CHAPTER ONE

RUSSIAN STATE, POLISH SOCIETY

The origins of the Revolution of 1905 in Russian Poland can be traced back to developments in the final phase of an earlier but far different upheaval, the January Insurrection of 1863–1864. As tsarist Russia suppressed this last of a series of challenges by the Polish nobility, or szlachta, to its hegemony in central Poland, it set in motion forces that were to reshape Polish society and redefine Polish politics for decades to come. The January Insurrection was therefore an authentic historical watershed, the culminating point of the turbulent romantic era of Polish history and the point of departure for a new period, the contours of which would not be clearly visible until some forty years later.

The insurrection that erupted in January 1863 resulted from frustration and disappointment with the limited concessions offered the Kingdom of Poland by Alexander II shortly after he succeeded to the Russian and Polish thrones in 1855. Since the suppression of the November Insurrection of 1830–1831, the Kingdom had suffered the “iron rule” of Nicholas I and his viceroy in Warsaw, Gen. Ivan F. Paskevich. The Kingdom’s autonomous status within the Russian Empire, supposedly guaranteed by agreements reached at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, had been reduced to a legal fiction. In effect, the country was ruled by military decree for almost a quarter of a century. Then came the disastrous defeats of the Crimean War, also inherited by Alexander from his father, which convinced the new tsar that limited reforms were necessary in Poland to avoid a prospective uprising. Consequently, Alexander issued an amnesty for Poles exiled to Siberia in 1831, reopened institutions of higher learning, and restored the right of assembly to permit participation of the Polish elite in the statewide debate on planned reforms, especially peasant emancipation.

Unfortunately, Alexander’s relaxations, designed to secure greater stability and loyalty to the throne in the Kingdom, had the opposite effect. Legally recognized organizations with moderate yet undisguisedly political aims, such as the Agricultural Society and the Warsaw City Delegation, emerged, emboldening radicals to form conspiratorial circles and organize patriotic street demonstrations. To contain the growing political unrest and restore discipline, the tsar in 1861 turned to the aristocrat Aleksander Wielopolski, an arrogant and determined “realist’, who believed he could manage the crisis by continuing to hold out the carrot of reform while selectively applying the stick of repression. As head of the country’s civil administration, Wielopolski imposed martial law, forced the disbanding of the Agricultural Society and the City Delegation, and undertook a series of preventive arrests. Finally, on January 14, 1863, Wielopolski announced the draft of thirty thousand young men into the military service in an effort to force the opposition out into the open.

Instead, that opposition retreated to the underground, where it formed an insurrectionary government and launched a guerrilla war that harassed the Russian army for sixteen months. As the insurrection quickly spilled over to Lithuania and Byelorussia, the eastern borderlands of the prepartition Polish Commonwealth, both sides sought to win the support of the peasantry by offering more favorable terms of emancipation. In this single most important social issue of the insurrection, the tsar had the last word. Aided by a massive bureaucracy that could implement his escalating promises to the peasants, Alexander outbid an insurrectionary government forced to operate in the shadows and whose authority was limited to territory that it never held for more than a few days at a time. With the emancipation decrees of March 2, 1864, the autocracy effectively took the wind out of the sails of the insurrection and left it without a popular base of support. The denouement came five weeks later, with the capture of Romuald Traugutt, the last “dictator” of the insurrectionary government. Organized Polish resistance came to an end.1

Russian Reaction to the January Insurrection

Abrupt changes in Russian policy toward the Kingdom followed the suppression of the insurrection. The modest relaxations and limited reforms of the pre-January period now gave way to harsh retaliation for Polish “ingratitude.” Especially targeted for retribution were the gentry and the Catholic clergy, perceived by the Russian authorities as the leading social forces behind the rebellion. More than six hundred persons of predominantly gentry origin were sent to the gallows. Tens of thousands were exiled to Siberia, where a significant proportion served out hard-labor terms. Some ten thousand others escaped similar punishment by fleeing the country.2 Economic deprivation went hand in hand with political revenge. The government confiscated 1,660 estates in the Kingdom and 1,794 estates in Lithuania from the Polish gentry. Another eight hundred estates, belonging to property owners considered politically unreliable, were forcibly sold at auction. Moreover, to maintain post-insurrectionary Russian armies of occupation, contributions totaling thirty-four million rubles were levied on those gentry who remained on the land. One historian estimates that 250,000 lives were affected by the various measures of repression.3 Together they dealt a devastating blow to the traditional Polish elite.

The Roman Catholic Church was simply terrorized into submission. Some members of the hierarchy were kidnapped and held hostage in the depths of Russia; others were forcibly removed from their ecclesiastical offices. By 1870, not one Polish bishop in the entire Kingdom remained in his diocese, and, for several years thereafter, the episcopate ceased to function. In the meantime, hundreds of lower clergy joined their gentry countrymen in tsarist prisons, Siberian exile, and forced emigration. The autocracy also found a pretext to end its limited toleration of the Uniate (or Greek Catholic) Church in the Kingdom’s eastern provinces. For centuries, the Uniate faithful had been considered by the autocracy as religious renegades from the officially recognized Orthodox Church and were largely persecuted out of existence in the Ukraine and Byelorussia. In 1839, Nicholas I severed all contact between the Uniate Church and the Vatican as a first step toward introducing that persecution into the “autonomous” Kingdom. Now, in 1875, the Uniates who remained in the Chełm and Podlasie regions of the Kingdom were disenfranchised, and hundreds of thousands were “reconverted” to Orthodoxy by coercive means. Any hopes for political or moral assistance from Rome were dashed in 1882 when a modus vivendi was reached between the Russian government and the Vatican. Abandoned by Leo XIII to the mercies of the Russian caesar and fearing further deprivations, the Polish church went into a decades-long hibernation.4

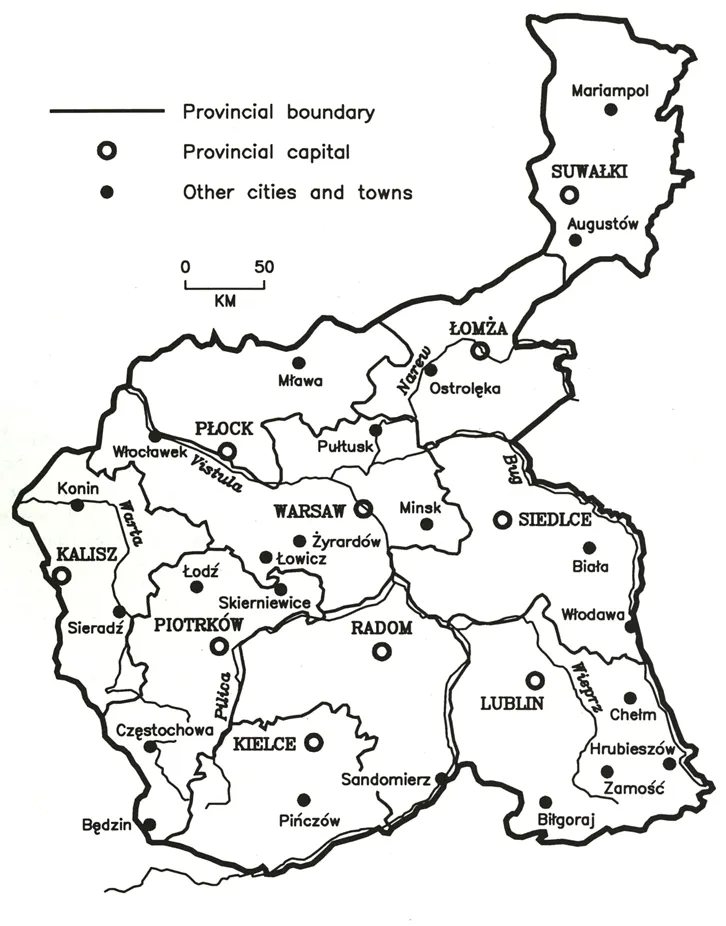

Meanwhile, the legal fiction of the Kingdom’s autonomous status was dropped. As an immediate consequence of the failed insurrection, thousands of Poles were purged from the civil administration and replaced by Russians. All separate administrative institutions that had survived the reign of Nicholas I were then quickly eliminated. With the death of Count Berg in 1874, the office of viceroy was discontinued and replaced with that of the Warsaw governor-general, which was invested with broad civil and military authority over the administration of the Kingdom’s ten gubernii, or provinces.5 Shortly thereafter, “Vistulaland” supplanted the “Kingdom of Poland” in Russian bureaucratic parlance as the country’s official designation.

Until 1914, Russian Poland was ruled under a system of exceptional, emergency legislation, beginning with the declaration of martial law by Wielopolski in 1861. Emergency rule allowed the autocracy to deny the Kingdom the advantages of recent Russian legal reforms, such as elected justices of the peace and trial by jury for criminal cases, as well as such reforms of local government as the establishment of elected city councils and zemstvo assemblies in the countryside. At the same time, the Warsaw governor-general was empowered to issue binding decrees affecting state security and to levy a variety of administrative penalties if those decrees were violated. The Warsaw governor-general could also arbitrarily transfer the trial of civilians to military courts and order deportations to Siberia without the verdict of any court. Separate Polish scientific, cultural, economic, and philanthropic organizations could not be formed without his express permission, which in turn had to be confirmed by St. Petersburg. Moreover, the political press was absolutely prohibited (with the exception of government-sponsored newspapers), and nonpolitical publications were forced to submit to strict preventive censorship.6

In the gubernii, governors served as the highest administrative authority and together with their executive organs supervised the work of provincial-level departments. The provinces, in turn, were divided into Russian-style uezdy, or counties, headed by nachal’niki (chiefs) appointed by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, but subordinate to the governors. Despite provisions in the emancipation decrees for self-governing institutions in Polish villages and communes, the county nachal’niki regularly intervened and exercised a decisive influence in their affairs. Magistrates, headed by appointed mayors, governed the cities under the supervision of the provincial governors.

Map of the Kingdom of Poland in 1897

A massive and overlapping police bureaucracy ran parallel with the civil-military apparatus. Beginning in 1866, offices of the gendarmes were organized at the provincial and county levels, subordinate to the central office of the Warsaw Regional Gendarmes, which, in turn, was headed by the special deputy to the Warsaw governor-general for police affairs. The unique institution of the Land Guard was also introduced into the Kingdom at this time, charged primarily with preserving law and order in the Polish countryside. The Land Guards were headed by captains who, from their headquarters in the county seats, supervised units in various precincts. In provincial capitals, the chief of police also doubled as head of the county Land Guard. Police forces in major urban areas such as Warsaw and Łódź were entrusted to superintendents of police, whose powers rivaled those of the provincial governors. Beyond the regular police, some two hundred agents of the reorganized secret police, the notorious Okhrana, functioned as the “eyes and ears” of the autocracy in the Kingdom, alert to any sign of independent activity, whether political or nonpolitical.7 If this were not enough to keep the Kingdom subdued, 240,000 soldiers occupied the country.

The retributive measures of Alexander II’s reign, though they eliminated separate Polish institutions and completely incorporated the Kingdom into the empire, did not yet imply the systematic russification of the population. That became official state policy only during the reign of his successor, Alexander III (1881–1894). With the appointment of Iosif Gurko as Warsaw governor-general in 1883, the Kingdom was subjected to a dozen years of intense “denationalization” by which the Russian bureaucracy strove to divest the Poles of their national character. Through a series of arbitrary decrees, the Polish language was eliminated from all levels of administration and the courts; even the “self-governing” institutions in the villages and communes were not spared. At the same time, Poles were completely purged from the upper and middle administrative ranks. Henceforth, they would be permitted to serve only in the lower levels of the postal and railroad bureaucracies. Moreover, all legally registered associations, including the Roman Catholic Church, were now required to conduct internal correspondence in the Russian language, making it easier for the police to keep tabs on them. Of course, all business with the state authorities had to be transacted in Russian. Polish street and building signs came down and were replaced by Russian-language equivalents. The names of towns were also changed; for example, Puławy in Lublin Province became Novo-Aleksandria. In short, when the nightmare of Gurko’s tenure as Warsaw governor-general came to an end in 1894, the only places where Polish remained a public language were a few state-owned theaters in Warsaw.8

The russifiers to ok principal aim, however, at the Kingdom’s separate educational institutions. Already in 1867 a tsarist edict liquidated all traces of autonomy in the educational system as Russians took over the administration of the schools. Two years later, the Warsaw Main School, a Polish institution of higher learning earlier conceded by Alexander II, was transformed into an imperial Russian university and its faculty purged. Fluency in Russian became necessary for admission, a criterion that openly discriminated against Polish applicants. Also beginning in 1869, public secondary schools were required to use Russian as the language of instruction for all subjects with the exception of religion. Polish could be studied as an elective “foreign language” in gymnasia that had received permission from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, but only up to the sixth form. Even then, Russian was employed as the language of instruction. To implement these policies, teachers were recruited from Russia with the aid of substantial bonuses and other incentives. According to official expectations, once a sufficient number of Russians were hired, the employment of Polish teachers in the state-run secondary schools would be terminated.9

The task of consolidating and extending the russified school system fell to Aleksandr Apukhtin, curator of the Warsaw School District during the Gurko era. Before Apukhtin’s appointment, public elementary schools were considerably less affected by the “denationalization” measures. Compulsory study of Russian had been introduced, as had textbooks that eliminated references to “Poland.” Otherwise, the authorities concentrated on the teachers seminaries where Russian replaced Polish as the language of instruction. Under Apukhtin, however, Russian became the instructional language for all subjects in the elementary schools with the exception of Polish grammar and religious studies. New teachers were hired, moreover, according...