- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Civilization Of Ancient Egypt

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Civilization Of Ancient Egypt by Paul Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & History of Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

THE TAKE-OFF OF EGYPTIAN CULTURE

At one time scholars believed that the civilization of ancient Egypt was the first in the history of the world and the progenitor of all others. We now know this to be untrue, but the ancient Egyptians retain one unique distinction: they were the first people on earth to create a nation-state. This state, embodying the spiritual beliefs and aspirations of the Egyptian race, was in all its major manifestations a theocracy. It served as the framework of a culture of extraordinary strength, assurance and durability which lasted for 3,000 years and which retained almost to the end its own unmistakable purity of style. In the Egypt of antiquity, State, religion and culture formed an indisputable unity. They rose together; they fell together, and they must be studied together.

Moreover, there was a fourth essential element in this creative unity: the land. It is impossible to conceive of the civilization of ancient Egypt except in its peculiar geographical setting. It was nurtured and continued to be dominated right to the end by the physical facts of its setting: the rhythm of the Nile and its productive valley, and the circumscription of the desert. They gave the Egyptian people and their culture certain fundamental characteristics: stability, permanence and isolation. The Egyptians, indeed, were self-consciously aware of their national immobility and separateness. They assumed they had always inhabited the Nile valley as a distinctive race; and that the valley, with its enclosing deserts, had so existed since the Creation.

In fact neither assumption was correct: even Egypt and its people were subject to the slow transformations of time. At one time all Egypt, like most of Africa, was inhabitable. In the later part of the Middle Paleolithic Period, about 10,000 BC, there was an accelerating decline in local rainfall. The pastures and savannahs of the Egyptian plains became desert. Even as late as about 2350 BC, average rainfall in Egypt was much higher than today – up to six inches a year – but it was decreasing and continued to do so throughout historic times. Much of the country, therefore, became increasingly inhospitable to animals and men. The hippos, the gazelles, the buffaloes and ostriches gradually became fewer. Wild asses, wild cattle, ostriches and lions continued to be hunted well into the time of the pharaohs; Amenophis III boasted that in the first ten years of his reign (c. 1413–1403 BC) he had killed 102 lions with his own hand; and 200 years later, Ramesses III had carved onto the stone pylon of his temple at Medinet Habu the splendid panorama of a royal hunt for wild asses and bulls. There were, in fact, many hippos in the Nile delta even in Roman times. But, in general, the encroachment of the desert was inexorable, driving the fauna of the plains ever further to the south, and mankind to the desert oases and, above all, to the Nile valley.

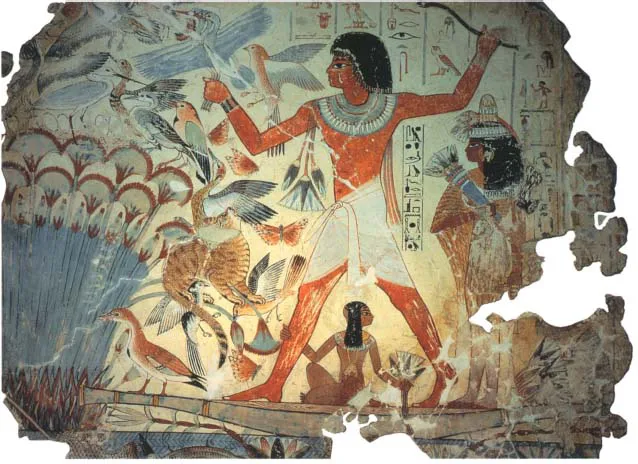

A fowling scene from the tomb of Nebamun, Thebes.

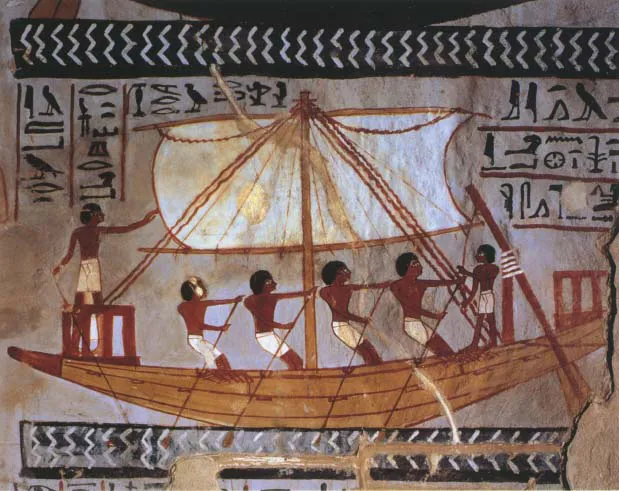

A river-boat steered by a stem-oar, from a fresco in the tomb of Sennufer at Thebes. Some Egyptian boats were built with the unsatisfactory wood of the sycamore.

The Nile seems to have begun to assume its present course about 10,000 years ago. At the time when the plains were drying up, the rainfall of the African forests and the melting snows of Ethiopia were creating its annual flood and transforming the great river into a geographical constructor. It drove its way through the granite rocks to the south of the First Cataract, through the sandstone stretching almost as far north as ancient Thebes, and then through the limestone plateau to the Mediterranean Sea. At the sea itself, it piled up the alluvial delta, and in the series of terraces and valley bottom it carved out of the rocks, spread with the alluvial soil carried down with the flood, it created a continuous oasis 750 miles long from the First Cataract to the sea.

As the savannah turned into desert, palaeolithic man began to descend to the Nile terraces and then to the valley bottom. Of course the valley was initially marsh. For many millennia, the tract from the First Cataract to Thebes was a lake; and much of the delta remained marsh throughout our period. But potentially this was rich agricultural land – 13,300 square miles in the valley itself, and a further 14,500 square miles in the delta. The Nile supplied not merely reliable water but equally reliable alluvial deposits and fertilization. By 5000 BC the palaeolithic hunters of the plains had transformed themselves into the neolithic farmers and herdsmen of the valley and delta, and the agricultural economics of historic Egypt had taken shape. What remained to be done was to complete the conquest of the marshland and to begin the harnessing of the river, by dyke, barrier, basin and canal – and therein lies the story of the Egyptian State, and the culture it begot.

The Nile alluvium makes the soil black. From the very earliest times, the Egyptians divided their country into ke me, the black – that is, the cultivable, inhabitable part – and deshret, the red or desert. Such dualism seems to have been part of the Egyptian character. The country itself was seen as divided into two distinct halves: the Valley or Upper Egypt, and the Delta, or Lower Egypt; and the Delta in turn into a western, or Libyan, and an eastern, or Asian, half. The physical configuration of Egypt was completed by its external barriers: the cataracts cut if off to the south, the Libyan desert to the west, the Eastern Desert, the Red Sea and the Sinai Desert to the east, and the Delta, which with its marshes and myriad, ever-shifting channels, constituted as much an obstacle as an exit, to the north.

Thus isolated from the world beyond, Egypt was dominated by the seasonal rhythms of its river. Not only the river but the inundation itself, termed Hapy, was worshipped as divine. Hapy was bearded, with water-plants sprouting from his head, and with female breasts, symbolizing fertility, hanging from his body. The Egyptians believed that he drew his power, that is the waters of the flood, from underground basins around the First Cataract and long after this explanation had been shown to be false they worshipped the gods of this region fervently. And so they might, for the Nile is perhaps the most beneficent and dependable great river on earth. The conjunction of its two sources, the White and the Blue Nile, and its long journey through the plateau, give the annual flood the character of a reliable annual system rather than an unpredictable catastrophe.

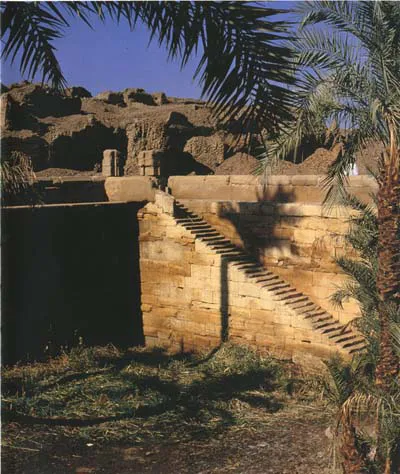

Egyptian civilization was growing up at roughly the same time as that of Mesopotamia, another alluvial valley-plain. But whereas the Tigris and Euphrates brought savage and irregular destruction, as well as life, and so imparted to the cultural philosophy of the people an element of insecurity and pessimism, the Nile was not a fury but a friend. Of course its performance varied, as it still does. Between low water and flood, the volume of water in the Blue Nile, for instance, rises from 7,000 cubic feet per second to over 350,000 on average; and within this average there is considerable variation. At Elephantine, near the First Cataract, and at Old Cairo, where the Valley effectively joins the Delta, the ancient Egyptians set up stone markers, or Nilometers, by the riverside, to record and to some extent predict the river’s behaviour. The evidence of these venerable devices shows that a rise of twenty-one feet was dangerously low, twenty-eight or more would bring damaging floods, and some twenty-five to six feet was desirable, or ‘normal’. Until the recent construction of high dams, the river behaved much the same as it did in antiquity. It began to rise between Aswan and the Delta in June, when green water appeared. The river rose sharply in August and became reddish-coloured. The rising continued until mid-September and then, after a three-week pause, rose again in October; thereafter it fell slowly throughout the winter and spring, until the lowest point was again reached the following May.

Pool and Nilometer at Dendera, Egypt.

