- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Childhood

1974-1982

“Well, it's no use your talking about waking him,” said Tweedledum, “when you're only one of the things in his dream. You know very well you're not real.” “

I am real!” said Alice, and began to cry. “

You won't make yourself a bit realer by crying,” Tweedledee remarked: “there's nothing to cry about.” “

If I wasn't real,” Alice said—half laughing through her tears, it all seemed so ridiculous—“I shouldn't be able to cry.” “

I hope you don't think those are real tears?” Tweedledee interrupted in a tone of great contempt.

—Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

It was that simple: One minute I was your average nine-year-old, shorts and a T-shirt and long brown braids, sitting in the yellow kitchen, watching Brady Bunch reruns, munching on a bag of Fritos, scratching the dog with my foot. The next minute I was walking, in a surreal haze I would later compare to the hum induced by speed, out of the kitchen, down the stairs, into the bathroom, shutting the door, putting the toilet seat up, pulling my braids back with one hand, sticking my first two fingers down my throat, and throwing up until I spat blood.

Flushing the toilet, washing my hands and face, smoothing my hair, walking back up the stairs of the sunny, empty house, sitting down in front of the television, picking up my bag of Fritos, scratching the dog with my foot.

How did your eating disorder start? the therapists ask years later, watching me pick at my nails, curled up in a ball in an endless series of leather chairs. I shrug. Hell if I know, I say.

I just wanted to see what would happen. Curiosity, of course, killed the cat.

It wouldn't hit me, what I'd done, until the next day in school. I would be in the lunchroom of Concord Elementary, Edina, Minnesota, sitting among my prepubescent, gangly friends, hunched over painful nubs of breasts and staring at my lunch tray. I would realize that, having done it once, I'd have to keep doing it. I would panic. My head would throb, my heart do a little arrhythmic dance, my newly unbalanced chemistry making it seem as though the walls were tilting, the floor undulating beneath my penny-loafered feet. I'd push my tray away. Not hungry, I'd say. I did not say: I'd rather starve than spit blood.

And so I went through the looking glass, stepped into the netherworld, where up is down and food is greed, where convex mirrors cover the walls, where death is honor and flesh is weak. It is ever so easy to go. Harder to find your way back.

I look back on my life the way one watches a badly scripted action flick, sitting at the edge of the seat, bursting out, “No, no, don't open that door! The bad guy is in there and he'll grab you and put his hand over your mouth and tie you up and then you'll miss the train and everything will fall apart!” Except there is no bad guy in this tale. The person who jumped through the door and grabbed me and tied me up was, unfortunately, me. My double image, the evil skinny chick who hisses, Don't eat. I'm not going to let you eat. I'll let you go as soon as you're thin, I swear I will. Everything will be okay when you're thin.

Liar. She never let me go. And I've never quite been able to wriggle my way free.

California

Five years old. Gina Lucarelli and I are standing in my parents' kitchen, heads level with the countertops, searching for something to eat. Gina says. You guys don't have any normal food. I say apologetically, I know. My parents are weird about food. She asks, Do you have any chips? No. Cookies? No. We stand together, staring into the refrigerator. I announce, We have peanut butter. She pulls it out, sticks a grimy finger into it, licks it off. It's weird, she says. I know, I say. It's unsalted. She makes a face, says, Ick. I agree. We stare into the abyss of food that falls into two categories: Healthy Things and Things We Are Too Short to Cook—carrots, eggs, bread, nasty peanut butter, alfalfa sprouts, cucumbers, a six-pack of Diet Lipton Iced Tea in blue cans with a little yellow lemon above the word Tea. Tab in the pink can. I offer, We could have toast. She peers at the bread and declares, It's brown. We put the bread back. I say, inspired, We have cereal! We go to the cupboard, the one by the floor. We stare at the cereal. She says, It's weird. I say, I know. I pull out a box, look at the nutritional information, run my finger down the side and authoritatively note, It only has five grams of sugar in it. I stick my chin up and brag, We don't eat sugar cereals. They make you fat. Gina, competitive, says, I wouldn't even eat that. I wouldn't eat anything with more than two grams of sugar. I say, Me neither, put the cereal back, as if it's contaminated. I bounce up from the floor, stick my tongue out at Gina. I'm on a diet, I say. Me too, she says, face screwing up in a scowl. Nuh-uh, I say. Uh-huh, she retorts. I turn my back and say, Well, I wasn't hungry anyway. Me neither, she says. I go to the fridge, make a show of taking out a Diet Lipton Iced Tea with Little Yellow Lemon, pop it open, sip loudly, tttthhhpppttt. It tastes like sawdust, dries out my mouth. See? I say, pointing to Diet, I'm gonna be as thin as my mom when I grow up.

I think of Gina's mom, who I know for a fact buys sugar cereal. I know because every time I sleep over there we have Froot Loops for breakfast, the artificial colors turning the milk red. Gina and I suck it up with straws, seeing who can be louder.

