![]()

Part I

THEORETICAL TERRAIN

![]()

1

An Analytic Model of Conflict and Cooperation on the Terrain of Race

ROBERT S. CHANG

In this chapter, I explore conflict and cooperation between and within minority communities. I begin by offering an analytic model for understanding conflict and coalition on the terrain of race. I then discuss racialization and racial stratification. I conclude by discussing the limits of building coalitions in a purely oppositional mode and explore the need for building common cause that extends beyond opposition to white capitalist patriarchy.

Against the backdrop of conflict between members of minority communities, white supremacy often gets lost. Despite calls by scholars such as Charles Lawrence to talk about racism in terms of white supremacy,1 there is a tendency in scholarship on race to focus on what I describe as first-order binary and second-order binary analyses.

In this analytic model of first-, second-, and third-order racial analyses, the first-order binary model restates the duality of the primary racial opposition in US history—black and white—and recognizes that many analyses of racial and ethnic conflict follow this basic majority-minority binary opposition. Commentaries and analyses that focus upon majority-minority relations are first-order binary analyses.

There is nothing wrong with such scholarship unless it purports to constitute the entire analysis of the way racism works to subordinate all groups. For example, too great a focus on the relationship between whites and blacks can lead to pushback in the form of a critique of such scholarship. Such a critique typically includes two components: a critique of the black/white paradigm as incomplete, which may then provide the space for the analysis of the relationship between the dominant group and minority B.2 Though a second (or third or fourth) minority group has been introduced, I would still describe this as a first-order binary race analysis, and in the aggregate, as multiple first-order binary analyses.3

Second-order binary analysis stays within a group-to-group binary framework, but looks at the relationship between minority A and minority B. Scholarship using a second-order binary analysis might include rudimentary comparative racialization, a comparison of the similarities and differences between minority A’s and minority B’s experience with oppression.4 Sometimes this comparison is characterized as or in fact devolves into a squabble between minority A and minority B over which group is the most oppressed.5 An example of the former is the one that reportedly took place on President Clinton’s national commission on race between John Hope Franklin and Angela Oh over the scope of their investigation. It was reported that Oh commented, “We need to go beyond [black-white relations in America] because the world is about more than that,” to which John Hope Franklin responded, “This country cut its eyeteeth on black-white relations.”6

Mari Matsuda’s description of what took place is helpful: “There is a reason why historian John Hope Franklin’s admonition that we must learn the history of white over black is seen as oppositional to Angela Oh’s admonition that we must remember the unique issues facing a largely immigrant Asian American community. As long as the mainstream press can frame this as an opposition, it can deflect discussion from the core issue of white supremacy.”7 The lesson is that care must be taken when doing second-order binary analysis not to lose sight of the larger political, legal, and social forces that foster conflict between minority groups. In the American context, one must never lose sight of white supremacy.

Another example of second-order binary analysis comes from Tanya Hernandez, commenting on racial violence between Latinas/os and African Americans that is “acrimonious” and “growing hard to ignore.”8 We are told that there is a trend of “Latino ethnic cleansing of African Americans from multiracial neighborhoods.”9 We hear of a “black-versus-Latino race riot at Chino state prison.”10 She appears to engage in second-order binary analysis to try to understand the conflict between Latinas/os and African Americans in Los Angeles. Her title, “Roots of Latino/Black Anger: Longtime Prejudices, Not Economic Rivalry, Fuel Tensions,” gives away her punch line. Though mindful of other explanations—labor market competition, tensions arising from changing demographics in neighborhoods, Latinos “learning the U.S. lesson of anti-black racism,” or resentment by blacks of “having the benefits of the civil rights movement extended to Latinos”11—she locates the roots of anti-black racism among Latinos in Latin America and the Caribbean.12 While I agree with her conclusion that minority groups must address their own racism, I also agree with Taunya Banks, who in the context of black-Asian relations stated that the “[r]enunciation of simultaneous racism alone, however, will not foster racial coalitions between Asians and Blacks.”13 Further, I worry that the big picture, how the relationship among minority groups is structured by white supremacy, might be lost.

Trying to understand, avoid, exploit, or resolve such conflicts can lead to what I call third-order multigroup analysis. I want to emphasize here that any of these analyses, including third-order multigroup analysis, can serve subordination or antisubordination efforts. I set forth how an understanding of racialization and racial stratification lends itself to third-order multigroup analysis.

