![]()

Chapter I

The Levantine Waterway, Riparian Archaeology, Paleolimnology, and Conservation

Dov F. Por

Department of Evolution, Systematics and Ecology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 91904 Jerusalem, Israel

Abstract

The Levantine aquatic corridor is the product of the ongoing rifting process in the Middle East. A “stepping-stone” chain of longitudinal river basins in the basically arid Levant probably served as a precondition for human expansion out of Africa. It has likely been a duplication of the expansion of the aquatic biota in these freshwater enclaves. Tectonics, volcanism, and paleolimnologic events were coeval with the different waves of Levantine settlers. Attention is given to the lakes and rivers, but first of all to the chain of strong artesian springs which functioned permanently despite fluctuating Pleistocene climatic conditions. The sequence of the Jordan-Litani-Orontes Basins is fed and maintained by such springs. The very narrow and discontinuous Mediterranean coastal plain, especially north of Haifa, could not serve as an alternative route. The role of spring-fed marshlands is especially evident in the case of the riparian Natufian settlements and the early stages of cultivation. Preservation and restoration of such sites that are not yet disturbed is urgently needed for documentation and research of both biodiversity and archaeology.

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to shed light on the importance of the limnological environmental setting for human prehistory in the Levant. The importance of riparian sites in the Levantine Corridor, the western branch of the Fertile Crescent, for human expansion out of the African cradle became obvious with the discovery in the 1960’s of the Late Pliocene site of Erq el-Ahmar (Stekelis 1960; Tchernov 1975) and the Early Pleistocene localities at ‘Ubeidiya on the Jordan River (Bar-Yosef & Tchernov 1972). There are many other sites, including more modern ones, which underscore the importance of the Dead Sea and Syrian rift valleys in this corridor. Throughout the Pleistocene, the corridor provided propitious conditions for multiple northbound waves of human migration. Epipaleolithic and early Neolithic sites in the Jordan Valley have also shown that very important steps of the transition to sedentary life and to cultivation occurred there. Rather than being merely a connecting passageway, the Levantine Corridor provided a sustained set of suitable habitats for the autochthonous biological and cultural evolution of the waves of African expatriates. Although the majority of known archaeological sites, both Pleistocene and later, are concentrated in the Jordan section of the rift valley, where investigations have taken place since those of Picard (1960) and Perrot (1966), the following discussion will attempt to deal with its entirety.

In the literature, the uplifted parallel Cis- and Trans-rift mountain chains are seen as the principal factor for the southward extension of Mediterranean climate into the Syrian desert (Por 1975). Contained between the two chains, the rift valley itself, at least in its southern part, is known to be the northward extension of tropical “Sudanese” climate, with tropical biota similar to those of the African hominid savanna homeland.

The role of spring-fed oases, rivers, and river-fed water bodies in the graben, which are largely a product of tectonics, has not been sufficiently emphasized (Por 1975; Por & Dimentman 1989). These oases are the “stepping-stones” in a sequence of rivers.

The exorheic (i.e., rivers emptying in the sea) Nile and Euphrates River Basins experienced a very tumultuous hydrographic history related to sea-level fluctuations during the Pleistocene. Consider, for example, the catastrophic rapidity with which the area of the Persian Gulf was reinvaded by the sea during the post-glacial Flandrian transgression, modifying the hydrographic baseline of the Euphrates. The hydrographic story of the Nile and its delta has been even more unstable, as this river often turned into a huge seasonal stream. While both river systems cross and fertilize major desert regions, they are fed by distant headwaters situated in regions with much higher precipitation. For the hydrographer, these rivers are xenorheic, i.e., “foreign rivers,” in their lower desertic reaches.

In contrast, the much more modest river basins of the Levantine rift valley were largely isolated from the Mediterranean after the termination of the Pliocene marine gulf and the uplifting of the Cis-rift mountain ranges. Since that date, the water bodies of the rift have had a prevalent tendency to be endorheic, i.e., to end up in terminal lakes or in terminal swamps and sabkhas (salt pans) rather than emptying into the sea. Outflow to the Mediterranean was episodic. World sea-level changes did not influence these rivers, which are fed by autochthonous abundant and stable springs (karstic exsurgent outpours) that render them independent of the drainage of the surrounding intermittent mountain torrents and wadis. These are artesian springs that drain ancient aquifers rather than collecting surface runoff. The output of these springs, therefore, shows little variation in response to secular climatic fluctuations. During the Pleistocene of the Levant, ongoing tectonic faulting repeatedly created new or rejuvenated endorheic river basins.

