- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

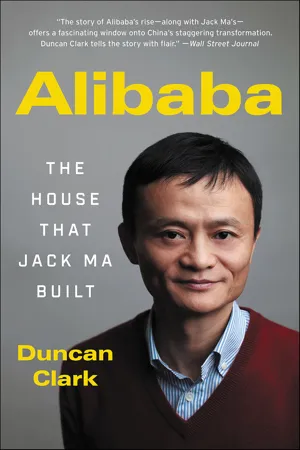

"The story of Alibaba's rise—along with Jack Ma's—offers a fascinating window onto China's staggering transformation." —

The Wall Street Journal

In just a decade and half Jack Ma, a man who rose from humble beginnings and started his career as an English teacher, founded and built Alibaba into the second largest Internet company in the world. The company's $25 billion IPO in 2014 was the world's largest, valuing the company more than Facebook or Coca Cola. Alibaba today runs the e-commerce services that hundreds of millions of Chinese consumers depend on every day, providing employment and income for tens of millions more. A Rockefeller of his age, Jack has become an icon for the country's booming private sector, and as the face of the new, consumerist China is courted by heads of state and CEOs from around the world.

Granted unprecedented access to a wealth of new material including exclusive interviews, Clark draws on his own first-hand experience of key figures integral to Alibaba's rise to create an authoritative, compelling narrative account of how Alibaba and its charismatic creator have transformed the way that Chinese exercise their new found economic freedom, inspiring entrepreneurs around the world and infuriating others, turning the tables on the Silicon Valley giants who have tried to stand in his way.

An expert insider with unrivaled connections, Clark has a deep understanding of Chinese business mindset. He illuminates an unlikely corporate titan as never before, and examines the key role his company has played in transforming China while increasing its power and presence worldwide.

"A must-read for anyone hoping to navigate China's new economy." — Financial Times

In just a decade and half Jack Ma, a man who rose from humble beginnings and started his career as an English teacher, founded and built Alibaba into the second largest Internet company in the world. The company's $25 billion IPO in 2014 was the world's largest, valuing the company more than Facebook or Coca Cola. Alibaba today runs the e-commerce services that hundreds of millions of Chinese consumers depend on every day, providing employment and income for tens of millions more. A Rockefeller of his age, Jack has become an icon for the country's booming private sector, and as the face of the new, consumerist China is courted by heads of state and CEOs from around the world.

Granted unprecedented access to a wealth of new material including exclusive interviews, Clark draws on his own first-hand experience of key figures integral to Alibaba's rise to create an authoritative, compelling narrative account of how Alibaba and its charismatic creator have transformed the way that Chinese exercise their new found economic freedom, inspiring entrepreneurs around the world and infuriating others, turning the tables on the Silicon Valley giants who have tried to stand in his way.

An expert insider with unrivaled connections, Clark has a deep understanding of Chinese business mindset. He illuminates an unlikely corporate titan as never before, and examines the key role his company has played in transforming China while increasing its power and presence worldwide.

"A must-read for anyone hoping to navigate China's new economy." — Financial Times

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

The Iron Triangle

China changed because of us in the past fifteen years.

We hope in the next fifteen years, the world changes because of us.

—Jack Ma

On November 11, 2015, in Beijing, in the iconic bubble-like structure bathed in blue light known popularly as the “Water Cube,” the venue for the aquatics events in the Beijing Olympics held seven years earlier, it wasn’t water that flowed but streams of data. For twenty-four hours, without interruption, a huge digital screen flickered with maps, charts, and news crawls, reporting in real time the purchases of millions of consumers across China on Alibaba’s websites. In front of hundreds of journalists broadcasting the event across China and around the world, the Water Cube had been repurposed as mission control for the Chinese middle class and the merchants marketing to them. A four-hour live TV special, the 11/11 Global Festival Shopping Gala, was broadcast to help keep shoppers up until midnight, featuring actors such as Kevin Spacey, who appeared in a filmed montage as his character from House of Cards, President Frank Underwood, endorsing Alibaba as the place to buy disposable “burner” cell phones. The gala show culminated in a skit featuring Jack’s face as the new Bond girl before he appeared in a tuxedo walking alongside Bond actor Daniel Craig for some onstage antics in the final countdown to midnight.

