![]()

1

Introduction

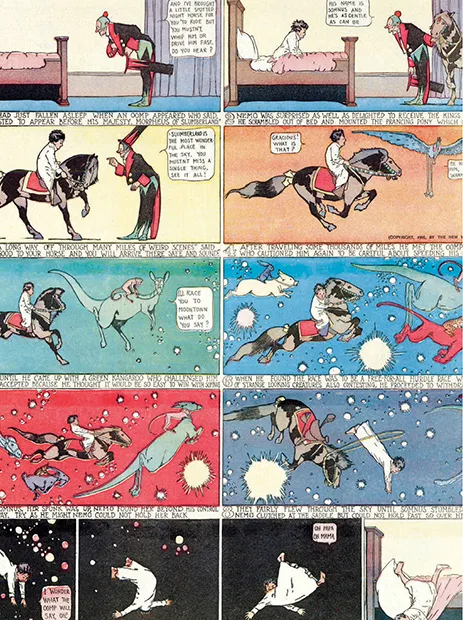

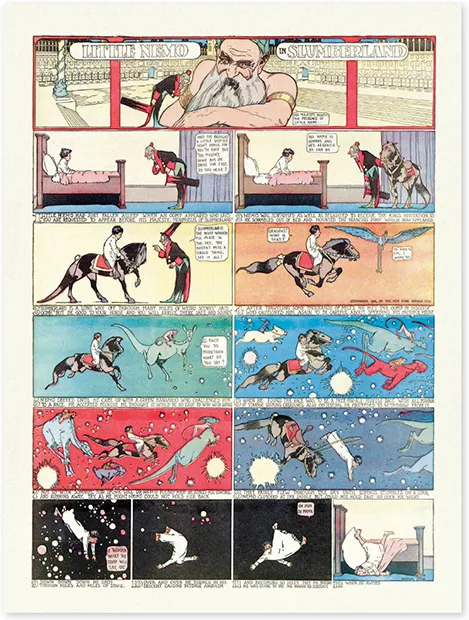

A young, tousled-haired boy about the age of six is sitting upright in his bed, ensconced in a non-descript, middle-class bedroom (fig. 1.1). His sleep has been interrupted by the appearance of a green-faced clown, deeply bowing before him in a top hat and tails, and imploring the youngster to travel with him to an enchanted, faraway kingdom. And with that solemn yet magical entreaty, so begins Winsor McCay’s epic comic strip adventure, Little Nemo in Slumberland.

In the daily and Sunday editions of American newspapers, McCay created elaborate narratives of anticipation, abundance, and unfulfilled longing. His comics redefined the medium at a decisive historical moment and made a lasting contribution to the proliferation of fantastic imagery at the dawn of the twentieth century. He successfully translated the experience of modernity into a visual language and, in the process, shaped an audience for his work. Little Nemo in Slumberland was a weekly comic strip in which the title character repeatedly embarked on epic journeys to exciting, strange, and sometimes frightening places, only to awaken in the last frame safe in his bed at home. In McCay’s other major comic, the sophisticated and cynical Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, a succession of hapless dreamers was subjected to nightmarish visions of everyday modern life only to awake, like Nemo, to reality in the final panel.

Fig. 1.1

Winsor McCay, Little Nemo in Slumberland, New York Herald, October 15, 1905, Courtesy of Peter Maresca and Sunday Press Books

While McCay’s role as a pioneer of comic art has been acknowledged, no study as of yet gives critical, art historical attention to his work. In addition to providing close readings and visual analysis of individual comic strips, this book will situate McCay’s artwork in the context of the period’s broader preoccupation with dreaming and fantasy—and consider its ties to the rise of new forms of commercialized entertainment and mass culture. I will be foregrounding the modernist sensibility present in McCay’s comics, in an effort to position mass culture and modernist art in conjunction, as opposed to acting in opposition, to one another; arriving at similar conclusions despite originating from very different places on a continuum of creative practice.1 If anything, the false dichotomy between mass culture and modernism has served to promote cultural hierarchies that have yet to be fully dismantled.

Born in Michigan in 1867 as Zenas Winsor McKay, he was the son of Robert and Janet Murray McKay (the family changed their surname at a later date, allegedly to avoid a bar fight.)2 Robert and Janet met in Ontario, where both were raised by Scottish immigrants who had come to Canada in the mid-1830s. The young couple moved to Michigan in 1866 in search of employment. Upon settling in Spring Lake, Robert McKay held several different jobs, initially working as a teamster, a retail grocer, and eventually as a real estate agent. Robert gave his first son an unusual albeit aspirational appellation, naming him after an American entrepreneur he had met in Canada named Zenas G. Winsor. The artist would drop Zenas in favor of his middle name early in his career.

Winsor had an interest in drawing since childhood, though his parents had other plans for him. His father claimed that “from the time he was a little fellow, all the while he was in school, he was drawing pictures. He used to get whipped in school for drawing sketches on the leaves of his books until I told the teachers it was of no use; nothing could stop him.”3 The insatiability of McCay’s drawing habit would come to define his unimaginably prolific career, while voraciousness provided a thematic undercurrent to many of his comics, including The Story of Hungry Henrietta and Little Sammy Sneeze, with its tagline “he just simply couldn’t stop it,” neatly echoing the commentary provided by his father.

