eBook - ePub

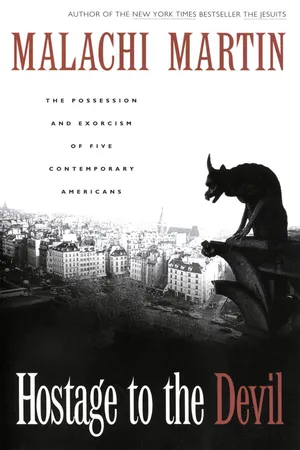

Hostage to the Devil

The Possession and Exorcism of Five Contemporary Americans

- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

The Cases

Zio’s Friend and the Smiler

Peter took one more breath of fresh air. He was reluctant to pull the open window shut against the uproar on 125th Street 15 stories below. It was the first time in history that a Roman Pope was driving through New York streets, and the very air was alive with excitement. The Pope’s motorcade had already passed over Willis Avenue Bridge into the Bronx on its way to Yankee Stadium. The crowds were still milling around. Some nuns scurried about like frenzied penguins blowing whistles and marshaling lines of white-clad schoolgirls. Hot-dog vendors shouted their prices. A dowdily dressed young woman and her child peddled plastic little popes to passersby. Two policemen were removing wooden barriers. A garbage truck snorted and honked its way through the traffic. Father Peter closed the window finally, drew the curtains together, and turned back toward the bed.

The room was quiet again, except for the irregular breathing of twenty-six-year-old Marianne. She lay on a gray blanket thrown over the bare mattress. With her faded jeans, yellow body-shirt, auburn hair straggling over her forehead, the pallor of her cheeks, and the aging, off-white color of the walls around her, she seemed part of a tragically washed-out pastel. Except for a funny twist to her mouth, her face had no expression.

To Peter’s left, with their backs to the door, stood two bulky men. One: an ex-policeman and a friend of the family, a veteran of 32 years on the force, where, he thought, he had seen everything. He was about to find out that he hadn’t. Sixtyish, balding, clad in dungarees, his arms folded over his chest, his face was a picture of puzzlement. The other: the closest acquaintance of Marianne’s father, whom the children called uncle, was a bank manager and a grandfather in his midfifties, red-faced and jowled, in a blue suit, his arms hanging by his sides, eyes fixed on Marianne’s face with an expression of helpless fear. Both these men, athletic and muscular, had been asked to assist at the exorcism of Marianne K., to quell any physical violence or harm she might attempt. Marianne’s father, a wispy man with reddened eyes and drawn face, stood with the family doctor. He was praying silently. Peter always insisted on having a member of the family present at an exorcism. As if in contrast to the others, the young doctor, a psychiatrist, wore a concentrated, almost studious look as he checked the girl’s pulse.

Peter’s colleague, Father James, a priest in his thirties, stood at the foot of the bed. Black-haired, full-faced, youthful, apprehensive, his black, white, and purple robes were a uniform for him. On Peter, with his tousled gray hair and hollow-cheeked look, the same colors melted into a veiled unity. James was dressed up ready to go. Peter, the campaigner, had been there.

On a night table beside James two candles flickered. A crucifix rested between them. In one corner of the room there was a chest of drawers. “Should have had it removed before we started,” Peter thought. The chest, originally left there in order to hold a tape recorder, had become quite a nuisance. Probably would continue to be until the whole business was finished, Peter thought. But he knew better than to fiddle with any object in the room, once the exorcism had begun.

It was a Monday, 8:15 P.M., the seventeenth hour into Peter’s third exorcism in thirty years. It was also his last exorcism, although he could not know that. Peter felt sure that he had arrived at the Breakpoint in the rite.

In the few seconds it took him to cross from the window to her bed, Marianne’s face had been contorting into a mass of crisscrossing lines. Her mouth twisted further and further in an S-shape. The neck was taut, showing every vein and artery; and her Adam’s apple looked like a knot in a rope.

