![]()

PART I

Roads to Sarajevo

![]()

1

Serbian Ghosts

MURDER IN BELGRADE

Shortly after two o’clock on the morning of 11 June 1903, twenty-eight officers of the Serbian army approached the main entrance of the royal palace in Belgrade. After an exchange of fire, the sentries standing guard before the building were arrested and disarmed. With keys taken from the duty captain, the conspirators broke into the reception hall and made for the royal bedchamber, hurrying up stairways and along corridors. Finding the king’s apartments barred by a pair of heavy oaken doors, the conspirators blew them open with a carton of dynamite. The charge was so strong that the doors were torn from their hinges and thrown across the antechamber inside, killing the royal adjutant behind them. The blast also fused the palace electrics, so that the building was plunged into darkness. Unperturbed, the intruders discovered some candles in a nearby room and entered the royal apartment. By the time they reached the bedroom, King Alexandar and Queen Draga were no longer to be found. But the queen’s French novel was splayed face-down on the bedside table. Someone touched the sheets and felt that the bed was still warm – it seemed they had only recently left. Having searched the bedchamber in vain, the intruders combed through the palace with candles and drawn revolvers.

While the officers strode from room to room, firing at cabinets, tapestries, sofas and other potential hiding places, King Alexandar and Queen Draga huddled upstairs in a tiny annexe adjoining the bedchamber where the queen’s maids usually ironed and darned her clothes. For nearly two hours, the search continued. The king took advantage of this interlude to dress as quietly as he could in a pair of trousers and a red silk shirt; he had no wish to be found naked by his enemies. The queen managed to cover herself in a petticoat, white silk stays and a single yellow stocking.

Across Belgrade, other victims were found and killed: the queen’s two brothers, widely suspected of harbouring designs on the Serbian throne, were induced to leave their sister’s home in Belgrade and ‘taken to a guard-house close to the Palace, where they were insulted and barbarously stabbed’.1 Assassins also broke into the apartments of the prime minister, Dimitrije Cincar-Marković, and the minister of war, Milovan Pavlović. Both were slain; twenty-five rounds were fired into Pavlović, who had concealed himself in a wooden chest. Interior Minister Belimir Theodorović was shot and mistakenly left for dead but later recovered from his wounds; other ministers were placed under arrest.

Back at the palace, the king’s loyal first adjutant, Lazar Petrović, who had been disarmed and seized after an exchange of fire, was led through the darkened halls by the assassins and forced to call out to the king from every door. Returning to the royal chamber for a second search, the conspirators at last found a concealed entry behind the drapery. When one of the assailants proposed to cut the wall open with an axe, Petrović saw that the game was up and agreed to ask the king to come out. From behind the panelling, the king enquired who was calling, to which his adjutant responded: ‘I am, your Laza, open the door to your officers!’ The king replied: ‘Can I trust the oath of my officers?’ The conspirators replied in the affirmative. According to one account, the king, flabby, bespectacled and incongruously dressed in his red silk shirt, emerged with his arms around the queen. The couple were cut down in a hail of shots at point-blank range. Petrović, who drew a concealed revolver in a final hopeless bid to protect his master (or so it was later claimed), was also killed. An orgy of gratuitous violence followed. The corpses were stabbed with swords, torn with a bayonet, partially disembowelled and hacked with an axe until they were mutilated beyond recognition, according to the later testimony of the king’s traumatized Italian barber, who was ordered to collect the bodies and dress them for burial. The body of the queen was hoisted to the railing of the bedroom window and tossed, virtually naked and slimy with gore, into the gardens. It was reported that as the assassins attempted to do the same with Alexandar, one of his hands closed momentarily around the railing. An officer hacked through the fist with a sabre and the body fell, with a sprinkle of severed digits, to the earth. By the time the assassins had gathered in the gardens to have a smoke and inspect the results of their handiwork, it had begun to rain.2

The events of 11 June 1903 marked a new departure in Serbian political history. The Obrenović dynasty that had ruled Serbia throughout most of the country’s brief life as a modern independent state was no more. Within hours of the assassination, the conspirators announced the termination of the Obrenović line and the succession to the throne of Petar Karadjordjević, currently living in Swiss exile.

Why was there such a brutal reckoning with the Obrenović dynasty? Monarchy had never established a stable institutional existence in Serbia. The root of the problem lay partly in the coexistence of rival dynastic families. Two great clans, the Obrenović and the Karadjordjević, had distinguished themselves in the struggle to liberate Serbia from Ottoman control. The swarthy former cattleherd ‘Black George’ (Serbian: ‘Kara Djordje’) Petrović, founder of the Karadjordjević line, led an uprising in 1804 that succeeded for some years in driving the Ottomans out of Serbia, but fled into Austrian exile in 1813 when the Ottomans mounted a counter-offensive. Two years later, a second uprising unfolded under the leadership of Miloš Obrenović, a supple political operator who succeeded in negotiating the recognition of a Serbian Principality with the Ottoman authorities. When Karadjordjević returned to Serbia from exile, he was assassinated on the orders of Obrenović and with the connivance of the Ottomans. Having dispatched his main political rival, Obrenović was granted the title of Prince of Serbia. Members of the Obrenović clan ruled Serbia during most of its existence as a principality within the Ottoman Empire (1817–78).

Petar I Karadjordjević

The pairing of rival dynasties, an exposed location between the Ottoman and the Austrian empires and a markedly undeferential political culture dominated by peasant smallholders: these factors in combination ensured that monarchy remained an embattled institution. It is striking how few of the nineteenth-century Serbian regents died on the throne of natural causes. The principality’s founder, Prince Miloš Obrenović, was a brutal autocrat whose reign was scarred by frequent rebellions. In the summer of 1839, Miloš abdicated in favour of his eldest son, Milan, who was so ill with the measles that he was still unaware of his elevation when he died thirteen days later. The reign of the younger son, Mihailo, came to a premature halt when he was deposed by a rebellion in 1842, making way for the installation of a Karadjordjević – none other than Alexandar, the son of ‘Black George’. But in 1858, Alexandar, too, was forced to abdicate, to be succeeded again by Mihailo, who returned to the throne in 1860. Mihailo was no more popular during his second reign than he had been during the first; eight years later he was assassinated, together with a female cousin, in a plot that may have been supported by the Karadjordjević clan.

The long reign of Mihailo’s successor, Prince Milan Obrenović (1868–89), provided a degree of political continuity. In 1882, four years after the Congress of Berlin had accorded Serbia the status of an independent state, Milan proclaimed it a kingdom and himself king. But high levels of political turbulence remained a problem. In 1883, the government’s efforts to decommission the firearms of peasant militias in north-eastern Serbia triggered a major provincial uprising, the Timok rebellion. Milan responded with brutal reprisals against the rebels and a witch-hunt against senior political figures in Belgrade suspected of having fomented the unrest.

Serbian political culture was transformed in the early 1880s by the emergence of political parties of the modern type with newspapers, caucuses, manifestos, campaign strategies and local committees. To this formidable new force in public life the king responded with autocratic measures. When elections in 1883 produced a hostile majority in the Serbian parliament (known as the Skupština), the king refused to appoint a government recruited from the dominant Radical Party, choosing instead to assemble a cabinet of bureaucrats. The Skupština was opened by decree and then closed again by decree ten minutes later. A disastrous war against Bulgaria in 1885 – the result of royal executive decisions made without any consultation either with ministers or with parliament – and an acrimonious and scandalous divorce from his wife, Queen Nathalie, further undermined the monarch’s standing. When Milan abdicated in 1889 (in the hope, among other things, of marrying the pretty young wife of his personal secretary), his departure seemed long overdue.

The regency put in place to manage Serbian affairs during the minority of Milan’s son, Crown Prince Alexandar, lasted four years. In 1893, at the age of only sixteen, Alexandar overthrew the regency in a bizarre coup d’état: the cabinet ministers were invited to dinner and cordially informed in the course of a toast that they were all under arrest; the young king announced that he intended to arrogate to himself ‘full royal power’; key ministerial buildings and the telegraph administration had already been occupied by the military.3 The citizens of Belgrade awoke on the following morning to find the city plastered with posters announcing that Alexandar had seized power.

In reality, ex-King Milan was still managing events from behind the scenes. It was Milan who had set up the regency and it was Milan who engineered the coup on behalf of his son. In a grotesque family manoeuvre for which it is hard to find any contemporary European parallel, the abdicated father served as chief adviser to the royal son. During the years 1897–1900, this arrangement was formalized in the ‘Milan–Alexander duarchy’. ‘King Father Milan’ was appointed supreme commander of the Serbian army, the first civilian ever to hold this office.

During Alexandar’s reign, the history of the Obrenović dynasty entered its terminal phase. Supported from the sidelines by his father, Alexandar quickly squandered the hopeful goodwill that often attends the inauguration of a new regime. He ignored the relatively liberal provisions of the Serbian constitution, imposing instead a form of neo-absolutist rule: secret ballots were eliminated, press freedoms were rescinded, newspapers were closed down. When the leadership of the Radical Party protested, they found themselves excluded from the exercise of power. Alexandar abolished, imposed and suspended constitutions in the manner of a tinpot dictator. He showed no respect for the independence of the judiciary, and even plotted against the lives of senior politicians. The spectacle of the king and King Father Milan recklessly operating the levers of the state in tandem – not to mention Queen Mother Nathalie, who remained an important figure behind the scenes, despite the breakdown of her marriage with Milan – had a devastating impact on the standing of the dynasty.

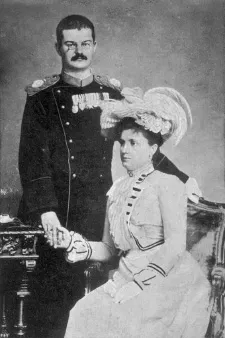

Alexandar’s decision to marry the disreputable widow of an obscure engineer did nothing to improve the situation. He had met Draga Mašin in 1897, when she was serving as a maid of honour to his mother. Draga was ten years older than the king, unpopular with Belgrade society, widely believed to be infertile and well known for her allegedly numerous sexual liaisons. During a heated meeting of the Crown Council, when ministers attempted in vain to dissuade the king from marrying Mašin, the interior minister Djordje Genčić came up with a powerful argument: ‘Sire, you cannot marry her. She has been everybody’s mistress – mine included.’ The minister’s reward for his candour was a hard slap across the face – Genčić would later join the ranks of the regicide conspiracy.4 There were similar encounters with other senior officials.5 At one rather overwrought cabinet meeting, the acting prime minister even proposed placing the king under palace arrest or having him bundled out of the country by force in order to prevent the union from being solemnized.6 So intense was the opposition to Mašin among the political classes that the king found it impossible for a time to recruit suitable candidates into senior posts; the news of Alexandar and Draga’s engagement alone was enough to trigger the resignation of the entire cabinet and the king was obliged to make do with an eclectic ‘wedding cabinet’ of little-known figures.

The controversy over the marriage also strained the relationship between the king and his father. Milan was so outraged at the prospect of Draga’s becoming his daughter-in-law that he resigned his post as commander-in-chief of the army. In a letter written to his son in June 1900, he declared that Alexandar was ‘pushing Serbia into an abyss’ and closed with a forthright warning: ‘I shall be the first to cheer the government which shall drive you from the country, after such a folly on your part.’7 Alexandar went ahead just the same with his plan (he and Draga were married on 23 June 1900 in Belgrade) and exploited the opportunity created by his father’s resignation to reinforce his own control over the officer corps. There was a purge of Milan’s friends (and Draga’s enemies) from senior military and civil service posts; the King Father was kept under constant surveillance, then encouraged to leave Serbia and later prevented from returning. It was something of a relief to the royal couple when Milan, who had settled in Austria, died in January 1901.

There was a brief revival in the monarch’s popularity late in 1900, when an announcement by the palace that the queen was expecting a child prompted a wave of public sympathy. But the outrage was correspondingly intense in April 1901 when it was revealed that Draga’s pregnancy had been a ruse designed to placate public opinion (rumours spread in the capital of a foiled plan to establish a ‘suppositious infant’ as heir to the Serbian throne). Ignoring these ill omens, Alexandar launched a propaganda cult around his queen, celebrating her birthday with lavish public events and naming regiments, schools and even villages after her. At the same time, his constitutional manipulations became bolder. On one famous occasion in March 1903, the king suspended the Serbian constitution in the middle of the night while repressive new press and association laws were hurried on to the statute books, and then reinstated it just forty-five minutes later.

King Alexandar and Queen Draga c. 1900

By the spring of 1903, Alexandar and Draga had united most of Serbian society against them. The Radical Party, which had won an absolute majority of Skupština seats in the elections of July 1901, resented the king’s autocratic manipulations. Among the powerful mercantile and banking families (especially those involved in the export of livestock and foodstuffs) there were many who saw the pro-Vienna bias of Obrenović foreign policy as locking the Serbian economy into an Austrian monopoly and depriving the country’s capitalists of access to world markets.8 On 6 April 1903, a demonstration in Belgrade decrying the king’s constitutional manipulations was brutally dispersed by police and gendarmes, who killed eigh...