![]()

Part I. Necrophilologies

![]()

1. On the Nature of Marx’s Things

This potestas, this declinare is the defiance, the headstrongness of the atom, the quiddam in pectore of the atom; it does not characterize its relationship to the world as the relationship of the fragmented and mechanical world to the single individual.

As Zeus grew up to the tumultuous war dances of the Curetes, so here the world takes shape to the ringing war games of the atoms.

Lucretius is the genuine Roman epic poet, for he sings the substance of the Roman spirit.

(Diese potestas, dies declinare ist der Trotz, die Halsstarrigkeit des Atoms, das quiddam in pectore desselben, sie bezeichnet nicht ihr Verhältnis zur Welt, wie das Verhältnis der entzweigebrochnen, mechanischen Welt zum einzelnen Individuum.

Wie Zeus unter den tosenden Waffentänzen der Kureten aufwuchs, so hier die Welt unter dem klingenden Kampfspiel der Atome.

Lukrez ist der echt römischer Heldendichter, denn er besingt der Substanz des römischen Geistes.)

—Karl Marx, Notebooks on Epicurean Philosophy IV

“It goes without saying that but little use can be made of Lucretius” (Es versteht sich, dass Lucretius nur wenig benutzt werden kann). So, by way of preface or prophylaxis, opens the fourth of Karl Marx’s Notebooks on Epicurean Philosophy, composed around 1839 as Marx was preparing his doctoral dissertation. A long list of citations from De rerum natura follows, and then Lucretius is put to use—as Plutarch’s antagonist, in the long battle over the Epicurean tradition. In these early, informal notes by a young dissertator, the reception of Lucretius hangs in the balance; what Althusser refers to as an “underground current” of the materialism of the encounter surfaces and is soon, over the course of the next fifteen years, rechanneled or resubmerged. An account of mediation at odds with the mechanics, the economics, of use presents itself here, to be translated, never entirely successfully, first into the great Hegelian lexicon that the young Marx and his preceptors were unfolding, then into the languages of political economy. What sorts of use can be made of a thing? In what respect is Lucretius something to be used?

This is how Marx puts it:

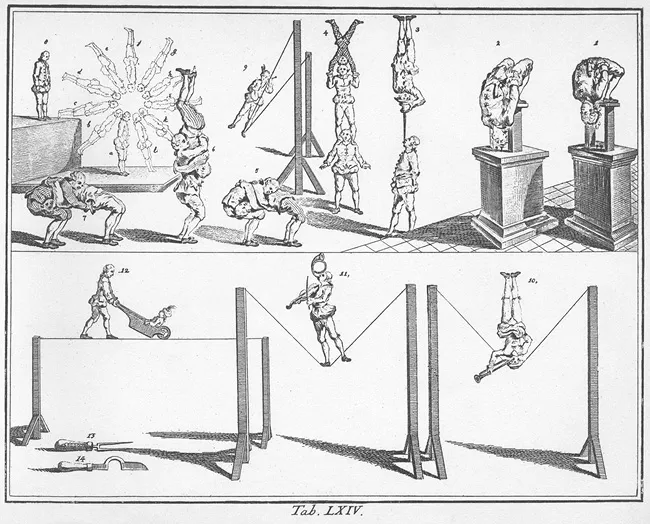

As nature in spring lays herself bare and, as though conscious of victory, displays all her charm, whereas in winter she covers up her shame and nakedness with snow and ice, so Lucretius, fresh, keen, poetic master of the world, differs from Plutarch, who covers his paltry ego [his “small ‘I’ ”: sein kleines Ich] with the snow and ice of morality. When we see an individual anxiously buttoned-up and clinging into himself, we involuntarily clutch at coat and clasp, make sure that we are still there, as if afraid to lose ourselves. But at the glimpse [Anblick] of an intrepid acrobat we forget ourselves, feel ourselves raised [erhaben] out of our own skins like universal forces [allgemeine Mächte] and breathe more fearlessly. Who is it that feels in the more moral [sittlich] and free state of mind—he who has just come out of Plutarch’s classroom, reflecting on how unjust it is that the good should lose with life the fruit of their life, or he who sees eternity fulfilled, hears the bold thundering song of Lucretius?

