- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

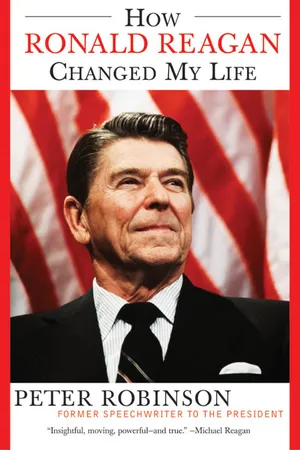

How Ronald Reagan Changed My Life

About this book

As a young speechwriter in the Reagan White House, Peter Robinson was responsible for the celebrated "Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall" speech. He was also one of a core group of writers who became informal experts on Reagan -- watching his every move, absorbing not just his political positions, but his personality, manner, and the way he carried himself. In How Ronald Reagan Changed My Life, Robinson draws on journal entries from his days at the White House, as well as interviews with those who knew the president best, to reveal ten life lessons he learned from the fortieth president -- a great yet ordinary man who touched the individuals around him as surely as he did his millions of admirers around the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access How Ronald Reagan Changed My Life by Peter Robinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Four

TEAR DOWN THIS WALL

Words Matter

JOURNAL ENTRY, BERLIN, MAY 2002:

Although I only needed to be driven to my hotel, when I climbed into the cab after landing at Tegel Airport this morning I realized I could tell the driver to take me anywhere I wanted. To East Berlin? To East Berlin. Or to Potsdam, Leipzig, or Dresden. For that matter, if I’d had the fare I could have told the driver to head east until we hit Moscow.

The wall is gone.

Bugle Boy

THIS MAY SOUND like an odd admission coming from a former speechwriter, but when I first joined the President’s staff I sometimes wondered whether his speeches really mattered. It didn’t help, I suppose, that as the youngest member of the staff I got stuck early on with a lot of assignments the other speechwriters wanted to avoid. Looking over the records in the Reagan Library recently, I found that during my first year I wrote more than 150 speeches, radio talks, toasts, and sets of talking points, at least half of them forgettable. Consider, for example, the remarks I composed for the 1984 Rose Garden ceremony to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp, a name I am not making up. Purchased each year by hunters, the Duck Stamp, as it was also known, produced revenues used to preserve waterfowl habitat. The ceremony itself may have held some importance—for all I know, it helped the President carry states that contained high concentrations of hunters on Election Day later that year. But the words I composed? Let’s put it this way: You won’t find them in Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations.

As I thought about his speeches those first months, I found myself pondering Reagan’s entire political career. Since I’d spent a year and a half working for Vice President Bush before joining the President’s staff, contrasts between Bush and Reagan came readily to mind. George Bush, I recognized, spent a lot of his time tending to what I came to think of as his network. Aboard Air Force Two after giving a speech, the Vice President would sit down, pull out a stack of engraved note cards, then compose thank-you notes to all the officeholders, businessmen, and Republican officials who had sat with him at the head table. When he got done, he’d begin placing telephone calls. Listening to him, you’d find yourself wondering whether there was a single member of either the old corporate establishment in the Northeast or the new oil, gas, and real estate establishment of the Southwest with whom he wasn’t on a first-name basis. Last the Vice President might place a few calls to his family, getting in touch with siblings and offspring throughout the country. His brothers, Prescott, Johnny, and Bucky, lived, respectively, in Connecticut, New York, and Missouri, while his sister, Nancy, lived in Massachusetts. His sons, George, Jeb, Neil, and Marvin, lived, respectively, in Texas, Florida, Colorado, and Virginia, while his daughter, Doro, lived in Maine. Six degrees of separation? For Bush, that would have been about four degrees too many. Virtually every person of consequence in the entire country was either a personal acquaintance of Bush himself, of a member of his family, or of one of his friends.

A lot of politicians, I saw, possessed networks like that of George Bush. Richard Nixon was famous for his ability to greet Republican officeholders and party officials in every region of the country by name. Lyndon Johnson spent a lifetime performing political favors while committing to memory the identities of each of those on whom he had bestowed his largesse. John Kennedy’s network included his father’s business associates, his many siblings and their friends, and the intellectual establishment of the Eastern Seaboard, with which he ingratiated himself by bringing prominent academics such as John Kenneth Galbraith and Arthur Schlesinger Jr. into his administration. Franklin Roosevelt used to amuse guests by inviting them to draw a line across a map of the United States, then identifying the leading Democrats in each county through which the line passed. Franklin Roosevelt, John Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, George Bush—each possessed his own enormous network.

In this regard, I realized, Ronald Reagan proved utterly atypical. Although, like Nixon and Johnson, he had come from a family of no social or business standing, unlike Nixon and Johnson he had never attempted to compensate for his lack of family connections by working with special zeal to establish a network from scratch. When a member of his staff asked him to place a telephone call to an officeholder or supporter, Reagan was always happy enough to comply. But pick up the telephone on his own? “Very rarely did you ever see him call anyone just to say ‘howdy,’” Michael Reagan says. And although he wrote a lot of letters, Reagan displayed the same pattern when he became a politician that he had displayed as a movie star, addressing most of his correspondence to ordinary citizens, not to people of political consequence. He enjoyed keeping in touch with his fans, but he never demonstrated much enthusiasm for cultivating the powerful.

How had Reagan done it? What had he possessed that had enabled him to capture the highest office in the nation without an enormous network of the kind on which so many other politicians depended? Maybe the reason it took me a while to see the answer was that as a speechwriter I was so close to it. I kept thinking Reagan must have developed some political trick or technique that he kept tucked away, reserving it for his own use alone. But the answer lay in plain sight. What Reagan had possessed, I finally recognized, was words. Just words.

“Not too long ago two friends of mine were talking to a Cuban refugee, a businessman who had escaped from Castro,” Reagan said in the televised 1964 speech on behalf of Barry Goldwater that established him as a national figure. “And in the midst of his story one of my friends turned to the other and said, ‘We don’t know how lucky we are.’”

And the Cuban stopped and said, “How lucky you are! I had someplace to escape to.” In that sentence he told us the entire story. If we lose freedom here, there is no place to escape to. This is the last stand on earth. And this idea that government is beholden to the people, that it has no other source of power except the sovereign people, is still the newest and most unique idea in all the long history of man’s relation to man….

You and I have a rendezvous with destiny. We will preserve for our children this, the last best hope of man on earth, or we will sentence them to take the first step into a thousand years of darkness. If we fail, at least let our children and our children’s children say of us we justified our brief moment here. We did all that could be done.

It might have been almost twenty years since Reagan delivered that speech by the time I read it in the White House, but I still found it powerful. It moved me. It rang in my ears. I know this isn’t exactly an original simile, but I was never able to think of a better one. The words sounded like the call of a trumpet. In the old war movies I used to watch on Saturday afternoons when I was a kid—the cavalry fighting the Indians, the Union soldiers the Confederates, or the British the Zulus—it was always the same. The battlefield would begin to dissolve in confusion, the good guys finding themselves forced steadily back. Then a bugle or trumpet would sound, piercing the din. The good guys would cheer, rally, and then press on to victory. Reagan had no need for an enormous network because his speeches alone proved capable of rallying the American people to his cause. (While working on this book, my assistant learned that her mother found Reagan’s 1964 speech so powerful that she went door to door in her Pasadena neighborhood, giving a copy of the speech to each of her neighbors.) Not all his speeches produced the same trumpetlike effect—not, obviously, his remarks on behalf of the Duck Stamp. But did Reagan’s speeches matter? Enough, I realized, to make him President.

And enough, as I realized still later, to change the world.

Four Blasts

YOU CAN TRACE the whole story of Ronald Reagan’s victory in the Cold War, I now see, by looking at just four of his speeches. In the first of the four, delivered to the British Parliament on June 8, 1982, Reagan laid out his strategy for exploiting Soviet economic weakness.

In an ironic sense Karl Marx was right. We are witnessing today a great revolutionary crisis, a crisis where the demands of the economic order are conflicting directly with those of the political order. But the crisis is happening not in the free, non-Marxist West, but in the home of Marxist-Leninism, the Soviet Union….

The dimensions of this failure are astounding: A country which employs one-fifth of its population in agriculture is unable to feed its own people. Were it not for the private sector, the tiny private sector tolerated in Soviet agriculture, the country might be on the brink of famine…. Overcentralized, with little or no incentives, year after year the Soviet system pours its best resources into the making of instruments of destruction. The constant shrinkage of economic growth combined with the growth of military production is putting a heavy strain on the Soviet people. What we see here is a political structure that no longer corresponds to its economic base, a society where productive forces are hampered by political ones…. [T]he march of freedom and democracy…will leave Marxism-Leninism on the ash heap of history….

The Soviet Union facing a crisis? Communism destined for the ash heap of history? Still trying to complete my doomed novel, I was in London the day Reagan delivered this speech. It represented such an affront to all the old, settled notions of coexistence that none of my English friends could quite believe their ears.

Having laid out the economic case against Communism, Reagan laid out the moral case, speaking on March 8, 1983, to the National Association of Evangelicals in Orlando, Florida.

