![]()

C H A P T E R O N E

Standing Up for Principle

You gain strength, courage, and confidence by every experience in which you really stop to look fear in the face. You are able to say, “I lived through this horror. I can take the next thing that comes along.” . . . You must do the thing you think you cannot do.

—Eleanor Roosevelt

Like most private schools, St. Paul’s School for Boys posts athletic schedules on its Web site. In the spring of 2001, it listed baseball games, tennis matches, and crew events on its leafy campus in suburban Baltimore. But not lacrosse. Not that spring. Despite being ranked number one in a nationwide lacrosse poll earlier in the year, this prestigious 151-year-old institution canceled its entire varsity season on April 3.

The reason? Earlier in the spring, a sixteen-year-old member of the lacrosse team had a sexual encounter with a fifteen-year-old girl from another private school—and, without her knowledge, videotaped the whole thing. He was apparently mimicking a sequence in American Pie (a movie some of the students had recently seen) in which a character broadcasts a live sexual encounter on the Web. When his teammates gathered at another player’s home to look at what they thought would be game tapes of an upcoming rival, they saw his video instead.

None of the teammates objected. Nobody tried to stop the showing. Instead, they watched.

What happened next is a tale of moral courage—a lack of it among teammates who failed to stand up against the video, and the expression of it by an administration that took a formidable public stand. Their debate was a wrenching one. At St. Paul’s, lacrosse has a sixty-year history. It garners solid alumni support, which translates into funding. And it attracts some of the best young players in the region—so many that St. Paul’s runs the risk of being seen, as one administrator put it, as “a ‘jocks rule’ type of school.” But its students are still required to attend chapel. As an institution affiliated with the Episcopal Church, it retains a serious tradition of ethical concern. And it seeks to be a private community dedicated to serious education in a very public world.

What do you do when a popular sport crosses swords with an ethical collapse? In this case, the answer was clear. The headmaster, Robert W. Hallett, stepped in immediately, asking not only (as some who were there recall), “What happened to our school?” but more particularly, “What happened to this young woman?” The boy who made the video was expelled. Thirty varsity players were suspended for three days and sent to counseling with the school’s chaplain and psychologist. Eight junior varsity players were made to sit out the rest of the season. And the varsity season was terminated.

“At a minimum,” Hallett wrote to parents, “we should expect each boy here will, in the future, have the courage to stand up for, to quote the Lower School prayer, ‘The hard right against the easy wrong.’ ”

He might well have been speaking for his own administration. Choosing the “right” was, in fact, hard. It meant disappointing parents, students, alumni, and national lacrosse fans. It meant facing a spectrum of criticism that ran all the way from “You made a mountain out of a molehill!” to “You let them off too easily!” It put at risk an array of crucial relationships with donors and friends, religious affiliates, advisers and counselors recommending the school to potential enrollees, and the entire Baltimore community. It set in motion a pattern of events that might have either plunged the offending students into deep reflection and self-improvement or pushed them out of the educational arena altogether. And it brought the young woman, who remains anonymous, into the center of a national story over an incident she wanted to put behind her.

Moral courage doesn’t always produce an immediate benefit. In this case, however, it did. The student at the center of the controversy later graduated from a local public school. The young woman moved out of state and continued her education. Both appear to have landed on their feet. Hallett, who moved on to an executive position outside education, was swamped with letters praising his stand, which he kept, and requests for interviews on national television, which he turned down. And in the months following the decision, St. Paul’s found that requests for admissions materials actually increased, and that a smattering of financial gifts arrived from new donors far beyond the Baltimore community who wanted to express their gratitude.

Standing up for values is the defining feature of moral courage. But having values is different from living by values—as the twenty-first century is rapidly learning. The U.S. soldiers who abused Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison, the CEO of Italian food giant Parmalat who kept quiet as financial malfeasance proliferated, the Olympic athletes who succumbed to steroids, the American president who deceived the world about his sexual escapades—these were not horned and forktailed devils utterly devoid of values. Yet in moments of moral consequence they failed to act with integrity. Why? Because they lacked the moral courage that lifts values from the theoretical to the practical and carries us beyond ethical reasoning into principled action. In the defining moments of our lives—whether as a student watching a videotape or a president facing a nation—values count for little without the willingness to put them into practice. Without moral courage, our brightest virtues rust from lack of use. With it, we build piece by piece a more ethical world.

S H A R I N G T H E

Q U A R T E R L O A F

Juan Julio Wicht doesn’t look like a hero. He never intended to be a player in a high-stakes global tragedy. A researcher at Peru’s University of the Pacific, this soft-spoken priest had been studying national policy issues when he was invited to a gala event at the Japanese embassy in Lima. He thought of himself as a kind of poor academic cousin to the glittering guest list of government ministers, ambassadors, military officers, and business executives assembled there on December 17, 1996.