In the first eight minutes of 11/11/15, shoppers made more than $1 billion in purchases on Alibaba’s sites. And they kept on shopping. As the world’s largest cash register tallied the takings, Jack—seated next to his friend, the actor and martial artist Jet Li—couldn’t resist taking a photo of the huge screen with his cell phone. Twenty-four hours later, 30 million buyers had racked up over $14 billion1 in purchases, four times greater than 11/11’s U.S. equivalent, Cyber Monday, which occurred a few weeks later, after Thanksgiving’s Black Friday discount day.

Shortly after midnight, Chinese media reporting the sales figures recorded by Alibaba’s Singles’ Day promotion on November 11, 2015. Duncan Clark

In China, November 11 is Singles’ Day,2 a special annual promotion.3 In the West, the date commemorates veterans of past wars. But in China, November 11 is the most important day of the year for the merchants fighting for the wallets of the country’s newly minted consumer class.

On this day, also known as Double Eleven (shuang shiyi),4 people in China indulge in a frenzy of pure, unadulterated hedonism. Jack summed up the event: “This is a unique day. We want all the manufacturers, shop owners to be thankful for the consumers. We want the consumers to have a wonderful day.”5

From just twenty-seven merchants in 2009, over forty thousand merchants and thirty thousand brands now participate in Singles’ Day. Total sales in 2015 were up 60 percent from the $9 billion of the previous year. On that occasion, celebrated at Alibaba’s Wetlands campus in Hangzhou, the company’s chief strategy officer Dr. Zeng Ming described the scene in terms reminiscent of Dr. Frankenstein watching his creation stirring from the dead: “The ecosystem has its own will to grow.” Alibaba’s executive vice chairman Joe Tsai echoed the sentiment: “You’re seeing the unleashing of the consumption power of the Chinese consumer.”

This power has long been suppressed. Household spending in the United States drives two-thirds of the economy, but in China it barely accounts for one-third. Compared to developed countries, Chinese people don’t consume enough. The reason? They save too much and spend too little. To fund their future education, medical expenses, or retirement, many families accumulate substantial amounts of mattress money or “precautionary savings.” Also, lacking the range or quality of products on offer in the West, consumers in China until relatively recently had little enticement to spend more on themselves.

Addressing an audience at Stanford University in September 2015, Jack observed that “in the U.S. when the economy is slowing down it means people don’t have money to spend.” But, he joked, “You guys know how to spend tomorrow’s money or future money or other people’s money. China’s been poor for so many years, we put our money in the bank.”

Old habits die hard, but a new habit—buying online—is changing the way consumers in China behave. Alibaba is at the forefront of this shift. Its most popular website is Taobao.com, China’s third most visited website and the world’s twelfth. A common saying today in China is wanneng de taobao,6 meaning “you can find everything on Taobao.” Amazon has been called “the Everything Store.” Taobao too sells (almost) everything, everywhere. Just as Google is synonymous with searching online, in China to “tao”7 something is shorthand for searching for a product online.

Alibaba has a much greater impact on China’s retail sector than Amazon does in the United States. Thanks to Taobao and its sister site, Tmall, Alibaba is effectively China’s largest retailer. Amazon, by contrast, only became one of the top ten retailers in America in 2013.

Although Alibaba launched Taobao in 2003, it was only five years later that it really came into its own. Until then China’s countless factories churned out products mostly for buyers overseas, shipped to stock the shelves of retailers like Walmart and Target. But the global financial crisis in 2008 changed everything. China’s traditional export markets were thrown into a tailspin. Taobao pried open the factory gates to consumers in China instead. The Chinese government’s response to the 2008 crisis was to double down on the Old China model—pumping money into the economy that fueled a massive real estate bubble, excess capacity, and yet more pollution. As the bills came in, it became clear that the much-needed rebalancing of the Chinese economy toward consumption could no longer be postponed. And Alibaba is one of the biggest beneficiaries.

