- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Today more than ever, international headlines are dominated by reports from the many dictatorships that still exist around the world. Led by royal families, military juntas, or single political parties, despotic regimes persist in repressing and brutalizing their citizens.

In Tyrants, New York Times bestselling author David Wallechinsky offers in-depth portraits of twenty dictators and their governments. Wallechinsky probes their often mysterious backgrounds, exposes their crimes, and reveals details about their strange personalities and quirks. Tyrants also reveals the extent to which foreign corporations and governments support these leaders. Timely and provocative, Tyrants will awaken readers to the criminal regimes of the present day, and pose challenging questions about America's role in curbing (or promoting) their power in the future. David Wallechinsky is the bestselling co-author of The Book of Lists and The People's Almanac, and the author of The Complete Book of the Summer Olympics and The Complete Book of the Winter Olympics. A contributing editor to Parade magazine, he divides his time between Santa Monica, CA, and Provence.Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tyrants by David Wallechinsky in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

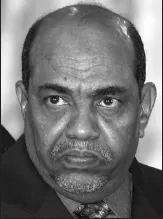

(George Mulala/Reuters/Corbis)

1.

OMAR AL-BASHIR—SUDAN

THE NATION—Sudan, by size, is the largest nation in Africa and the tenth-largest nation in the world. It shares borders with nine different nations; only China, Russia, and Brazil have more neighbors than Sudan. Since achieving independence from the British in 1956, the nation has experienced only ten years of peace. The rest of the time it has been plagued by a series of overlapping civil wars. Since 1983, an estimated two million Sudanese have died of war-related causes, while five million have been forced from their homes. Since 1993, Sudan has been the world’s leading debtor to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Sudan’s population of about 38 million is deeply divided ethnically and religiously. Although 52 percent of the population is black, the nation has always been ruled by the minority, who are Arabs. Seventy percent of Sudanese are Sunni Muslims, 25 percent follow traditional religions—referred to as animism or primitive religion by Westerners—and 5 percent are Christians, mostly Catholic. A census taken at the time of independence identified 50 ethnic groups, 570 distinct peoples, and the use of 114 languages, although more than half the population speaks Arabic.

SLAVERY—In recent years, the media have devoted a good deal of attention to the killings in Darfur in western Sudan. One of the most disturbing aspects of this tragedy is that the exploitation of black people by Arabs in the Sudan has been going on for more than 1,400 years. The word “Sudani” in Arabic means “black.” This term, along with the words “Nuba” and “Nubia,” which relate to one of the areas in southern Sudan populated by black Africans, have all entered colloquial Arabic with the meaning of “slave.”

Christian missionaries arrived in the region in the 6th century from Constantinople and Islamic missionaries in the seventh century. As early as 652 a treaty was signed in which Muslim Egypt would provide goods to Christian Nubia in exchange for Nubian slaves. Slave raids in southern Sudan continued almost without a break for the next 1,300 years, no matter who ruled the region—Egyptians, Turks, or local sultans. Muhammad Ali, the Albanian-born ruler of Egypt, invaded Sudan in 1821, leading to sixty years of Turco-Egyptian rule. During this period, which saw the introduction of domestic slavery and the development of slave soldiers, an average of 30,000 southerners a year were seized in slave raids.

Muhammad Ali also founded the city of Khartoum at the confluence of the White Nile and the Blue Nile. In 1885, the forces of Mohammad Ahmed al-Mahdi (Mohammad the Messiah) captured Khartoum and overthrew the Turco-Egyptian regime. Al-Mahdi died the same year and was replaced by Abdullahi ibn Muhammad, known as the Khalifa. The Mahdists expanded the practice of slavery, driving millions from their homes. They also set an unfortunate precedent by demanding that citizens take a personal, religious oath of loyalty to Mahdi and the Khalifa and condemning nonfollowers, even fellow Muslims, as “unbelievers.” When British and Egyptian troops invaded Sudan, these rejected Muslims were glad to help overthrow the Mahdists.

The Anglo-Egyptian forces, led by General Horatio Herbert Kitchener, defeated the Mahdist army at the Battle of Omdurman on September 2, 1898, and the Sudan became a possession of the king of England. The British abolished slavery, outraging the Arabs in northern Sudan, who considered the practice not a question of human rights, but a cultural tradition that was being disrupted by foreign invaders. The British also halted the spread of Islam to new areas and assigned separate zones to Catholic and Protestant missionaries, most of whom arrived from Austria, Italy, and the United States. The Americans distinguished themselves by their obsession with clothing the natives.

The Mahdists had never established control over southern Sudan, and it took the British a long time to deal with it themselves. As part of their pacification campaign, the British-led army occasionally burned down villages in the south, just as the Egyptians and Mahdists had done, and they were even known to seize cattle just to prove they had the power to do so. In 1930, the British declared a Southern Policy that stated that the region was African rather than Arab, but because there were few hereditary rulers in the south, it remained difficult for the British to establish consistent authority. In the north, meanwhile, tensions developed between the British and their junior partners, the Egyptians. In the 1920s, the British expelled Egyptian soldiers and administrators and, to counter the growing influence of Egypt in Sudan, they brought back the posthumously born son of the anti-Egyptian Mahdi. The grand qadi (judge) of the religious courts was always an Egyptian, but the British ended this monopoly in 1947. After World War II, the British came up with a novel tactic for stemming the threat of Egyptian power in Sudan: they proposed that the Sudan be granted independence, even though few Sudanese themselves had demanded it. When formal negotiations for independence began in 1952, Egypt was included, but the black Sudanese in the south were not.

