1

The Motive Spectrum

| The Six Reasons We Work

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has a serious problem: too many of its citizens are overweight or obese.1 In the summer of 2013, the government of Dubai took action, launching a weight-loss challenge it called “Your Weight in Gold.”

Dubai followed a playbook that many companies have used to change people’s behavior: it offered a reward. For every kilogram of weight that residents lost between July and mid-August, it would pay them one gram of gold.2 That seems like a reasonable strategy—after all, people will do a lot more than diet in the pursuit of gold. And sure enough, when the contest ended, about 25 percent of the 10,6663 people who entered4 the challenge had lost enough weight to claim a prize. Big success, right?

Not exactly. Scientists have studied what happens when people are paid to lose weight, and the results are not very encouraging. Consider an experiment conducted by four university researchers.5 Coincidentally, its design is very similar to “Your Weight in Gold.”

During a three-week program, test subjects were paid about $50 per week (roughly the value of a gram of gold6) to lose weight. After the program ended, their weight was tracked for another four months. But before it all began, the test subjects’ motives for joining the program were assessed. Why were they there?

Imagine two hypothetical test subjects, Jake and Christine. Jake sees the flyer for the experiment and decides to sign up because he needs the money. The money is his motive. Christine sees the same flyer and decides it would be a great opportunity to lose weight. For her, the money is not the main factor. She’s there for the learning, the coaching, and the community.

Jake and the other test subjects like him formed the financially motivated group. Christine and the other subjects like her formed the nonfinancially motivated group. As you’d expect, Jake and the financially motivated group lost weight—0.25 percent of their weight on average. It looked like the financial reward had somewhat successfully motivated behavior. Mission accomplished!

Not so fast. . . .

After they’d collected their rewards, Jake and his group went on to gain weight. Over the next four months, Jake and his group gained back the weight they had lost and added more on top of that. The reward might have instigated behavior, but it didn’t build persistence.

Meanwhile, Christine and her group saw better results. On average they lost about 1.5 percent of their weight (six times what Jake and his group lost) during the program. Over the next four months, they kept the weight off and lost even more (another half a percent).

The experiment has a simple yet profound lesson: why people participate in an activity affects their performance in that activity. Their motive affects their performance.

Even though many organizations rely on money to drive performance, most of us know from our personal lives that motivation is much more complicated. There is a spectrum of reasons why people do their jobs (or lose weight). Understanding that spectrum is the key to creating the highest levels of performance.

THE MOTIVE SPECTRUM

Before we can explain a phenomenon scientifically, it is easy to mistake it for magic.

When we speak with leaders about culture building, they often tell us that it takes special powers of the kind that only a Steve Jobs (Apple), Herb Kelleher (Southwest Airlines), Phil Jackson (legendary coach of the Chicago Bulls and LA Lakers), or some other wizard is graced with. What hope do mere mortals have?

A good first step to turning magic into science is the creation of a framework that helps make predictions. Ideally, this framework organizes all of your scientific observations in a way that helps you see new patterns. This is what happened with alchemy.

Alchemists believed that all matter was composed of earth, air, fire, and water. For centuries they mixed and remixed materials in an attempt to produce the mythical philosopher’s stone, which they believed had the power to transform base metals, like iron, into gold, and to confer immortality. Instead, they discovered chemistry.

Chemistry took its biggest leap forward in 1869 when the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev produced the Periodic Table of Elements. “I saw in a dream a table where all elements fell into place as required,” he said later. “Awakening, I immediately wrote it down on a piece of paper.”7 Thanks to this organizing framework, Mendeleev was able to predict the properties of elements that had not yet been discovered.8 What had once been magic was now firmly in the realm of science.

In our own day, an analogous discovery has sparked a great flowering of the science of human performance. In the mid-1980s, Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan of the University of Rochester published an audacious framework of human motives, a single spectrum cataloging the reasons that people engage in activities. They called it “self-determination theory.”9 Their seminal book Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior has been cited over twenty-two thousand times in other research. Compare that to the average number of citations a paper gets after ten years, just twenty.10 We’ve been deeply influenced by Deci and Ryan in our own research and practice. (A deeper explanation of how we have built on their and other researchers’ work can be found in the Appendix: “The Scientist’s Toothbrush”).

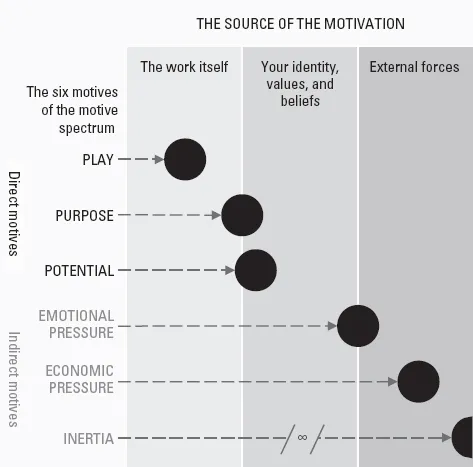

Figure 3: The motive spectrum in its entirety. The circles symbolically represent a person’s motive. For example, the purpose motive is mostly driven by the work itself, and partly by your own beliefs.