Jack likes to say that his company’s success was an accident: “Alibaba might as well be known as ‘one thousand and one mistakes.’” In its early years, he gave three explanations as to why the company survived: “We didn’t have any money, we didn’t have any technology, and we didn’t have a plan.”

But let’s look at the three real factors that underpin Alibaba’s success today: the company’s competitive edge in e-commerce, logistics, and finance, what Jack describes as Alibaba’s “iron triangle.”

Alibaba’s e-commerce sites offer an unparalleled variety of goods to consumers. Its logistics offering ensures those goods are delivered quickly and reliably. And the company’s finance subsidiary ensures that buying on Alibaba is easy and worry free.

The E-commerce Edge

Unlike Amazon, Alibaba’s consumer websites Taobao and Tmall carry no inventory.8 They serve as platforms for other merchants to sell their wares. Taobao consists of nine million storefronts run by small traders or individuals. Attracted by the site’s huge user base, these “micro merchants” choose to set up their stalls on Taobao in part because it costs them nothing to do so. Alibaba charges them no fees. But Taobao makes money—a lot of it—from selling advertising space, helping promote those merchants who want to stand out from the crowd.

Merchants can advertise through paid listings or display ads. Under the paid listing model, similar to Google’s AdWords, advertisers bid for keywords to give their products a more prominent placement on Taobao. They pay Alibaba based on the number of times consumers click on their ads. Merchants can also use a more traditional advertising model, paying based on the number of times their ads are displayed on Taobao.

The old joke about advertising is “I know at least half of my advertising budget works . . . I just don’t know which half.” But with “pay-for-performance” advertising—and a ready market of hundreds of millions of consumers—Taobao commands an enormous appeal to small merchants.

Keeping order amid Taobao’s virtual alleyways are Alibaba’s client service managers, the xiaoer.9 Thousands of xiaoer mediate any disputes that arise between customers and merchants. These referees, young employees averaging twenty-seven years old, work long hours, often sending messages to vendors late at night.

The xiaoer have great powers of enforcement, including the ability to shut down a merchant entirely. They can also offer merchants a carrot: the ability to participate in marketing campaigns. Inevitably, some merchants have sought to corrupt the xiaoer by offering bribes. Alibaba periodically shuts down merchants caught in the act, and an internal disciplinary unit is constantly on the lookout to root out graft among its employees.

But Taobao’s success is not explained by the xiaoer alone. The site works because it succeeds in putting the customer first, bringing the vibrancy of China’s street markets to the experience of shopping online. Buying online is as interactive as in real life. Customers can use Alibaba’s chat application10 to haggle over prices; a vendor might hold up a product to his webcam. Shoppers can also expect to score discounts and free shipping. Most packages arrive with some extra samples or cuddly toys thrown in, something I have personally grown so used to that when receiving Amazon packages in the United States I shake empty boxes in vain. The merchants on Taobao guard their reputation with customers fiercely; such is the Darwinian nature of the competition on the platform. When customers post a negative comment about a merchant or a product, they can expect to receive a message and offers of refunds or free replacements within minutes.

Alibaba’s e-commerce edge is also honed by another of its websites, Tmall.11 If Taobao can be compared to a collection of scrappy market stalls, Tmall is a glitzy shopping mall. Large retailers and even luxury brands sell their goods on Tmall and, for those customers not yet able to afford them, build brand awareness. Unlike Taobao, which is free for buyers and sellers, merchants pay commissions to Alibaba on the products they sell on Tmall, ranging from 3 to 6 percent depending on the category.12 Today Tmall.com is the seventh-most-visited website in China.

