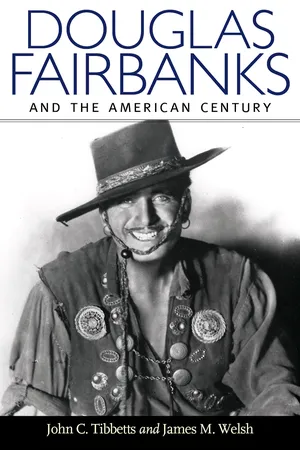

![]()

Part I

ODYSSEY OF A SPRING LAMB

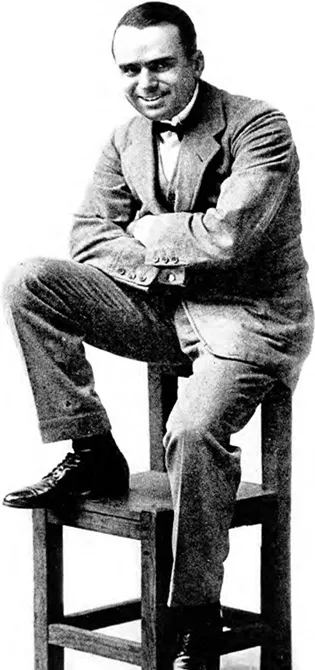

Young Fairbanks ready to take on the movies.

![]()

Chapter 1

“Windows Are the Only Doors”

The First Films (The Lamb, 1915, and Double Trouble, 1915)

In the spring of 1915, Douglas Fairbanks left the New York stage and traveled west to the newly formed Triangle Film Corporation in Los Angeles. On the strength of his credentials as a lively and engaging light comedian, Triangle boss Harry E. Aitken promised him the impressive fee of $2,000 per week, with a $500 increase every six months. The leading director of the day, D. W. Griffith, was to personally supervise all of his films (although this promise was not to be fulfilled). The story of how Fairbanks left a successful career as a light juvenile on the New York legitimate and variety stage for the movies in California is yet to be told in detail. What we have so far has suffered too much hearsay. As recently as Jeffrey Vance’s biography (2008) we still find the tired, oft-repeated anecdote that Fairbanks was spotted one day in Central Park by a motion picture cameraman and, after some mugging for the camera, was contacted by Aitken with a contract offer.1 This is difficult to credit. Surely, Fairbanks had already been eyeing the promise of movies for years and was already known for the sorts of roles he would bring to the screen in the middle-teens. “Instead of the classic roles, I played modern young men,” he recalled in 1922, “young men about town and alert young reporters …” Moreover:

Many of the stage producers with whom he had either worked or known, notably William A. Brady, David Belasco, and Klaw & Erlanger, had themselves been dabbling in film production with an eye to bringing prominent Broadway stars to the screen, and it’s likely that either he or they would have been considering the possibilities.3 Writing in December of 1916, George Creel suggests there had been nothing “accidental” about Fairbanks’s deserting the stage for the movies.

We await further research into this crucial period in Fairbanks’s career.5 For our purposes, suffice it to say, that in just two years, Fairbanks would emerge among the stage stars imported to Triangle as one of the few who would go on to rank as an A-list film star.

What does require our immediate attention here are the first hints on film of the aggressive and mobile Fairbanks masculine persona that he had already crafted with much success on the stage. Although The Lamb and Double Trouble (both 1915) are rarely seen today and languish among his least appreciated efforts, they confront us immediately with what cultural historian Gaylyn Studlar describes as Fairbanks’s “transformative masculinity,” which reconciles several binaries—the working and upper classes, eastern tradition and western promise, and urban and rural contexts.6

The Lamb, directed by Christy Cabanne and “supervised” by D. W. Griffith, was released on September 23, 1915. The precise identity of its source text has proven elusive. The copyright submission of the film declared that its basis was a novel by Granville Warwick (D. W. Griffith) called The Man and the Test. Griffith may have written the film’s scenario, but it is unlikely, according to the AFI Catalogue of Feature Films, 1911–1920, that such a novel was ever published.7 Meanwhile, to further complicate things, the screen credits pronounced Cabanne, not Griffith, the author of the story. Flying in the face of this is an allegation that was first voiced by biographer Ralph Hancock in 1954 and that has surfaced repeatedly ever since: “[The Lamb featured Fairbanks] in the role of Bertie, ‘the lamb,’ which Douglas Fairbanks had played in The New Henrietta on Broadway.”8 Fairbanks did indeed play a character nicknamed “The Lamb” in The New Henrietta in 1913, which justifies Hancock’s comment. “W. H. Crane, Amelia Bingham, Patricia Collinge and I had played in a modernized version of Bronson Howard’s old play, The Henrietta,” confirmed Fairbanks. “Crane acted his familiar role of the owner of the famous mine, and I was Bertie, ‘the lamb.’”9 When examined, however, the parallels between the play and the film are few.

