![]()

CHAPTER 1

Reclaiming Economics for Happiness

Happiness is the meaning and the purpose of life, the whole aim and end of human existence.

— Aristotle

One must make a new system that makes the old system obsolete.

— Buckminster Fuller

Reclaiming the Language of Economics

Economics and the gospel of economic growth have failed humanity when it comes to delivering the well-being we all desire: to live happy and meaningful lives. The economics of eternal growth has lost touch with the original Greek meaning of the word economy (oikonomia), which referred to the wise management of the household. Instead, genuine economics—a concern for the well-being of the household—has been usurped by a culture of hedonistic materialism and love of money. Aristotle argued that chrematistics—the art of getting rich, or the science of making and accumulating money—was an unnatural activity that dehumanized those who practiced it. He condemned the practice of making money from money, stating unequivocally, “The trade of the petty usurer is hated with most reason: it makes a profit from currency itself, instead of making it from the process which currency was meant to serve. Their common characteristic is obviously their sordid avarice.”

While the word usury seems to have faded from the consciousness of modern times, Pope Francis seems to agree with Aristotle and the 14th-century theologian Thomas Aquinas1 in condemning it:

I hope that these institutions may intensify their commitment alongside the victims of usury, a dramatic social ill. When a family has nothing to eat, because it has to make payments to usurers, this is not Christian, it is not human! This dramatic scourge in our society harms the inviolable dignity of the human person.2

Today modern usury happens whenever private banks make new loans, creating new money (ex nihilo: out of nothing) as simple bookkeeping entries in their ledgers unattached to real assets. The costs to all of society are the interest charges on each loan. The totality of all loans created primarily by private banks in every economy constitutes the total debt-money supply of nations.

Returning the world to the original vision of economics as the Greeks defined it will require a serious examination by economists of the evidence that usury—the creation of money as debt and the charging of interest—has indeed decimated the well-being of millions of households and made the pursuit of genuine happiness difficult, at best.

As an adjunct professor of corporate social responsibility and social entrepreneurship at the University of Alberta’s School of Business, I would ask my business students, What is an economy for? What is the real purpose and role of business in an economy? What is the role and responsibility of business in a society focused on returns to well-being? Why do we measure progress the way we do? Why is it that despite rising levels of gross domestic product (GDP), we have diminishing levels of self-rated happiness in the US, as well as the erosion of many well-being conditions? If the promise of a rising tide of continuous economic growth was to lift the prospects of every American household, why has it failed to do so in the land that espouses the pursuit of happiness as its highest aspiration? How is it that governments operate without a complete balance sheet that shows the assets and liabilities of the human, social, natural and built assets of the state or nation? What if the progress of our economies were measured in terms of the conditions of well-being and self-rated happiness that psychologists tell us contribute most to our genuine happiness and societal well-being, including the strength and joy of our relationships?

Happiness: Well-Being of Spirit

It is worth repeating that Aristotle defined the word happiness in terms of the Greek work eudaimonia, which translates literally into “good spirit.” Another translation is “human flourishing” or “the good life.”3 I would define happiness as “the well-being of one’s spirit or soul.” The Oxford Dictionary defines well-being as “the state of being comfortable, healthy, or happy.” Happiness is much more than a pleasant or contented mental state. Happiness is a mental or emotional state of well-being that can be defined and measured as a range of emotions from contentment to intense joy. Joy itself is perhaps the ultimate aspiration—a state of bliss. Aristotle said that happiness results from a good birth, accompanied by a lifetime of good friends, good children, health, wealth, a contented old age and virtuous activity. The Buddha agreed with Aristotle that the purpose of our lives is to be happy.

Ultimately, Aristotle defined eudaimonia as the rational activity of the soul in accordance with virtue in a complete life. It is the basis of Aristotle’s ethical and political theory, the goal of all action, which can be attained through virtue. For this reason, Aristotle’s ethics and politics were heavily focused on virtue.4 This was also true of Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson; Jefferson noted that without virtue one cannot be happy.

Imagine if Thomas Jefferson, who penned the US Declaration of Independence, had replaced the word happiness with well-being, as follows: “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal and independent, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent and inalienable, among which are the preservation of a good life, and liberty, and the pursuit of well-being.”5

What has become of virtue in our modern politikos? How would the US measure its progress through this new aspirational lens of well-being, including both spiritual and other aspects of well-being and a good life?

A New Index of Well-Being

Since the 1970s, some progressive economists (along with Robert Kennedy in 1968) have been advocating for a new economic measure of welfare to either replace or modify GDP and national income accounts with a new measure or index of progress. It wasn’t until 1996 that the San Francisco-based economic think tank Redefining Progress produced a new measure of sustainable economic well-being, which they called the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI). The GPI was inspired by the seminal 1989 work For the Common Good by Dr. John Cobb Jr. (one of the two most important American theologians of the 20th century, from Claremont School of Theology in California) and Dr. Herman Daly (an ecological economist and advocate for a steady-state economy from the University of Maryland).6

In 2004 positive psychologists Dr. Ed Diener (University of Illinois) and Dr. Martin Seligman (University of Pennsylvania) proposed the development of a national well-being accounting system and index for the United States. This system of well-being accounts would systemically assess key variables of well-being such as trust, belonging, engagement, meaning and life satisfaction. This would be a subjective well-being index based on the perceptions of Americans. However, to date no such national well-being accounting system or index has been adopted by the US or any US state or city, with a few exceptions, including the city of Santa Monica, California, which has adopted a Wellbeing Index to measure and actively improve the state of the community.7

Nonetheless, the US Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index, which claims to be the “Dow Jones of Health,” is produced daily. The Index tracks well-being aspects of the lives of a sample of 1,000 Americans each day. The methodology underlying it uses the World Health Organization’s definition of health as “not only the absence of infirmity and disease, but also a state of physical, mental, and social wellbeing.”8 The Well-Being Index includes citizen self-ratings of economic confidence, work satisfaction, overall happiness, hope and other variables. While Gallup-Healthways reports on state-level well-being, there is still no national well-being index we might contrast with changes in the US GDP.

