She got up, and, taking off her hat, took up from a little table an album in which there were photographs of her son at different ages…. Pulling out the photograph that was next to her son’s (it was a photograph of Vronsky taken at Rome in a round hat and with long hair), she used it to push out her son’s photograph. “Oh, here he is!” she said, glancing at the portrait of Vronsky, and she suddenly recalled that he was the cause of her present misery. She had not once thought of him all the morning. But now, coming all at once upon that manly, noble face, so familiar and so dear to her, she felt a sudden rush of love for him.

LEV TOLSTOY, Anna Karenina, part 5, chapter 31

This chapter tells the story of photography as technology as viewed through and by leading cultural figures. As a literary celebrity in the latter part of the nineteenth century, Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy became a perennial subject for the cameras of both professionals and amateurs, whose images were reproduced in the popular photographic press in its many forms: cartes de visite, postcards, and journal illustrations. Tolstoy was not the only nineteenth-century Russian author to shape and be shaped by photography, but his own spiritual crisis as an author in the 1870s coincided with the dispute about photography’s place in the schema of artistic representation, arising from doubts over whether its ability to mechanically copy nature allowed for artistry. Tolstoy’s literary work and his image as a cultural celebrity in turn-of-the-century Russia encapsulate the central issues in this modern “crisis of authorship” within a market system. At almost the same time as Tolstoy’s death, photography received its own legal resolution to its crisis of authorship in the form of modern copyright protection, crystallizing a new configuration of popular, accessible art within modern image culture. Indeed, for many people Tolstoy’s death marks the pivotal moment of the true fin de siècle: “[The figure of Lev Tolstoy] symbolized the change in epochs…. The old age ended, and a new one began, not in 1900—but in 1910, after the death of Tolstoy” and with it, a new photographic age.2 In this chapter, we will follow the trajectory of this first age of photography into its twentieth-century instantiations.

A Little History of Photography in Russia

Walter Benjamin opens his “Little History of Photography” (1931) by describing the “fog” that surrounded the earliest days of photography, which flowered before its industrialization, before the advent of mass-produced cameras and film. For Benjamin, the fog was created by a “ludicrous” stereotype—the “fetishistic and fundamentally anti-technological concept of art”—which dominated the history of photography for “almost a hundred years.” But most essentially for Benjamin, these theoreticians “undertook nothing less than to legitimize the photographer before the very tribunal he was in the process of overturning,” quite opposed to the import of photography’s technological and mechanical history.3 Here Benjamin turns our attention back to a key early text on the introduction of photography, Dominique Arago’s report to the French Chamber of Deputies in 1839. In the physicist-politician’s address, he enthuses over the many possible applications of photography, from astronomical surveys to the philological study of Egyptian hieroglyphs.4 One report from the French press, likely inspired by Arago and other proponents of the technology, was quoted in the Russian press in 1839, mimicking the fanatical excitement aroused by the advent of the daguerreotype:

The daguerreotype will disseminate the beautiful views of nature and works of art, as book printing disseminates the works of the mind of man. It is engraving, handy to each and all; a pencil, quick and obedient as thought; a mirror, which retains all impressions; a faithful memory of all monuments…; continuous, instantaneous, tireless reproduction of all the hundreds of thousands of excellent works that time creates and destroys on this earth.5

Although exaggerated, this effusion captures the great hope that photography, as Arago proposes, would become ubiquitous and the medium of an accessible mass-produced art. It would provide a helpmate for the study of human creations and the natural world, from the documentation of the cultural monuments of human civilization to the tiniest microbes beneath a microscope.6

However, the introduction of photography, as a revolutionary technology capable of entering into almost all spheres of visible creation, was also in various degrees caught up in proprietary battles. The purpose of Arago’s address was to ensure a fair and equitable recompense for Louis Daguerre and Isidore Niecpe,7 who could not secure patents for their process in the French courts.8 And, as in the West, the Russian papers featured polemics comparing Henry Fox Talbot’s calotypes9 with the daguerreotype, since Talbot was promoting the claims of his own process over that of Daguerre and Niecpe. Such claims for the superiority of proprietary technology, as well as authorial claims to the resulting prints themselves, would be a strong thematic current running through the early history of photography—and might certainly be extended to debates about patents and trademarks up to the present day. But as we will see, these proprietary questions were part and parcel of Benjamin’s much denigrated “traditional” artistry—specifically the cult value of painting—haunting and in large part dominating the first several decades of photography in Russia.10

