![]()

Chapter 1

Sometimes, Even College Administrators Act Like Freshmen

During the 1950s, every facet of life in the Magnolia State, including sports, was considered segregated. In the aftermath of the Brown vs. Board of Education decision, Mississippi became an increasingly hostile and dangerous place. According to historian Michael Vinson Williams, “White Mississippians considered the Brown decision an all-out attack upon their way of life,” and while paranoia infested the white residences of Mississippi, it was the black community that would pay the price.1 By 1955, the Citizens’ Council, which was formed in the aftermath of the Brown decision, grew to sixty thousand members statewide and had considerable influence in the areas of government, education, and newspapers.2 Blacks were put in a subservient position to whites and, for the most part, lived in squalor.3 If a member of the black community dared challenge the second class nature of their citizenship, they were typically met with deadly consequences. In 1955 alone, both the Reverend George Lee and Lamar Smith were murdered for attempting to register blacks to vote.4 The subsequent murder of fourteen-year-old Emmett Till, together with the deaths of Lee and Smith, helped create an atmosphere of intimidation and fear that solidified the extreme approach many in the Magnolia State would use to protect the Closed Society.5

Within this increasingly hostile and dangerous environment, the football Bobcats of Jones County Junior College would embark on a brief journey in the December twilight of 1955 that would challenge the state’s veil of white supremacy and usher in a new standard of segregation in sports. After finishing the season with a 9–1 record, head coach “Big” Jim Clark and his squad was rewarded with a trip to Pasadena, California, to play for the junior college national championship against the Tartars of Compton (California) Junior College. While most Mississippians were seemingly uninterested in the exploits of a junior college football team, the Bobcats became the bane of segregationists statewide when it was discovered that Compton fielded an integrated team.6 While school officials and members of the Junior Rose Bowl selection committee were aware of the Tartars’ integrated status, a number of Mississippi’s more prominent journalists and politicians took issue with the team’s participation, arguing that a Junior Rose Bowl appearance for the Bobcats could be interpreted as a step towards integration and a threat to white supremacy within the state.7

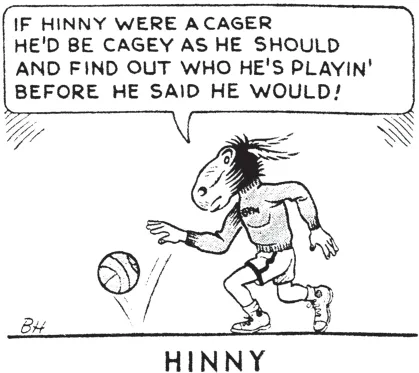

Bob Howie of the Jackson Daily News penned a “Hinny” cartoon aimed at Mississippi State and Ole Miss’s participation and withdrawals from the integrated Evansville Invitational Basketball Tournament and the All-American Holiday Tournament in December 1956. Courtesy Bob Howie/Jackson Daily News.

For a two-week period in December 1955, what initially began as Jones County’s innocent quest for gridiron dominance became one of the more highly contested issues in state newspapers. With the Brown decision still fresh in the minds of Mississippi’s political and journalistic elite, most editors and reporters either protected the Closed Society and damned the JCJC contingent for its violation of Mississippi’s traditions and way of life for a chance at championship glory, or turned a blind eye to the issue, expressing no opinion on the matter and thus seemingly supporting the segregated elite and the opposition to JCJC’s championship efforts. Because of the perceived threat of integration, Mississippi’s journalists either acted to create a negative view of the contest or depended on wire content and remained silent, negating the overall social importance of the issue to the news-reading audience. More often than not, the issue was overlooked or buried within the confines of newspapers in accordance with the protection of the Closed Society. By ignoring the issue, journalists ensured the audience’s interest in the topic would be fleeting. It was this sort of journalistic neglect that would plague debates surrounding the validity of integration in Mississippi athletics for years to come.8

