eBook - ePub

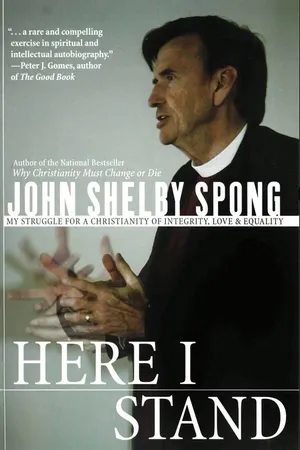

Here I Stand

My Struggle for a Christianity of Integrity, Love, and Equality

- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Here I Stand by John Shelby Spong in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Religious Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Setting the Stage: The Parameters of the Debate

“Your words are not just heresy, they are apostasy. Burning you at the stake would be too kind!”

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

“Your book was like manna from heaven—God-sent! I cannot adequately express my gratitude.”

Richmond, Virginia

“You rail against the Church’s doctrines and core beliefs while you accept wages from her. Even whores appreciate their clients. You, sir, have less integrity than a whore!”

Selma, Alabama

“You have made it possible for me to remain in the Church and have taught me how to believe honestly its creeds even in the twentieth century.”

Boston, Massachusetts

“Bishop Spong, you are full of sh-t. We are going to clean you up.”

An orthodox Christian

“Reading your book is like eating a delicious Black Forest cherry birthday cake. It has made me vulnerable while increasing my desire to worship.”

British Columbia, Canada

“Remember, as you prance about disguised as a minister of the gospel, that you will pay for your sins eternally in the lake of fire.”

Charleston, South Carolina

“Your book is a transcendent work of brilliance and, I am sure, permanence.”

Pasadena, California

“I hope the next plane on which you fly crashes. You are not worthy of life. If all else fails, I will try to rid the world of your evil presence personally.”

Orlando, Florida

“I believe you are a prophet and I will strive with you to answer God’s call to live fully, love wastefully, and be all that I can be. Thank you, thank you, and may your life continue to be blessed.”

Grosse Point, Michigan

THESE ARE excerpts from but a tiny few of literally thousands of letters I have received in my career as a bishop. They clearly reveal the diversity of responses my life, ministry, and writings have elicited over the years. If someone had told me years ago that I would create these enormous levels of both appreciation and hostility in my ordained life, I would have been dumbfounded, shocked, and probably deeply hurt. How did it happen? What created these twin emotions of praise and anger, of gratitude and fear? What forces pushed me, compelled me, or led me to play my particular role in the struggle to make the Christian Church respond to the issues of our century, and indeed to open new dimensions of spirituality to the citizens of this century? That is the story I seek to tell.

March 6, 1976, was a crisp, sunny late winter Saturday in Richmond, Virginia. It fell in the midst of a busy weekend in my life. On Friday, the fifth, I had indulged my passion for sports and secured, through my politically well connected cousin, tickets to the semifinals of the Atlantic Coast Conference basketball tournament, which was being played in Landover, Maryland. My alma mater, the University of North Carolina, was playing my daughters’ alma mater, the University of Virginia, in one of the two semifinal games on that date. To be a Tar Heel while living in Virginia and serving St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, the historic “Cathedral of the Confederacy,” in downtown Richmond made me about as popular as Kentucky Fried Chicken’s Colonel Sanders at a chicken farm. The commitment of old-line Virginians to the Cavaliers of the University of Virginia was deep. Even my two older daughters would choose to go to the University of Virginia and to be grafted into the Virginia tradition. So I watched this particular game in a sea of Virginia alumni. One of them, sitting just behind me, was my friend Sidney Buford Scott, whose family had given Scott Stadium to the University of Virginia and Scott Lounge to the Virginia Theological Seminary. He was one of the few in those stands who was aware that I was at that moment a nominee for the position of bishop coadjutor of the Diocese of Newark in the state of New Jersey and the choice would be made the next morning. That night, as my university was being eliminated by his, he inquired about that process.

“Any chance you’ll be elected?” he asked.

“Somewhere between slim and none.” I replied. “I believe I’ll get enough votes not to be embarrassed, but not nearly enough to be elected. It’s not something in which I have any great investment.”

That was an honest assessment. That was also the only time that evening that the Newark election entered my consciousness.

The Sunday of that same weekend was also to be a big day in my life. I was engaged in a series of dialogue sermons that were to last for three Sundays on the wide-ranging subject of medical ethics. This was my attempt to address theologically a concern that had been brought to the public’s attention by the case of one Karen Quinlan, who had been in a coma for months, kept alive by mechanical devices. Her parents had petitioned the courts for permission to remove these artificial support systems and allow this young woman, their child, to die. The courts had refused this request, and a national debate had ensued.

St. Paul’s Church in Richmond was only three blocks from the Medical College of Virginia. We had over eighty doctors in the congregation. Occasionally I used the sermon period for a dialogue on vital public issues. This allowed me to invite people who possessed an expertise that I did not to engage both me and the congregation in debate. Whether a hopelessly brain-dead young woman should be kept breathing by medical devices seemed tailor-made for such an approach. A young internist associated with the Medical College of Virginia and active at St. Paul’s named Daniel Gregory had agreed to be the medical member for this dialogue. I was cast in the role of the Christian ethicist. Using the Karen Quinlan case as the point of entry, we hoped to extend the debate to the beginning of life, addressing abortion and birth control, as well as to the far side of life, where we hoped to examine active and passive euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. There had been good response to these initiatives as the dialogue unfolded. These Sunday events were widely covered by the local press, radio, and television and had succeeded in what was always my primary agenda as a priest, namely, to move the theological debate out of the structures of sacred space and into the homes and professional lives of our people. To have a sermon discussed during the week in offices and hospitals, on golf courses, at bridge tables, and at cocktail parties was my measure of successful preaching. This dialogue had been particularly engaging, since Dan Gregory was a thoughtful and articulate representative of the medical community.

At about 11:45 on that Saturday morning I was in my office at the church with Dan Gregory and Lucy Boswell Negus working on the details of the Sunday presentation. Lucy Negus, our administrative assistant, was a particularly gifted and helpful member of my staff who had assisted me in every book I had written. She was an exquisite editor and a published poet who had just that previous fall transformed about two years of my sermons into free verse for publication by a local Richmond publisher in an elegant coffee-table book entitled Christpower. She was there to help Dan and me put the final literary touches on the dialogue so that it would stimulate the debate we desired. It was a comfortable, easy, exciting, fun morning with two people whose company I thoroughly enjoyed. That was the setting interrupted by the telephone message that would redirect the balance of my life.

“Hi, Jack! This is Joe Herring,” was the cheery greeting of the interrupter. Joe Herring was a priest in the Diocese of Newark, serving as the rector of St. Stephen’s Church in Millburn. I had not known him prior to my nomination. For reasons not altogether clear to me, he and another priest, Phillip Cato, had decided that I was the person they wanted to be elected bishop, and so they had become my unofficial “campaign managers.” Indeed, they were far more eager to elect me than I was to be elected, but I was touched by their interest and did not object to their doing what I thought was tilting at windmills. Joe’s voice on the other end of the line was now noticeably excited. His words poured out.

“We’ve just completed the sixth ballot,” he stated. “You have been elected in the lay order since the fourth ballot. In the clergy order you are one vote short of an election. Herbert Donovan has just asked to have his name withdrawn from further consideration and has stated publicly his intention to vote for you on the seventh ballot. That means you will be elected, Jack!”

It was more than I could register at that moment. Herb Donovan was the rector of St. Luke’s Church in Montclair, New Jersey. He was one of the three clergy in the Diocese of Newark I had known prior to the nomination, a friend since seminary days. My impression was that he was the clear clergy leader of the diocese. He was an elected member of the Standing Committee, the highest governing body in the diocese. He was also an elected deputy to the general convention, a prestige position for clergy, and he had been one of two official “in diocese” nominees for bishop coadjutor. He was supported by both the retired bishop of Newark, Leland Stark, and the diocesan bishop, George E. Rath. When I had gone to New Jersey to be interviewed by the nominating committee, I had stayed with Herb. He and his wife, Mary, were gracious hosts and lovely people. On those visits he and I had discussed the election. I knew almost nothing about the inner dynamics of diocesan life in Newark. He was obviously well informed, and I was convinced that he would be elected. He loved church politics and was destined to play a significant role in the life of our church in the following years.

With Herb so clearly the favorite in my mind, I had allowed myself to develop little emotional energy during the election process. That was easy for me to do, since I was happy and fulfilled in my life in Richmond. I had written four books and a fifth one was at that moment under contract and in preparation. My orbit of travel as an invited lecturer and guest preacher was expanding. I was eager to be not a bishop, but another Walter Russell Bowie or Theodore Parker Ferris, two men I greatly admired for their shaping of the church through their writing and preaching as priests. For that reason I had been reluctant for some time to enter the episcopal process.

In 1975 I had agreed to be nominated in the Diocese of Delaware, but had withdrawn the night before the election. I had not been able to develop any enthusiasm for that position and thought it unfair to the people in Delaware to allow them to consider and even to vote for so reluctant a candidate. Part of my willingness to enter the Newark process a year later came from my conviction that I had no chance of being elected in that diocese, and I thought it would cleanse me of the negativity that always surrounds the withdrawal of a publicly acknowledged nominee for the office of bishop.