It is not surprising that photography would try to define itself within the already existing discourse on visual production, and particularly painting, since the new technology found itself framed to a great extent by the already existing languages of the “mechanical” or “copying” arts.11 Many photographers in Russia had come to photography through painting, including William Carrick and Andrei Karelin.12 Embracing the vogue for the “psychological portrait,” early photographic innovators— opening studios from Paris to St. Petersburg—sought to capture not only the indexical likeness of the sitter but also the inner character of their subjects.13 With this aim in mind, they hoped to overcome the severe limitations of early photographic technologies—the need for controlled settings and long exposure times under diffi-cult lighting constraints.

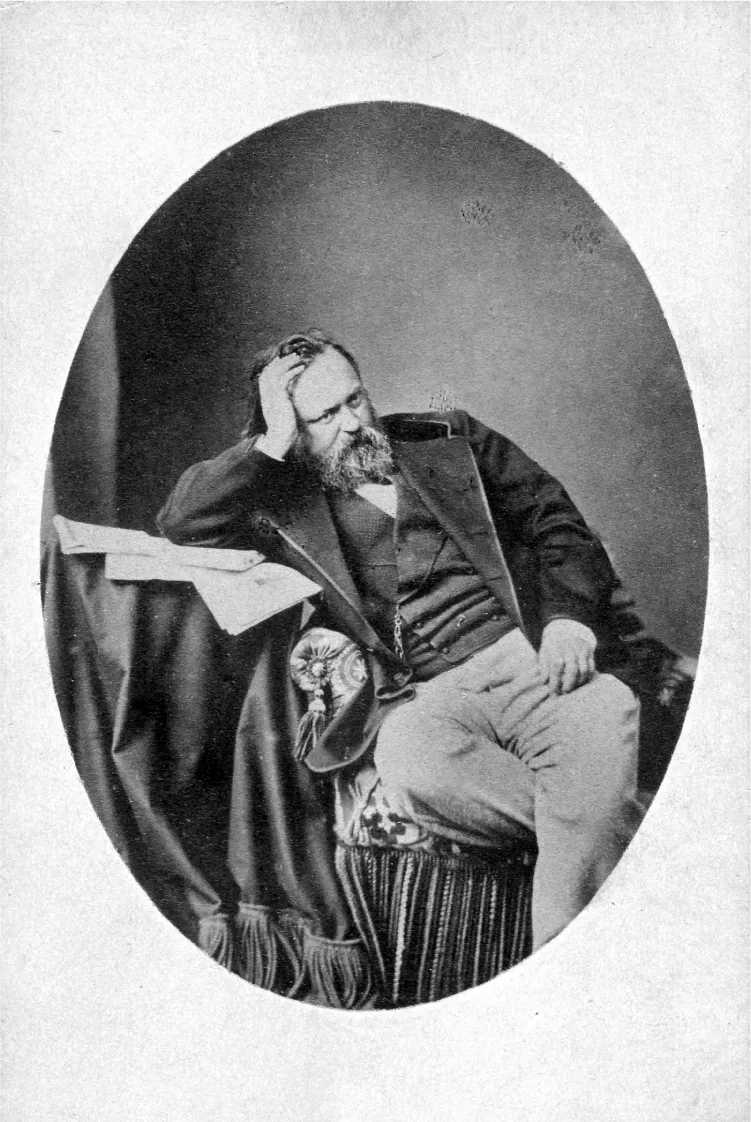

Sergei Levitsky was one such notable pioneer of the photographic arts in Russia.14 Levitsky studied under Daguerre for a time and, like a great number of other early photographers, trained as a chemist; he ran studios in both St. Petersburg and Paris.15 Levitsky is perhaps most well known for his studio photographs, taken in Russia and Paris, of famous subjects, including Tsar Nicholas II, as well as authors such as Ivan Turgenev and Ivan Goncharov. Many of his earliest portraits display the deadening formality and stiffness that necessarily characterized early photographic portraiture. But some photographs proved to be exceptions—most notably his intriguing and oft-reproduced portraits of Alexander Herzen.16 In one 1861 portrait, Herzen reclines with head on hand, seemingly peering beyond the photographer, out above the level of the camera, visually signaling to a “reality” behind the curtain (fig. 1.1). Two remarkable stories attest to the enduring impact of this photograph. The first is the fact that the image is widely regarded as the inspiration for Nikolai Ge’s painting The Last Supper (Tainaia vecheria, 1863). Ge was deeply interested in Herzen, and it was reading Herzen’s memoirs in 1861 that led him to write to the author to request a copy of the Levitsky photograph, then in circulation as a lithograph.17 Such a desire was due not only to the reputation of the radical Herzen himself but also to the striking aesthetic success of the portrait. The figure of Christ in Ge’s painting ruminates in an adaptation of Herzen’s pose. While seeming to fulfill a vision of photography in the age of painterly realism as the “handmaiden of art” (as it was designated—and degraded as “manual slavery”—by the likes of Lady Eastlake and Charles Baudelaire), in Ge’s case a photograph served as something more, as a “higher” inspiration.18