According to Judith O’Sullivan, McCay had only six years of formal schooling.4 In 1886 McCay, then a teenager, was sent to Ypsilanti to attend Cleary’s Business College. He soon began skipping classes and sneaking off to Detroit, where he earned pocket change by drawing portraits of visitors to a local dime museum called Sackett & Wiggins’s Wonderland and Eden Musée. McCay attracted the attention of John Goodison, professor of drawing and geography at Michigan State Normal College. Though McCay never formally enrolled there as a student, Goodison taught him how to draw with an emphasis on geometrical forms and linear perspective.5 Course descriptions reveal Goodison’s pedagogical approach, which was that “real objects and not copies form the subject of the lessons and the laws of perspective are learned by observation. The lessons include drawing the geometrical solids and objects of similar forms and the elements of linear perspective … No drawing books are used. The instruction is given from the blackboard and large-scale crayon drawings. The course also includes lessons in harmony and color contrast.”6 McCay himself made mention of the program’s emphasis on geometric solids, recalling that he had been taught to draw, “a cone, a sphere, a cylinder, and a cube.”7 These lessons had a notable impact on McCay’s work, which was often praised for his attention to line, form, and perspective. However, this was the full extent of McCay’s formal art training.

With Goodison’s encouragement he moved to Chicago in 1889, intending to study at the Art Institute. Instead, McCay became an apprentice at the National Printing and Engraving Company, a firm that specialized in “Show, Commercial and Railroad Printing.” While in Chicago, McCay rented a room in the home of future illustrator and muralist Jules Guérin. At the time both men were young and struggling artists, McCay was twenty-two years old and Guérin was twenty-three. According to one account the men became friends and pooled their expertise—with McCay teaching Guérin about perspective and detail while Guérin shared his knowledge of color and figure-drawing.8

After two years in Chicago, McCay relocated to Cincinnati in 1891, where he found work at Kohl and Middleton’s Dime Museum painting signs and posters advertising the museum’s attractions. He also painted stage sets for the museum’s performing acts and human curiosities. McCay’s experiences at the Dime Museum drawing exotic animals and freak show acts would later inform his fantastic depiction of Slumberland. He spent nine years at the museum on Vine Street before leaving the entertainment district to work as a newspaper illustrator at the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune. Prior to the publishing industry’s adoption of halftone photography, staffs of newspaper illustrators were needed to document current events in the period. McCay’s work as a newspaper illustrator taught him to draw quickly and precisely, often sketching from memory, in order to convey the drama of a scene.

Two years later he joined the staff of the Cincinnati Enquirer, where he eventually became head of the art department. At this time he first began to explore the comic strip form and created a series inspired by Kipling’s Just So Stories called A Tale of the Jungle Imps by Felix Fiddle.9 In 1899 McCay began publishing single panel cartoons in the humor journal Life, which brought the artist exposure on a national scale. Life, Puck, and Judge were the top three humor periodicals in the country at the end of the nineteenth century. All three derived their format from European counterparts, most notably England’s Punch magazine.

McCay’s reading of humor periodicals led him to the work of Arthur Burdett Frost, an artist he called “the greatest comic draftsman in the history of this country.”10 A. B. Frost had studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts under Thomas Eakins; there he encountered the stop-motion photography of Eadweard Muybridge. This in turn led to Frost’s experiments with sequential action and depicting the figure in motion, which also owe a great debt to the Swiss cartoonist Rodolphe Töpffer.11 All three figures had a lasting influence on McCay. Töpffer was known in the United States as early as 1842, when his first comic story Histoire de Monsieur Vieux Bois was published as a newspaper supplement under the title The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck. Töpffer’s variations in the size and shape of his panels, as when he contracted and expanded the panels in his Histoire d’Albert, enabled McCay to see how such visual effects could either advance or slow the flow of time in his work.

In September 1903 a former colleague working as a reporter in New York brought McCay’s work to the attention of J. C. Baker, the art director for the New York Herald. Baker recruited McCay by telegram the following month to draw comic strips for the paper. Upon moving to New York McCay developed several different strips including Little Sammy Sneeze, Hungry Henrietta, A Pilgrim’s Progress, and The Dream of the Rarebit Fiend. He experimented with the comic strip medium from the very beginning by dismantling conventions and exploring new points of view, as on one occasion when a Rarebit Fiend comic strip was drawn from the perspective of a man being buried alive. Invoking a scene out of Edgar Allan Poe, the images show the point of view of a poor man watching helplessly as onlookers denigrate him and dirt is hurled upon his grave. From the early days of his career at the Herald, McCay played with time and motion. In Hungry Henrietta he rapidly aged the title character from week to week, thus speeding up the aging process, and in Sammy Sneeeze, he took the instantaneous act of sneezing and slowed down time by drawing the act out into six panels of isolated movements.

