- 608 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

LiteraturaSubtopic

Literatura generalEIGHT

TERRORS

In search of a good scare, most people look to the cinema rather than to books, and for a very simple reason: films are more effective than ever at the business of making audiences jump. What they very often lack, of course, is an underbelly. They’re all surface. And in a genre which gains much of its power from the meanings which lurk behind the scenes, that can be a fatal absence.

That said, it’s undeniably fun simply to scare the fuck out of folks now and again. I’ve directed a few ghost-train rides of my own, and had a thoroughly good time doing it. In fact, two plays that are excerpted in this chapter—Frankenstein in Love and The History of the Devil—had more than a touch of the horror movie spirit in them when they were produced, and without having cut my teeth on their Grand Guignol excesses, I doubt I would have been confident enough to pursue the writing and directing of Hellraiser. A passage from the novella upon which that film is based also appears here, recording the first entrance of the demonic Cenobite who would eventually be dubbed “Pinhead.” In fact, the image of a human head spiked with nails is a common symbol, the Jungians say, of rage. There is a tradition of African fetish heads that use that image. I’m sure I’d seen such heads in books, and they were the inspiration for Pinhead.

Also in this chapter, “In the Hills, the Cities,” a short story which proved controversial before it was even published. My agent counseled against its publication; my editor at the time did the same. It was too surreal, and too blatantly homosexual. Fifteen years later, it still elicits responses from readers in practically every batch of mail. One of its inspirations is Goya’s Colossus, which depicts a giant striding away from a valley packed with tiny panicking figures. Another is the eighteenth century’s taste for rendering faces made from human figures (Archimboldo painted them, brilliantly, constructed from fish and vegetables). The third and final source is democracy itself: the notion that in exercising our democratic rights we make, as it were, a single will of our many wills.

Or so the idealists would have us believe. Since this story was written, the Soviet Union has dissolved, and what was once Yugoslavia has splintered into a number of warring factions. The atrocities from that region continue to make headlines. I claim no prophetic skills; but I think the story’s portrait of collective insanity appears horribly accurate.

From The Hellhound Heart

So intent was Frank upon solving the puzzle of Lemarchand’s box that be didn’t hear the great bell begin to ring. The device had been constructed by a master craftsman, and the riddle was this—that though he’d been told the box contained wonders, there simply seemed to be no way into it, no clue on any of its six black lacquered faces as to the whereabouts of the pressure points that would disengage one piece of this three-dimensional jigsaw from another.

Frank had seen similar puzzles—mostly in Hong Kong, products of the Chinese taste for making metaphysics of hard wood—but to the acuity and technical genius of the Chinese the Frenchman had brought a perverse logic that was entirely his own. If there was a system to the puzzle, Frank had failed to find it. Only after several hours of trial and error did a chance juxtaposition of thumbs, middle, and last fingers bear fruit: an almost imperceptible click, and then—victory!—a segment of the box slid out from beside its neighbors.

There were two revelations.

The first, that the interior surfaces were brilliantly polished. Frank’s reflection—distorted, fragmented—skated across the lacquer. The second, that Lemarchand, who had been in his time a maker of singing birds, had constructed the box so that opening it tripped a musical mechanism, which began to tinkle a short rondo of sublime banality.

Encouraged by his success, Frank proceeded to work on the box feverishly, quickly finding fresh alignments of fluted slot and oiled peg which in their turn revealed further intricacies. And with each solution—each new half twist or pull—a further melodic element was brought into play—the tune counterpointed and developed until the initial caprice was all but lost in ornamentation.

At some point in his labors, the bell had begun to ring—a steady somber tolling. He had not heard, at least not consciously. But when the puzzle was almost finished—the mirrored innards of the box unknotted—he became aware that his stomach churned so violently at the sound of the bell it might have been ringing half a lifetime.

He looked up from his work. For a few moments he supposed the noise to be coming from somewhere in the street outside—but he rapidly dismissed that notion. It had been almost midnight before he’d begun to work at the bird maker’s box; several hours had gone by—hours he would not have remembered passing but for the evidence of his watch—since then. There was no church in the city—however desperate for adherents—that would ring a summoning bell at such an hour.

No. The sound was coming from somewhere much more distant, through the very door (as yet invisible) that Lemarchand’s miraculous box had been constructed to open. Everything that Kircher, who had sold him the box, had promised of it was true! He was on the threshold of a new world, a province infinitely far from the room in which he sat.

Infinitely far; yet now, suddenly near.

The thought had made his breath quick. He had anticipated this moment so keenly, planned with every wit he possessed this rending of the veil. In moments they would be here—the ones Kircher had called the Cenobites, theologians of the Order of the Gash. Summoned from their experiments in the higher reaches of pleasure, to bring their ageless heads into a world of rain and failure.

He had worked ceaselessly in the preceding week to prepare the room for them. The bare boards had been meticulously scrubbed and strewn with petals. Upon the west wall he had set up a kind of altar to them, decorated with the kind of placatory offerings Kircher had assured him would nurture their good offices: bones, bonbons, needles. A jug of his urine—the product of seven days’ collection—stood on the left of the altar, should they require some spontaneous gesture of self-defilement. On the right, a plate of doves’ heads, which Kircher had also advised him to have on hand.

He had left no part of the invocation ritual unobserved. No cardinal, eager for the fisherman’s shoes, could have been more diligent.

But now, as the sound of the bell became louder, drowning out the music box, he was afraid.

Too late, he murmured to himself, hoping to quell his rising fear. Lemarchand’s device was undone; the final trick had been turned. There was no time left for prevarication or regret. Besides, hadn’t he risked both life and sanity to make this unveiling possible? The doorway was even now opening to pleasures no more than a handful of humans had ever known existed, much less tasted—pleasures which would redefine the parameters of sensation, which would release him from the dull round of desire, seduction, and disappointment that had dogged him from late adolescence. He would be transformed by that knowledge, wouldn’t he? No man could experience the profundity of such feeling and remain unchanged.

The bare bulb in the middle of the room dimmed and brightened. brightened and dimmed again. It had taken on the rhythm of the bell, burning its hottest on each chime. In the troughs between the chimes the darkness in the room became utter; it was as if the world he had occupied for twenty-nine years had ceased to exist. Then the bell would sound again, and the bulb burn so strongly it might never have faltered, and for a few precious seconds he was standing in a familiar place, with a door that led out and down and into the street, and a window through which—had he but the will (or strength) to tear the blinds back—he might glimpse a rumor of morning.

With each peal the bulb’s light was becoming more revelatory. By it, he saw the east wall flayed; saw the brick momentarily lose solidity and blow away; saw, in that same instant, the place beyond the room from which the bell’s din was issuing. A world of birds was it? Vast black birds caught in perpetual tempest? That was all the sense he could make of the province from which—even now—the hierophants were coming: that it was in confusion, and full of brittle, broken things that rose and fell and filled the dark air with their fright.

And then the wall was solid again, and the bell fell silent. The bulb flickered out. This time it went without a hope of rekindling.

He stood in the darkness, and said nothing. Even if he could remember the words of welcome he’d prepared, his tongue would not have spoken them. It was playing dead in his mouth.

And then, light.

It came from them: from the quartet of Cenobites who now, with the wall sealed behind them, occupied the room. A fitful phosphorescence, like the glow of deep-sea fishes: blue, cold, charmless. It struck Frank that he had never once wondered what they would look like. His imagination, though fertile when it came to trickery and theft, was impoverished in other regards. The skill to picture these eminences was beyond him, so he had not even tried.

Why then was he so distressed to set eyes upon them? Was it the scars that covered every inch of their bodies, the flesh cosmetically punctured and sliced and infibulated, then dusted down with ash? Was it the smell of vanilla they brought with them, the sweetness of which did little to disguise the stench beneath? Or was it that as the light grew, and he scanned them more closely, he saw nothing of joy, or even humanity, in their maimed faces: only desperation, and an appetite that made his bowels ache to be voided.

“What city is this?” one of the four inquired. Frank had difficulty guessing the speaker’s gender with any certainty. Its clothes, some of which were sewn to and through its skin, hid its private parts, and there was nothing in the dregs of its voice, or in its willfully disfigured features that offered the least clue. When it spoke, the hooks that transfixed the flaps of its eyes and were wed, by an intricate system of chains passed through flesh and bone alike, to similar hooks through the lower lip, were teased by the motion, exposing the glistening meat beneath.

“I asked you a question,” it said. Frank made no reply. The name of this city was the last thing on his mind.

“Do you understand?” the figure beside the first speaker demanded. Its voice, unlike that of its companion, was light and breathy—the v...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword: Armistead Maupin

- Private Legends: An Introduction

- One - Doorways

- Two - Journeys

- Three - Visions and Dreams

- Four - Lives

- Five - Old Humanity

- Six - Bestiary

- Seven - Love

- Eight - Terrors

- Nine - The Body

- Ten - Worlds

- Eleven - Making and Unmaking

- Twelve - Memory

- Thirteen - Art

- Appendix

- Permissions

- Acknowledgments

- Also by Clive Barker

- About the Author

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

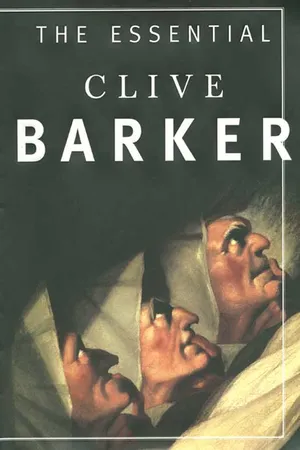

Yes, you can access The Essential Clive Barker by Clive Barker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatura & Literatura general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.