In Chinese, the site is called tian mao, or “sky cat.” Its mascot is a black cat, to distinguish it from Taobao’s alien doll. Tmall is increasingly important for Alibaba, generating $136 billion in gross merchandise volume for the company,13 closing in on the $258 billion sold on Taobao. Alibaba earns almost $10 billion a year in revenue from these sites, nearly 80 percent of its total sales.

Tmall hosts three types of stores on its platform: flagship stores, run by a brand itself; authorized stores, set up by a merchant licensed to do so by the brand; and specialty stores, which carry the goods of more than one brand. The specialty stores account for 90 percent of Tmall vendors. More than seventy thousand brands, from China and overseas, can be found today on Tmall.

In the Singles’ Day promotion on Tmall, the most popular brands included foreign names such as Nike, Gap, Uniqlo, and L’Oréal as well as domestic players such as smartphone vendors Xiaomi and Huawei, and consumer electronics and home appliances company Haier.

Tmall is a veritable A to Z of brands, from Apple to Zara. Luxury brands also sell on the website, although they are careful14 not to cannibalize sales in their physical stores. The presence of Burberry on the site is a sign that Alibaba is no longer just about cheap goods.

U.S. retailers like Costco and Macy’s are also on Tmall, part of a drive by Alibaba to connect them along with other overseas stores to customers in China. Costco’s Tmall store drew over 90 million visitors to its site in the first two months.

Even Amazon is on Tmall, selling imported food, shoes, toys, and kitchenware since 2015. Amazon has long had designs on the China market but has had to settle for just 2 percent of it.

In addition to Taobao and Tmall, Alibaba operates a Groupon-style15 site called Juhuasuan.com.16 Juhuasuan is the largest product-focused group-buying site in China. Buoyed by the huge volume of goods on Alibaba’s other sites, it has signed up more than 200 million users, making it the largest online group-buying site in the world. Together, Taobao, Tmall, and Juhuasuan have signed up over 10 million merchants, offering more than one billion individual items for sale.

Alibaba’s websites are popular in part because, as in the United States, shopping online from home can save time and money. More than 10 percent of retail purchases in China are made online, higher than the 7 percent in the States. Jack has likened e-commerce to a “dessert” in the United States, whereas in China it is the “main course.” Why? Shopping in China was never a pleasurable experience. Until the arrival of multinational companies like Carrefour and Walmart, there were very few retailing chains or shopping malls. Most domestic retailers started as state-owned enterprises (SOEs). With access to a ready supply of financing, provided by local governments or state-owned banks, they tended to view shoppers as a mere inconvenience. Other retailers were set up by real estate companies more concerned with the value of the land underneath their store than with the customers within.

A key factor in the success of e-commerce in China is the burden of real estate on traditional retailers. Land is expensive in China because it is a crucial source of income for the government. Land sales account for one-quarter of the government’s fiscal revenues. At the local government level they account for more than one-third. One prominent e-commerce executive summed it up for me: “Because of the way our economy is structured, the government has a lot of resources. The government decides the price of land. The government decides how resources are channeled, where money is spent. The government relies too heavily on taxes and fees associated with selling land. That almost destroyed the retail business in China, and pushed a lot of deman...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Maps

- Introduction

- Chapter One: The Iron Triangle

- Chapter Two: Jack Magic

- Chapter Three: From Student to Teacher

- Chapter Four: Hope and Coming to America

- Chapter Five: China Is Coming On

- Chapter Six: Bubble and Birth

- Chapter Seven: Backers: Goldman and SoftBank

- Chapter Eight: Burst and Back to China

- Chapter Nine: Born Again: Taobao and the Humiliation of eBay

- Chapter Ten: Yahoo’s Billion-Dollar Bet

- Chapter Eleven: Growing Pains

- Chapter Twelve: Icon or Icarus?

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- About the Author

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Alibaba by Duncan Clark in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Biografie in ambito aziendale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.