It turns out that there is a spectrum of reasons, or motives, for why people perform an activity. The first three, which we call the direct motives, are directly linked to the activity (in our case, work) and drive performance. The next three, the indirect motives, are further removed from the work itself and frequently harm performance.

Let’s go through the motives one by one, starting with play.

THE DIRECT MOTIVES

Play

You’re most likely to lose weight—or succeed in any other endeavor—when your motive is play. Play occurs when you’re engaging in an activity simply because you enjoy doing it. The work itself is its own reward. Scientists describe this motive as “intrinsic.”

Play is what compels you to take up hobbies, from solving crossword puzzles to making scrapbooks to mixing music. You may find play in weight loss by experimenting with healthy recipes or seeking out new restaurants that offer healthy options. Many of us are lucky enough to find play in the workplace too, when we do what we do simply because we enjoy doing it.

Curiosity and experimentation are at the heart of play. People intrinsically enjoy learning and adapting. We instinctively seek out opportunities to play.

Some companies actively encourage their employees to play in their work. Toyota gives factory workers the opportunity to come up with and test new tools and ideas on the assembly line. W. L. Gore & Associates, Google, and a number of other companies encourage play by giving people free time or resources to explore their own ideas. Zappos and Southwest Airlines encourage their people to treat each customer interaction as play. In each case, the organization encourages its people to indulge their curiosity—to play in the work itself.

Play at work should not be confused with your people playing Ping-Pong or foosball in the break room. For your people to feel play at work, the motive must be fueled by the work itself, not the distraction. Because the play motive is created by the work itself, play is the most direct and most powerful driver of high performance.

Purpose

A step away from the work itself is the purpose motive.11 The purpose motive occurs when you do an activity because you value the outcome of the activity (versus the activity itself). You may or may not enjoy the work you do, but you value its impact. You may work as a nurse, for example, because you want to heal patients. You spend your career studying culture because you believe in the impact your work can have on others. Dieters may not enjoy preparing or eating healthy meals, but they deeply value their own health, an outcome of healthy eating.

You feel the purpose motive in the workplace when your values and beliefs align with the impact of the work. Apple creates products that inspire and empower its customers, a purpose that is compelling and credible. The medical devices that Medtronic makes save lives; when its engineers and technicians see their products in action, it has a powerful effect on them.12 Walmart’s financial services division fueled purpose by kicking off its management meetings with a review of how much money the division had saved its customers rather than how much money Walmart had made for itself.13 As you’ll see in the coming chapters, a thoughtful organization can create authentic purpose for just about any type of work. Yet one of the biggest mistakes a company can make is trumpeting a grandiose purpose that isn’t authentic. If a purpose doesn’t feel credible, it won’t improve your motivation.

The purpose motive is one step removed from the work, because the motive isn’t the work itself but its outcome. While the purpose motive is a powerful driver of performance, the fact that it’s a step removed from the work typically makes it a less powerful motive than play.

Potential

The third motive is potential. The potential motive occurs when you find a second order outcome (versus a direct outcome) of the work that aligns with your values or beliefs. You do the work because it will eventually lead to something you believe is important, such as your personal goals.

For example, you may work as a paralegal because it will help you get into law school. You may not enjoy the day-to-day work of filing briefs (no play motive), and you may not care about helping the kinds of clients your firm represents (no purpose motive), but you continue to do the job because you want to be a public defender one day. You are working to bring about a second order outcome that you do believe in.

Dieters motivated by potential eat healthfully to achieve other things they care about—the ability to run faster on the football field, for example, or to keep up with their kids.

When a company describes a job as a good “stepping-stone,” they’re attempting to instill the potential motive. Some companies go out of their way to enhance the potential motive, offering classes that build skills or knowledge. General Electric draws talent through its reputation as “the leadership factory” for future CEOs.14

The potential motive is not as powerful as play or purpose, since it relates to a second order outcome of the work, which is two (or more) steps removed from the work itself.

We call play, purpose, and potential the “direct” motives because they’re the most directly connected to the work itself. As a result, they typically result in the highest levels of performance. If you remember only one thing from Primed to Perform, it should be that a culture that inspires people to do their jobs for play, purpose, and potential creates the highest and most sustainable performance.

You would think that the more reasons you give someone to work, the more dedicated they would be. But not all motives lead to higher levels of performance. Moving further along the motive spectrum, we re...