That was the night that members of the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement shot their way into the embassy grounds. Rounding up the guests crowded around sumptuous buffets, they ended up holding more than four hundred prisoners—the largest hostage taking in history. Dr. Wicht was among them. Speaking to a group of us in Mexico City following his release, he observed that “there are no words to describe” what went on during that siege. It lasted more than four months. Early on, as the guerrillas sought to reduce their captive population to manageable numbers, they offered him, as a man of the cloth, the opportunity to leave. But as a man of the cloth he refused, choosing instead to remain inside until it was over.

What kept him there? What was it that overcame the natural human impulse for freedom, causing him to put some higher principle ahead of his own needs and opportunities for survival? The ethics of his vocation had something to do with it. But to hear him recount his tale, he was even more committed to staying after seeing a simple demonstration of collective moral courage among his fellow captives during their first days together.

Those days, he recalled, were especially intense. The guerrillas were inundated with hostages. There was no food, no place to lie down. Tightly packed into once-lavish embassy rooms, the prisoners squatted together for hours on end. Not wanting to appear to negotiate with the terrorists, the Peruvian government maintained silence. The guerrillas grew increasingly threatening, telling the hostages they would never see their families again. No one knew whether they would eat another meal.

And then someone in Wicht’s crowded room found several small loaves of bread. The group calculated how many mouths there were to feed. Slicing carefully, they gave each person a quarter of a loaf. But just after the pieces had been distributed, a newcomer—an ambassador—was shoved in from another room. Without hesitating, one of the hostages divided his already small quarter loaf in half and shared it with his new fellow captive.

In theory, of course, that’s not supposed to happen. According to popular interpretations of economics and values, individuals under pressure don’t act that way. Humans, we are told, are primarily self-interested. As competition increases for scarce resources, the commitment to such moral values as compassion and sharing goes out the window. In such cases, we’re assured, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs takes over, insisting that our priorities can be reduced to four words: food first, ethics later. So even in a hostage taking, would someone share what might be his or her last loaf of bread? Of course not. To think otherwise is simply naive.

Yet “in that entire experience,” Wicht recalled, “I didn’t see one sign of selfishness.” Was that because all these people were already friends? Hardly. They came from different backgrounds and a variety of countries. “What did we have in common?” he asked rhetorically. His answer was elegantly simple: “We were human beings, and solidarity developed among us.” And out of that solidarity—a commonality of values that put something above their own needs—a collective moral courage rose to the surface that put life itself at risk so that others could live.

T E S T I N G T H E

C O R P O R A T E M E T T L E

Eric Duckworth, an ebullient Englishman with an impish wit, notes with self-deprecating modesty that where moral courage is concerned he “usually fails.” But “on one occasion when I was young and idealistic,” he recalls, “I succeeded—and have been proud of it ever since.”

In 1949 Duckworth and his wife were newly married and applying for a mortgage to buy their first home in suburban London. A metallurgist by training, he had joined the Glacier Metal Company, now part of Federal Mogul, a firm that specialized in making bearings for internal combustion engines. Among his tasks were examining damaged bearings returned by customers to determine the causes of the failures, reporting back to the customers, and if necessary recommending changes in production processes to correct the problem.

Most of the time, he recalls, the failures were due to problems such as misuse, improper installation, and lack of lubrication. But “very occasionally,” he says, Glacier had supplied a faulty part. As Duckworth got more experience, he came to understand that those occasional faults were not being accurately reported. His boss, the chief metallurgist, regularly tried to cover up such faults by refusing to divulge all the facts. “He salved his conscience,” Duckworth recalls, “by saying that he was prepared to commit sins of omission but not of commission.”

As a result, bearing failures for which Glacier should have taken responsibility were attributed to mishandling by the end users, and no effort was made to compensate customers.

“After a while,” says Duckworth, “I disagreed.” He had been with the company for only six months when a particularly egregious case of failure by Glacier came to his attention. Instead of shifting the blame, he “wrote the report with complete honesty.” When his boss rejected his findings, Duckworth recalls that “in my altruistic, youthful fervor, I said I would resign.”

Moral courage or rash bravado? At the time, says Duckworth, “It was very foolish of me.” The sales department, agreeing with the chief metallurgist, protested his report vigorously, certain that such an admission of mistakes would cost them this customer and perhaps many more. Fortunately, Duckworth had already made suggestions that had increased the productivity of the manufacturing line threefold. Those actions, he suspects, had won him the admiration of the CEO, who backed him against his boss. The report was sent to the customer.

