![]()

PART ONE

The Next President of the United States

![]()

1

I’M NOT GEARED TO TOTAL ACCEPTANCE

A canopied entrance off Madison Avenue leads to one of New York’s most intimate concert venues, a place where time has seemingly stood still for more than half a century. To the left of a small foyer is the Bemelmans Bar, its walls covered with fanciful scenes of Central Park as rendered by Ludwig Bemelmans, the celebrated author of Madeline. Jazzy standards fill the air, listeners scattered among nickel-trimmed tables and perched like placid crows at the black granite bar. It’s as civilized a spot as exists on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, the sort of room where the conversations come accessorized with dry martinis and the gimlets are mixed with fresh lime.

Opposite the Bemelmans is a shrine to the art of cabaret, a performance space only slightly larger than a regulation racquetball court. Here is where musical acts as varied as Herb Alpert and Eartha Kitt have held forth, and where Bobby Short was seasonally featured for thirty-six years. On its walls are the murals of Marcel Vertès, the Academy Award–winning designer of Moulin Rouge, its blue-hued banquettes encircling a floor still dominated by a grand piano.

Although Short, whose portrait hangs just outside, liked to refer to himself as a saloon singer, the Café Carlyle has never been the province of comedians. When Woody Allen sits in with the Eddy Davis New Orleans Jazz Band, he sticks to his clarinet and never utters a word. So of all the people who could possibly be booked into this elegant little sanctuary on a Monday night, one of the most unlikely is the man who single-handedly made the stage safe for an open collar, a jazz artist who can neither sing nor play an instrument, a satirist so savage that Time once described him as “Will Rogers with fangs.”

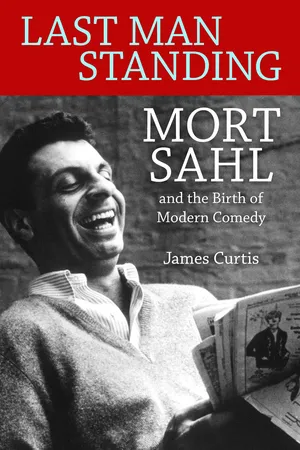

Seated at a table near the back, Mort Sahl doesn’t appear nervous in the least. Clad in a red cashmere sweater, he is still strikingly handsome at age 86, the celestial nose suggesting the profile of a much younger man, the graying hair at once both combed and unruly. He chats comfortably as the room fills, quick to break into a grin as if some private absurdity has just caught his attention. Occasionally a stranger leans in to shake his hand; one man asks him to sign a copy of his book Heartland and tells him that he’s been a fan for fifty years.

Among those taking their seats are James Wolcott, cultural critic and blogger for Vanity Fair; the comedian Mark Pitta; broadcast journalist John Hart; and the star’s third wife, Kenslea, who has flown in from California expressly for the occasion. At 10:50, Dick Cavett makes his way to the riser as applause fills the room.

“Some years ago,” he says by way of introduction, “a meteor shot across the comedy sky. My new friend Woody Allen and I went to see him at a place called Basin Street East in New York. Woody said, ‘Wait until you see him. You will agree with me that everyone else should quit the business.’ Here is a man who said: ‘Ronald Reagan won because he ran against Jimmy Carter—and if he had run unopposed he would have lost.’

“Once at Basin Street a guy yelled out, ‘Is that a Brooks Brothers sweater?’ So Mort picked up the subject of Brooks Brothers and said, ‘It’s a strange store. They have no mirrors, but they will stand another customer in front of you.’

“That’s a bit of a weird curve,” he admitted over the appreciative laughter, “but I love weird curves …

“Ladies and gentlemen, the great Mort Sahl.”

Prolonged applause as Sahl moves slowly toward the stage, his friend Lucy Mercer at his side, his balance uncertain after a 2008 stroke robbed him of the sight in one eye. “Thank you,” he says when firmly in place, a pair of newspapers clutched in his right hand. “I want to tell you that Barack Obama has taken a reverse mortgage out on the White House.”