Your mom, I say out of pure spite, is fat.

Gina says, At least my mom knows how to cook.

At least my mom has a job, I shout.

At least my mom is nice, she sneers.

I clock her. She cries. Baby, I say. I flounce out onto the deck, climb onto the picnic table, pull on my blue plastic Mickey Mouse sunglasses, imagining that I am the sophisticated bathing suit lady in the Diet Lipton Iced Tea commercials, tan and long and thin. I lean back casually, lift the can to my mouth. I begin to take a bitter sip and spill it all over my shirt.

That night, while my father is cooking dinner, I lean against his knees and announce, I'm not hungry. I'm on a diet. My father laughs. Feet dangling from my chair at the table, I stare at the food, push it around, glance surreptitiously at my mother's plate, her nervous little bites. The way she leans back in her chair, setting down her fork to gesture rapidly with her hands as she speaks. My father, bent over his plate, eating in huge bites. My mother shoves her dinner away, precisely half eaten. My father tells her she wastes food, that he hates the way she always wastes food. My mother snaps back defensively, I'm full, dear. Glares. I push my plate away, say loudly, I'm full.

And all eyes turn to me. Come on, Piglet, says my mother. A few more bites. Two more, she says.

Three, says my father. They glare at each other.

I eat a pea.

I was never normal about food, even as a baby. My mother was unable to breast-feed me because it made her feel as if she were being devoured. I was allergic to cow's milk, soy milk, rice milk. My parents had to feed me a vile concoction of ground lamb and goat's milk that made them both positively ill. Apparently I guzzled it up. Later they gave me orange juice in a bottle, which rotted my teeth. I suspect that I may not even have been normal about food in utero; my mother's eating habits verge on the bizarre. As a child, I had endless food allergies. Sugar, food coloring, and preservatives sent me into hyperactive orbit, sleepless and wild for days. My parents were usually good about making sure that we had dinner together, that I ate three meals a day, that I didn't eat too much junk food and ate my vegetables. They were also given to sudden fits of paranoid “healthy eating,” or fast-food eating, or impulsive decisions to dine out at 11 P.M. (as I slid under the table, asleep).

I have had moments of appearing normal: eating pizza at girlhood slumber parties, a cream puff on Valentine's Day when I was nine, a grilled cheese sandwich as I hung upside down off the big black chair in the living room when I was four. It is only now, in context, that these things seem strange—the fact that I remember, in detail, the pepperoni pizza, the way we all ostentatiously blotted the grease with our paper napkins, and how many slices I ate (two), and how many slices every other girl ate (two, except for Leah, who ate one, and Joy, who ate four), and the frantic fear that followed, that my rear end had somehow expanded and now was busting out of my shortie pajamas. I remember begging my mother to make cream puffs. I remember that before the cream puffs we had steak and peas. I also recall my mother making grilled cheese sandwiches or scrambled eggs for me on Saturday afternoons when everything was quiet and calm. They were special because she made them, and so I have always associated grilled cheese sandwiches and scrambled eggs with quiet and my mother and calm. Some people who are obsessed with food become gourmet chefs. Others get eating disorders.

I have never been normal about my body. It has always seemed to me a strange and foreign entity. I don't know that there was ever a time when I was not conscious of it. As far back as I can think, I was aware of my corporeality, my physical imposition on space.

My first memory is of running away from home for no particular reason when I was three. I remember walking along Walnut Boulevard, in Walnut Creek, California, picking roses from other peoples' front yards. My father, furious and worried, caught me. I remember being carted home by the arm and spanked, for the first and last time in my life. I hollered like hell that he was mean and rotten, and then hid in the clothes hamper in my mother's closet. I remember being delighted that I was precisely the right size to fit in the clothes hamper so I could stay there forever and ever. I sat there in the dark like a mole, giggling. I remember the whole thing as if I were watching myself: I see me being spanked from across the room, I see me hiding in the hamper from above. It's as if a part of my brain had split off and was keeping an eye on me, making sure I knew how I looked at all times.

I feel as if a small camera was planted on my body, recording for posterity a child bent over a scraped knee, a child pushing her food around her plate, a child with her foot on the floor while her half-brother tied her shoe, a child leaning over her mother's chair as her mother did magic things with cotton and lace. Dresses, like angels, appeared and fluttered from a hanger on the door. A child in the bathtub, looking down at her body submerged in the water as if it were a separate thing inexplicably attached to her head.

My memory of early life veers back and forth from the sensate to the disembodied, from specific recall of the smell of my grandmother's perfume to one of slapping my own face because I thought it was fat and ugly, seeing the red print of my hand but not feeling the pain. I do not remember very many things from the inside out. I do not remember what it felt like to touch things, or how bathwater traveled over my skin. I did not like to be touched, but it was a strange dislike. I did not like to be touched because I craved it too much. I wanted to be held very tight so I would not break. Even now, when people lean down to touch me, or hug me, or put a hand on my shoulder, I hold my breath. I turn my face. I want to cry.