The New Henrietta’s lineage goes back to The Henrietta by Bronson Howard (1842–1908), a four-act comedy-drama of family intrigue on Wall Street, which began its successful run at the Union Square Theater on September 26, 1887. Playwright Howard was much admired by theater historian Montrose Moses as a pioneering champion of a new generation of American playwrights—ranking with contemporaries Clyde Fitch and James A. Herne—devoted to what he called a truly “American Dramatic Literature.”10 As reported by The Bookman, it was a big success in its day:

The plot revolved around efforts by “Bertie” van Alstyne (Stuart Robson) to thwart the attempt by an unscrupulous older brother to destroy the family wealth. The venerable W. H. Crane portrayed Nicholas van Alstyne, the patriarch of the family.

On December 22, 1913, a new, updated version opened on Broadway, retitled The New Henrietta, adapted by Winchell Smith and Victor Mapes. William H. Crane returned to the role of Nicholas van Alstyne, and now Douglas Fairbanks appeared as his son Bertie, “the lamb.” The modern version differed from the original in several respects. The soliloquies and asides of the earlier text were cut, and a contemporary setting including telephones and motorcars was incorporated. A new character, Mark Turner, van Alstyne’s son-in-law, became the villain, while Bertie retained his status of hero. A quick synopsis of the plot confirms how little of the play is present in The Lamb. Nicholas van Alstyne is smitten by the widow Updike. He has a rival, the Reverend Murray Hilton. To get her away from him, he takes her for a cruise on his yacht. Meanwhile, the son-in-law, Turner, tampers with the Henrietta stock. Bertie, who had earlier been given a million dollars and turned loose to sink or swim, finds himself in an important position when his father’s stock is all but declared worthless. Bertie proves himself a man and gives his father a check for all the money he has left. Van Alstyne saves the day and Bertie makes a pile.12

That Bertie’s new characterization was a good thing for Fairbanks is evident in a notice in Theater Magazine a few months later:

The phrases “unctuously humorous” and “overcharged vacuity” uncannily predict the naïve and curious energy that Fairbanks would bring to many of his early films. About the only parallel between the play and the film is that Fairbanks’s character of “Gerald,” like Bertie, is a rich young idler who never had to earn a living but who eventually proves himself to be a man of character and enterprise.14 Fairbanks himself recalled that during the production of The New Henrietta, he had been eyeing the advantages that the film medium held out for his athletic tendencies:

At any rate, after two more Broadway successes in 1914, He Comes up Smiling and The Show Shop, Fairbanks was on his way to Los Angeles to report to Triangle’s Fine Arts Studio, supervised by D. W. Griffith. The Lamb premiered at the Knickerbocker Theater on September 23, 1915, as part of Triangle’s grand plan to unveil its inaugural triple bill, including Thomas Ince’s The Iron Strain and Mack Sennett’s My Valet. The occasion was, according to all accounts, quite spectacular and, according to Motography magazine, the talk of the entertainment world:

Too often, received opinion from historians has held that The Lamb was an “unexpected” hit and that it was a last-minute inclusion in the first program. Gaylyn Studlar, as recently as 1996, reported that “unexpectedly, there was an overwhelming response to The Lamb and to its star.”17 Yet advance publicity made it clear that Fairbanks was among Triangle’s highest-paid performers, and The Lamb was not only regarded as the anchor of the program but also a promising debut for Fairbanks.

For our purposes, as we have suggested, The Lamb marks the first time Fairbanks performed on film what he had already specialized in stage in productions like Hawthorne of the U.S.A. (1914)—a masculine examination of the uniquely American duality of eastern experience/tradition and western promise/freedom. If the film is little known today and of limited interest, however, one might blame in part its quaint, faintly archaic style of diction in the title-writing, which is quite outmoded today. Too little study has been devoted to title-writing and how titles inflected the visual narrative in the silent film. Here, as we shall see, their identification of situations and characters becomes quickly annoying. For example, consider this opening title:

Thankfully, in just a few months, as we shall see in the next chapter, the sharp and satiric scenarist Anita Loos will join the Fairbanks team and save his next films from this sort of floridly rhetorical embarrassment. For the moment, however, the unfortunate practice of archaic capitalizations, generic characterizations, and precious tone was routine. D. W. Griffith was himself particularly guilty of this sort of thing: We think of character labels in Intolerance as “Brown Eyes,” “Princess Beloved,” or, simply, “The Girl.” Later, in The Lamb, we find “Bill Cactus” referred...