- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

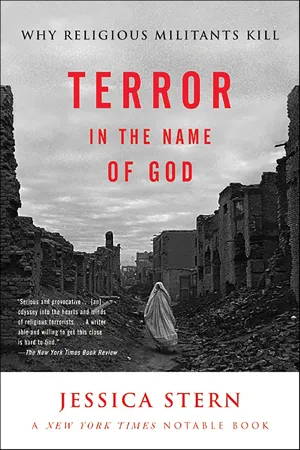

An expert in violent extremism delivers a "serious and provocative . . . odyssey into the hearts and minds of religious terrorists" from Pakistan to Oklahoma (

The New York Times Book Review).

A New York Times Notable Book

For four years, Jessica Stern interviewed extremist members of three religions around the world: Christians, Jews, and Muslims. Traveling extensively—to refugee camps in Lebanon, to religious schools in Pakistan, to prisons in Amman, Asqelon, and Pensacola—she discovered that the Islamic jihadi in the mountains of Pakistan and the Christian fundamentalist bomber in Oklahoma have much in common.

Based on her vast research, Stern lucidly explains how terrorist organizations are formed by opportunistic leaders who—using religion as both motivation and justification—recruit the disenfranchised. She depicts how moral fervor is transformed into sophisticated organizations that strive for money, power, and attention.

Jessica Stern's extensive interaction with the faces behind the terror provide unprecedented insight into acts of inexplicable horror, and enable her to suggest how terrorism can most effectively be countered.

"[A] sophisticated examination of religiously motivated terrorism"— The New Yorker

A New York Times Notable Book

For four years, Jessica Stern interviewed extremist members of three religions around the world: Christians, Jews, and Muslims. Traveling extensively—to refugee camps in Lebanon, to religious schools in Pakistan, to prisons in Amman, Asqelon, and Pensacola—she discovered that the Islamic jihadi in the mountains of Pakistan and the Christian fundamentalist bomber in Oklahoma have much in common.

Based on her vast research, Stern lucidly explains how terrorist organizations are formed by opportunistic leaders who—using religion as both motivation and justification—recruit the disenfranchised. She depicts how moral fervor is transformed into sophisticated organizations that strive for money, power, and attention.

Jessica Stern's extensive interaction with the faces behind the terror provide unprecedented insight into acts of inexplicable horror, and enable her to suggest how terrorism can most effectively be countered.

"[A] sophisticated examination of religiously motivated terrorism"— The New Yorker

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Terror in the Name of God by Jessica Stern in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Global Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Grievances

That Give Rise

to Holy War

Part 1 of this book explores the kinds of grievances that give rise to terrorism in the name of God. We learn in the first half of this book how leaders exploit feelings of alienation and humiliation to create holy warriors; and how demographic shifts, selective reading of history, and territorial disputes are used to justify holy wars.

Part 1 addresses the question: Why do some people respond to these religious grievances by joining terrorist groups, and once they join, what makes them stay? We learn, through the terrorists’ stories, that the benefits they receive are partly spiritual, partly emotional, and partly material. Terrorism involves a collective-action problem, in the sense that only those who contribute incur the costs, but a broader collective shares the benefits. The theory of collective action suggests that people tend to “free ride” on others’ contributions to collective goods. It suggests, for example, that it is irrational to pay taxes if there is no enforcement mechanism because we can reap the benefits of others’ contributions whether or not we write a check to the government.1 It is possible to encourage collective action through positive incentives (rewards or payments) or penalties for noncompliance (corporal punishment, incarceration, or fines).

When Jewish extremists attempt to lay a cornerstone for the Third Temple they hope to build, all like-minded messianic Jews (and messianic Christians) benefit. Only the participants pay: When they ascend the Temple Mount, they incur risks to their person, livelihood, freedom, and families. Given this, the extremist should be asking himself: Why bother participating? Why not let others do the work and take the risks?

Participation in terrorist violence can be seen as kind of tax paid to redress the collectives’ grievances. Those who contribute their lives, their money, or their support are paying their taxes; those who do not are free riders. The metaphor may sound far-fetched, but an Al Qaeda member has used precisely this language to chastise non-violent Muslims who don’t contribute to Al Qaeda’s goals. Ramzi bin al-Shibh, a mastermind of the September 11 attacks, describes violence as “the tax” that Muslims must pay “for gaining authority on earth.” He says that “it is imperative to pay a price for Heaven, for the commodity of Allah is dear, very dear. It is not acquired through rest, but [rather] blood and torn-off limbs must be the price.” The moral “obligation of jihad” is equally important as the duties of prayer and charity, he says. He urges Muslims to “grasp this understanding,” claiming that the punishment awaiting those who neglect the obligation to pay their “taxes” by waging jihad will be “painful and harsh.”2