I remember the body from the outside in. It makes me sad when I think about it, to hate that body so much. It was just a typical little girl body, round and healthy, given to climbing, nakedness, the hungers of the flesh. I remember wanting. And I remember being at once afraid and ashamed that I wanted. I felt like yearning was specific to me, and the guilt that it brought was mine alone.

Somehow, I learned before I could articulate it that the body—my body—was dangerous. The body was dark and possibly dank, and maybe dirty. And silent, the body was silent, not to be spoken of. I did not trust it. It seemed treacherous. I watched it with a wary eye.

I will learn, later, that this is called “objectification consciousness.” There will be copious research on the habit of women with eating disorders perceiving themselves through other eyes, as if there were some Great Observer looking over their shoulder. Looking, in particular, at their bodies and finding, more and more often as they get older, countless flaws.

I remember my entire life as a progression of mirrors. My world, as a child, was defined by mirrors, storefront windows, hoods of cars. My face always peered back at me, anxious, checking for a hair out of place, searching for anything that was different, shorts hiked up or shirt untucked, butt too round or thighs too soft, belly sucked in hard. I started holding my breath to keep my stomach concave when I was five, and at times, even now, I catch myself doing it. My mother, as I scuttled along sideways beside her like a crab, staring into every reflective surface, would sniff and say, Oh, Marya. You're so vain.

That, I think, was inaccurate. I was not seeking my image in the mirror out of vain pride. On the contrary, my vigilance was something else—both a need to see that I appeared, on the surface at least, acceptable, and a need for reassurance that I was still there.

I was about four when I first fell into the mirror. I sat in front of my mother's bathroom mirror singing and playing dress up by myself, digging through my mother's huge magical box of stage makeup that sighed a musty perfumed breath when you opened its brass latch. I painted my face with elaborate greens and blues on the eyes, bright streaks of red on the cheeks, garish orange lipstick, and then I stared at myself in the mirror for a long time. I suddenly felt a split in my brain: I didn't recognize her. I divided into two: the self in my head and the girl in the mirror. It was a strange, not unpleasant feeling of disorientation, dissociation. I began to return to the mirror often, to see if I could get that feeling back. If I sat very still and thought: Not me-not me-not me over and over, I could retrieve the feeling of being two girls, staring at each other through the glass of the mirror.

I didn't know then that I would eventually have that feeling all the time. Ego and image. Body and brain. The “mirror phase” of child development took on new meaning for me. “Mirror phase” essentially describes my life.

Mirrors began to appear everywhere. I was four, maybe five years old, in dance class. The studio, up above Main Street, was lined with mirrors that reflected Saturday morning sun, a hoard of dainty little girls in baby blue leotards, and me. I had on a brand-new blue leotard, not baby blue, but bright blue. I stuck out like an electric blue thumb, my ballet bun always coming undone. I was standing at the barre, looking at my body repeated and repeated and repeated, me in my blue leotard standing there, suddenly horrified, trapped in the many-mirrored room.

I am not a waif. Not now, not then. I'm solid. Athletic. A mesomorph: little fat, lot of muscle. I can kick a ball pretty casually from one end of a soccer field to the other, or bloody a guy's nose without really trying, and if you hit me real hard in the stomach you'd probably break your hand. In other words I am built for boxing, not ballet.1 I came that way—even baby pictures show my solid diapered self tromping through the roses, tilted forward, headed for the gate. But at four I stood, a tiny Eve, choked with mortification at my body, the curve and plane of belly and thigh. At four I realized that I simply would not do. My body, being solid was too much. I went home from dance class that day, put on one of my father's sweaters, curled up on my bed, and cried. I crept into the kitchen that evening as my parents were making dinner, the corner of the counter just above my head. I remember telling them, barely able to get the sour confession past my lips: I'm fat.

Since I was nothing of the sort, my parents had no good reason to think that I honest-to-god believed that. They both made the face, a face I would learn to despise, that oh please Marya don't be ridiculous face, and made the sound, a terrible sound, that dismissive sound, ttch. They kept making dinner. I slapped my littl...

Table of contents

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Childhood

- 2 Bulimia

- 3 The Actor’s Part

- Interlude

- Interlude

- Interlude

- Afterword

- Present Day

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Praise

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

- Footnotes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

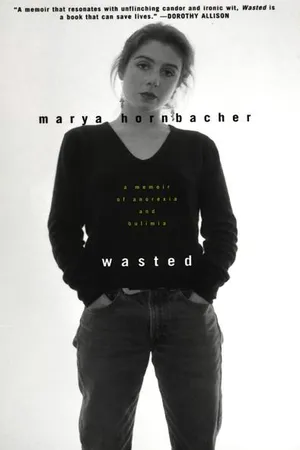

Yes, you can access Wasted by Marya Hornbacher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Fashion Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.