eBook - ePub

Lao PDR

Accelerating Structural Transformation for Inclusive Growth

This is a test

Share book

- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lao PDR

Accelerating Structural Transformation for Inclusive Growth

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Lao People's Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) has shown remarkable progress by consistently building itself into a market-oriented economy, with economic growth in 1986-2016 averaging around 6.5% per annum. The rapid and sustained growth brought about changes in the structure of output, but did not alter job composition: resource-based products still dominate in industry, low value-added jobs in services, and 65% of the labor force in agriculture. This country diagnostic study provides comprehensive analysis and identifies promising new drivers of growth which the Lao PDR can develop to diversify its production structure and speed up structural transformation.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Lao PDR an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Lao PDR by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Economic Performance and Key Development Challenges

1.1 Introduction

The Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) is a small landlocked economy endowed with natural resources, such as minerals, hydropower, and forest products, which have all been instrumental in sustaining higher economic growth in the last decade. After the Communist revolution in 1975, the country had a centrally planned economic system. However, economic performance during this era remained subdued and by the beginning of 1986, the state-led development strategy virtually collapsed. With the inception of the New Economic Mechanism (NEM) in 1986 the government came up with various economic and structural reforms that laid the foundation for transition to a market-oriented economy. Since then, the Lao PDR has shown remarkable progress in consistently building itself into a market-oriented economy. Economic growth during 1986–2016 averaged around 6.5% per annum and the size of its gross domestic product (GDP) increased by six times. The strong growth led to a rise in the per capita income from $170 in 1986 to $2,353 in 2016. Poverty incidence based on the national poverty line declined substantially from 46% in 1992 to 23.2% in 2011–2012.

In sustaining the high growth trajectory, resource-based products and increasing volumes of foreign direct investment (FDI) have played a crucial role. The reliance on resource-based products as an engine of growth has no doubt maintained higher growth; however, job opportunities were insufficient because of these products’ capital-intensive nature. At the same time, the high economic growth has not attracted private investments that are large enough to expand job opportunities in other sectors, thus posing a threat to inclusiveness of growth in the medium to long run. Despite higher GDP growth, the Lao PDR in 2017 is still classified as a least developed country (LDC). The challenges ahead would, therefore, be to keep the momentum of high economic growth, attract larger private investment, while also provide decent job opportunities in the manufacturing and more productive services sectors.

The rapid and sustained growth has changed the structure of the output—the share of agriculture in GDP declined while that of services and industry increased. However, this structural change has had little impact in changing the composition of employment. While the industry sector’s contribution to economic growth has increased, it remains dominated by resource-based products and unable to provide job opportunities. As a matter of fact, the share of industry in total employment has rather declined over time. On the other hand, while the services sector has helped increased jobs, its contribution remains low while most of the jobs fall under low value-added services. With only limited jobs created by the industry and services sectors, the low-productivity agriculture sector is left to absorb the majority of the labor force. Overall, there has been little movement from low-productivity to high-productivity sectors and, consequently, most of the labor force is employed in low-productivity sectors.

In 1986, the Government of the Lao PDR embarked upon the NEM. With the implementation of the NEM, the Lao PDR’s economy transformed gradually from being centrally planned to being market-oriented. The reforms introduced under NEM resulted in a domestic economy that was able to integrate gradually into the world. Overall, the opening of the economy has helped achieve higher economic growth and improve the status of the Lao PDR in the international arena. Since the inception of market-oriented policies and economic reforms, the Lao PDR has shown significant progress and has maintained robust economic growth.

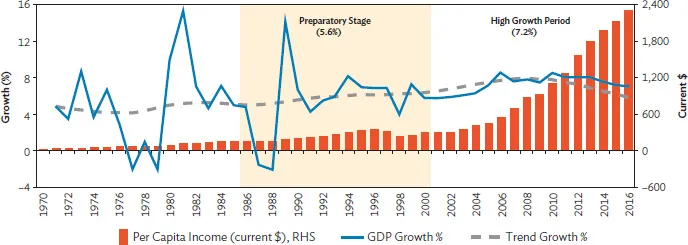

From an analytical point of view, the economic and structural reforms introduced under NEM can be categorized into two stages: a preparatory stage in 1986–2000, and a period of high economic growth in 2000–2016. During the preparatory stage, the reforms aimed to transform the economy gradually into a market-based economic system. To this end, the government introduced various economic and structural reforms, which focused on establishing a legal and institutional framework and maintaining price stability. Prices and production control were deregulated and various incentives provided to develop a vibrant private sector. The government allowed private investment and took measures to attract FDI. In this regard, a law on foreign investment promotion and management in 1988 was passed, allowing 100% foreign ownership of investments. The law was subsequently revised in 1994. Other areas of reforms included improving the agriculture sector, revitalizing state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and enhancing the efficiency of the banking and finance sectors. The government also introduced reforms to replace the multiple exchange rates system with a unified exchange rate. In addition, it took significant measures to improve the banking sector, and it established the Bank of the Lao PDR (BOL) in 1990 (Oraboune 2012). Economic growth during 1986-2000 remained around 5.6% per annum.