Perhaps no newspaper or journalist voiced more vehement objections than Jackson Daily News editor Frederick Sullens. One of the more racist representatives of Mississippi’s journalistic past, Sullens often looked at issues of race as a personal vendetta and was an ardent supporter of the Citizens’ Council.9 The work of Sullens and the Hederman-owned Jackson Daily News epitomized the ideals and characteristics of Silver’s Closed Society, and the debate involving Jones County was no different. While many of his journalistic peers on news desks and in sports sections remained silent, Sullens wrote with the tone of a religious zealot, calling JCJC’s presence in the Junior Rose Bowl “a flagrant violation of the Southern way of life, a spineless surrender of the principles all true white Mississippians hold near and dear, and all those responsible deserve the sharpest rebuke it is possible to administer.”10 The editor openly cheered for JCJC to receive a “stinging defeat” and attributed the decision to “greed for gate receipts and a little fleeting fame.”11 Despite Sullens’s imprecations, JCJC would play in the game, losing to Compton 22–13.12

While many historians have noted Sullens’s venomous tone, his influence in the Closed Society was unparalleled. After he penned these comments and recommending that the State College Board cut funding from Jones County Junior College for their participation in the game, his work was picked up by the Associated Press and published in newspapers across the state, extending his racist reach even further.13 The work of Sullens during the JCJC-Compton controversy demonstrated the power the press had in Mississippi and the extent to which the Closed Society had infiltrated its ranks. Because of Sullens’s connections within the Closed Society, his commentary likely had a profound influence on the creation of the unwritten law months later.

The shadow cast by the loss of Jones County in the Junior Rose Bowl was considerable. On January 19, 1956, Mississippi newspapers reported that State Representative R. C. McCarver of Itawamba County had proposed a bill that would legally prohibit the state’s collegiate teams from participating in integrated competition.14 The political climate in Mississippi favored McCarver’s proposal, as segregationist governor J. P. Coleman led the Magnolia State. Coleman was a graduate of the University of Mississippi who ran for governor in 1955 on the platform of quietly maintaining segregation in the state’s colleges and universities. Coleman would later oppose the admission of James Meredith to his alma mater.15

Press coverage of McCarver’s proposal was minimal. Both the Jackson Daily News and the Clarion-Ledger, considered two of the more racist journalistic representatives of Mississippi during the civil rights era, featured front-page accounts of the proposed law on January 19, 1956. The articles, which lacked a byline, cited Jones County participation in the Junior Rose Bowl as justification for McCarver’s proposal. However, the Clarion-Ledger’s account differed from its sister publication by mentioning that JCJC played in the game despite the objections of state politicians and journalists, and lost. The same article, minus the political reference, also appeared in the Meridian Star, an indication that the commentary was omitted by the editors of the Star or, the more likely scenario, added by an editor in the Clarion-Ledger.

Despite the fervor surrounding the JCJC Junior Rose Bowl appearance, very little was published overall about McCarver’s proposed segregation law. Most of the newspapers in the state featured content from either the Associated Press or United Press and offered no commentary pertaining to the Junior Rose Bowl, often publishing a brief summary of the day’s legislative happenings and identifying the potential law only by its docket number, HB 47.16 Even United Press’s Mississippi bureau chief John Herbers, who has been noted by historians for his groundbreaking coverage on the civil rights movement, neglected to make the proposal the focal point of his account, identifying it in the eleventh paragraph of his story, which was published in the January 19, 1956, edition of the Delta Democrat-Times.17 Other noteworthy newspapers, such as the Jackson State Times, the Commercial Dispatch, the Jackson Advocate, and the Hattiesburg American, failed to publish anything on the potential law.

While the bill was introduced on the floor of the Mississippi House of Representatives, McCarver’s proposed law made it no further. Undaunted, the political elite in the state banned together with the Board of Trustees for Institutions of Higher Learning, also known as the State College Board, in a private meeting to create a segregated standard in state collegiate athletics that would prevent a repeat of JCJC’s challenge to the Closed Society.18 The state and its educational institutions began to acknowledge the ban as the “unwritten law,” a gentleman’s agreement that all-white teams in the South would abstain from playing integrated teams from the North.19 Any violation of the agreement would result in a one-year prison sentence for the offending school official, a fine of $2,500, and the loss of state funding.20 While the law did not actually exist, Mississippi legislators and the State College Board enforced it anyway, threatening to withdraw funds from schools that violated the agreement.21 Verifying the secretive nature of political dealing in the Closed Society, none of the newspapers examined in this volume published an article on the creation of the unwritten law. Furthermore, there is no record of the State College Board hearing the proposed gentleman’s agreement and of its eventual acceptance. The first challenge to the unwritten law would emerge less than a year later.

It has long been customary for college basketball teams to participate in holiday tournaments in December. In the case of both Mississippi State College22 and the University of Mississippi, the 1956 Evansville Invitational Basketball Tournament and All-American Holiday Tournament were to be barometers for the teams’ upcoming Southeastern Conference schedules. The Maroons were led by standout center Jim Ashmore, who averaged 27.4 points per game, and Bailey Howell, who led the nation in rebounding and averaged 26.4 points per game. The State contingent had won six of its first seven games going into the Evansville tournament and was slated to play the University of Denver Pioneers in the first round on December 28, 1956. The Maroons defeated the Pioneers 69–65 behind the play of Howell, who scored twenty-two points. The Denver squad closed to 67–65 with eighteen seconds left, but Ashmore scored two of his twenty points in the final seconds to give the representatives from the Magnolia State the win. However, what appeared to be just another basketball game had great significance within the ideological borders of the Closed Society, as the Pioneers carried two blacks on their roster, Billy Peay and Rocephus Silgh, making the contest the first integrated game for Mississippi State in the school’s history. Despite their presence, neither Peay nor Silgh had an impact on the outcome of the game. Silgh scored only two points and Peay did not play.23 The repercussions of State’s violation of the unwritten law were swift, both displaying the power of Mississippi’s segregationist beliefs and setting the stage for the enforcement of the gentleman’s agreement for years to come.

After the game, it was announced that the Maroons would leave the tournament before their game against Evansville College because of the integrated presence of the already defeated Pioneers.24 Many newspapers were initially unaware of the integrated status of the Denver squad, as the Jackson State Times, the Clarion-Ledger, the Delta Democrat-Times, and the Meridian Star all published December 29, 1956, accounts of the victory without referencing Mississippi State’s exodus. The Clarion-Ledger even published a photograph of Howell from the MSC-Denver contest, seemingly unaware that two black players wore Denver uniforms.

The state newspapers depended primarily on wire accounts from the Associated Press and United Press when it came to the coverage of the Maroons’ exit from the tournament. The Jackson Daily News was the first newspaper to publish an article on the Maroons’ history-making contest on December 29, 1956, proclaiming that “racial barriers broke down for a Southern school in athletic competition.” MSC president Ben Hilbun told the unknown reporter that he was surprised by the presence of blacks at the tournament: “If we had known that the Denver team had Negroes, our team would not have been there to play the game.” Head coach James “Babe” McCarthy, who would become a central figure in State’s battles with the unwritten law, declined comment.

It was Mississippi State President Ben Hilbun who was often shouldered with the burden of deciding the basketball team’s fate when it came to playing integrated teams. Publicly, Hilbun told the press it was his decision for the Maroons to leave the integrated Evansville Invitational Basketball Tournament in 1956 and would make similar admissions during subsequent challenges to the unwritten law while Mississippi State was under his administration. Courtesy Mississippi State University Libraries, University Archives.

The rest of the state’s newspapers seemed to get wind of MSC’s tournament exit and published similar accounts on December 30, 1956. The Daily News would later claim that the Maroons won the contest “in spite of the presence of black players,” making a clear editorial statement in the confines of a news article. Questionable editorial decisions continued to plague the Hederman-owned newspapers as both the Daily News and the Clarion-Ledger published an Associated Press article on MSC’s withdrawal from the tournament on its front pages on December 30, 1956, and, in the process, presented an interesting dichotomy of race issues in the South. The first part of the article went into detail about the MSC-Denver contest and the Maroons’ subsequent exit from Evansville. It was reported that MSC athletic director C. R. “Dudy” Noble made the decision to remove the team from the tournament, free of influence from the state legislature. “It has always been our policy that our teams would not compete with Negroes,” Noble explained. “That’s tradition with our institution. There is no rule here; it is just a matter of policy and tradition. It is the way we have always operated.” However, in a stark topical switch, the article also discussed a dynamite explosion at the Citizens’ Council headquarters in Clinton, Tennessee, in which no one was hurt. The peaceful withdrawal of the MSC contingent was balanced with the violent incident at the Citizens’ Council headquarters, an organization to which both the editor and owners of the Jackson Daily News and the Clarion-Ledger ...