The ex-policeman and her uncle moved to hold her. But her voice threw them back momentarily like a whiplash:

“You dried-up fuckers! You’ve messed with each other’s wives. And with your own peenies into the bargain. Keep your horny paws off me.”

“Hold her down!” Peter spoke peremptorily. Four pairs of hands clamped on her. “Jesus have mercy on my baby,” muttered her father. The ex-policeman’s eyes bulged.

“YOU!” Marianne screamed, as she lay pinned flat on the bed, her eyes open and blazing with anger, “YOU! Peter the Eater. Eat my flesh, said she. Suck my blood, said she. And you did! Peter the Eater! You’ll come with us, you freak. You’ll lick my arse and like it, Peeeeeeeeetrrrrrr,” and her voice sank through the “rrrr” to an animal gurgle.

Something started to ache in Peter’s brain. He missed a breath, panicked because he could not draw it, stopped and waited, swaying on his feet. Then he exhaled gratefully. To the younger priest he looked frail and vulnerable. Father James handed Peter his prayer book, and they both turned to face Marianne.

PETER

Almost a year later, in 1966, on the day Peter was buried in Calvary Cemetery, his younger colleague, Father James, chatted with me after the funeral service. “It doesn’t matter what the doctor said” (the official report gave coronary thrombosis as cause of death), “he was gone, really gone, after that last to-do. Just a matter of time. Mind you, it wasn’t that he wasn’t brave and devoted. He was a real man of God before and after the whole thing. But it took that last exorcism to make him realize that life knocks the stuffing out of any decent man.” Peter had apparently never emerged from a gentle reverie after the exorcism of Marianne; and he always spoke as if he were talking for the benefit of someone else present. It was as exasperating as listening to one side of a telephone conversation.

“He was never the same again,” said James. “Some part of him passed into the Great Beyond during the final Clash, as you call it.” Then, after a pause and musingly, almost to himself: “Can you beat that? He had to be born in Lisdoonvarna* sixty-two years ago, be reared beside Killarney, and come all the way over here three times—just to find out the third time where he was supposed to die; and how, and when. Makes you think what life’s all about. You never know how it’s going to end. Peter did not become an American citizen, even. All that travel. Just to die as the Lord had decided.”

Peter was one of seven children, all boys. His father moved from County Clare to Listowel, County Kerry, where he prospered as a wine merchant. The family lived in a large two-story house overlooking the river Feale. They were financially comfortable and respected. Their Roman Catholicism was that brand of muscular Christianity which the Irish out of all Western nations had originated as their contribution to religion.

Peter spent his youth in the comparative peace of “the old British days” before the Irish Republican Brotherhood (parent of the IRA), the Irish Volunteers, and the 1916 Rebellion started modern Ireland off on the stormy course of fighting for the “terrible beauty” that lured Patrick Pearse, James Connolly, Eamonn De Valera, and the other leaders into the deathtrap of bloodletting, where, 50 years later, in Peter’s declining years, blood was still being shed.

School filled three-quarters of the year for Peter. Summers were spent at Beal Strand, at Ballybunion seaside, or harvesting on his grandfather’s farm at Newtownsands.

One such summer, his sixteenth, Peter had his only brush with sex. He had lain for hours among the sand dunes of Beal Strand with Mae, a girl from Listowel whom he had known for about three years. That day, their families had gone to the Listowel races.

Innocent flirting developed into simple love play and finally into a fervid exchange of kisses and caresses, until they both lay naked and awesomely happy beneath the early-evening stars, the warmth undulating and glowing sweetly through their bodies as they huddled close together. Afterward, Mae playfully nicknamed him “Peter the Eater.” To calm his fear she added: “Don’t worry. No one will know how you made love to me. Only me.”

For about a year afterward, he was interested in girls and particularly in Mae. Then early in his eighteenth year, he began to think of the priesthood. By the time he finished schooling, his mind was made up. Peter had told me once: “When we said goodbye, that summer of 1922, Mae teased me: ‘If you ever leave the seminary and don’t marry me, I’ll tell everyone your nickname.’ She never told a human soul. But, of course, they knew.” Peter’s sole but real enemies were the shadowy dwellers of “the Kingdom” whom he vaguely called “they.” He gave me a characteristic look and stared away over my head. Mae had died in 1929 of a ruptured appendix.

Peter started his studies at Killarney Seminary and finished them at Numgret with the Jesuits. He was no brilliant scholar, but got very good grades in Canon Law and Hebrew, which he pronounced with an Irish brogue (“My grandfather was from one of the Lost Tribes”), acquired a reputation for good, sound judgment in moral dilemmas, and was renowned locally because with one deft kick of a football he could knock the pipe out of a smoker’s mouth at 30 yards and not even graze the man’s face.

Ordained priest at twenty-five, he worked for six years in Kerry. Then he did a first stint in a New York parish for three years. He was present twice at exorcisms as an assistant. On a third occasion, when he was present merely as an extra help, he had to take over from the exorcist, an older man, who collapsed and died of a heart attack during the rite.

Two weeks before he sailed home to Ireland for his first holiday in three years, the authorities assigned him his first exorcism. “You’re young, Father. I wish you’d had more experience,” was the way he recalled the bishop’s instructions, “but the Old Fella won’t have much on you or over you. So go to it.”

It had lasted 13 hours (“In Hoboken, of all places,” he used to say whimsically), and had left him dazed and ill at ease. He never forgot the statement of murderous intent hurled at him by the man he had exorcised. Through foaming spittle and clenched teeth and the smell of a body unwashed for two years prior, the man had snarled: “You destroy the Kingdom in me, you shit-faced alien Irish pig. And you think you’re escaping. Don’t worry. You’ll be back for more. And more. Your kind always come back for more. And we will scorch the soul in you. Scorch it. You’ll smell. Just like us! Third strike and you’re out! Pig! Remember us!” Peter remembered.

But a two-week vacation in County Clare restored him to his energy and verve. “God! The scones running with salty butter, and the hot tea, and the Limerick bacon, and the soft rain, and the peace of it all! ’Twas great.”

Most of Peter’s wounds were not inflicted by the harsh realities of the world around him; but, deep within him, they opened as his way of responding to the evil he sometimes sensed in daily life.

Those who still remembered him in 1972 agreed that Peter had been neither genius nor saint. Black-haired, blue-eyed, raw-boned in appearance, he was a man of little imagination, deep loyalties, loud laughter, gargantuan appetite for bacon and potatoes, an iron constitution, an inability to hate or bear a grudge, and in a state of constant difference of opinion with his bishop (a tiny old man familiarly called “Packy” by his priests). Peter was somewhat lazy, harmlessly vain about his 6’ 2” height, and a lifelong addict of Edgar Wallace detective stories.

“He had this distinct quality,” remarked one of his friends. “You felt he had a huge spirit laced with cast-iron common sense and untouched by any pettiness.”

“If he met the Devil at the top of the stairs one morning and saw Jesus Christ standing at the bottom,” added another, “he wouldn’t turn his back on the one in his hurry to get down to the other. He’d back down. Just to be sure.”

In normal circumstances, Peter would have stayed on permanently in Ireland after his vacation of scones and soft rain. He would have worked in parishes for some years, then acquired a parish of his own. But there was something else tugging at his heart and something else written in his stars. When he left for New York at the outbreak of the Korean War in order to replace a chaplain who had been called up, he recalled the exorcism in Hoboken. “Third strike and you’re out! Pig! Remember!”

He remarked jokingly to a worried friend who knew the whole story: “’Tis not the third time yet!”

In January 1952, he was asked to do his second exorcism. His effectiveness in the first exorcism and the resilient way he had taken it recommended him to the authorities. The exorcism took place in Jersey City. And, in spite of its length (the better part of three days and three nights), it took very little out of him physically or mentally. Spiritually, it had some peculiar significance for him.

“It was a sort of warmer-upper for the 1965 outing,” he told me in 1966. “The ceremony lasted too long for my liking, was hammer and tongs all the way, almost beat us. But there was no great strain inside here [pointing to his chest].” And he added with a significance that eluded me then: “Jesus had a forerunner in the Baptist. I suppose darkness has its own.”

Looking back on his role as exorcist today, it is clear to me that the first two exorcisms prepared him for the third and last one. They were three rounds with the same enemy.

The exorcee that January was a sixteen-year-old boy of Hispanic origin who had been treated for epilepsy over a period of years, only to be finally declared nonepileptic and physically sound as a bell by a team of doctors from Columbia Presbyterian Hospital. Nevertheless, on the boy’s return home, all the dreadful disturbances started all over again in a much more emphasized way, so the parents turned to their priest.

“They tell me you’ve a…eh…a sort of a way with the Devil, Father,” said the wheezy, red-faced monsignor, grinning awkwardly as he gave the necessary permissions and instructions to Peter. Then, stirring in his chair, he added grimly as a bad Catholic joke: “But don’t bring him back here to the Chancery with you. Get rid of him or it or her or whatever the devil it is. We have enough of all that on our backs here already.”

It had gone well. The boy became Peter’s devoted friend. Later he went to Vietnam and died in an ambush late one night outside Saigon. His commanding officer wrote, enclosing an envelope with Peter’s name on it which the dead man had left behind. It contained a piece of bloodstained linen and a short note. Over a decade previously, just before his release from possession, in a final paroxysm of revolt and appeal, he had clawed at Peter’s wrist, and Peter’s blood had fallen on his shirt sleeve. “I kept this as a sign of my salvation, Father,” the note said. “Pray for me. I will remember you, when I am with Jesus.”

Peter was then forty-eight years old and in his prime as a priest. Yet in himself, he suffered from a growing sense of inadequacy and worthlessness. He felt that, in comparison with many of his colleagues who had attained degrees, qualifications, high offices, and acknowledged expertise, he had very little to show by way of achievement. “I have no riches inside me,” he wrote to a brother of his, “just black poverty. Sometimes it darkens my soul.” When his turn for a parish of his own came around, he was passed over. (Packy was dead already; but, some said, the dead bishop had made sure in his records that Peter would be passed over.)

Peter, in fact, was a maverick. The normal priest found him inferior in social graces but superior in judgment, lacking in ecclesiastical know-how and ambition but very content with his work. Sometimes his protestations of being “poor inside,” of having “no excellent talents” sounded hollow when matched with his stubborn and opinionated attitudes. Anyway, the normal bishop would take one look into his direct gaze and decide that his own authority was somehow at stake. For Peter’s stare was not insolent, but yet unwavering; it acknowledged the demands of worth but was devoid of any subservience. It said: “I respect you for what you represent. What you are is something else.” Such a man was unsettling for the absolutist mind and threatening for the authoritarian bent of most ecclesiastics.

Beyond the occasional funny remark, such as “The higher they go, the blacker their bottoms look,” Peter gave no outward impression of discontent or anxiety. A lack of self-confidence saved him from revolt or disgust. And he bore it all lightly. “Well, Father Peter,” one bishop joshed him...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Preface to the New Edition: Possession and Exorcism in America in the 1990s

- The Fate of an Exorcist

- The Cases

- Manual of Possession

- The End of an Exorcist

- Appendix I: The Roman Ritual of Exorcism

- Appendix II: Prayers Commonly Used in Exorcisms

- Searchable Terms

- About Hostage to the Devil

- About Malachi Martin

- About the Author

- Other Books by Malachi Martin

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Hostage to the Devil by Malachi Martin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teología y religión & Historia y teoría en psicología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.