Yes, let us pray for the salvation of all of those who live in that totalitarian darkness—pray they will discover the joy of knowing God. But until they do, let us be aware that while they preach the supremacy of the state, declare its omnipotence over individual man, and predict its eventual domination of all peoples on the earth, they are the focus of evil in the modern world….

You know, I’ve always believed that old Screwtape [the demon in C.S. Lewis’s book The Screwtape Letters, Screwtape was always trying to find new ways of corrupting human beings] reserved his best efforts for those of you in the church. So, in your discussions of the nuclear freeze proposals, I urge you to beware the temptation of pride—the temptation of blithely declaring yourselves above it all and labeling both sides equally at fault, to ignore the facts of history and the aggressive impulses of an evil empire, to simply call the arms race a giant misunderstanding and thereby remove yourself from the struggle between right and wrong and good and evil.

The Soviet Union, an evil empire. By the time Reagan delivered this speech I’d joined the staff of Vice President Bush, where, courtesy of the American taxpayer, I found three newspapers a day and about half a dozen magazines a week delivered to my office. I discovered that for months—literally months—I could count on seeing that phrase, “evil empire,” referred to in a newspaper or magazine at least once or twice a week. National Review and the Wall Street Journal applauded it. Nearly every other publication denounced it. But the phrase continued to echo.

Reagan delivered the third speech on June 12, 1987, in Berlin. By then the Soviets found themselves on the defensive, less intent on expanding abroad than on reforming at home. Speaking at the Berlin Wall, the Brandenburg Gate rising behind him, Reagan responded to Mikhail Gorbachev’s new policies of perestroika, or reform, and glasnost, or openness.

We hear much from Moscow about a new policy of reform and openness. Some political prisoners have been released. Certain foreign news broadcasts are no longer being jammed. Some economic enterprises have been permitted to operate with greater freedom from state control. Are these the beginnings of profound changes in the Soviet Union? Or are they token gestures, intended to raise false hopes in the West or to strengthen the Soviet system without changing it…? There is one sign the Soviets can make that would be unmistakable….

General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization, come here to this gate.

Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate!

Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!

Like the phrase “evil empire,” the phrase “tear down this wall” echoed for months.

The last of the four speeches took place on May 31, 1988, during Reagan’s visit to Moscow. Standing beneath a gigantic marble bust of Lenin, Reagan addressed several hundred students at Moscow State University.

Freedom is the right to question and change the established way of doing things. It is the continuing revolution of the marketplace. It is the understanding that allows us to recognize shortcomings and seek solutions. It is the right to put forth an idea, scoffed at by the experts, and watch it catch fire among the people. It is the right to follow your dream, or stick to your conscience, even if you’re the only one in a sea of doubters.

Freedom is the recognition that no single person, no single authority of government has a monopoly on the truth, but that every individual life is infinitely precious, that every one of us put on this world has been put there for a reason and has something to offer.

The fortieth President, describing freedom to the children of the Soviet apparat. The Cold War was over.

In London, Reagan announced his strategy for dealing with the Soviets; in Orlando, he made the moral case for pursuing it; in Berlin, he pressed his advantage over the Soviets, who were by then on the defensive; and, in Moscow, he gave a victory speech in which, instead of gloating, he extolled the ideal of liberty.

What strikes me as I reread these four speeches is that each shared the same penetrating, trumpetlike quality as Reagan’s 1964 speech for Barry Goldwater. The diplomacy of coexistence and détente, the moral relativism that recognized no real difference between the Soviet Union and the United States, the view that we should manage geopolitical reality rather than transform it—the speeches pierced these old, settled notions the way a trumpet blast pierces din.

This raises a question. You see, although Ronald Reagan wrote that speech on behalf of Barry Goldwater, speechwriters drafted the other four: Tony Dolan wrote the address to the British Parliament and the “evil empire” speech, Josh Gilder the address at Moscow State University, and I myself the speech in the middle, the address in Berlin. How was Reagan able to go right on sounding like Reagan even when other people were composing his words?

For a long time the question puzzled me. I know. It doesn’t make sense. I can only tell you it didn’t make sense at the time, eit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- PROLOGUE

- One: THE PONY IN THE DUNG HEAP

- Two: THE POSTHOLE DIGGER

- Three: HOW TO ACT

- Four: TEAR DOWN THIS WALL

- Five: AT THE BIG DESK IN THE MASTER BEDROOM

- Six: THE MAN WITH THE NATURAL SWING

- Seven: WITHOUT HER, NO PLACE

- Eight: THE OAK- WALLED CATHEDRAL

- Nine: TOMFOOLS

- Ten: THE LIFEGUARD VS. KARL MARX

- EPILOGUE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- About the Author

- Books by Peter Robinson

- Copyright

- About the Publisher