This is a rather unique hydrographic situation, since most rivers of the world are fed by intricate confluent headwaters that start in surface springs situated at high elevations. The output of these springs depends on rainwater runoff or on shallow recent water tables. In the semi-arid climate of the Middle East, the surface springs dry out during the summer or during years of drought and the streams turn into empty wadi beds. If the rivers end up in terminal lakes, these lakes tend either to turn into saline sabkhas or to dry out completely in response to changing pluvial regimes. Quite significantly, the Hebrew name for such ephemeral streams is “nahalei achzav”, i.e., “disappointing streams,” whereas the perennial artesian-fed streams are called “nahalei eitan,” i.e., strong, reliable ones.

Because of this general background of hydrographic homeostasis, a permanent chain of rivers and wetlands was always present during the Pleistocene of the Levant, despite fluctuating sea levels and changing pluvial regimes. This longitudinal chain of oases provided for the existence of a rich variety of ecological resources in the rift valley that might have been particularly attractive to the hominids of the Jordan-Dead Sea rift during Pleistocene times (Werker & Goren-Inbar 2001). Along this western branch of the Fertile Crescent, by taking advantage of the wetlands humans could have expanded in subsequent waves, little influenced by the climatic hardships of the neighboring Syrian desert. Throughout the Pleistocene, the Levantine Corridor experienced a milder microclimate, produced by the lakes and rivers in the rift valley with their local evaporation-precipitation regime.

Because of its lakes and oases, the Levant became the most important passageway for European bird migration to and from Africa. This provided an additional resource for the hunters and trappers of the rift valley. Paradoxically, the crisis times of the full Glacials in Europe, with increased bird migration, were probably years of bounty for the hunters and trap-setters of the Levant Corridor.

The Levantine coastal plain, supplied with sediment from the Nile, is relatively broad in the south, but gets narrower and narrower and practically ceases to exist north of the Gulf of Haifa. There is no “Via Maris” along the Lebanese and Syrian coasts, since the Lebanon and Ansariya Mountains drop off abruptly into the sea. Isolated pockets of lowlands exist only at the mouths of the mountain streams. Nor were broad coastal plains exposed by lowered sea level during Glacial periods, since deep and steep submarine canyons accompany the shore from the western Galilee northward. In addition, as mentioned by Bar-Yosef (1998), the poor and unproductive eastern Mediterranean could not supply sufficient marine foods for large human settlements. There are no kitchen middens on our shores. Like so many armies in the millennia to follow, upon reaching the Carmel promontory, the wave of human settlements had to move inland along the rivers and lakes of the rift valley.

Springs of Eden, rivers of Life

The idea of Paradise has always been associated by the ancient people of the arid Middle East with life-giving springs and rivers. Sura 55 of the Quran identifies Eden as a place with “two springs pouring forth water in continuous abundance.” The biblical Paradise is a place from which four rivers flow out. In the widespread tradition these rivers are the Euphrates, the Tigris, and the unidentified Gihon and Pishon. More precisely, the Arab popular tradition associates Paradise with the rich artesian spring of the Barada River near the foothills of Mount Hermon and with the oasis of el-Ghutta, near Damascus, which is fed by this endorheic river. In more concrete, but still poetic terms, the massif of Mount Hermon, “Jebel esh-Sheikh,” is also called “the Father of the Rivers.” At 2,814 m, it is the highest peak in the region and forms the abruptly ending southern extension of the Anti-Lebanon Range. Unlike its surroundings, the Hermon is built of uplifted Jurassic limestone, a porous karst formation rich in fissures and crevices. Snow-covered for a good part of the year, this mountain was possibly an isolated southernmost point where ephemeral Pleistocene glaciers could develop. Efficiently blocked towards the south by the Golan basalt fields, the Hermon has very little surface runoff and almost all the snow feeds deep karstic aquifers that emerge in the adjacent synclines in the shape of several strong exsurgent vauclusian rivers.