Herzen would himself remember one of Levitsky’s photographs (probably the famous reclining photograph) at the end of a dinner party during his exile in London in 1862. In his memoirs, he recalls,

The guests began to leave about twelve o’clock…. By way of thanking those who had taken part in the dinner, I asked them to choose any one of our publications [from The Bell] or a big photograph of me by Levitsky as a souvenir. [Pavel] Vetoshnikov took the photograph; I advised him to cut off the margin and roll it up into a tube; he would not, and said he should put it at the bottom of his trunk, and so wrapped it in a sheet of The Times and went off. That could not escape notice.19

And this photograph—wrapped in the (London) Times—did not escape notice. Not only were its size and its very material as a photograph hard to miss, as Herzen suggested, but it was also an image of a notorious radical figure. It was seized along with Vetoshnikov’s other documents—letters to the radical author Nikolai Chernyshevsky among them—on his way back to Russia on the following day. Vetoshnikov and his compatriots were accused of subversive (socialist) activities and exiled to Siberia.20

Figure 1.1. Sergei Levitsky, portrait of Alexander Herzen (1861); The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum. Photo by Yuri Molodkovets.

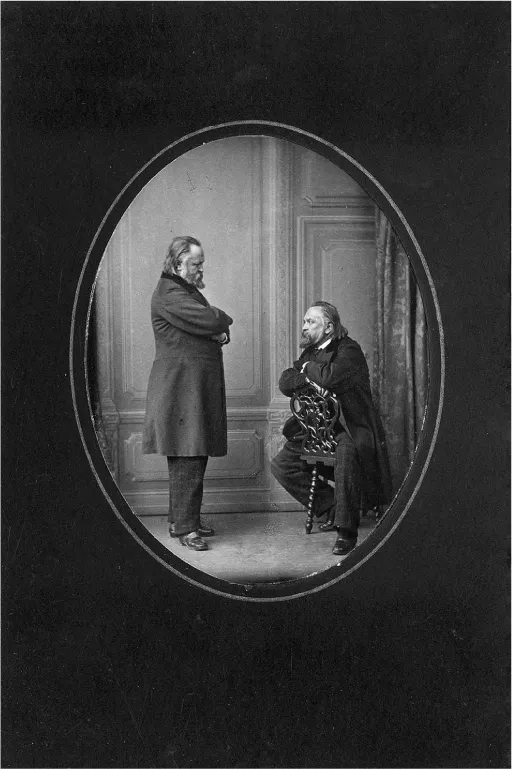

Figure 1.2. Sergei Levitsky, portrait of “Herzen versus Herzen” (1865). Image courtesy of the Russian National Library, St. Petersburg.

Also of special note is Levitsky’s sutured photograph of Herzen (fig. 1.2). In this early photo collage, a seated Herzen gazes back at a standing Herzen, a composition that played on the photographer’s (perhaps heavy-handed) attempt to suggest the inner life of his subject. This photo, and others like it, naturally made an impression on early critics: “S. Levitsky… thought to depict a personage [osoba] on one and the same card in two poses and often in two different suits. These strange drawings [risunki], in which the photographed are speaking as though with one another…, are pleasing, and I would not be surprised if they become the fashion.”21 This kind of photograph, however, did not become Levitsky’s fashion. When he returned from Paris to St. Petersburg, Levitsky took what Sergei Morozov describes as a turn toward “the path of realistic art photography” (put′ realisticheskoi khudozhestvennoi fotografii), that is, away from his “infatuation with surface effects” (uvlechenie vneshnimi effektami).22

Following the work of Levitsky, the Niz...