Terrorist leaders encourage operatives to participate in terrorist violence by holding out the promise of heavenly rewards or the threat of heavenly retribution. Some operatives participate because they fear being punished in the afterlife, as Ramzi bin al-Shibh suggests, or because they desire to be virtuous (in their view) for its own sake. But leaders also offer material and emotional incentives—both rewards and punishments. They provide cash payments for successful operations. They provide money to “martyrs’ ” families. Recruiters in Kashmir coerce families into donating their sons by demanding large payments or the use of a child. One Al Qaeda recruit told his interrogators that the atmosphere at the training camps was one of intense psychological pressure enforced by the torture of those who did not embrace the violent code.3

Some operatives will admit they got involved in terrorism out of a desire for adventure.4 Many join out of friendship or through social networks. In some cases, the desire to be with friends turns out to be more important, over time, than the desire to achieve any particular goal. Others are attracted to the “glamour” of belonging to a militant group. One operative told me about the appeal of living outside normal society under extreme conditions, on a kind of permanent Outward Bound. Some get involved in violent groups out of a sense of alienation and anomie. Once part of a well-armed group, the weak feel strong and powerful, perhaps for the first time in their lives. Some admit that they find guns and violence appealing. For such individuals, there are clear emotional benefits to belonging to violent groups. In short, fun and profit—status, glamour, power, prestige, friendship, and money—provide powerful incentives for participating in terrorist groups.

But fun and profit do not explain the whole picture. Foot soldiers are likely to receive no monetary compensation. They are often recruited from extremist religious seminaries where they are indoctrinated from an early age about the spiritual importance of donating their lives to a holy war. The September 11 hijackers apparently were not paid. Fun and profit also do not explain how an organization begins. “Why and how…the group committed from the start to fundamental transformation of the structure of power…remains one of the mysteries of our time,” sociologist Charles Tilly famously observed in regard to social movements.5 And yet revolutions and violent social movements do come about, much to the puzzlement of rational choice theorists. Something other than fun and profit appears to be at play.6

In real life (as opposed to elegant, parsimonious theory), people have mixed motives for everything they do. We may desire to do the right thing, but we may want our efforts to be noticed and rewarded—perhaps by God, perhaps by other people. Terrorists, similarly, have mixed motives. They see themselves as purifying the world. They believe that murdering the group’s “enemies” is a way to “do good” or to “be good.”7 As some terrorists define it, virtue may be its own reward. But operatives may be influenced simultaneously by more pragmatic incentives, possibly including money for themselves or their families.

What seems to be most appealing about militant religious groups—whatever combination of reasons an individual may cite for joining—is the way life is simplified. Good and evil are brought out in stark relief. Life is transformed through action. Martyrdom—the supreme act of heroism and worship—provides the ultimate escape from life’s dilemmas, especially for individuals who feel deeply alienated and confused, humiliated or desperate.

When religious terrorist groups form, ideology and altruism play significant roles. Commitment to the goals of the organization, and the spiritual benefits of contributing to a “good cause” are sufficient incentives for many operatives, especially in the initial phase of the organization. Over time, in some cases, cynicism takes hold. Terrorism becomes a career as much as a passion. What starts out as moral fervor becomes a sophisticated organization. We will find in the pages that follow that grievance can end up as greed—for money, political power, or attention.

Astute leaders take advantage of the variety of motives that lead operatives to become terrorists. They do not rely on terrorists’ (mistaken) moral convictions alone to sustain the group over time. They offer friendship, status, adventure, “glamour,” and jobs. In commander and cadre-style organizations, leaders also realize they need a variety of recruits, some of whom will require material incentives in addition to moral, spiritual, or emotional ones.8

Although each chapter is named after a single grievance (alienation, humiliation, demographic shifts, historical wrongs, and claims over territory), multiple grievances play a role in the religious conflicts highlighted in these chapters, not just the one mentioned in the chapter’s title. The goals of the terrorists discussed in part 1 also vary along three dimensions: from spiritual to temporal, from instrumental to expressive, and from ideological to profit-driven.

All the terrorists discussed in part 1 claim to be motivated by religious principles, but most pursue a mixture of spiritual and political goals. At the extreme religious end of the spectrum are the groups seeking eternal, spiritual goals such as redemption or helping to bring on the apocalypse and the Endtimes predicted in biblical texts. The Covenant, the Sword, and the Arm of the Lord, the Christian cult discussed in chapter 1, and the Jewish Underground, one of the terrorist groups discussed in chapter 4, probably come closest to this ideal type. Both were interested in influencing the process and timing of the apocalypse. Neither was seeking political power, at least when they started out. At the opposite end of the spectrum are the groups that are mainly pursuing temporal, pragmatic goals on this earth. They may propose to impose religious laws, but their principal interests are obtaining political power or expanding their territory. For example, some of the worst religious violence in Indonesia, discussed in chapter 3, has arisen in areas where indigenous groups living in natural-resource rich regions are seeking greater autonomy or independence. Hamas, discussed in chapter 2, claims to be protecting coreligionists from assault by other religious groups, but is largely focused on achieving political power and asserting control over the whole of Israel. Jewish extremist Avigdor Eskin invoked an ancient mystical prayer to bring about the death of Israeli Prime Minister Rabin. Despite his fascination with mysticism, however, Eskin is mainly interested in altering the situation in this world. He wanted Rabin to die because he was giving away “Jewish” territory to Muslims. Eskin and others discussed in the chapter are raising money to create a “genuine” right-wing party in Israel.

Terrorists also vary in their desire to accomplish something. Sometimes they are businesslike in their pursuit of objectives. The objective could be to frighten the enemy or damage an economy. It could be to force the enemy to overreact, thereby demonstrating his ruthlessness or weakness. It could be to impose religious laws. But sometimes the purpose is expressive rather than instrumental. The aim is to convey rage or to exact revenge with little thought to long-term consequences. For whom is the message intended? Usually we think of the audience for terrorism as the victims and their sympathizers. But attacks sometimes have more to do with rousing the troops than terrorizing the victims. Bin Laden, for example, appears to believe that spectacular attacks make him more appealing to his followers. In his words, people follow the strong horse, and abandon the weak one.

Terrorists groups also vary in terms of the extent to which ideology matters. Some terrorist organizations transform themselves, over time, into profit-driven organizations for which crime is an end rather than a means. These groups switch from grievance to greed.

The groups discussed in part 1 also vary in size, organizational sophistication, and potential to cause mass casualties. Some engage in terrorism essentially full time; while others engage in terrorism as a kind of hobby. Some are mainly involved in fighting enemy troops, resorting to terrorism (targeting noncombatants) only occasionally. For still others, the charitable and political wings of the organization are equally as important as the military ones.

One

Alienation

This chapter tells the story of a group of alienated individuals who joined a religious fellowship in rural Arkansas. After the leader received a “revelation” that the Endtimes had begun, the cult began “fusing together in one body” as directed by a prophetess living on the compound. They burned family photographs, sold their wedding rings, pooled their earnings, and destroyed televisions and other “reminders of the outside world’s propaganda.” They also began stockpiling weapons to prepare for the “enemy’s” anticipated invasion. But the Apocalypse—and the battle between good and evil forces—failed to materialize on the appointed hour. Each failed prophecy was followed by a revised forecast. Instead of giving in to despair that their dream of the Endtimes might not materialize, cult members’ confidence grew stronger. They intensified their military training, acquired more powerful weapons, and purified themselves to prepare to vanquish the forces of evil.

By examining this cult, we learn how leaders develop a story about imminent danger to an “in group,” foster group identity, dehumanize the group’s purported enemies, and encourage the creation of a “killer self” capable of murdering large numbers of innocent people. This chapter focuses on the evolution of a cult member named Kerry Noble. We observe how the leader cunningly capitalized on Noble’s need to feel important inside the group, and how, over time, Noble was transformed from a gentle but frustrated pastor seeking transcendence to a terrorist prepared to countenance “war” against the cult’s enemies—blacks, Jews, “mud people,” and the U.S. government.

On April 19, 1985, two hundred federal and state law-enforcement agents staged a siege at a 240-acre armed compound in rural Arkansas inhabited by a Christian cult called the Covenant, the Sword, and the Arm of the Lord (CSA).1 The cult had long been expecting an enemy invasion, and members had laid land mines around the periphery of the property. They had stockpiled five years’ worth of food. James Ellison, the commander of the cult, wanted to shoot it out with the feds. Danny Coulson, head of the FBI’s Hostage Rescue Team, eventually persuaded Ellison that the cult would lose such a battle. Coulson said he had a Huey helicopter, just over the hill, which would level the place if a cult member fired a single shot. He also said that an aircraft circling the property was equipped with heat-seeking devices. “We can watch your every move, day or night,” he said. He told cult members that he had an armored personnel carrier around the bend, and weapons so advanced and new that the military didn’t have them yet. “Your organization is considered by the government to be the best-trained civilian paramilitary group in America. That’s why we’re here. We’re only sent against the best,” he told the cult’s second-in-command, Kerry Noble, who had been sent to negotiate with the enemy.2

The FBI asked the Reverend Robert Millar, a leading cleric of the American racist right, to help negotiate with the cult. Millar reports that he saw 150 men in camouflage, plus FBI and ATF agents, a SWAT team, and “a few Mossad agents,” scattered in the woods around the compound, whom he blamed for provoking a “tense and dangerous confrontation.”3 “If it comes to a fight, hand me a gun, show me how to use it, and I am with you,” he says he told Ellison.4

Three days after the siege began, the Covenant’s “Home Guard” surrendered. The Reverend Millar was disappointed. “It ended with the whole group walking out, the womenfolk carrying their Bibles and singing, the men handing over their carbines.”5 When government officials searched the compound, they found a large cache of weapons, including fifty hand grenades; seventy-four assault weapons; thirty machine guns; six silencers; an M-72 antitank rocket; a World War II–era antiaircraft gun; three half-pou...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Notes

- Searchable Terms

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Praise for

- Also by Jessica Stern

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher