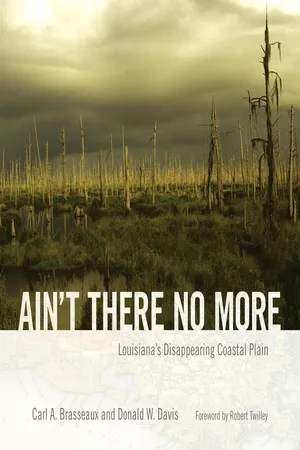

![]()

Dying/dead vegetation provides stark evidence of the ecological changes now occurring in Louisiana’s coastal zone. These changes directly threaten the local residents’ traditional way of life. (Photo by the authors, 1989)

1

MESSIN’ WITH MOTHER NATURE

During the past fifty years great changes have taken place in this State due to man-made factors which are changing the conditions of existence for our wild life and fisheries from its very foundations. Perhaps the most significant of these is flood protection in the valley lands of our rivers by means of levees which render the front lands and considerable areas of the back lands reasonably free from annual floods.… The situation has further been exaggerated by the fact that Louisiana has also to bear the brunt of the burden due to flood protection, drainage and deforestation going on in the entire area of 1,325,000 square miles of the Mississippi valley.

Source: P. Viosca, “Louisiana Wet Lands and the Value of Their Wild Life and Fishery Resources,” Ecology 9(2) (1928): 221–222.

South Louisiana’s physical landscape is remarkably young, its history comprising mere milliseconds on a geologic time line. The region’s complex mélange of land, mud, and water is a direct product of the notorious volatility, bifurcating tendencies, and sedimentation patterns of the Mississippi River and its associated deltas over the course of recent millennia. In studying the Holocene sediment history of the Mississippi River’s drainage basin (the world’s fourth largest), coastal geomorphologists have divided Louisiana’s organic lowlands into the Chênière (often Anglicized to Chenier) and Delta Plains. In southwest Louisiana, each chênière (ancient beach ridge with an average elevation of about six feet) is perched on a muddy substratum. These marsh ridges constitute part of an archipelago of inland “islands”—collectively referred to as the Chênière Plain—each marking the position of a once-active ancient shoreline. These primeval beaches are a product of the Mississippi’s prehistoric meanderings. When the river occupied its westernmost prehistoric course, littoral currents carried clay, mud, and sand westward, advancing the Chênière Plain as a mud coast in the Louisiana and Texas lowlands west of Marsh Island. Interruptions in the progradation process allowed coarser particles to accumulate, forming a ridge. The increase in sedimentation also caused the shoreline to advance, leaving behind conspicuous chênières as the region’s most impressive and distinctive topographic features. These relatively rare natural phenomena—scattered across the southwestern marshes—provide residents of the coastal wetlands with a modicum of “high”-ground protection against hurricanes.

The Delta, or Deltaic Plain, lies east of Marsh Island. This region consists of alluvial material deposited over the past 7,500 years by the Mississippi River as a by-product of its dynamic confrontation with the Gulf of Mexico. The river’s headlong collision with the Gulf Stream results in a rapid loss of the freshwater current’s velocity and the attendant jettisoning of its suspended heavy sediment load. Sustained deposits gradually form sedimentary lobes, and accretion broadcast over a broad geographic area resulting from the sporadic migration of the Mississippi’s channels over centuries created a sprawling wetland stretching from the Atchafalaya River to the Rigolets. The Deltaic Plain’s salient features include a highly irregular shoreline with associated rivers, natural levees, marshes, swamps, bayous, lakes, barrier islands, and salt domes.

Wetland loss stems in part from engineering efforts to tame the once unfettered Mississippi in response to settlers’ outcries for relief from the very flooding responsible for creation and maintenance of the lands upon which they lived. This system of earthen bulwarks has harnessed and trained the great river’s distributaries to follow an unnaturally narrow, designated route to the Gulf.

From the beginning, efforts to channelize the Mississippi River were fraught with problems. Levee systems were originally constructed and maintained by landowners. Following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the federal government demonstrated no interest in flood protection; however, Reconstruction-era floods (1862–1877) and unprecedented damage from the inundations of 1882, 1892, and 1927 forced Congress to become proactive in flood management. Beginning in 1928, the national government built—at a cost of $5.8 billion—the present “guide levee” system, which produced short-term economic benefits at the expense of long-term, perhaps irreparable environmental costs. Critical nutrients and sediments no longer reached dependent ecosystems, and saltwater consequently began to intrude into formerly flourishing brackish, intermediate, and freshwater habitats, slowly destroying them.

The disruption of the coastal region’s natural hydrological plumbing also compounded the problem of environmental damage wrought by major navigational channels and oil and gas exploration in the twentieth century. In the 1930s the focus of Louisiana’s oil industry shifted from the state’s northern parishes to the coastal zone, particularly the coastal marshes, where remote drilling sites were typically accessible only to barge-mounted rigs. Between roughly 1930 and the turn of the twenty-first century, oil companies dredged canals to serve the approximately 67,000 completed wells in the coastal wetlands and additional canals to accommodate pipelines transporting oil and gas to processing and distribution facilities in the interior. Canals destroyed the integrity of the coast’s prairies tremblants, facilitated erosion by allowing tidal action to work on fragile wetland environments, and permitted greater saltwater intrusion to destroy indigenous grasses that were essential to the marshes’ well-being. Finally, spoil banks resulting from dredging activity disrupted what little natural hydrology remained.

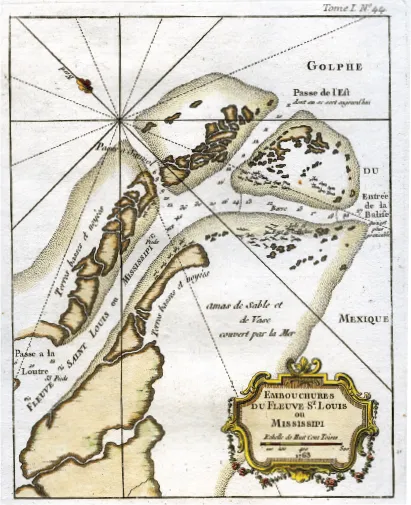

Published in Paris in 1763 by the cartographer J. N. Bellin, this map shows the primary navigation channel, with depth soundings, for waterborne commerce into and out of the Mississippi River. Tiny illustrations on the maap show the accumulation of logs washed down and lodged in the silt deposits of shallow waters, as well as the location of the delta community of Balize. (From the authors’ collections)

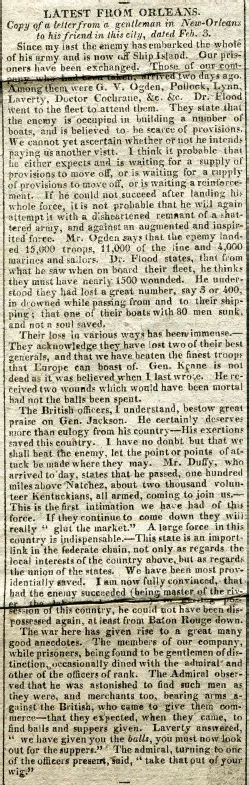

The Battle of New Orleans (January 8, 1815), fought in Louisiana’s coastal wetlands, preserved the United States’ control of the Mississippi Valley. (New York Herald, March 8, 1815)

The Mississippi River Basin. (Map compiled and edited by Lisa Pond, cartographer)

Every successive Mississippi delta that contributed to the formation of the modern Deltaic Plain underwent several predictable stages of development. Over time, the gradient and carrying capacity of the lower river gradually decreased, and a shorter route to the sea eventually “captured” the main channel’s flow. A diversion occurred, and the new course caused a shift in the location of the active delta’s sedimentation regime. This shift left the old channel and delta to “die” and become yet another building block in Louisiana’s burgeoning coastal wetland.

In active deltas, distributaries—watercourses drawing water away from the trunk channel—provided the mechanism for advancement of the principal lobes and sublobes into the shallow waters of the continental shelf. Distributaries inevitably branched and subdivided, thereby accelerating the distribution of river-borne sediments within the coastal lowlands. Most contemporary authorities identify five mature Holocene delta complexes (Maringouin/Salé/Cypremort, Teche, St. Bernard, Lafourche, and Balize), while a sixth (Atchafalaya–Wax Lake) is in an early stage of development. The new landmasses created at rivers’ mouths frame, protect, and shelter associated deltaic estuaries and wetlands. These geographical features are the Gulf Coast’s first line of defense against all storm events, from minor squalls to wave action linked to cold fronts, to hurricane storm surges, to ongoing marine processes such as saltwater intrusion, tidal currents, and sediment transport.

The Mississippi’s peripatetic quest for the steepest available outlet gradient has produced distinctive near-sea-level topographic features that are changing at varying rates tied individually to localized sedimentation cycles. These cycles consist of alternating periods of retreat and advance resulting from relative rises and declines in sea level. These evolutionary cycles are predictable—older deltas deteriorate faster than younger ones. This is seen most clearly in the Mississippi Delta. While the river’s bird-foot delta is in rapid retreat, one of the world’s fastest-growing deltas is expanding at the mouth of the Atchafalaya Ri...