![]()

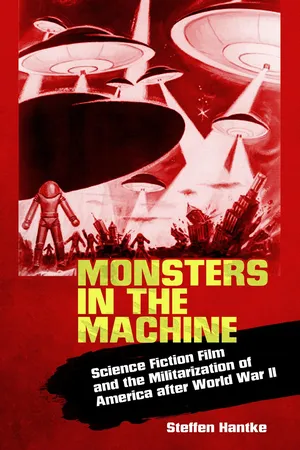

Chapter One

Military Stock Footage

Cinematic Recruitment: How to Mobilize an Audience

In order to tell the story of how 1950s science fiction films helped to mobilize public opinion in favor of the military-industrial complex, it makes sense to look at the beginning of the collaboration between Hollywood and the military. The origins of this collaboration, which are to be found in the propaganda efforts that accompanied World War II, are not interesting because they provide a logistical or economic blueprint upon which postwar film production would be modeled. On the contrary, what they help to show is how postwar efforts would differ from those organized during the war. It stands to reason that patterns and procedures of economics and politics would change as the nation moved from war to peacetime. Nonetheless, it is crucial to elaborate on these differences. To the degree that they help to shed light upon the peculiar, idiosyncratic features of postwar film production, they help to dispel any notions that the dynamic interactions between science fiction film production and the military-industrial complex during the 1950s would have been some sinister conspiratorial plot to bend the nation’s democratic system into service to a ruthless, self-serving economic agenda. As often as Eisenhower’s famous neologism might have been appropriated to paranoid fantasies of one type or another, the differences between film production during and after World War II illustrate that direct governmental influence on artistic creation and industrial production is as much or as little a symptom of the military-industrial complex at work as its absence. So let’s begin the discussion by looking at the production of science fiction and horror films during World War II.

Since science fiction as a clearly defined cinematic genre had not played a significant role on American movie screens before the 1950s, its intersection with the horror film provides the best insight into the prehistory of both genres’ convergence in the 1950s. And as film historian Rick Worland puts it, the horror film had been going through “a dismal decade” during the 1940s (47). Still, World War II had marked a high point in the cooperation between the US military and Hollywood. Created on June 13, 1942, in the wake of America’s entry into the war after Pearl Harbor, the government’s Office of War Information (OWI), aided by its Bureau of Motion Pictures’ Domestic Operations Branch, set out to “‘undertake campaigns to enhance understanding of the war at home and abroad; to coordinate government information activities; and to handle liaison with the press, radio, and motion pictures’” (50). Though the agency had no censorship power, its guidelines stipulated the cinematic explication of America’s engagement in the war. It also managed the politically sensitive handling of nations considered essential allies to the US cause as well as of domestic racial policy and reality (what one might call racial equality under pre-civil rights conditions). All of this was handled by actively encouraging the pursuit of certain themes and storylines. The office’s general power to assess and evaluate whether a film was suitable for foreign distribution carried significant economic clout helpful in enforcing its assessments. Still, “the Bureau of Motion Pictures was never automatically hostile to or particularly worried about the negative propaganda impact of horror films per se” (51). While the British government had instituted a ban on horror films in 1942, no “BMP reviews of horror films decry their violence or morbidity or claim any deleterious effects on civilian morale arising from movie terrors” (51). Regardless of genre, the overriding concern was a film’s adaption to the parameters of mass recruitment to the war effort, both at home and abroad.1 With victory in the Pacific theater, the Office of Wartime Information was dissolved on September 15, 1945. “Hollywood’s extensive cooperation with the federal government in the creation of propaganda messages during World War II,” Rick Worland concludes, “remains historically unique and largely anomalous” (61). In other words, as horror and science fiction films were heading toward the hybrid model typical of the 1950s cycle, direct governmental influence on themes and storylines was already a thing of the past.

If horror film production under the critical eye of the OWI during the war was largely geared toward controlling content rather than actively aiding in production, horror films, with their gothic trappings, inherited largely from the prewar cycle, made few demands on studio budgets.2 Not just in the case of the horror film, budgetary considerations of wartime expediency in the allocation of resources would have been a constraining factor. Even when these budgetary constraints were removed after the end of the war, most horror films did not receive an upgrade to A-picture status. Only with the amalgamation of science fiction with the horror film during the early 1950s did the budgetary demands of the newly hybridized genre increase. This might have been an effect primarily of science fiction, as the genre would demand more ambitious visual special effects.3 Meanwhile, horror films made and released during the war could be aligned with the agenda of wartime propaganda without making explicit references to the war or the military; in fact, Worland cites examples of OWI concerns about the escapist frivolity of horror films clashing with the seriousness of the war and the military as potential backdrops to dramatic storytelling. Only after the war had ended did the presence of war and the military become an essential element in the hybrid genres of horror and science fiction. In order to bring this essential generic element convincingly and, even better, spectacularly to the screen, and to do this in times when governmental support would no longer be easily forthcoming, filmmakers would have to appeal to the military directly. Practically speaking, they would have to ask not for permission but for personnel and material to be lent out and used as extras and props. If World War II had set an example for the cooperation between a state political agenda and the ideological orientation of commercial filmmaking in the US, then the Cold War would reconfigure and bring into focus this cooperation as a facet of what Eisenhower would come to refer to as the military-industrial complex—creating out of necessity an aesthetic that would, in and of itself, carry the power to convince audiences to buy into the Cold War’s perpetual state of crisis.4

Buying into the Cold War: Interpellation Fifties’ Style

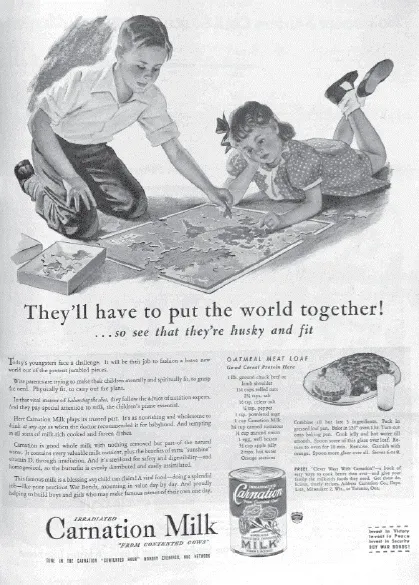

Once World War II would be no longer available as an immediate and obvious reason for the military mobilization of American society, recruitment into a postwar political consensus that accepted not only the continuation but the entrenchment and expansion of the military-industrial complex would be of tantamount importance. This recruitment would have to invalidate all prior assurances that, once America’s enemies had been vanquished, a “peace dividend” would await its citizens. Seeing these efforts of recruitment as a form of “interpellation”—a term I am borrowing from Louis Althusser, describing how individuals are made to accept and conform to ideology in general—requires a specific application of the Althusserian framework. Interpellation, as Althusser puts it, is the process of ideology “hailing” an individual, and thus transforming the individual into a subject; it is a “recruitment” into ideology, a body of ideas which “represents the imaginary relationship of individuals to their real conditions of existence” (Althusser, “Ideology”).

The American Empire: Calling on the Postwar Generation

This application would focus the term specifically on the creation of an individual subjectivity, as well as of a broader cultural consensus, characteristic of America after the end of World War II and in the buildup to the Cold War. First of all, there are specific conditions that apply broadly to bourgeois industrial capitalism. But there are also conditions that apply specifically to the unique configuration of the military-industrial complex and American historical messianism as it was expressed, for example, by Henry Luce’s idea of the “American Century,” the Truman Doctrine, and the Eisenhower Doctrine.5 As the historical reality and its ideological reframing are bound to veer away from each other from time to time, cultural discourses are not only hiding and smoothing over the resulting gaps—a function perhaps most easily associated with ideology. Advertently or inadvertently, they also reveal and draw attention to them, and thus to the fact that the official narrative is essentially an ideological construct. Popular culture at large is engaged in this ideological labor in both functions. It tells the official story, and it undermines that story by revealing its gaps and fractures. Since most science fiction films of the 1950s are keenly aware of themselves as political statements, they signal their topical relevance to their audience. These films, in other words, work hard to make their viewers care—to make them recognize an issue as an issue and apply it as relevant to their own lives. This means that the films ask the audience to pay attention to their grand life-and-death issues, to take them seriously, no matter how preposterous their operating metaphors of alien invaders, fifty-foot women, and giant creatures may be. However egregious their creative overreach, these films are, at their core, deeply serious. In order to be taken seriously, they take great pains to interpellate, to use Althusser’s term, their audience. The more forceful, assertive, persistent, or even desperate their gestures of interpellation, the more fractured the relationship they attempt to construct between the real world and the “imaginary relationships” their audience has with it.

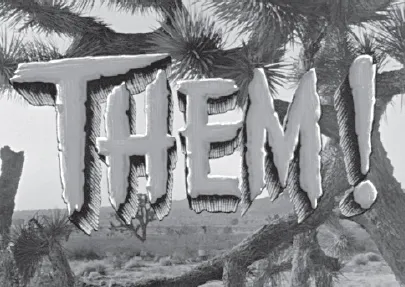

Many science fiction films from the 1950s are associated with B-movie production, and so audience interpellation is largely a matter of strategies and gestures that must work without the benefit of strong production values and against the limitations and inadequacies of the films themselves. In fact, many of these films are loud, garish, and sensational. Whether it is the exclamation mark in a title like Them! (Gordon Douglas, 1954), or the iconic opening titles for It Came from Outer Space (which has a flaming meteor heading directly toward the viewer and crashing, presumably, into the camera lens) and The Thing from Another World (in which the lines of the title are burning themselves through the surface of the title card), or William Castle’s personal appearance at the beginning of The Tingler, the assertive grab for the audience’s attention is an indispensable feature of the genres’ aesthetic repertoire.6 Writing with special emphasis on 1950s films about hypnotism, Kevin Heffernan has pointed out that Castle’s personal appearance and direct address to the audience in the opening of The Tingler (1959) serves as an example of directors delivering—and physically embodying—interpellative gestures. Instructing and guiding the audience, Castle makes a personal appearance before The Tingler gets under way. Together with “Caligari-like figures” like “psychiatrists, carnival barkers, warlocks, and hypnotists,” the director himself, as Heffernan argues, “can be seen as [an emblem] of the forces that mediate between, on the one hand, the horror genre’s eruptions of shock and spectacle, and on the other, the efforts of the narrative both to impel and contain those eruptions” (2000: 61). What Heffernan reads specifically as a regulating function in regard to cinematic genres, I would see as one device in a larger array of strategies aimed at interpellating an audience into a larger ideological system. In this system, cinema serves as a vehicle of delivery for content so important, and yet so complex or ambiguous, that the audience’s proper response cannot be left to chance. Containing and contextualizing “the horror genre’s eruptions of shock and spectacle” is an important function, but more is at stake in that act of containment.

Attention-Grabbers: The Exclamation Point’s Emphatic Urgency

William Castle in The Tingler: Cinema Between the Carnival Tent and the Emergency Broadcast System

Exploding off the Screen: The Opening Credits of It Came from Outer Space

The Opening Credits of The Thing from Another World: Burning Itself into Your Retina

How ubiquitous such gestures of interpellation are for science fiction films of the 1950s also becomes visible in some of the period’s iconic catchphrases and lines of dialogue. The call to caution and vigilance at the end of Christian Nyby’s The Thing from Another World (1951) speaks to the sense of 1950s Cold War paranoia geared toward xenophobic fantasies of invasion and subversion by some hostile alien force. The eponymous Thing has been defeated, and now one of the civilian members of the team broadcasts the news to the world. The important task falls to the journalist who had been prevented from notifying the world of the alien creature below the Arctic ice because of the military’s information lockdown. Surrounded by the rest of the team, he is speaking urgently into a microphone. At the other end of the line is a larger world easily imaginable as the mirror image of the group behind the broadcaster. His words carry such urgency that the details of the dramatic events may be postponed; the warning needs to come first: “Keep watching the skies!” Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) ends on a similar note. When hard evidence corroborates Miles Bennel’s story about alien invasion, Dr. Hill, the psychiatrist, decides to mobilize the authorities. As in The Thing from Another World, explanations are hardly necessary at this point. As demonstrated by the film’s final shot, a medium close-up of Miles Bennel’s face, concerted official action comes as a relief to the tension of prolonged collective ignorance and apathy.

Many of the films in the 1950s sub-cycle of giant creature films also end on a similar note. A strong influence on the US cycle, Ishiro Honda’s Gojiro (1954) assembles in the final scene the military-industrial team that has succeeded in killing off the creature in Tokyo Bay with a weapon even more powerful and terrifying than the nuclear bombs that had awakened it and endowed it with some of its characteristic features. The outstanding senior scientist, Prof. Yamane (Takashi Shimura), having watched his scientific successor sacrifice himself with the deployment of the Oxygen Destroyer, looks into the deep and muses: “I can’t believe that Godzilla was the only surviving member of its species. But if we keep on conducting nuclear tests, it’s possible that another Godzilla might appear somewhere in the world again.” The resonance of this scene is obvious when looking at Gordon Douglas’s Them! (1954), in which a similar figure of scientific authority (Edmund Gwenn) closes the film with the brief monologue. As police officers, soldiers, and scientists incinerate a nest of giant mutated ants in the sewers underneath Los Angeles, Dr. Medford is asked, “If these monsters are the result of the first atomic bomb in 1945, what about all the others that have been exploded since then?” He muses: “Nobody knows, Robert. When man entered the atomic age, he opened a door into a new world. What we’ll eventually find in that new world, nobody can predict.” Considering that the film, right at this moment, cuts to the image of the conflagration below, Douglas seems very much willing to make predictions—and dire ones, at that.

In their blunt directness, these endings clearly perform a rhetorical gesture that functions at various levels. In Gojira, it is obvious that Prof. Yamane’s words anticipate the string of sequels that would make up the franchise in decades to come. In Them!, the final monologue brings the audience into the debate about nuclear testing, this while keeping it visually enthralled to the far more potent scenario of nuclear war. More broadly, however, all those endings, from the ones in giant creature films to the ones in alien invasion films, interpellate the audience into attitudes that seem spontaneous but need constant refreshment and training. Invariably, these are attitudes of permanent vigilance and allegiance to an institutional system of surveillance. It is obvious that behind this system is the 1950s paranoia triggered by fears of an external nuclear attack and internal communist subversion. To the degree that an inflated sense of self-importance, coupled with a lack of self-confidence, and hyper-vigilance are recurring symptoms of this paranoid state of mind, the Cold War explanation captures the hyperbolic intensity of these endings perfectly well. Where the interpretation needs to be amended is in regard to the origins of interpellation in the political rhetoric and propaganda of World War II. Science fiction films in the 1950s extend this rhetoric to the Cold War. Thus, they both create and meet the demand for militarization by insisting on the normalization of the military-industrial complex as part of the postwar American way of life.

What is remarkable about these endings is that they testify to a concern on the part of filmmakers and/or studios that the defeat of the monster or the alien invaders alone will prove insufficient for re-establishing narrative equilibrium. Obviously, stronger measures are needed to achieve such final closure. Some of these measures even violate the fourth wall of conventional Hollywood storytelling; the monologue at the end of The Thing from Another World, for example, seems to be more addressed to the audience in the movie theater than whoever is at the other end of that microphone. True, none of the patriarchal authority figures in these films look directly at the camera as they deliver their interpellative addresses. But it would take but a small step to move from a dramatic monologue to a propagandistic exhortation of the audience. Both the importance of interpellation, and the anxiety over ineffective or insufficient interpellation, surface in these endings, evoking a larger critical debate about “containment” to which I will return later.

The same anxious, somewhat self-doubting drive toward audience interpellation is also at work in the frequent use of framing devices and narrative and expositional prologues. The ending of Invasion of the Body Snatchers is only the second half of a narrative frame which had opened the film with Miles Bennel (Kevin McCarthy) returning to his hometown of Santa Mira. This return to the frame gives Bennel...