With regard to Asian Americans, Yen Le Espiritu offers the notion of panethnicity as a way to theorize an Asian American group that arises out of multiple ethnic or national origin subgroups.14 She develops this theory of panethnicity against the background of sociological theories of ethnicities.15 Panethnic Asian Americanness is offered as an oppositional identity that is a product of discrimination but which includes a political aspiration, offering its members some instrumental benefits, including what comes from being part of a larger group. One limitation, though, is that she does not develop themes of black-Asian conflict or coalition in this work. She notes at the beginning a possible comparison of Asian Americans and other groups—Latinas/os, Native Americans, and African Americans—but the comparisons are not developed. Further, comparison is complicated because the relationship between panethnicity and race is not worked out. I would characterize this work as being a first-order binary analysis. As with many first-order binary analyses, it is excellent for what it does, but is limited with regard to what it can tell us about the relationship of multiple groups in racially stratified America.

Neil Gotanda has developed a theory of Asiatic racialization that adapts and modifies ethnic categories and existing understandings of black-white racialization.16 An examination of the federal and Supreme Court cases in the era of Chinese exclusion reveals that the federal courts modified their understanding of the Chinese category. After initially considering “Chinese” as a term of national origin or national citizenship, Congress definitively adopted a racial understanding—“Chinese” refers to any person of Chinese ancestry—a form of bloodline categorization. To that category, however, foreignness—a permanent condition of inassimilability and disloyalty—becomes the primary racial trait. Foreignness was the assigned racial trait or racial profile rather than any notion of biological or cultural inferiority. The basic method of legal analysis—finding foreignness embedded in judicial decisions and other legal materials—has been developed by other authors writing on Asian Americans and the law.17

While this theory of Asiatic racialization by itself is first-order binary, this model is explicitly intended to provide a common language of racialization that permits a comparative analysis around white supremacy. Because the Chinese category is racialized and the primary attribute of foreignness is assigned to the Chinese-Asiatic body, this racialization is similar to historical black-white racialization. The structurally similar bases for racialization offer a theoretical basis for building racial coalitions. As an immediate political platform, such an analysis does not provide immediate common interests as a basis for coalition. But a presentation of foreignness as a racial profile inscribed on Asiatic bodies does provide the beginnings of a common language of racialization that is then available for antiracist politics, something that panethnicity does not do. On the contrary, panethnicity has the danger, like other ethnicity theories, of being organized around a common language of assimilation.18

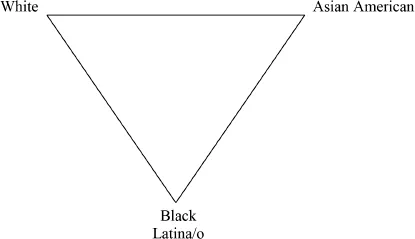

Assimilation is the great promise offered by proponents of the model minority designation for Asian Americans. Thinking through it as a multigroup analysis may offer some theoretical clarity. Here, the idea of racial triangulation holds much promise, especially as advanced by Claire Jean Kim, a political scientist. Her work on black-Korean conflict developed a mapping of blacks, Asian Americans, and whites against two axes—Superior-Inferior and Foreigner-Insider.19 In this model, whites hold the most privileged position along the Superior-Inferior axis and a coequal position as insiders with blacks on the Foreigner-Insider axis. In contrast, blacks hold the least privileged position along the Superior-Inferior axis, while Asian Americans hold a middle position along the Superior-Inferior axis and the least privileged position as foreigners on the Foreigner-Insider axis. Central to Kim’s project is the attention paid to the relationship between blacks and Asian Americans in relation to the white position.

Racial triangulation in the form of inverted triangles can help us to understand the following three examples of third-order multigroup analysis. Depending on the issue, a different group is placed on a horizontal plane of formal equivalence with whites. The triangle is a useful device to emphasize the issues at stake in the coalition and helps to avoid collapsing the politics into a false binary. The triangulation diagram demonstrates the issue-specific way that the invitation to whiteness (actual, honorary, or formal) or Americanness is issued, and highlights the inconsistencies and the hypocrisies.

Example 1—Asian Americans as a Model Minority or “Honorary” Whites

William Petersen, the Berkeley, California, demographer who is credited with coining the phrase “model minority,” offered the success of Japanese Americans, who overcame the hurdles of racism through their hard work and culture, as a model for “non-achieving” blacks and Chicanos.20 Petersen’s efforts were directed against Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs. More recently, Asian Americans were inserted into the debate over affirmative action as a model minority in coalition with whites and therefore in opposition to blacks and Latinas/os.21

Figure 1.1. Asian Americans as a model minority.

As discussed earlier, Asian Americans are invited to join whites along a common horizontal plain, in opposition to blacks and Latinas/os at the bottom point of the inverted triangle. Neoconservative politicians and thinkers advocate for the rights of Asian Americans as victims of affirmative action policies, thus insulating themselves from charges of racism for their opposition to affirmative action. Using Sumi Cho’s term, Asian Americans beco...