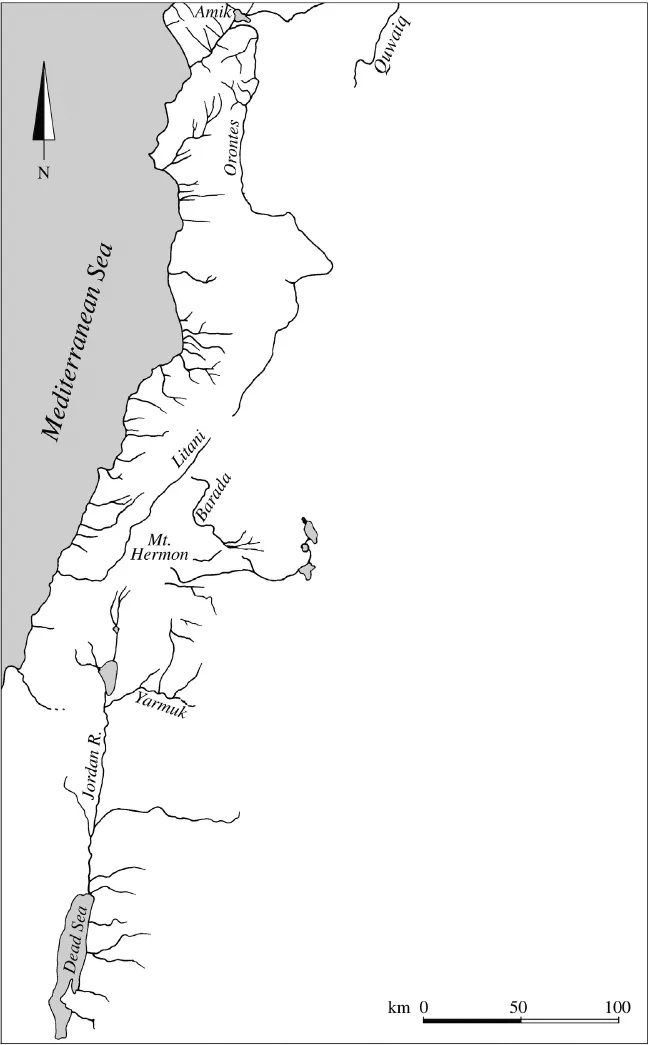

We are dealing with fossil aquifers that accumulated during the last pluvial episodes (Geyh 1994). The headwaters of four main rivers, the Jordan (formed by its three confluent headwaters), the Litani, the Orontes, and the Barada, emerge from the Hermon aquifer in a very small and privileged piedmont area of only about 2,000 square kilometers (Figure 1). Less impressive, the Awaj River, which also flows eastward into the Syrian desert, south of the Barada, can also be added to this list. The existence of the Levantine waterway, formed by the rivers of the rift valley, depends on the headwater springs of the Hermon aquifer. Without the uplifted Jurassic peaks of the Hermon, the Levantine waterway would probably not exist. Though essentially true, this is a somewhat oversimplified statement, since many more and smaller artesian springs emerge along the rift valley itself, especially along the Orontes, and there is also a not negligible input of rainwater. It has been calculated that the Hermon aquifer supplies a total annual volume of around 800 million cubic meters. This represents the environmental baseline of the Levantine Corridor and, for the desert people, the nearest approximation to the idea of Paradise. Neither in the present nor in past arid episodes is it likely that the permanent base flow of these rivers could have been sustained by rainwater runoff from the desert wadis alone. By a rough average estimate, the deep aquifers supply about 50% of the total flow of the main rivers of the Levant. This is enough to maintain a constant flow in these rivers, even during periods of excessive aridity.

Among the rivers of the Levantine Corridor, the hydrology of the Jordan River is the best known. This river results from the union of three headwater streams, all emerging as strong springs fed in different proportions by the Hermon aquifer. First among them, the stream of Nahal Dan is by far the most abundant and stable source. It is a full-fledged river that gushes out from its subterranean course. The Dan alone supplies 50% of the total flow of the upper Jordan. The output of Nahal Dan shows little seasonal fluctuation and little rainfall influence, since it is in fact an emergent subterranean river. Its average annual discharge is an impressive 245 million cubic meters and the multi-annual variation over a twenty-year period was only between a baseline flow of 173 and a maximal flow of 285 million cubic meters. Even today, this discharge can supply more than one-tenth of the water needs of modern Israel. The world-famous exsurgence of Vaucluse in southern France, already known as a natural phenomenon in classical antiquity, has given its name to this whole category of karstic springs. Its discharge is less than twice the volume of the Dan.