Yet, as I put the phone down that Saturday morning, it seemed obvious that, whether I wanted it or not, this was now to be my destiny. I tried to call my wife, Joan, but there was no answer. I then shared the call with my two office companions, Lucy and Dan. How they reacted inside I do not know. I do know that this news put an end to our preparation for the next day. We talked about what it might mean. They were both kind and gentle. We kept reminding ourselves that it was still quite unofficial, but it didn’t work. In less than twenty minutes the phone rang again.

“Jack, this is George Rath. I want to congratulate you on being elected bishop coadjutor. I look forward to working with you.” There were other words that passed between us that morning, I am sure, but they were lost in the fog of what was for me a kind of swirling of emotions and a surprising sense of depression. I placed the phone down. I did not have to say a word to my good friends. They understood that this was the confirming call. I shook Dan’s hand and embraced Lucy. They both departed quickly and left me alone to sort out my thoughts.

I then called my closest friend, John Elbridge Hines. He was the retired presiding bishop of our church. I visited with him weekly by phone and had spent a considerable portion each of the preceding three summers with him at his home in Highlands, North Carolina. A deep bond between us had developed. He now was the primary person with whom I wanted to discuss this matter. He answered the phone himself, not with “Hello,” but with the familiar words, “John Hines.”

“John, this is Jack,” I stammered. “I’ve just been elected bishop coadjutor of the Diocese of Newark.”

John was pleased. I had clearly become his protégé, and he knew the Diocese of Newark well. He did not pull his punches, however.

“Jack, that may be the most difficult position in the whole church. The urban areas of New Jersey—Newark, Paterson, Jersey City, Camden, and Trenton—are among the most desperate in America. The social fabric of those cities is all but dysfunctional. You will succeed two good bishops in Leland Stark and George Rath, and yet Leland’s health was broken by that position and George survived by not engaging the issues. You are a strong person, Jack, but this position will test everything you have. You also need to recognize that the New York area is the communications center of the world. If you do this task well in that location, everyone will know it. If you stumble and fall, everyone will know that also. But I’m very pleased for you and for the church!”

It was a typical John Hines statement—straightforward, honest, blunt, and helpful.

A couple of hours later I had a call from John Maury Allin, the present presiding bishop. I was an elected member of the executive council, the highest governing body, of the national church, so I knew this man well. Jack Allin was a radically different person from John Hines. He had been chosen for this position as a strong reaction to John’s fearless and aggressive leadership. He was far more an institutional-maintenance bishop than a prophet. His self-projection was that of a pastor to a divided and hurting church. I experienced him as a deeply partisan person with little or no capacity to embrace reality beyond his perception of it. He also had tremendous control needs. He had positioned himself as the chief voice opposing John Hines and had ridden that image to win the election as John’s successor.

To say the least, we were not close. To his credit, in his first conversation with me as a bishop-elect, honesty prevailed over duplicity. With false laughter designed to cover his negativity, he said, “When I heard the news, I said, ‘Dear God, the church does not need this!’” It was a bit startling, even for him. I did not help the situation with my response.

“That’s interesting, Jack,” I said, returning the false laughter. “That’s exactly what I said when I heard you had been chosen presiding bishop.”

I had, in fact, been part of the three-hour debate in the House of Deputies over whether to confirm his election. I voted against confirmation, but I did not prevail. The lines were clear. The same church that had elected him had now also elected me. It had to be a church big enough to embrace us both, but we would always march to the beat of different drummers. We represented two diametrically opposite approaches to ministry in the twentieth century. Jack would leave the primate’s office in 1985. I would depart the episcopal office in 2000. Yet, though the content of the debate would shift, the points of view we each represented would contend through all of those years and would define the life and role of the church as we entered the third millennium. I clearly came to represent one polarity and Jack Allin the other in the church’s struggle for relevance, life, and meaning. The dance we were to conduct, bound together by our love for the church, yet seeking to pull that church in very different directions, was the result of many, many factors over which neither of us had ultimate control. Both of us had deep Southern roots. He was born in Arkansas and I was a child of North Carolina. He was the bishop of Mississippi before moving to the national scene as the presiding bishop, a role that inevitably gave him an international stage. I was a Southern rector elected to be the bishop of Newark in the metropolitan New York area, but my life as an author also gave me both a national and even an internation...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Searchable Terms

- Photo Insert

- About the Author

- Other Books by John Shelby Spong

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher