AS I WRITE THESE WORDS, MY NINETIETH BIRTHDAY LIES over the horizon. It is hardly unusual to encounter a ninety-year-old today. Nor does it feel “unusual” to be ninety. When I look out, my eyes take in what anybody would see. But once…. No, let us begin properly: Once upon a time, long ago and far away, there was a boy who saw a world no one will see the likes of again.

When I compare my childhood to a boy’s or girl’s today, I realize, in retrospect, that mine took place in a garden of never-agains. Probably never again: shall a boy grow up so isolated from the bigger world, in a place so self-contained that it made its own little world. Probably never again: shall a child’s days be so simple. (I could not petulantly pout, “Don’t want this—want that!” because there was only this and no that.) Probably never again: shall opposites—life and death, rich and poor—be so close as to seem two sides of the same coin. And surely never again: shall existence be so uncluttered by technology, so gadget-and distraction-free. Every sound I heard was natural or human-made. Ours was basic Life 101.

My early memories might be pictures in a medieval manuscript rather than belonging to someone still living in the twenty-first century. My childhood took place in rural China, and indeed the town where my parents were missionaries had a medieval wall around it. At ten at night the town gates were locked, to keep out thieves, and the town crier beat his bamboo stick against a gong—gwang, gwang, gwang—to scare off robbers. Within the town wall nothing—in a way not even our body parts and body functions—resembled its counterpart today. Our amah, or nanny, had “golden lotuses,” those bound feet so prized (by men) in old China. I recall watching, with horror and fascination, her unwrapping the horrid, smelly bandages from her feet each evening. Inside our home we had no flush toilet; rather, a “night-soil harvester” carted away our bowel movements for fertilizer, leaving us in exchange a few small coins. The town wall kept out not only thieves and robbers; it shut out almost everything you would be familiar with today, which in any case had not been invented or simply was not available there.

It was a self-contained world. In our small town, named Dzang Zok, no movies, television—much less the Internet—existed to bring the faraway near. There were no telephones whose ringing would have inserted elsewhere into here. By the time a newspaper finally reached us, its news was history. If we eventually had a sort of radio, it was because my clever older brother built his own crystal wireless set. It received a grand total of one station, broadcast from Shanghai, sixty-five miles away. When we called our amah in to listen to it, she circled it, wary of the demon inside the contraption. It was easier to believe that a hidden sprite was talking than that a box could.

Except for that radio, no traffic, no automobiles, no sirens, no planes overhead intruded; not even a dentist’s drill hummed. There was little in the way of machinery or technology in the town: our coal-stoked generator provided our house with the only electricity in the area. With no other electric lights and also with no pollution in rural China then, from our backyard I gazed at the same night sky a hermit on a Himalayan mountaintop might see, infinitely star-lit and glittering.

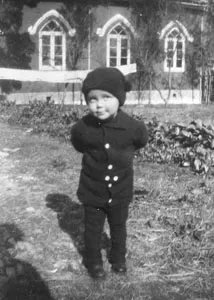

The youngest churchgoer in China. I am standing outside my father’s church in Dzang Zok. Soon I would start my own church—in our toolshed: I played minister and the neighborhood Chinese boys and girls were my parishioners.

As an adult, after living in America, I returned to China on a visit. I tentatively asked the elevator man in our Shanghai hotel if my Chinese was still understandable. When he nodded, I explained, since I spoke not in a Mandarin but a Shanghai dialect, “I am a Shanghai man.”

“Noooo!” he said.

I then named the city nearer to the town where I grew up. “I am a Soochow man.”

“Nooooooooo!”

He shook a finger at me. “You are Dzang Zok man!” The globe today is one interconnected overlapping network, but my accent still marked me from one tiny dot, Dzang Zok, which in my boyhood was the whole world.