Figure 1. A schematic map of the hydrographic network of the Levant.

The Banias, or Nahal Hermon, the second headwater stream of the Jordan, with a medium discharge of 121 million cubic meters, exhibits a multi-annual variation of between 63 and 190 million cubic meters. Finally, the third headwater, the Hasbani, is a river in its own right, as it runs independently for some 50 km before joining the other two source streams of the Jordan. The Hasbani is formed by two artesian springs, the Hasbayyaa and the Wazzani, but on the way collects considerable runoff. With an average yearly output of 138 million cubic meters, its flow varies between a baseline of 52 million cubic meters and a maximum of 236 million cubic meters. The greater variability reflects its increased dependence on fluctuations in regional rainfall over the years.

The united upper Jordan then enters the valley of Lake Hula and its swamps. Before being drained in 1958, the lake occupied some 12–14 square kilometers. The area of the surrounding swamps fluctuated seasonally between 10 and 50 square kilometers. This lake received input from a number of springs, among them the very abundant karstic spring of ‘Eynan (‘Ein Mallaha), with a medium discharge of 20 million cubic meters per year, and with very little seasonal and multi-annual fluctuation. Before being captured for irrigation, it fed a small 3-km-long tributary river (Dimentman et al. 1992). The middle Jordan then descends rapidly through the gorge of Benot Ya‘aqov to reach Lake Kinneret, which is already around 200 m below sea level. The basin of the lake is situated in that segment of the rift valley that was invaded by the Pliocene Mediterranean. Consequently, this segment of the valley still receives springs that drain old saline aquifers. As many, or even most, of the springs that flow into the lake are salty, Lake Kinneret is slightly oligohaline, at the limit of brackish waters. It therefore makes, at best, very poor drinking water. Most important is the spring complex of Tabgha, the classical Heptapegon, which supplies the Kinneret with a fairly stable yearly average output of 20 million cubic meters of a mixture of fresh and salty waters. Another abundant salt-water spring, Maayan Habarbutim, is sub-lacustrine.

As the lower Jordan leaves Lake Kinneret, descending on its meandering course to the Dead Sea, which at present is 417 m below ocean level, it still receives one important freshwater tributary. This is the Yarmuk River, which once contributed a yearly average of 94 million cubic meters to the Jordan. This amounts to almost the other 50% of the water carried by the lower Jordan. The Yarmuk takes its origins from the artesian Muzayrib spring and other smaller springs. It is commonly assumed that the Yarmuk is also fed by the Hermon aquifer, surfacing far to the south, where the cover of the Golan basalt exposes underlying Jurassic rocks. However, the Yarmuk is fed mainly by runoff, since it has a baseline flow of only 13 million cubic meters in the late summer month of September, as compared with 100 million in the rainy month of February.

Farther down the valley, the Jordan and the Dead Sea receive fresh water from the artesian spring of ‘Ein el- Sultan near the site of Jericho and the oasis springs of Ghor es-Safi in the far southeastern corner of the Dead Sea. The Mujib (Arnon) River and the small mountain stream of Wadi Kelt are perennial watercourses. There are several salty springs, like ‘Ein Feshkha, a non-potable oligohaline spring and oasis near the site of Qumran and, on the opposite shore of the Dead Sea, the hot and saline stream of Zarqat Main, the classical Kallirrhoe. But more than anything else, the level of the Dead Sea depends on the inflow of the Jordan and the amount of runoff reaching it from the two bordering mountain escarpments. In addition, torrents coming from the Judean Desert might have been permanent rivers during periods of wetter climate. The ionic composition of the very concentrated brine of the practically lifeless Dead Sea represents in an amplified concentration the ionic relations of the distant Tabgha springs on the shore of Lake Kinneret.

On the eastern slope of Mount Hermon the Barada River, in association with the smaller Awaj River, waters the large oasis of Damascus in Syria. The main source of the Barada is the strong arte...