The laugh builds as the thought sinks in.

“The old saying was that if anything happened to the president, the Secret Service had standing orders to shoot Joseph Biden …”

More laughter.

“This is not going to be a political show tonight. I’d like to talk about a couple of other subjects I know something about—men and women. Politics are getting harder because the Democrats don’t know how to make their comeback. They’re already apologizing for this guy and promising you Hillary Clinton.… She rose through the ranks—slept with the boss. Or didn’t sleep with the boss.… Okay, Lady Macbeth.”

Sizing up the room, he seems caught in a perpetual state of amusement. His blue eyes glow as if electrified. He flashes a gleaming set of teeth as would an animal on the verge of attack.

“I brought two papers for you tonight,” he announces. “One is the New York Times because of the nature of the people who patronize this hotel, and one is the Post, which they hide behind it. The Times, as you know, is the last liberal paper in America. In other words, if there was a war between North Korea and Iran and they both used nuclear weapons, this is the way the Times would report it: NUCLEAR WAR! WORLD ENDS! And below the fold: WOMEN AND MINORITIES HIT HARDEST.”

The show continues past midnight, Sahl drawing from an arsenal of material compiled over a span of sixty years and eleven presidencies. On stage he is uniquely alone; he has no writers, no peers in the narrow field of political satire. There is an easy authority in his voice, the kind that comes from the knowledge that all the public figures on whom he once cut his teeth have now passed from the scene. By sheer animal endurance he is the victor, the conquering hero, the last man standing in a field of giants. Toward the close of the evening he takes questions called to him from the audience and responds extemporaneously. In all, it would be a sterling performance for a man half his age.

It probably doesn’t occur to anyone—other than, perhaps, the man himself—that in its dimensions and intimacies, the Café Carlyle isn’t much different from the bohemian space in San Francisco where Mort Sahl began mixing hard news and comedy in 1953. North Beach, which extended from Chinatown to Fisherman’s Wharf, was the section of town where the pizza parlors and steakhouses kept late hours and the clubs offered everything in the way of entertainment from striptease to opera. It was noisy, colorful, aromatic, a place where all cultures and ethnicities could comfortably mix. Slashing through the center of it all was Columbus Avenue, home to Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Bookstore; the Black Cat bar, which singer Maya Angelou recalled as “a meeting place for very elegant homosexuals”; a cellar place near the intersection of Columbus and Jackson called the Purple Onion; and, directly across the street from the Onion, down a flight of marble stairs, the hungry i.

There were no banquettes in the basement of the shabby old Sentinel Building, a copper-clad flatiron dating from 1907, but there was a grand piano, the entertainment policy having been strictly musical up until Sahl’s debut. The room sat eighty-three on kitchen chairs and old school benches, but standing room could swell the capacity to a hundred or more on a good night. The cover charge, collected at the top of the steps, was twenty-five cents on weekdays, fifty on weekends.

The hungry i first opened its doors on September 9, 1950, as a membership club catering to artists and musicians. The founder was an enormous German-born impresario and sometime actor named Eric Nord, whose size brought him the sobriquet “Big Daddy.” The name of the place was properly expressed in lower case, but the press rarely complied. “I started to paint ‘hungry intellectual,’ across the door,” Nord would explain, “and ran out of space.” The walls were bare concrete and the bar, at which the featured drink was mulled wine, was all of six feet in length.

Open until three in the morning, the club was a hit with students and the free-thinking denizens of Telegraph Hill. Nord stuck with it a year and some months, but after drawing a fifteen-day penalty for serving liquor to a minor, he sold the hungry i to one of his patrons for $800. “It was relaxed and funky,” reasoned the buyer, a beret-wearing restaurateur named Enrico Banducci. A natural showman, Banducci formalized the entertainment calendar and made the hungry i something more than a mere hangout. A rug thrown on the concrete floor became the stage, its only dressing an apple crate on which the featured performer, a muscular folk singer named Stan Wilson, rested a foot while strumming his guitar. Lighting came from candles flickering atop a few low tables and the tips of countless cigarettes. “‘European’ was the adjective people always used to describe it,” said Donald Pippin, who played the piano there five nights a week. “In the warm glow, it was not hard to imagine oneself in Paris or the dream city of one’s choice.”

On the evening of December 22, 1953, a slight, diffident man took the stage in a brown suit salvaged from the traveling wardrobe of the Stan Kenton band. The newspaper he held in his hands wasn’t merely a prop; his cues, typed out on index cards, were stapled to its inside pages. There is no record of what he said, nor precisely how long he was on, but by all accounts he went over big. Don Steele, who was there in his capacity as entertainment columnist for the Oakland Tribune, recalled that “like all pure genius” Mort Sahl was as clever that first night as he would later be as an established headliner. If Steele sensed that Sahl had jammed the room with friends, UC students intent on laughing at practically anything the young comedian said, he never let on.

The job at the hungry i was the result of an awkward audition that had taken place a couple of weeks earlier. The pitch was made by Larry Tucker, a pal from Los Angeles who had appointed himself Mort’s manager for the occasion.* Witnessing the performance were Enrico, his manager Barry Drew, and Stan Wilson. The man Tucker placed before them was pallid and underfed, a five o’clock shadow suggesting he may have spent the night under a car. Banducci didn’t think much of his brief set with the exception of one joke. At a crowded press conference, President Eisenhower, who had always resisted taking a public stand against Joseph McCarthy, strongly endorsed Secretary of State John Foster Dulles’ characterization of the senator as “arrogant, blustering, and domineering.” Without mentioning McCarthy by name, the president added: “The easiest thing to do with great power is to abuse it—to use it in excess.”

Taking the cue, Sahl recalled his army days and the design of the famed Eisenhower field jacket, praising the flaps that prevented its button front and breast pockets from catching on equipment and describing its “multidirectional zippers” in elaborate detail. “You have zippers over here you can put your pencils in … and a zipper here you can open for your cigarettes and cigars.… And you had a big zipper here and you reached in and you pulled out all your maps …” He then suggested that the army, having been called a “communist bastion” by McCarthy, could redesign the Ike jacket to become a McCarthy jacket by adding a flap “which buttons over the mouth.” The senator, he observed, “doesn’t question what you say so much as your right to say it.”

Edward R. Murrow’s famous takedown of McCarthy on See It Now was still three months in the future. There had been no frontal assaults from the dominant TV comedians of the day—Groucho Marx, Milton Berle, Jackie Gleason—and Bob Hope’s infrequent cracks almost came across as friendly. Nightclub comics were even more circumspect than the media variety, always wary of turning a drinking crowd hostile. “The rest of Mort’s audition was terrible,” Banducci said, “but that joke killed me.”

Not quite knowing what to do with the guy, Banducci took him next door and staked him to a meal. “You look like you are starving,” he said, “and even if you never work, here’s twenty dollars.” When he learned that singer Dorothy Baker, the supporting act on the bill with Wilson, wanted to spend Christmas in Los Angeles with lyricist Jack Brooks, Banducci offered Sahl $75 to take the week. For a man just a few dollars short of vagrancy, it was a windfall. That first Tuesday night performance doubtless included the McCarthy joke, but Mort remembers another political jape that may actually have been his first: “Every time the Russians throw an American in jail,” went the observation, “we throw an American in jail to show them they can’t get away with it!”

In all, there wasn’t a lot of political content. “It was women and behavior and trying to get along in the system,” Mort says. “It was sort of random.” And without the help of his student claque, the rest of the week didn’t go as well. “It was horrible. That was when the hungry i sold only beer and wine, and the pre-liquor license stratum threw things—peanuts, water glasses, bottle caps.” The only other comic in town that week was the manic Pinky Lee, who was playing to packed houses at Bimbo’s 365 Club. “Enrico wanted to fire me,” said Mort, “but he was too kindhearted. At the end of the third week, I broke the sound barrier and I was in.”

Dorothy Baker, who eventually married Jack Brooks, never returned to the hungry i. Her permanent absence forced Enrico Banducci to do what he could to put Mort Sahl across. “I didn’t care for nightclubs,” Banducci said. “I detested those kinds of nightclubs where girls came out and danced and sang and a stupid comic would come out and say stupid jokes. I wanted a place where a lot of expression went on.” He liked the sophisticated stuff in Mort’s act; there just wasn’t enough of it. “It was new to hear him talk about political situations. That was new in entertainment. They weren’t even doing it in New York yet.”

With his dislike of traditional nightclub comedians, Banducci urged Sahl to look as nontraditional as his material. “Enrico said, ‘Take the tie off.’ Then he said, ‘Take the coat off.’ And then I said to myself: Who would ruminate on this? A graduate student. In those days the preppy thing was in. That’s where the sweater came from—the sweater and loafers. It was easier for them to process it from a guy that wasn’t dressed up.” The change of clothes was only the start; the new jokes had to be smarter, snappier. “I hid behind the material,” Mort admits. “I felt naked up there.” The audience, he found, wanted to be as smart as the man on stage. “They wanted to be on the level of the material—but not always. They can be very, very savage. In the beginning I just wanted them to laugh, but they were pretty resistant. Enrico would start the laughter over the P.A. system.” Banducci impressed him as an old-world character, a man who saw life through the eyes of an artist. “He seemed like a guy from another country—singing opera, playing the violin. He was the greatest chef. He was a guy with flair. He had the flamboyance to create things.”

Just as he was breaking through, Sahl had his first taste of public notice with an item in Herb Caen’s Examiner column: “Herbert Hoover and his fellow high-collarites will be shocked to learn that Mort Sahl, new comic at the Hungry I, is doing a Sahlacious routine called ‘Palo Alto, City of Sin.’ Must be a different Palo Alto.”

Caen had been writing about the city and its nightlife since 1938, and his column, as was frequently noted, was more widely read than the front page. The mention brought an immediate surge of interest in the unconventional comedian opening for Stan Wilson, a circumstance that didn’t sit well with the singer, a black postal employee from Oakland who mixed calypso with folk ballads and modestly billed himself as “one of America’s greatest contributions to music.” Wilson, says Mort, saw him as a threat: “He had the club all to himself. It was sold out every night. And he had the girls that liked him up there doing that Belafonte stuff. He let me know that he was the boss and he wanted to cut my time—but the audience was the constituency.”

As word spread and the lines along Columbus grew, Banducci added shows—as many as five a night. Stan Wilson had his following, but now Mort Sahl was building one of his own. “I used to walk across the street to a Chinese restaurant and write jokes in a book,” he says. “And I found out that’s not the way to do it. But I never made that public because the people I considered my enemy were actors that improvised. I thought it was anti-intellectual, so I didn’t want to do it. I was very much a puritan in that sense.” Not yet knowing his onstage character, he had not yet found his voice. That, he acknowledges, took a long time. “When I dropped the memorized act and threw in the asides—the observations—that won people, but I was too intimidated to do it.”

Commuting from Berkeley in a dilapidated Jaguar, Sahl occasionally had one of his pals from campus, an English major named John Whiting, along for the ride. “He never stopped talking,” Whiting recalled in an essay:

On the way he’d pick up the evening Examiner from a newspaper dispenser and leave it folded on the seat beside him. He didn’t look at it until he went on stage, whereupon he opened it up and took off from a headline like Charlie Parker chasing a fugitive melody. I’d sit through the evening’s shows wondering what he was going to say next—no two were ever the same. Then we’d pile into the Jag and head back across the bay to Kip’s, an all-night hamburger joint on Bancroft just below Telegraph. All the way back and into the morning, three A.M. or later, he never stopped talking. His monolog was as seamless and as endless as the Ring cycle, its familiar leitmotifs weaving in and out of the structure—Ike, Nixon, Joe McCarthy, the FBI, the D.A.R. All those uptight right-wingers who made the political, intellectual...