From the early 2000s onward, during the period of high economic growth in 2000-2016, five-year national socioeconomic development plans (NSEDP), have played a central role in transforming the national strategic goals and the priority development programs into action plans. In 2002, the Industrialization and Modernization Strategy (2001–2020)—which was part of the government’s 2020 development vision—was introduced to help develop the industry sector. In addition, the government focused its efforts on hydropower, mining, agricultural production, tourism, and construction material (Jajri 2015). These reforms created favorable conditions for industrialization, which was supported initially by growth in manufacturing, particularly textiles and garments. From 2000 onward, resource-based sectors made up the bulk of industrial value added. GDP growth increased further and the economy grew at 7.2% per annum during 2000–2016 (Figure 1.1).1

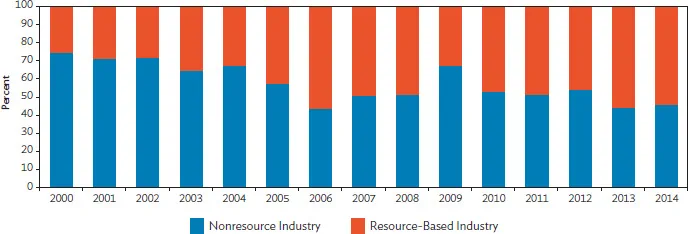

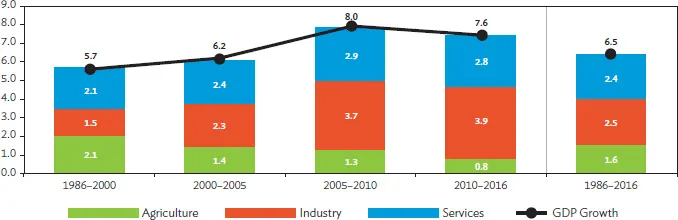

From the supply side, industry and services became the major drivers of growth. On the other hand, the contribution of agriculture declined over time. The contribution of industry to GDP growth surged from 25.6% during 1986–2000 to 37.6% in 2000–2005. It rose further to 46.9% in 2005–2010 and reached 52.0% during 2010–2016. Overall, during the period of high economic growth in 2000–2016 industry contributed 46.0% to GDP growth. As mentioned, resource-based products dominated the industry sector, and the share of resource-based industry (mining and electricity) in industrial value added surged from 25.4% in 2000 to 54.1% by 2015 (Figure 1.2).

The reliance on resource-based products, such as hydropower and mining, contributed significantly toward economic growth. However, because these sectors were capital intensive in nature, they were not a significant source of employment. Consequently, industry’s employment share declined from 8.7% in 2001 to 8.1% by 2010.

In 1986–2000, the services sector’s contribution toward economic growth was 37.1%, which rose to 39.1% in 2000–2005 and remained around 36.2% in 2005–2010. During the high-growth period of 2000–2016, the overall contribution of services remained on average at 37.1%. Within the subsectors of services, the growth rate of wholesale and retail trading, public services, and transport and communication remained strong.

The contribution of agriculture to GDP growth declined substantially—from 37.0% during the preparatory stage in 1986–2000 to 17.0% during the high-growth period in 2000–2016. An examination of the different subperiods indicates that agriculture contributed about 23.3% toward GDP growth in 2000–2005, 16.8% in 2005–2010, and 10.4% in 2010–2016 (Figure 1.3).

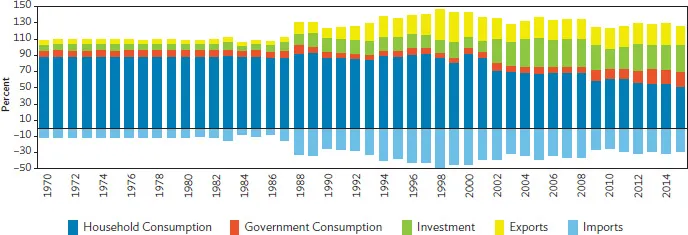

From the demand side, household consumption continued to dominate contribution to GDp growth. The share of household consumption in GDP remained around 90% during 1970–2000. However, from 2001 onward it started declining and in 2001–2015 averaged around 66%. During the same period, the share of investment in GDP increased from 11.4% to 31%. The share of exports, which was 11.8% in 1970–2000, increased further to 23.8% during 2001–2015. Against the backdrop of higher economic growth and to meet the growing consumption and investment demand, imports also surged from 21% to 32% (Figure 1.4).

1.2 Major Economic Developments: 1975–2016

1.2.1 Background and Centrally planned economy (1975–1985)

The Kingdom of Laos was a constitutional monarchy that ruled from 1953 until 1975. However, against the backdrop of political changes in Viet Nam and Cambodia in April 1975, the monarchical government was abolished. Subsequently, in December 1975, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic was proclaimed, which then adopted a centrally planned economic system.

Historically, the Lao PDR has a lot in common with Viet Nam and Cambodia. As former French colonies, they shared a common currency under the colonial rule. They also adopted a Soviet-style central planning system in the 1970s. However, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent loss of Soviet aid in the early 1990s, they began the process of economic and political reforms, paving the way for their transition from a centrally planned to a market-oriented economic system. The pace of reforms in all the three economies was quite different with regard to the degree of openness, international integration, and economic performance. Initially, these economies spent considerable time conducting reforms within the framework of a centrally planned economic system before transitioning into a market economy. For example, in Viet Nam, the “Doi Moi” movement in 1986 signaled the end of the centrally planned economic system. This coincided with the introduction also in 1986 of the NEM in the Lao PDR, which ushered its transition toward a market economy (Shimomura et al. 1994).

As a landlocked economy and the least open of the three economies, the Lao PDR gradually started introducing reforms. During its economic transformation, the government pursued an annual plan covering 1976–1977, a three-year plan for 1978–1980, and a series of five-year plans for 1981–2015. In 1975–1985, the Lao PDR pursued a centrally planned economic system. Under this regime, prices and exchange rates were determined by the government and all the industry and foreign trade sectors were nationalized. However, in the initial years of the centrally planned economic system, the country faced remarkable difficulties, and economic management during this era remained weak. At the end of 1976, socialism was introduced and relations with the West and with Thailand were abandoned, resulting in massive urban unemployment and hyperinflation to the tune of 400%.

A large amount of the assistance from Western countries was interrupted, and the foreign exchange operating fund of the International Monetary Fund, which supported budget deficit and helped settle balance of payments, was also halted. During that time, both the budget and balance of payment deficits were financed with assistance from the former Soviet Union. The subsequent droughts in 1976–1977 and the floods in 1978 made matters even worse. Moreover, sudden termination of aid from the United States (US), disruption of cross-border trade from Thailand’s economic blockade, and the peasants’ resistance to the introduction of taxation and collectivization of agriculture aggravated economic difficulties further. Increased regulations from the government also reduced the number of traders and entrepreneurs (Shimomura et al. 1994). These series of events had an adverse impact on the economy, causing it to remain stagnant with GDP growth in 1976–1979 reaching almost zero. There was a little increase in per capita income from $72 in 1976 to $83 in 1979 and standard of living remained low.

To avert the situation, the Central Committee of the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party in 1979 announced economic reforms. Both individuals and private enterprises were allowed to engage in commercial activities. The government also took steps to reduce the number of constraints on domestic and international trade. Subsequently, with the launch of the first Five-Year Plan in 1981–1985, these reforms gained momentum. The plan emphasized the self-supply of food, establishment of transportation and telecommunication networks, promotion of industrialization, and improvement of human resources development. Since the Lao PDR had a low starting base, economic growth during 1981–1985 remained strong and the economy grew at 7.9% per annum. Per capita income increased from $122 in 1981 to $163 in 1985. Despite higher economic growth, however, the major objectives of the plan, such as attaining self-sufficiency and a balanced and diversified agriculture structure, could not be achieved. Consequently, the economy continued to face high budget and trade deficits and little progress in human resources development (Shimomura et al. 1994).

1.2.2 Transition to the Market Economy (1986)

By the beginning of the 1980s, the centrally planned economic system virtually collapsed, bringing about the Lao PDR’s transition toward a more open and market-oriented economy. In 1986, the government introduced various economic reforms and introduced market-oriented economic policies under the NEM, with the aim of setting up the legal and institutional framework and restoring pr...