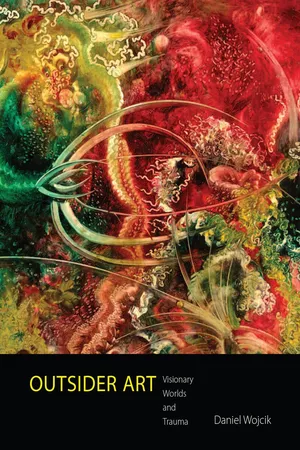

![]()

Chapter 1

Inside the Art

of Outsiders

On Formalism, Biography,

and Cultural Milieu

During the past three decades, the phenomenon of outsider art has moved from the margins of cultural awareness toward the mainstream of the contemporary art world, captivating an international community of collectors, curators, dealers, scholars, and artists, as well as the general public. Often characterized as “raw art” that is created spontaneously and for entirely personal reasons, outsider art historically has been associated with individuals who have no formal artistic training and exist outside of the dominant art world—psychiatric patients, visionaries and trance mediums, self-taught individualists, recluses, folk eccentrics, social misfits, and assorted others who are isolated or outcast from normative society, by choice or by circumstance.

The allure of outsider art has spawned an industry of galleries, publications, museum exhibits, art fairs, and auctions. The community of outsider-art aficionados itself has been the subject of ethnographic study and journalistic exposé.1 A canon of classic outsiders and visionaries has been established, and grants, commissions, and international awards routinely recognize and reward outsider artists. Their work has penetrated popular culture, adorning postage stamps and rock-and-roll album covers, and outsider artists have been depicted in musical scores and off-Broadway shows. Their creations have been enthusiastically embraced by A-list artists, musicians, actors, scholars, and celebrities from Pablo Picasso, Paul Klee, Max Ernst, and Jean Dubuffet, to David Bowie, Leonard Nimoy, Robin Williams, Susan Sarandon, Jane Fonda, Jonathan Demme, Tommy Lee Jones, John Waters, and Bjork. Films about outsiders and visionaries have received critical acclaim, such as Séraphine (2008), In the Realms of the Unreal: The Mystery of Henry Darger (2004), and Junebug (2005).2 Even Homer Simpson is celebrated as an outsider artist after his failed attempt to build a backyard barbeque pit, a disaster of metal parts stuck in cement, is discovered as a masterpiece by an excited gallery owner who informs him, “Outsider art couldn’t be hotter!”3 The outsider category has now extended to other expressive forms as well, including the off-beat music by self-taught individuals such as underground cult luminaries Hasil Adkins, Daniel Johnston, Lucia Pamela, the Shaggs, Wesley Willis, and Lonnie Holley, among others.4

With the opening of the Museum of Everything in London in October, 2009, advertised as “a space for artists and creators outside modern society,” the art of self-taught outsiders achieved a new and trendy level of recognition. More than three-quarters of a million people have visited this travelling venue of creative exhibits, with its homespun, hipster vibe and inventive collaborations involving an entourage of artists, collectors, and celebrities including Cindy Sherman, David Byrne, Maurizio Cattelan, Ed Ruscha, Damien Hirst, Sir Peter Blake, Pete Townshend, Nick Cave, John Zorn, and Annette Messager.5 At the 55th International Art Exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 2013, the work of self-taught and outsider artists had a dominating presence, and the Museum of Everything’s official affiliated exhibition of such art was a popular attraction. The director of the Biennale, Massimiliano Gioni, integrated outsider art into the show, exhibiting it alongside that of formally trained artists. The main exhibit was entitled Il Palazzo Enciclopedico (The Encyclopedic Palace), in honor of the self-taught Italian-American artist Marino Auriti (1891–1980), the working class owner of an auto body shop in the town of Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, who in his spare time constructed a sculptural prototype for a massive imaginary museum, meant to be the tallest building in the world and contain the history of all worldly knowledge, from the wheel to the satellite. The Biennale’s outsider-art emphasis made international headlines, with many commentators considering the event one of the best art exhibits in recent years and applauding its infusion of non-mainstream and outsider art into international art-world sensibilities as an overt challenge to the commercialization of contemporary art.6 New York Times art critic Roberta Smith proclaimed that 2013 “was the year that outsider art came in from the cold,” and that increasing recognition of the importance of outsider art could be seen in recent acquisitions of major outsider-art collections by institutions such as the American Folk Art Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Milwaukee Art Museum, as well as influential exhibits of outsider art internationally (Smith, 2013).

