, resource books to which one turned to get specific answers to particular queries. Was the Bible printed this way to encourage me to think of it as a kind of holy dictionary or sacred encyclopedia that possessed all the answers to all the questions that I might ever ask? Even now when I raise these possibilities they sound a bit sinister, so you may be sure they were not allowed to enter my mind as a child. But I still wonder if this was a conscious or an unconscious decision. Did that layout reflect the position of the hierarchy in the Western Catholic tradition? Was that part of the church leaders’ campaign to keep the Bible from being read, at least not by the uneducated masses? Does that printed style itself reflect their need to guard the Bible’s secrets in order to protect their authority? I suspect it does and that even then I was being trained, quite unconsciously, to view the Bible as a resource book to which I would turn only to get the final answers to my questions, and thus to accustom myself to think of the Bible as an ultimate, undebatable authority from which there was no further appeal in the quest for truth. That is certainly consistent with the way the Bible has been used in Western history. Whatever the motives were which produced these realities, conscious or unconscious, they surely worked on me. The Bible was different from every other book in its ultimate power.

I approached this book and its holiness rather tangentially as a child. Children’s Bible storybooks were my absolute favorites. The more graphic the pictures, the better I liked them. I am sure that both this affinity and my affection for Bible stories were noticed and encouraged by my mother, for on the Christmas following my twelfth birthday—perhaps not coincidentally it was also the Christmas following the death of my father—I received as my primary present, my “Santa gift” as our family called it, my very own personal copy of the Holy Bible.

I was thrilled with this gift. Nothing could have pleased me more. This particular Bible was large in size with gilt-edged, tissue-thin pages and a cross on its leather cover. That cover was both thin and pliable, so that my Bible could be held in one hand with its cover and pages flopping down on each side of the hand of the holder just as they did when preachers held the Bible while expounding on its various texts at revivals and from church pulpits. This Bible also had a concordance in the back that would guide me to places where particular words or characters might be located. It possessed all kinds of introductory material and page after page of notes. Included in its appendix were colored maps of the Holy Land. On one of those maps I could see visually the boundaries of each of the twelve tribes of Israel and could even locate the little-known lands of Naphtali, Dan and Benjamin. On another map I could follow in minute detail both the journey of Jesus from Galilee to Jerusalem and the travels of Paul, first into the desert of Arabia and later across the lands contiguous to the Mediterranean Sea. Most special of all to me was the fact that this Bible was a “red letter edition,” in which all the words believed to have been spoken by Jesus were printed in red, so that these words literally leaped off the pages in importance. I am sure that part of my excitement over this Christmas gift was contained in the realization that it was in some sense an acknowledgment on my mother’s part that I was growing up and that the time had come for me to give up childish things like children’s Bible storybooks and to start feeding my soul on the “red meat” of the Bible’s own words. Whatever motives were operating in my psyche or even my mother’s psyche, I took to this book like a duck to water and immediately began to immerse myself in its content. I cannot imagine my grandchildren today responding in a similar fashion.

When the excitement of Christmas Day was over that year, I placed my treasured new gift on the table beside my bed and began that night a regular practice of reading it, day after day, week after week, month after month and year after year. That was more than sixty years ago. There have been few days in my life since that Christmas that I have not intentionally and intensely read and studied these words. I suppose I have worked through this sacred text from cover to cover some twenty to twenty-five times. Some individual books, like the four gospels, the Acts of the Apostles and Genesis, I have read many more times than that. Because I loved this book so much and because I read it so carefully, I could not fail to notice its gory passages that did not jibe with what I had been told about either God or religion. I met in its pages things that were disturbing, malevolent and evil. That was how the dark side of the Bible first began to dawn on my consciousness.

Looking back, I believe now that these insights would have come to me even sooner had I not been what the Bible seems to regard as a privileged person. I do not refer to my social or economic status, which was modest to say the least, but to the fact that I was white, male, heterosexual and Christian. The Bible affirmed, or so I was taught, the value in each of these privileged designations. It was clearly preferable to be white than to be a person of color; male, in whom the image of God was clear, rather than female; heterosexual and therefore “normal” rather than homosexual and therefore “abnormal”; and Christian, which was, of course, the only true religion. I grew up secure in each of these definitions.

I hope these brief autobiographical comments will make it clear that I do not come to this biblical interpretive task as an enemy of Christianity. I am a Christian, a deeply committed, believing Christian. I am not even a disillusioned former Christian, as some of my biblical scholar friends now identify themselves. I recognize that the Christian faith has traditionally claimed that its beliefs and practices are based on and supported by the Bible. I understand the centrality of this book. I write as one whose entire professional life has been lived in the service of that Christian church with which I am still joyfully identified. I was ordained a priest in the Episcopal Church at age twenty-four and elected one of its bishops at age forty-four. I am a person who organized my priestly vocation after the analogy of a seminary professor, by interpreting my ordained role to be that of a teacher and the church primarily as a teaching center. The textbook that I taught my congregations Sunday after Sunday and year after year was the Bible. At diocesan centers, first across the South and later across the nation, I led conferences on the Bible. In parishes where I was the rector I initiated adult Bible classes for an hour prior to the Sunday worship service each week. The content I presented each Sunday using a lecture format would not have been dissimilar from that found in any seminary or theological college. I believed that my parishioners could learn everything that I had been taught. I regarded those classes as my highest priority and prepared for them more rigorously than I prepared for anything else I did. If the people in my congregation did not want to drink from the fountain that I was offering, there were plenty of other churches available from which they could choose. I never believed in tailoring the class to the security level of its members by hedging the truth. My aim was to challenge people with the insights of the scholars and to make contemporary biblical thinking available to them.

I would normally spend an entire year on a single book of the Bible, choosing a commentary to guide my thinking from among the world’s great biblical scholars. I would work on that book of the Bible and that commentary week after week until both became part of what I know and who I am.2 It was my ambition to work through the entire Bible with my congregations in the course of my ministry. I did not plan to skip even Obadiah or Nahum and figured I could complete this study in the years of my priestly career.

My election as a bishop tempered that ambition but did not diminish my zest for teaching. Like my great mentor John A. T. Robinson in England, I interpreted the office of bishop as a teaching and writing office. The result of this commitment was that I both know and love the Bible deeply. I also recognize where its warts are.

I know what parts of it have been used to undergird prejudices and to mask violence. I have discovered that there is a strange ability among believers not to see the negative side of their religious symbols. It did not take a geniu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Section 1: The Word Of God

- Section 2: The Bible And The Environment

- Section 3: The Bible And Women

- Section 4: The Bible And Homosexuality

- Section 5: The Bible And Children

- Section 6: The Bible And Anti-Semitism

- Section 7: The Bible And Certainty

- Section 8: Reading Scripture As Epic History

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Scripture Index

- About the Author

- Other Books By John Shelby Spong

- Copyright

- About the Publisher