The happiest state in the union is consistently Hawaii, which, according to Gallup-Healthways, reached the top spot once more in 2015, for the fifth time since they began tracking well-being in 2008. Alaska is typically ranked second, while West Virginia and Kentucky consistently rank the lowest and second-lowest in well-being nationally.

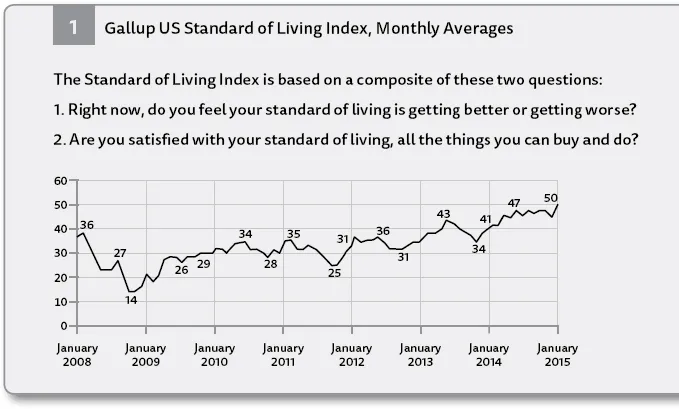

One of the more interesting trends involves Americans’ perceptions of their standard of living (is it getting better or worse?) and whether they feel their economic future is bright or dark. The graph suggests that a growing number of Americans feel satisfied with their current standard of living and are more hopeful about their economic future compared with 2008, the year of the financial crisis.

SOURCE: gallup.com/poll/180449/standard-living-index-climbs-highest-years.aspx.

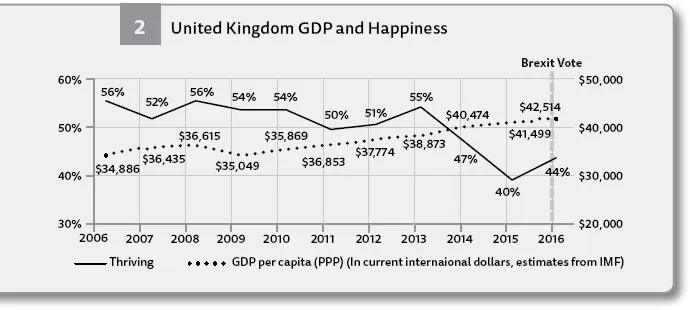

However, a different picture emerges in the United Kingdom. According to a UK Gallup poll, UK citizens’ perceptions of “thriving” or happiness show a marked decline since the Brexit referendum vote of June 23, 2016, which led to the UK planning to leave the European Union. In the two years leading up to Brexit, Gallup found that the percentage of people who were “happy” (or “thriving”) was already in dramatic decline. In fact, the 15-percentage-point decline in the percentage of people rating their lives positively enough to be considered thriving was so dramatic it remains among the largest two-year drops in Gallup’s history of global tracking.9 This was in spite of a 2% increase in the country’s gross domestic product and a relatively low unemployment rate of 4.9%.

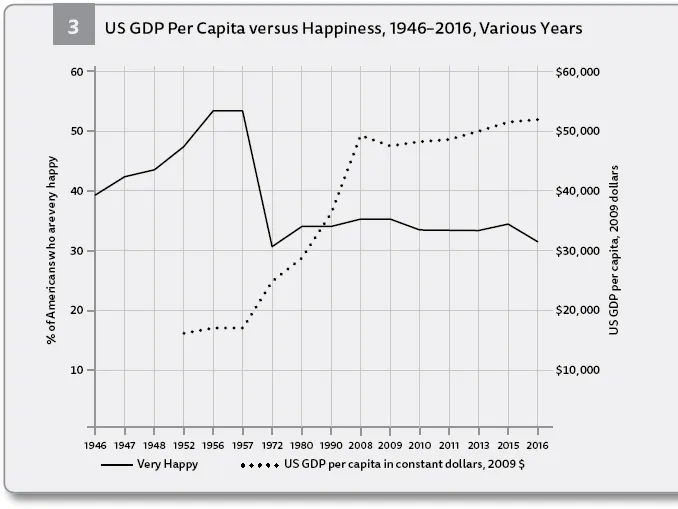

In the United States, levels of happiness have been in decline since the early 1950s, when the first happiness polls were taken. The levels of very happy and happy people reached a near recorded low in 2016, with only 31% of American’s feeling very happy compared with 53% in the early 1950s (see Figure 3).10 Yet at the same time, real (inflation-adjusted) GDP per capita has continued to rise.

SOURCE: Gallup World Poll and UK GDP statistics.

The Harris Poll® Happiness Index,11 which uses a series of questions to calculate Americans’ overall happiness, found that in 2016, fewer than one in three Americans (31%) were very happy, down from just over one in three (34%) in 2015. At the same time, however, about eight in ten US adults (81%) say they are generally happy with their life right now, suggesting that people may overstate how happy they really are.

SOURCE: Data for US happiness is from the Harris Happiness Index Poll 2008–2016. Previous happiness survey results are from various sources including Oswald J. Andrew, “Happiness and Economic Performance.” The Economic Journal, 107, November 1997, 1815–1831. US GDP per capita is from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis data.

Kathy Steinberg, managing editor of the Harris Poll, points out that as part of the survey, pollsters don’t ask “Why do you feel this way?” or “What has changed?” Bu...