No longer a rogue genre, outsider art commands attention more than ever before, having captured the popular imagination as a form of unharnessed and pure creativity. In turn, both the public and the market have embraced the notion of an “authentic art” that provides an alternative to the elitism and commercialism of the professional contemporary art world. John Maizels, an authority on the subject and the editor of the influential Raw Vision magazine posits, “It is no coincidence that the growing stature and influence of Outsider Art has happened over a period when the esteem of professional contemporary art has been held increasingly in question. The great avant-garde movements have faded into history and many feel they are faced today in our museums and galleries with an art which has become increasingly obscure and inaccessible.” Maizels further suggests, “It is no wonder that an art with immediate appeal and immediate responses, that needs little critical explanation to be fully appreciated, an art that has real meaning, that stems from the roots of genuine creativity, that is forever innovative and original and truly reflects the individuality of its host of creators, cannot fail to touch an increasing and appreciative public” (1996: 228).

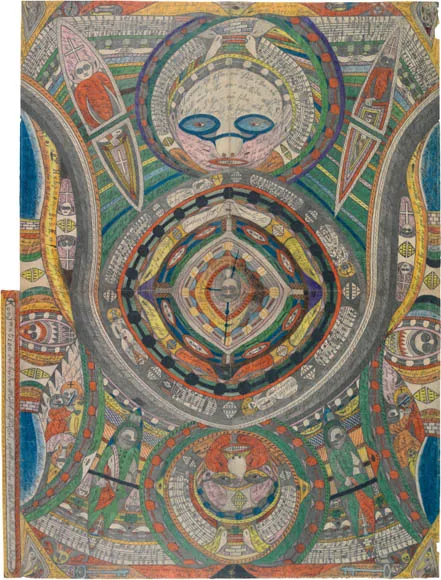

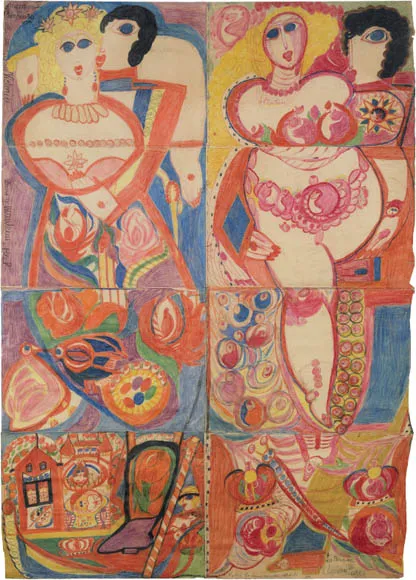

Adolf Wölfli, Giant City, Band-Wald-Hall, 1911. In From the Cradle to the Grave, Book 4, p. 213. Pencil and colored pencil on newsprint, 39 ¼ x 28 ¼ in. (99.7 x 71.7 cm). Courtesy Adolf Wölfli Foundation, Museum of Fine Arts, Bern, Switzerland.

Even as this widespread fascination with art created outside the structures of the art world flourishes, the definition of outsider art remains elusive. The term itself is the subject of ongoing debate, promoted by some dealers and critics as a valid category, rejected by others as a deeply offensive concept, and often embraced in resignation for lack of a better word, or conflated with other terms such as “self-taught art,” “visionary art,” “art singulier,” “autodidact art,” “naïve art,” “idiosyncratic art,” or “contemporary folk art.” Adding to the confusion, the concept of outsider art has different and very specific associations in Europe, where such art was initially identified and studied. In the United States, the awareness of outsider art is relatively recent. In the European context, outsider art is equated with art brut, a term that refers to works created by people with no artistic training, who are somehow disconnected from conventional culture and outside the art world, such as the mentally ill, trance mediums, self-taught isolates, and societal outcasts. Their work has been celebrated as unique, idiosyncratic, and seemingly without precedent. In the States, by contrast, dealers and critics often use the term outsider art loosely, in reference to a melange of non-mainstream works created by a varied demographic: untrained artists, children, inmates, contemporary folk artists, naïve artists, artisans from so-called Third World and developing nations, and members of specific ethnic groups. As a result, definitions of outsider art are unstable and contested, and “term warfare” has been waged on numerous occasions. Still, the concept of outsider art thrives as a term of convenience, a catchall signifier and marketing label for art outside the mainstream.7

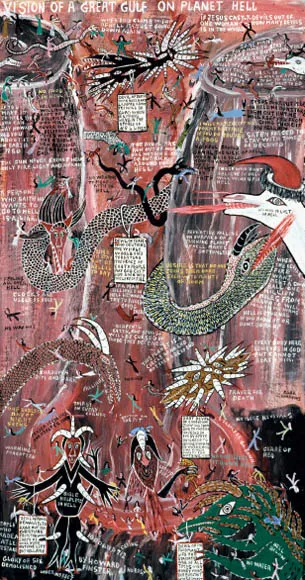

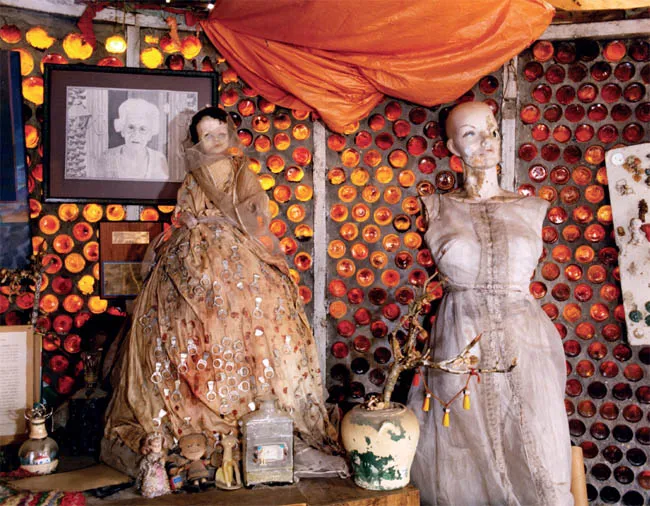

Surveying the field of outsider art today, one encounters an astounding assortment of drawings, paintings, sculptures, embroidery, carvings, art environments, assemblages, and other artworks. This plethora of creative output is produced outside of the fine art echelons by a wide range of individuals. Some were diagnosed as mentally ill, such as the highly acclaimed Adolf Wölfli, Aloïse Corbaz, August Natterer, Martín Ramírez, and Carlo Zinelli. Others were inspired by religious experiences, dreams, or trance states, such as the Spiritualist mediums Madge Gill and Augustin Lesage, the apocalyptic visionaries Howard Finster and Sister Gertrude Morgan, or the Haitian Vodou practitioners Hector Hyppolite and Pierrot Barra. The work of self-taught southern African Americans is ubiquitous in the outsider-art world: Bill Traylor, Minnie Evans, Bessie Harvey, Thornton Dial, William Edmondson, James “Son” Thomas, Sam Doyle, Royal Robertson, Purvis Young, Mose Tolliver, and Lonnie Holley are just a few of the many highly regarded artists. Individuals who have constructed entire art environments also have been included in the outsider and visionary art category: Sabato (Simon) Rodia and his Watts Towers in Los Angeles; Ferdinand Cheval’s Palais Idéal and Raymond Isidore’s La Maison Picassiette in France; Nek Chand’s Rock Garden in Chandigarh, India; Helen Martins’s Owl House in Nieu-Bethesda, South Africa; Grandma Prisbrey’s Bottle Village in Simi Valley, California; and Richard Greaves’s anarchitectural structures, hidden in the countryside of Quebec. And then there are those who defy categorization, such as James Castle, James Harold Jennings, Alexander Lobanov, Luboš Plný, Ionel Talpazan, Melvin Way, and George Widener, among many others.

Madge Gill, The Crucifixion of the Soul (detail), commenced June 1, 1934. Black and colored inks on calico, 1 ⅞ x 17 ¼ feet (56 cm x 5.25 meters). Image and dimensions courtesy London Borough of Newham Heritage and Archives.

Howard Finster, VISION OF A GREAT GULF ON PLANET HELL, 1980. Enamel on plywood with painted frame, 35 ⅜ x 18 ⅝ in. (90 x 47.2 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum; gift of Herbert Waide Hemphill, Jr. (1988.74.5).

Sabato Rodia’s towers in Watts, California. Photograph Seymour Rosen, May 1991. Courtesy SPACES—Saving and Preserving Arts and Cultural Environments.

Ferdinand Cheval’s Palais Idéal, Hauterives, France. Photograph Emmanuel Georges. Copyright Collection Palais Idéal, Emmanuel Georges.

Unlike folk art, which is rooted in collective aesthetics and in the traditions of a particular community or subculture, outsider art is usually considered to be an expression of a uniquely personal vision that preoccupies the creator, who is often regarded as disconnected from the broader culture or community.8 Most of the literature about outsider artists portrays them as self-taught individuals who create things with no regard for recognition or the marketplace. As described by Michel Thévoz, author of the book Art Brut and the former curator of the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, outsider art “consists of works produced by people who for various reasons have not been culturally indoctrinated or socially conditioned. They are all kinds of dwellers on the fringes of society. Working outside the fine art ‘system’ (schools, galleries, museums and so on), these people have produced, from the depths of their own personalities and for themselves and no one else, works of outstanding originality in concept, subject and techniques. They are works which owe nothing to tradition or fashion. . . . [These artists] make up their own techniques, often with new means and materials, and they create their works for their own use, as a kind of private theater. They choose subjects which are often enigmatic and they do not care about the good opinion of others, even keeping their work secret” (Thévoz, no date). Outsider art also has been defined by its qualities of originality and intensity, and described, often in breathless prose, as a truly inventive form of art that is “potent, evocative, provocative, intensely personal, unselfconscious, expressive, enigmatic, obsessive, vital, disquieting, brutal, subtle, exotic, close-to-the-ground, challenging” (David Steel, quoted in Manley, 1989: ix).9

Inside one of the structures at Tressa Prisbrey’s Bottle Village in Simi Valley, California, early 1990s. Photograph Ted Degener.

Richard Greaves’ anarchitectural house construction in a forest in Quebec, 2008. Photograph Peter Jan Margry and Daniel Wojcik.

Aloïse Corbaz, Napoleon III at Cherbourg (The Star of the Paris Opera), (Napoléon III à Cherbourg [L’étoile de l’Opéra Paris]), between 1952 and 1954. Colored pencil and juice of geranium on sewn-together sheets of paper, 64 ½ x 46 in. (164 x 117 cm). Photograph Claude Bornand. Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne.

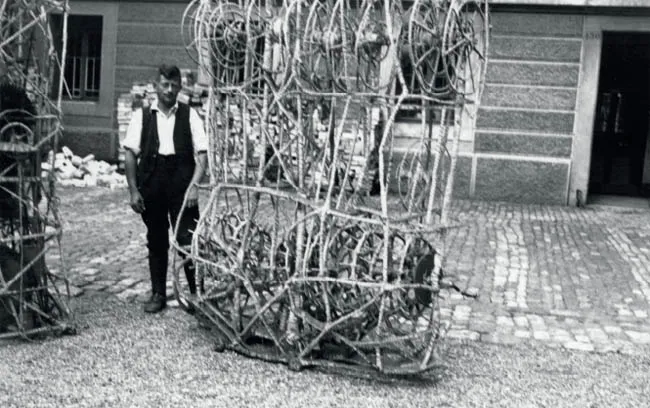

Heinrich Anton Müller, with machines he invented (whereabouts unknown), in the courtyard of the Münsingen Asylum, near Bern, Switzerland, c. 1914–1922, © Kunst-museum Bern, Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie.

The category of outsider art was not created by artists themselves, nor should one consider outsider art an artistic style or historical movement like Cubism, Dada, Surrealism, or Abstract Expressionism. Instead, it is a classification that has been defined and imposed upon individuals by collectors, art critics, and dealers. Those who have been labelled outsider artists seldom have contact with each other, and usually have little interest in defining their own work in such terms. Many so-called outsiders do not consider themselves artists at all, and they often make things for entirely personal reasons, whether in response to a traumatic event, for instance, or as an expression of a visionary experience. Such works, often created by individuals with no thought of financial gain or personal acclaim, have increasingly been introduced by others into the high-stakes realm of the professional art world, and may sell for tens of thou...