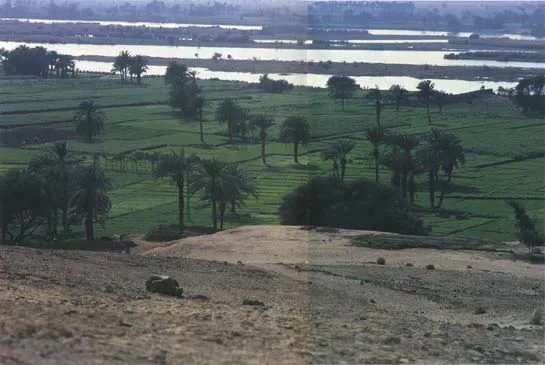

The Nile landscape, provider of transport and fertility for agriculture.

This slow, deliberative and predictable annual river-cycle was and is accompanied by an exceptionally regular climate. The skies in Egypt are sunny and cloudless. Rainfall in Upper Egypt is virtually nil; it is about two inches a year in the Cairo area, and about six, or a little more, in the Delta, these rains falling in winter. The combination of reliable sunshine and adequate water (plus natural fertilizer) makes for highly successful crops. Herodotus, writing in the fifth century BC, asserted that the Egyptian peasant had an easy time of it. This was not true: at certain times of the year, especially after the flood water subsided, he worked extremely hard. It was when the waters fell that the agricultural year began, and planting had to be rapid while the earth was still soft; at the same time all the multitude of ditches and canals had to be cleared out and repaired. The crops ripened under the winter sun and were harvested in the spring while it was still cool; the process had to be completed by the end of May, when the waters rose again. There were thus three seasons in the agricultural year: flood, sowing and harvest; and it was fortunate for the Egyptians that the flood, when there was least to be done, coincided with the hottest weather.

The river provided not only fertility but transport. The inhabited land of the Valley varied from about five to fifteen miles in width. This was where all the basic crops, emmer wheat, barley and flax, were grown. The Delta, chiefly used for pasture, was bisected by innumerable channels, running from north to south. Every part of Egypt where men lived and worked was within a few miles of river transport. Thus the wheel came late to Egypt. We find it on an early depiction of a siege-ladder, but not on carts. Wheels had been in use in Mesopotamia for a thousand years before chariots were common in Egypt. All the same, thanks to the river, Egypt had the best internal communications of any country of antiquity. From the moment when they descended from the Nile terraces the Egyptians built river-boats, using with considerable ingenuity the unsatisfactory wood of the sycamore, the only tree the country produced in any abundance. Boats steered by stern-oars could descend the river, travelling with the current, throughout the year, even at times of low water. Rafts and barges could and did travel down-river with colossal weights of stone aboard; and during the flood, in late summer and autumn, they could easily deliver their burdens to points several miles above the low-water mark. It was the river which made the logistics of Egypt’s ponderous stone culture not only possible but comparatively cheap. And transport upstream too was cheap, for the prevailing wind in Egypt blows throughout the year from the north, another example of the beneficence of nature. Oars needed only to be used during the infrequent periods of total calm, for the Egyptians quickly developed the highly efficient triangular sails still in use today, which catch the slight but persistent north breezes. In Egyptian hieroglyphic script, the determinative ‘go north’ is a simple boat, and ‘go south’ a boat with a sail.

Hence, despite the desiccation of Egypt, the Nile made it one of the most desirable regions on earth for ancient man. Yet in prehistoric times, this enormous natural advantage was an inducement to improvement rather than lethargy. The Nile never failed, but it was sometimes sparing. The early Biblical story of Joseph and the seven lean years following the seven years of plenty, which refers to a date in the Second Intermediate Period itself, reflects a much more ancient Egyptian tradition of seven consecutive low Niles. The waywardness of the river was a spur to organization, and to the creation of a storage economy – the river itself making it possible to ship grain easily from one end of the country to the other. Even more important, the river was a perennial spur to extending the area which was drained and irrigated. This too involved powers of organization and much hard labour.

What Herod...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- CONTENTS

- MAPS

- CHAPTER ONE: THE TAKE-OFF OF EGYPTIAN CULTURE

- CHAPTER TWO: THE TOTALITARIAN THEOCRACY

- CHAPTER THREE: THE EMPIRE OF THE NILE

- CHAPTER FOUR: THE STRUCTURE OF DYNASTIC EGYPT

- CHAPTER FIVE: THE DYNASTIC WAY OF DEATH

- CHAPTER SIX: HIEROGLYPHS

- CHAPTER SEVEN: THE ANATOMY OF PRE-PERSPECTIVE ART

- CHAPTER EIGHT: THE DECLINE AND FALL OF THE PHARAOHS

- CHAPTER NINE: THE REDISCOVERY OF THE PHARAOHS

- SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX

- BY THE SAME AUTHOR

- Copyright

- About the Publisher