McCay’s most successful title was Little Nemo in Slumberland, a series that ran nationally as a syndicated feature from 1905 to 1914 (and was briefly revived between 1924–1927). Unlike the newspaper comic strips of today, Little Nemo, which appeared in the color supplement of the Herald, was printed on a full-size newspaper sheet, roughly 16 by 21 inches. McCay’s work was characterized by his skillful draftsmanship and intricate detail, his eye for color, and his depictions of imaginative architectural forms. His stylistic innovations included varying the size and shape of his panels, thereby expanding the narrative possibilities of the comic strip. He was attentive to the full-page design, while his graceful line work and use of flat areas of color are reminiscent of the art nouveau poster art of Alphonse Mucha and Eugène Grasset. His fantastic imagery is very much rooted in the spectacular world of commerce and popular entertainment that ushered in the twentieth century.

F. F. Proctor, a renowned vaudeville producer, recruited McCay to develop a quick sketch act in 1906. Such acts, called chalk talks, featured a performer standing at a chalkboard and drawing for the audience while delivering a monologue. McCay created an act called “The Seven Ages of Man,” in which he drew male and female faces and progressively aged them through subtle additions to the drawing. Other cartoonists, including R. F. Outcault and Bud Fisher, were similarly engaged as featured novelty acts on the vaudeville circuit at this time.

In addition to his weekly newspaper comic responsibilities and a hectic vaudeville touring schedule, McCay somehow found time to experiment with animation in his free time. Inspired by the early experimental animated films of J. Stuart Blackton and Emile Cohl, McCay began creating his first animated short, an arduous process that entailed drawing four thousand individual frames by hand. The drawings and a live-action prologue were then filmed at Vitagraph Studios, which was located only two miles from McCay’s home in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn. His first film, Little Nemo, which was also the first film to feature animated characters from a comic strip, was released on April 8, 1911. Within a few days McCay was using the film as part of his vaudeville act, demonstrating just how permeable the worlds of comics, film, and theatre were in New York at the dawn of mass culture.

The fusion of these worlds is nowhere more evident than in McCay’s twelve-minute film, Gertie the Dinosaur. The film debuted as part of the artist’s vaudeville act at the Palace Theater in Chicago in 1914. McCay prepared his audience for what they were about to see by explaining the process of how animated films were drawn, photographed, and projected. Outfitted in a top hat, tails, and carrying a bullwhip, McCay played the role of circus ringmaster, commanding Gertie, his dinosaur subject, to perform. To the audience’s amazement, the animated film appeared to respond to McCay’s commands, creating the illusion that the man and his animated film were interacting live upon the stage. As one reviewer raved, “You are flabbergasted to see the way the reel minds its master.”12 The performance showcased the artist’s dexterity and ability to navigate among the different emerging realms of mass culture.

To create a richly textured world that engaged viewers and excited their imaginations, Winsor McCay drew from a broad spectrum of visual sources. References to vaudeville, department store windows, circus posters, and amusement parks abound in his designs, thereby producing a dreamworld shaped by the visual language of modern urban experience. For the artist, Slumberland was a retreat from modernity, yet his spectacular landscapes were peppered with pop cultural allusions. McCay’s comic strips were highly self-reflexive and ambivalent: his work articulated the complex ways in which fantasy and mass culture were entangled at the turn of the twentieth century. He used the iconography of popular urban entertainment to enrich his otherworldly visions—doing so allowed him to illustrate both the lures and potential snares of this new fantasyland of mass culture.

Despite working within a tightly constructed narrative framework, McCay demonstrated the creative potential of the medium by varying the size and shape of panels and by employing innovative perspectives. For Nemo the journey never ends: he spends months attempting to reach Slumberland, and on finally arriving he is then sent on to other locations. Satisfaction is constantly deferred and travel is often comically linked with consumption. The landscapes Nemo traverses change from week to week: from palace to metropolis, to shantytown, to jungle. By situating Nemo’s adventures in such clichéd, politically charged sites, McCay conjured up a social geography that replicated contemporary attitudes about the world and its hierarchies. By pointing to the dark, dangerous side of dreaming, McCay revealed the slippery intersection of fantasy and commerce. With Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend he underscored the tension between the dreams and reality of the disaffected, displaced urban subject. His protagonists seemingly embodied an ideal consumer: passive, yielding, and never satisfied.

Chapter two introduces the major themes of the book through close examination of one particularly groundbreaking and self-reflexive episode of Little Sammy Sneeze, an early McCay serial that ran in the New York Herald from 1904 to 1906. It followed a small boy whose potent sneezes leave a trail of mayhem in his wake. In the aforementioned strip Sammy’s raucous sneezes even shatter the frame that contains him, dismantling the divide between viewer and subject. I describe McCay’s innovative explorations of time and motion within the narrative space of the comic strip, as well as his depiction of sneezing as a disruptive social practice, one that acts on the body much the way the comic strip interrupts the sober narrative o...