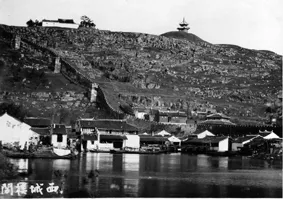

The town of long ago and far away. Dzang Zok was in many ways more a town of the Middle Ages than one of today. You can just make out part of the medieval wall that encircled the town.

Within that small world there was a smaller world. We were the only Caucasian family in Dzang Zok, practically a law unto ourselves. My father was every (white) father; my mother, every mother. I knew only one way things could be. I did not wonder whether to become a fireman, baseball player, or president when I grew up; only one profession was imaginable: missionary. Going from home to school was not the shock of strangeness many six-year-olds feel; for me it meant walking to the dining-room table, where my mother taught me and my two brothers. I can remember my very first lesson. Mother described a blind man who, bumping into a tree, asked what it was. Upon being told a tree, he said, “I see.” I wrote down my first words: I SEE. My mother taught with such gentleness that I never realized I was an agonizingly slow learner. Had I gone to a public school, and not received the attention she lavished, I might have been segregated into a class for “special” children.

The tower that dominated our town. All such towers have seven stories to represent the seven heavens and a roof to ward off the rain.

And opposites and contraries were neighbors there. Death was too common in Dzang Zok to be hidden away. My parents’ first child, Moreland, died on his second Christmas Eve. Our male cook’s son died in the night, and I remember thinking it strange to see a man weeping. An irrepressible, high-spirited missionary visited us, and the next day he ate contaminated food and died. My parents grieved for Moreland; our cook grieved for his male baby; I grieved for the fun-loving missionary. My earliest memory is of the precariousness of life—of being on fire with a raging fever, when I was rationed to one teaspoonful of boiled water every forty-five minutes, for that was all I could keep down. What’s different (from now), however, is that though people suffered and grieved, they did not live in fear of the Dark Stranger. Death was not a thing apart, an “unnatural” tragedy, nor for the religious was it even the end of the story.

If life and death existed side by side, so did rich and poor. Which were we? Neither. Both. We had a half dozen servants, including one who “mowed” the lawn with scissors. But my parents never stopped working, knew no leisure, had no luxuries. We were like millionaires without money. When my older brother, Robert, went away to school in Shanghai, my father, realizing that haircuts cost money in the city, prudently shaved off all Robert’s hair, to save twenty-five cents. (It earned my brother the unfortunate nickname “Sing-Sing,” after shaved-headed convicts in that penitentiary.)

The elements were our neighbors. If we had water, it was because my father dug a well. Having grown up on a Missouri farm, my father had learned to raise, tend, and build everything needed, and he continued to so in Dzang Zok. We had to boil the well water for twenty minutes and then filter it though a cloth before we drank it. If we tasted sweetness, it was because my father kept honeybees. If we could read and write, it was because my mother taught us how. Children in America at that time, after the Lindbergh kidnapping, feared suspicious-looking strangers. My fears were more basic. I feared the wild dogs in the street. (One visiting missionary advised, “Throw charcoal—not a rock—at them; bursting, it scares the curs away.”) I feared cholera. Before a trip I still find myself drinking glass after glass of water: you never know—as the saying goes—where your next drink will come from. Mine was an earthy childhood, but its earth was close to heaven. Without the clutter of many things, with few distractions (no television, computer games, and so on), not hemmed in with scheduled activities, a subtle, almost transcendent sense of something else, the lovely undertone of just being, made itself felt.