Shortly afterward, Duckworth says, “we got back a very congratulatory letter saying that the customer had always suspected concealment in some of our reports.” Welcoming the company’s newfound candor, they increased their orders as a result.

T H E C O M M O N T H R E A D S

O F C O U R A G E

These three stories—of exploitation in Baltimore, terrorism in Lima, and dishonesty in London—would seem to have little in common. The first happened amid suburban comfort, where the risks were shame, suspension, or expulsion. The second happened at gunpoint, where death was the threat. The third happened in the corporate world, where a career was at stake. One made the local and national papers. Another occurred below the radar during an incident that drew glaring global publicity. The last never reached print until now.

Moral courage comes in a palette of colors. It happens to people who may or may not have any notoriety. Yet it happens in a social context that includes morally courageous actors and—in these three cases, although not always—a supporting cast of others who also exhibit moral courage. Hallett’s faculty at St. Paul’s, Wicht’s fellow captives in Peru, and Duckworth’s CEO all resonated to the sound of moral courage, making it easier for the actor to display the courage needed in the moment.

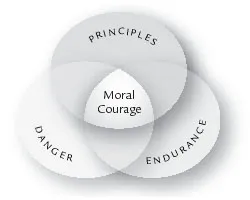

And through each of these tales runs the three-stranded braid that defines morally courageous action: a commitment to moral principles, an awareness of the danger involved in supporting those principles, and a willing endurance of that danger. Think of these three as intersecting domains:

Figure 1. The Three Elements of Moral Courage

Notice how these relationships play out in these three stories:

| • | At St. Paul’s School for Boys the principles involved an expectation of responsible sexual attitudes and behaviors. The danger Hallett and his staff faced had to do with parental wrath and financial hardship. The endurance arose in their collective stand for the “hard right.” |

| • | At the Japanese embassy in Peru the principles centered on compassion and responsibility. The danger Wicht faced had to do with pain and discomfort, perhaps even death. The endurance arose in his commitment to be present to help even when he himself might be rendered helpless. |

| • | At the Glacier Metal Company the principles centered on honesty and fairness. The danger facing Duckworth concerned unemployment and self-condemnation. The endurance arose in his willingness—due to a clear understanding of values, youthful chutzpah, or something in between—to risk the full consequences of that danger. |

D E F I N I N G CO U R A G E

Most definitions of courage put it at the intersection of the two bottom circles, danger and endurance. According to the third edition of Webster’s New International Dictionary, courage is “that quality of mind which enables one to encounter danger and difficulties with firmness, or without fear, or fainting of heart.” That definition may be overwrought in using the phrase “without fear”: John Wayne’s comment that “courage is being scared to death—and saddling up anyway” reflects a recognition, common throughout the literature on courage, that the greatest courage may in fact arise in moments of the greatest fear.

More usefully, the same dictionary cites a simpler definition of courage by General William T. Sherman (after whom the Sherman tank is named) as “a perfect sensibility of the measure of danger and a mental willingness to endure it.” Courage, as those two bottom circles suggest, is all about assessing risks and standing up to the hardships they may bring.

In common with other core attributes of humanity, courage is not peculiar to Western culture nor the modern age. Courage, notes the British intellectual Isaiah Berlin, “has, so far as we can tell, been admired in every society known to us.” In our modern usage, however, courage typically subdivides into two strands, which we tend to describe as physical and moral.

Physical courage has to do with the guts to climb up one rock face or rappel down another, the valor to continue running uphill into enemy fire, or the bravery of a mother plucking a drowning child from the surf. For each of these acts, the word courage easily springs to mind. We make no requirement that these acts be related to principles, values, or higher-order beliefs in “doing the right thing.” On some occasions, to be sure, physical courage may be driven by a sense of honor. It can be shaped by a concern over reputation. It can even be enhanced by a recognition that good things will come by being bold. But while physical courage may be principle-related, we don’t require that it be principle-driven.

Moral courage, however, is just that: driven by principle. When courage is manifested in the service of our values—when it is done not only to demonstrate physical prowess or save lives but also to support virtues and sustain core principles—we tend to use the term moral courage. Moral courage is not only about facing physical challenges that could harm your body—it’s about facing mental challenges that could wreck your reputation and emotional well-being, your adherence to conscience, your self-esteem, your bank account, your health. If physical courage acts in support of the tangible, moral courage protects the less tangible. It’s not property but principles, not valuables but virtues, not physics but metaphysics that moral courage rises to defend. Where the physically courageous individual may be in full agreement with the momentum of the occasion and is often bolstered with cheers of encouragement and team spirit, the mo...