eBook - ePub

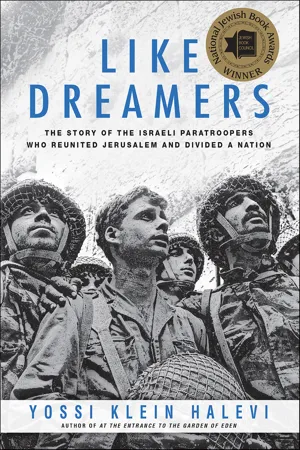

Like Dreamers

The Story of the Israeli Paratroopers Who Reunited Jerusalem and Divided a Nation

- 624 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Like Dreamers

The Story of the Israeli Paratroopers Who Reunited Jerusalem and Divided a Nation

About this book

"Powerful. . . . beautifully written . . . . There is much to admire . . . especially Mr. Halevi's skill at getting inside the hearts and minds of these seven men" —Ethan Bronner,

New York Times

Following the lives of seven young members from the 55th Paratroopers Reserve Brigade, the unit responsible for restoring Jewish sovereignty to Jerusalem during the 1967 Six Day War, acclaimed journalist Yossi Klein Halevi reveals how this band of brothers played pivotal roles in shaping Israel's destiny long after their historic victory. While they worked together to reunite their country in 1967, these men harbored drastically different visions for Israel's future.

One emerges at the forefront of the religious settlement movement, while another is instrumental in the 2005 unilateral withdrawal from Gaza. One becomes a driving force in the growth of Israel's capitalist economy, while another ardently defends the socialist kibbutzim. One is a leading peace activist, while another helps create an anti-Zionist terror underground in Damascus.

Featuring eight pages of black-and-white photos and maps , Like Dreamers is a nuanced, in-depth look at these diverse men and the conflicting beliefs that have helped to define modern Israel and the Middle East.

"A beautifully written and sometimes heartbreaking account of these men, their families, and their nation." — Booklist, starred review

"Halevi's book is executed with imagination, narrative drive, and, above all, deep empathy for a wide variety of Israelis, and the result is a must-read for anyone with an interest in contemporary Israel and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. — Publishers Weekly, starred review

"Mr. Halevi's masterly book brings us into [the] . . . debate and the lives of those who live it." —Elliott Abrams, Wall Street Journal

Following the lives of seven young members from the 55th Paratroopers Reserve Brigade, the unit responsible for restoring Jewish sovereignty to Jerusalem during the 1967 Six Day War, acclaimed journalist Yossi Klein Halevi reveals how this band of brothers played pivotal roles in shaping Israel's destiny long after their historic victory. While they worked together to reunite their country in 1967, these men harbored drastically different visions for Israel's future.

One emerges at the forefront of the religious settlement movement, while another is instrumental in the 2005 unilateral withdrawal from Gaza. One becomes a driving force in the growth of Israel's capitalist economy, while another ardently defends the socialist kibbutzim. One is a leading peace activist, while another helps create an anti-Zionist terror underground in Damascus.

Featuring eight pages of black-and-white photos and maps , Like Dreamers is a nuanced, in-depth look at these diverse men and the conflicting beliefs that have helped to define modern Israel and the Middle East.

"A beautifully written and sometimes heartbreaking account of these men, their families, and their nation." — Booklist, starred review

"Halevi's book is executed with imagination, narrative drive, and, above all, deep empathy for a wide variety of Israelis, and the result is a must-read for anyone with an interest in contemporary Israel and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. — Publishers Weekly, starred review

"Mr. Halevi's masterly book brings us into [the] . . . debate and the lives of those who live it." —Elliott Abrams, Wall Street Journal

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

THE LIONS’ GATE

(MAY–JUNE 1967)

Chapter 1

MAY DAY

THE SOCIALISM OF “THE GANG”

IN THE ORANGE orchards of Kibbutz Ein Shemer, Avital Geva, barefoot and shirtless in the early-morning sun, was frying eggs in a blackened pan. Turkish coffee was boiling in the aluminum pot, and his friends were laying out plates of tomatoes and cucumbers and olives, white cheese and jam. “Ya Allah, what a feast!” exclaimed Avital, as if encountering for the first time the food he had eaten for breakfast every day since childhood.

It was mid-May 1967. Avital and his crew had been working since dawn, to outwit the heat of the day. Rather than return to the communal dining room for breakfast, the young men allowed themselves the privilege of eating together beneath the corrugated roof they’d erected for just that purpose. Could there be greater joy, thought Avital, than working the fields with one’s closest friends and sharing food grown by their kibbutz?

One could almost forget about the crisis on the Egyptian border.

Late spring was Avital’s favorite time in the orchards. The air was heavy with trees in flower. The last of the Valencia oranges had just been harvested, and the first swellings appeared of what would be the autumn harvest. Meanwhile the orchards had to be prepared for the long, dry summer. Every morning the crew dragged two dozen irrigation pipes, each six meters long, from row to row. Though only twenty-six years old, Avital had been appointed head of the orchards, one of the kibbutz’s main sources of income. Ein Shemer’s orchards were among the country’s most productive. Avital experimented with new machinery that would increase the harvest without entirely mechanizing the process, preserving a tactile encounter with the fruit. If you don’t say good morning to the tree, he had learned from the old-timers, the tree won’t say happy new year to you. Avital could spend an entire morning pruning a single tree, satisfying his artistic longings. “Michelangelo,” his friends called him, and half meant it.

Work in the orchards, Avital insisted, should be fun. When the kibbutz’s high school students were sent to help with the harvest, Avital dispatched tractors to retrieve them from their dormitories and gave them the wheel. Awaiting them in the orchards were bins of biscuits; during breaks, he made French fries, an extravagance in a kibbutz whose diet was determined by austere Polish cooks. He divided the young people into teams, and the one that filled the most bins won chocolate.

Avital’s close-cropped hair exposed an expression at once tender and resolute. The lower lip protruded, and a sturdy chin rose to uphold it. His blue eyes seemed translucent.

“Hevreh?” he called out. “The eggs are ready!” Avital turned ordinary words into superlatives. And for Avital no word was more urgently joyful than hevreh—the gang—which he sang and elongated with new syllables. For Avital, hevreh was a kind of miracle, transforming separated beings into a single organism bound by common purpose, by love. The essence of kibbutz: a society of hevreh, in which no one was extraneous. Like poor Meir, heavy and sluggish, an Egyptian Jew lost among the Polish Jews of Ein Shemer, who’d been shunted from one part of the kibbutz workforce to the other until Avital insisted he join the hevreh in the orchards. And when they went on a bicycle trip up the steep hills to Nazareth, they brought Meir along, installing him like a peasant king on a couch mounted on a tractor-drawn wagon.

Banter around the breakfast table turned to the situation in the south. The crisis had begun a few days earlier, on Israel’s Independence Day, when Egyptian president Nasser announced that he was dispatching troops toward the Egyptian-Israeli border. Then he ordered UN peacekeeping forces to quit the border, and incredibly, the UN complied. Now Egyptian troops and tanks were taking their place. Radio Cairo and Radio Damascus were broadcasting speeches by Arab leaders promising the imminent destruction of Israel.

“Why aren’t they calling us up?” demanded Avital, a lieutenant in the 55th Brigade, the reservist unit of the elite paratroopers. How could he be sitting here while the country faced a threat to its life?

“Maybe there will be a diplomatic solution,” someone suggested.

“Not with the Russians pushing the Arabs to war,” someone else added. “When my two friends were killed by the Syrians, the Russian ambassador in the UN said that Israelis killed Israelis to blame the Syrians. That’s when I finished with Mother Russia.”

“Mother Russia,” Avital repeated with contempt.

AS A CHILD, Avital had been confused about Marxism and the Soviet Union, and on Kibbutz Ein Shemer, that was a pedagogical problem. Ein Shemer belonged to the Marxist Zionist movement Hashomer Hatzair (the Young Watchman). Avital and his friends had been raised to revere the Soviet Union as the “second homeland,” as movement leader Yaakov Hazan once put it. Beginning in second grade they were taught Marxist principles by rote. “An avant-garde alone cannot create a revolution!” they chanted. But what exactly was an avant-garde, wondered Avital, and what was its relationship to the children of Ein Shemer? The words seemed too big for him; he could hardly pronounce them. Other children seemed to readily grasp the difference between deceptive socialism and true communism; why couldn’t he?

He was twelve years old in 1953 when Stalin died. Ein Shemer went into mourning. The annual satirical play performed on the spring holiday of Purim was canceled. The movement’s newspaper, Al Hamishmar (On Vigilant Watch)—whose logo read, “For Zionism—For Socialism—For the Fraternity of Nations”—spread across the front page a heroic image of Stalin, his stern gaze focused on a distant vision. “The Progressive World Mourns the Death of J. V. Stalin,” read the banner headline.

Of course Stalin’s death saddened Avital, but however terrible to admit, it seemed abstract to him. What did he really have to do with this man with the big mustache and row of medals on his chest? At Ein Shemer’s memorial, they played a recording of Stalin’s speech marking the victory over Nazism, but it was in Russian, and Avital couldn’t understand the words.

A few years later, when a new Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, came to power and repudiated Stalinism, Hashomer Hatzair acknowledged that Stalin had made mistakes, even committed crimes. But lest we forget, insisted the ideological guides of the movement, it was not easy transforming a country of peasants into a communal society. The kibbutz and the Soviet Union were different aspects of the same historical march: the kibbutz an experiment in pure communism, the Soviet Union an experiment in mass communism. Both were necessary to prove the practicality of radical equality. And lest we forget: Stalin defeated Hitler, and the Red Army liberated Auschwitz. And in 1948 the Soviets had supported Jewish statehood and shipped Czech weapons to the IDF.

Avital was not indifferent to the Soviet romance: just as Europe had produced the ultimate evil, how right that it should produce the ultimate good. The weekly films screened on the kibbutz included Soviet-made features about the Red Army’s struggle against Nazism. Though the Hebrew subtitles were often out of sync with the images, watching those films was thrilling. In one, a Soviet soldier threw himself against a German machine-gun post, allowing his comrades to conquer the position.

Sometimes Hazan—as everyone in the movement called Yaakov Hazan, revered leader of Hashomer Hatzair—would visit Avital’s parents, old friends from Warsaw. Avital would eavesdrop on their conversation about the latest “important and fateful matter,” as Hazan put it, before slipping away in boredom. Afterward, what he’d recall wasn’t Hazan’s analysis but the warmth with which Hazan and his parents interacted, without any sense of distance. Just like the two Ein Shemer comrades who happened to be members of the Knesset but who took their turn like everyone else serving in the dining room.

Avital loved Ein Shemer, with its modest members riding rusty bicycles in their work clothes and kova tembel, the brimless, floppy “fools’ hat” whose very name was self-deprecating. Almost everything here had been planted or built by their own hands. Everyone was valued for who they were, not only for what they did.

For the founders of Ein Shemer, physical labor was an act of devotion, virtually a religious ritual. Working the land of Israel became a substitute faith for the Jewish tradition they abandoned; the socialist Zionist poet Avraham Shlonsky compared the roads being built by pioneers to straps of phylacteries, and the houses to its black boxes. The kibbutz transformed holidays from religious events into celebrations of the agricultural cycle, just as they were in ancient Israel, except without God. Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish year but which lacked agricultural symbolism, was just another workday on Ein Shemer.

SONG OF THE FOREST

WITH SEVERAL HUNDRED members and no industry, Ein Shemer, located near the coast between Tel Aviv and Haifa, wasn’t one of the larger or more prosperous kibbutzim. But nothing here felt provincial to Avital. Big issues informed daily conversation. Ein Shemer’s members included high-ranking officers, pilots, paratroopers. No kibbutz, they boasted here, produced more writers.

And none, thought Avital, was more beautiful. The entrance to Ein Shemer was lined on either side with ficus trees whose branches reached toward each other and formed a canopy. Nearby was the old courtyard, a remnant of the kibbutz’s early years, a long stone house protected by a stone wall. No one lived there anymore, but it was preserved as a memory of Ein Shemer’s heroic origins, when the kibbutz was condensed to a single building surrounded by parched fields, a place so forlorn the comrades joked that their clocks lagged behind real time but no one noticed. The kibbutz had since evolved into rows of red-roofed houses, some with verandas; tomato and cotton fields, orange orchards, cowshed and chicken coops. The smell of cow dung mingled with orange blossoms and fresh-cut hay. A contiguous lawn spread across the sloping terrain, linking the parents’ area and the children’s area in a single public space.

Ein Shemer’s neighbors were Arab Israeli villages in the area known as the Triangle, and the Jordanian border was only a few kilometers away; but Avital grew up with a sense of safety. As soon as the last rains ended around Passover, the children went barefoot and didn’t put on shoes again until the first rains of autumn. In winter they ate oranges and grapefruits off the trees; in summer they roasted fresh-picked corn on campfires. Work and play were interchangeable: the children would be placed atop a pen filled with just-picked cotton and jump up and down until it flattened, while a comrade played the accordion. They learned to cherish the hard beauty of the land of Israel, wildflowers growing in porous stone, meager forests of thin pines clinging to rocky slopes. One day, during school hours, a teacher rushed from class to class and summoned the children outside: an oriole had been spotted. Everyone quietly filed out and watched until the bird flew away.

AT AGE FOURTEEN, Avital was chosen by Hashomer Hatzair to become a counselor, leading a group of the kibbutz’s eleven-year-olds. Other counselors told their scouts about the Rosenbergs, the accused atomic spies executed by the American government, but Avital felt incompetent to lead a political discussion.

Instead Avital emphasized the movement’s other values, love of land and hevreh. He led his scouts on hikes, singing all the way. “El hama’ayan!” he called out: To the spring! “To the spring!” his scouts repeated. “Came a little lamb,” Avital sang. “Came a little lamb,” voices echoed. When one of the children wearied, Avital carried him on his back.

“Listen, hevreh,” he told his twenty scouts one evening. “I’m going to set up camp in the forest, and you’re going to have to find me.” The forest was three kilometers away from the kibbutz. But how will we find you? the children protested. “There’s a full moon,” Avital said, smiling. “Just follow the music of the forest.”

He went ahead and, when he came to a clearing, retrieved from his knapsack a cordless phonograph and a recording of Mendelssohn’s Fingal’s Cave. As the music played, he began a campfire. Soon the scouts appeared, drawn by the music and the fire.

AYN RAND IN EIN SHEMER

THERE WAS ONE threat to Avital’s harmonious world: his father, Kuba, Ein Shemer’s architect. Kuba had taught himself the basics of architecture and had planned almost every structure in Ein Shemer from its founding in 1927; later the kibbutz sent him for two years of formal study abroad. Even among the driven pioneers of Ein Shemer, Kuba was relentless. He crammed a drafting table into the tiny room he shared with his wife, Franka, and which was barely large enough to contain bed, table, and dresser. When Avital would visit from the young people’s communal house, he would find Ku...

Table of contents

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Who’s Who

- Introduction: June 6, 1967

- PART ONE: THE LIONS’ GATE (MAY–JUNE 1967)

- PART TWO: THE SEVENTH DAY (1967–1973)

- PART THREE: ATONEMENT (1973–1982)

- PART FOUR: MIDDLE AGE (1982–1992)

- PART FIVE: END OF THE SIX-DAY WAR (1992–2004)

- Acknowledgments

- An Excerpt from Letters To My Palestinian Neighbor

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

- Also by Yossi Klein Halevi

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Like Dreamers by Yossi Klein Halevi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.