These are marvelous lines—rich and complex, evocative, precise. Marx’s enthusiasm for Lucretius’s “bold,” “acrobatic” verse, for the “infinitely more philosophical” interpretation of Epicurus he offers than we find in the wintry Plutarch—this shines through. We admire the “poetic master of the world”; we “forget ourselves”; at the glimpse of Lucretius’s verse what was “small” about our “I” is forgotten and expands to fill the vertiginous air below the acrobat. Lucretius’s verse dances dangerously above the world of things, Marx says: here, at this circle, standing as it were by the seaside, Marx describes not (as Lucretius does in the poem) a vessel’s catastrophe but a world of things and states of affairs, and a world above it, a world of poetic turns and propositions made philosophically as well as poetically, concerning and corresponding to that world of states of affairs and things. How will Marx make use of Lucretius, use of a discursive realm whose figures turn in paths parallel to the wintry tracks of things below, enskied things above in correspondence with those below, some force drawing them together, the poet’s art pulling them apart; gravity (or whatever norm “gravity” stands for here: let’s call it “reference,” or “correspondence,” or “continuity,” or the rule of “parallelism,” always bearing in mind that each of these terms works in its own lexical-philosophical frame, as well as in relation to the other terms here), “gravity” threatening always to plunge the acrobat, or the poet, or the Lucretian philosopher, from the air in which he or she spins toward things below?

One answer to this question is obvious enough. On reading Lucretius, Marx seems licensed by the vigor and intelligence of the poet’s verse to spread his own literary wings and to treat himself to climatological antitheses, mythologies, analogies, anthropomorphisms, and epic similes: “As nature in spring lays herself bare,” he writes, “and, as though conscious of victory, displays all her charm, whereas in winter she covers up her shame and nakedness with snow and ice, so Lucretius, fresh, keen, poetic master of the world, differs from Plutarch.” Marx trots out a small stable of poetical and rhetorical tricks that echo the invocation of Venus at the opening of De rerum natura, where the Aeneadum genetrix is said to be acclaimed by nature “simul ac species patefactast verna diei” (as soon as the vernal face of day is made manifest). But these lines express also a degree of anxiety. The acrobatic thrill of flying with Lucretius, of catching a glimpse of nature’s ravishing and seductive nakedness, of forgetting ourselves—all these mark the philosophically familiar experience of feeling upraised, erhaben, sublimated. For this early Marx, to read Lucretius is to come across that which elevates-exposes us and threatens us with a loss of self that is correlative to the expansion of our “small I” into the space between the acrobat and the ground, between the world of poetic figures and the wintry ground of things. We may feel “like” universal forces when we come across Lucretius’s verse, but only when we have forgotten that we are not; spring’s victory always slips into winter’s grasp, and back out again. We purchase a certain sort of moral disposition—Sittlichkeit—and a feeling of increased freedom on the coin of this sublime and sublimating exposure, and on the back of a necessary forgetting that is brought about by Lucretius’s boldness. Just what sort of moral disposition this is, and just what sort of freedom is contingent upon sublime forgetting, and what, beyond our “small I” and “paltry egos,” we must forget in order to achieve a free moral disposition—these questions are themselves momentarily forgotten, in the thrill of Lucretius’s victory over Plutarch.

But only momentarily, and never entirely. Manifestly, Marx approaches De rerum natura in the epic-poetic mode that Lucretius’s verse puts at his disposal, but also through or against the elevating, sublimating lexicon of Kantian aesthetics—among others. At this level, “forgetting” does not obtain. Marx’s readers—and, as these lines are private notes, intended for Marx’s own use alone, the only “reader” of interest here is Marx himself—Marx’s readers, Marx himself, are invited to recall the artifice of Lucretius’s verse and the long tradition, epic as well as philosophical, that it engages. At “the glimpse [Anblick] of an intrepid acrobat,” then, we may well “forget ourselves,” but at the glimpse of Marx’s summary account of the experience of reading Lucretius we recall that when we then, and consequently, “feel ourselves raised [erhaben] out of our own skins like universal forces [allgemeine Mächte] and breathe more fearlessly,” we are rejoining an aesthetic tradition, and a tradition of writing about aesthetics, that places us in our own skin again, wraps us back into a philosophical surface on which the lexicon of our experience is detailed. Here, in short, the determining laws of mediation draw Marx the reader toward Marx the writer of these notebooks, just as the epic simile with which Marx opens this notebook draws him into analogy with the epic poem of nature itself, draws Marx into contact with Lucretius. Here, then, the philosopher’s “small I” coincides with itself, as the writer of these notebooks coincides with their reader, when it glimpses itself in the shape of the Roman poet, in the skin of the Kantian aesthetician, who people the element in which the dance of poetical figures and of philosophical propositions corresponds, mediately, to the world of things and states of affairs.

If this sounds rather imprecise, it is because Marx is treading on very tricky ground indeed. Marx is careful to leave the “glimpse” that Lucretius affords him at just that—a glimpse. The domain of the acrobat (Luftspringer is the wonderful word Marx uses: the air-jumper) remains the pastoral world of the circus, set aside from the humdrum, workaday world in the same way that the sublime experience serves more as an interruption, an epochal punctuation, than a part of the fabric of our “paltry” lives. Spring, the appearance of Venus, the reading of Lucretius’s poem, these are radically heterogenous with respect to the wintry, encloaked body of the paltry I, the world where the mere “usefulness” of one or another experience is the measure of its worth—for example, the “experience” of reading Lucretius. And vice versa; my glimpse of the acrobat is nothing at all like the way I see the shivering, Plutarchan moralist, the acrobat, as different from Plutarch as spring’s female charms are from winter’s harsh grasp. But the circus and the sublime landscape are also inextricably connected with the world from which they escape. Even Marx’s strange analogies tell us as much: nature remains the same—same in name, same in continuous substance—beneath the exposure of her springtime victory or the huddled mantle of winter; I may forget myself on glimpsing the acrobat, but I gaze at him with the same eye that has seen the shivering Plutarch. Lucretius’s verse is at one and the same time “of little use” in understanding the difference between the Democritean and Epicurean systems, and is indispensable, inasmuch as it provides the point at which I, Marx-the-writer and I, Marx-the-reader, coincide, where the forgetting that Marx-the-writer demands shows itself to be correlative to the remembering that Marx-the-reader exemplifies. Winter and spring, the flight of the acrobat and the pedestrian tread of the schoolteacher: these are accidents of nature or of the “small I” or the “paltry ego,” mere eventa, circumstantial and disseverable properties; and they are also coniuncta, nonseverable and constitutive properties “which without destructive dissolution can never be separate or disjoined” from substances, “id quod nusquam sine permitiali discidio potis,” in the words of the poem (book 1, l. 451). The world of things and the world of statements about things remain correspondent, parallel, symmetrical; and they lean in, collapse, fall, decline into one another.

One imagines as a result two destinies, two uses, for Lucretius, encoded in these letters that the young Marx sends to himself, in these notebooks in which he sketches for himself the outlines of the Epicurean tradition. These uses, these destinies for Lucretius set the pattern to which Marx will make other forms of thought conform. On the one hand, we imagine a line of thinking stressing the sublime, indeed unbreachable, difference between the world of things and the lofty, Luftig world of statements about things. The acrobatic figures of De rerum natura are, on this description, the epitome of what Marx will call, in the first of the “Theses on Feuerbach,” “all hitherto existing materialism,” inasmuch as in this circus world “the thing, reality, sensuousness, is conceived only in the form of the object or of contemplation, but not as sensuous human activity, practice, not subjectively.” In the “Theses,” such Feuerbachian, excessively strong materialism leads to the idealization of “things” rather than to their being understood as the result of, or under the aspect of, practice. “Things” imagined as ob-jects, objects-for-consciousness or for thought, and in a specular and parallel determination, thought imagined as the contemplation of objects-for-thought alone; an adequation of thought to object-for-thought and vice versa; the pure, unthought immediacy of thought to itself. On the other hand, one imagines the collapse of the plane of figures onto that of “things.” On this side, we find a materialism of a different sort—even of a different national lineage, an antimetaphysical, British materialism, a materialism of cases for which no figure is to be found. This Marx describes elsewhere, also quite famously, as Baconian, based in the senses, experimental, nominalist. Things, on this side, imagined as for-themselves alone; the work of thought, producing hypotheses about things alone to be tested in the event; thought, an activity of a consciousness alone among things, a thing among other things; relation, which might be construed as an abstract figure corresponding to the plane of things in themselves, demoted, fallen to earth, a further thing among things; the pure, unthought immediacy of the thing to itself.

These two declensions of Marx’s early encounter with Lucretius appear to mark the outside limits of Marx’s thought on materialism, and in particular on the status of things in and for thought. (Are mental objects material? In what sense?) But already at this stage of Marx’s career this description is inadequate—inadequate to Marx’s understanding of things, inadequate to his reading of Lucretius.

Let me now turn to a third, decisive aspect to Marx’s earliest encounters with Lucretius. Marx gives a fairly stra...