In an imaginary scrapbook, as I turn again the pages of my childhood, most of the “snapshots” or memories are happy ones. And in them a lost China lives once more. I look up, transfixed, at dragon kites—six or eight round paper disks strung loosely together—undulating in the blue sky. I steal off to play as my Chinese tutor dozes off, muttering, “Write a bit more clearly.” I climb into the porcelain tub and feel the delicious shock of the hot water, heated on the stove for our Saturday-night weekly baths. At Christmas I carry red paper lanterns, three on each outstretched arm, to give to father’s parishioners. The lanterns have “Jesus Christ” painted in Chinese characters on one side and “Birthday” on the other. When the lanterns are delivered, we hurry to the Christmas Eve pageant in the church, where girls from my father’s school sing a carol in English to impress their parents. However, Chinese children have difficulty pronouncing our R, so it comes out, “Ling the melly, melly Clismas bells; ling them fah and neah.” It all feels so palpable, as though there were a door somewhere and I could reenter that lost world of wonder. Well, this book, I suppose, is that door.

Yet I am sometimes told (by people who were not there) that it could not have been a happy childhood. Your parents (they point out) were missionaries, blind to the indigenous culture. They were also fundamentalists, abstainers, prudes. That is partially true. I never saw my father in less than a full suit of underwear that covered every inch of his body from throat to ankles, hands excluded. My mother could not bring herself to say the Chinese word dung, though it does not refer to excrement. She would drop the g, so that no Chinese had a clue what she was talking about. And yet…I am tempted to respond: no one under the age of maybe a hundred—but at the youngest sixty—has any idea what it was to be a missionary then. So let me tell you what my father and mother were really like.

A slogan thrilled my father that would chill many people today. Let Us Christianize the Whole World in One Generation was the motto of the Christian Volunteer Movement as the twentieth century began. It stirred my father’s youthful idealism. His given name was Wesley, and a more Methodist name there cannot be. Like the original John Wesley, who traveled two hundred and fifty thousand miles on horseback and delivered forty thousand sermons, establishing charities and bringing salvation to the downtrodden, my father, who bore his name, would do the same work, on a smaller scale. He, too, would glorify God and serve man, even if at first he was not sure how to.

When my father was a student at Vanderbilt University, a recruiter from the Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions spoke there. The recruiter took out a pocket watch and began counting off the seconds, but what he was really counting, he said, were the souls who, second by second, were sinking into perdition. This avalanche of lost souls were the unfortunate millions in China who would never hear the word of Christ preached to them. The recruiter paused for effect and then rang out, “Who will go to Asia? Who will give all, do all, be all to save the lost souls of China?” Wesley Smith’s hand shot up.

The board of missionaries assigned my father to Soochow, where he taught at the Methodist university until he learned Chinese sufficiently to do true missionary work. In 1910 in Soochow he met a young woman named Alice Longden. A missionary’s daughter, Alice had grown up in China, almost next door to the Nobel Prize-winning author Pearl Buck, whose novels spelled the romance of China for my generation. Alice was then teaching young Chinese women the piano, so they could accompany the hymn singing in church—exactly as her mother had done before her. Alice was a single female Methodist in China (of which there were not many); Wesley was a single male Methodist missionary in China (of which there were not many). Methodist missionaries should not be single. Given a similar circumscribed choice, Adam and Eve had also paired off. Alice Longden and John Wesley’s marriage was to have happy consequences and—to jump ahead of the story—I was the middle one, in between my older brother, Robert, and my younger brother, Walt.

Preach the gospel where it has never been heard. That idealism inspired my parents to move to missionary-less Dzang Zok, an arduous journey first by train and then by canal boat from Shanghai. My parents were so young then, the age my grandchildren are now: I marvel at their innocence, their courage. Moving to Dzang Zok cut them off from everyone who shared their heritage, removed them from anyone who could understand them, left them among people who spoke no English. And without thinking twice they decided: perfect. But what did they actually do, once in Dzang Zok? The short answer is “the good.” A foundling was left at their doorstep, so they started an orphanage. They saw people starving, so they started a soup kitchen. Girls received no education, so my father began a girls’ school. Since they wanted their children to have smallpox vaccinations, the Chinese boys and girls should have them, too: my parents personally inoculated all the town’s children, risking exposure to the disease themselves. All this was good, but for my parents there was still the greater good to do, which was preaching Christ’s love and living it out in th...