Sudan’s first election, held in 1953, was generally fair, although women were not allowed to vote. (Women’s suffrage finally occurred in 1967.) The National Unionist Party, which advocated political union with Egypt, emerged as the largest single party, but it failed to gain a majority of the votes, and a coalition of anti-unionist parties turned union into a dead issue. The new, pre-independence government also showed no interest in sharing power with the black Sudanese and appointed northerners to all leadership positions in the south. This continuation of the Arab view that the southern tribes were not fit to be partners led to a shocking incident in the summer of 1955. When the northern government ordered southern soldiers in the state of Equatoria to transfer north, they refused. In what became known as the Torit Mutiny, the soldiers went on a rampage against the administrators from the north, killing 450 people, including women and children. The northern authorities were outraged, but not enough to ask themselves what could be done to mitigate southern anger.

Great Britain practically forced Sudan to declare independence on January 1, 1956, before a constitution had been written and before the achievement of anything that could be even remotely considered a national consensus. The southern Sudanese were understandably wary of the northerners’ intentions toward them. Southern leaders pushed for a federal system that would allow them some regional control, but the northerners took the position that giving the south any power at all would lead eventually to secession or that it would, at the very least, threaten the master–servant relationship that they considered part of their “traditional culture.”

Less than two months after independence, an incident took place that would serve as an awful harbinger of the violence that has cursed Sudan ever since. Police in Kosti locked 281 striking tenant farmers in a room. By morning, 192 of them were dead.

The first post-independence election, in 1958, exposed Sudan’s deep divisions, as the ruling alliance fractured and the southerners established their own party. A nationwide strike, led by labor unions, the tenant farmers’ union, students, and the Communist Party, brought the country to a standstill. On November 17, 1958, the military, led by General Ibrahim Abbud, seized power and declared a state of emergency. This came as a relief to both the Western powers and the USSR, who found a democratic Sudan difficult to deal with. The new government set out to Arabize and Islamicize the south, using Arab traders and Muslim missionaries as a vanguard and then sending in the army to burn villages and to arrest and torture civilians. They also ordered that the day of Sabbath be changed from Sunday to Friday.

THE FIRST CIVIL WAR—In 1962, southern Sudanese living in exile, including students and ex-mutineers, formed the Sudan African Nationalist Union (SANU), which eventually included a guerrilla wing known as Anyanya, which is a type of poison. SANU appealed to the West for support, but the Europeans and Americans were not interested. SANU also received little help from fellow Africans because the Organization of African Unity had pledged to retain all colonial boundaries and SANU’S call for “self-determination” was judged counter to this pledge. Anyanya managed to acquire weapons by hijacking Sudanese government convoys that were transporting arms to pro-Arab rebels in the Congo. Fighting between the southern rebel forces and Sudanese government forces began slowly. The first major rebel attacks started in September 1963. Both sides were ruthless in their tactics. However, along the way, Anyanya discovered the Maoist strategy that guerrillas can survive by befriending the locals and becoming “fish in a sea of people.”

Meanwhile, back in Khartoum, things were not going well for General Abboud, who was not the most competent of leaders. Student protests, street demonstrations, and a general strike finally led to a popular uprising that overthrew Abboud in October 1964. A transitional government was formed by Communists and unions of tenants, workers, and farmers, which allowed women to obtain some political rights. Six months later an election was held, but only in the north. The newly elected government made clear its intentions in the south by approving the first large-scale massacres of civilians. When war broke out between Israel and its Arab neighbors, Sudan supported the Arabs, broke relations with the United States, and turned to the Soviet Union, which led to a drastic decline in foreign aid. As the war in the south grew to eat up one-third of the national budget, Sudan’s foreign debt doubled between 1964 and 1969, putting great pressure on the northern poor.

Another election was held in 1968, but few in the south were able to vote. By this time the rebel movement had grown large enough to develop bickering factions. They did find it easier to acquire weapons and training because enemies of the Sudanese government, such as Israel, Ethiopia, and Uganda, were happy to supply the rebels.

In March 1972, the government and the rebels signed a settlement, the Addis Ababa Agreement, that ended the civil war. This was the first negotiated settlement in postcolonial Africa, but eventually the southerners would come to regret it and consider it a failure. The agreement provided for the gradual absorption of the Anyanya guerrillas into the national army, but northern troops did not leave the south and many guerrillas chose to go into exile in Ethiopia. Economically and politically, the promises of the Addis Ababa Agreement would turn out to be illusory.

NIMEIRI AND THE INTERLUDE OF PEACE—On May 24, 1969, Colonel Jaafar Nimeiri overthrew the elected government of Sudan by bringing together the military and the Communist and Socialist parties. Nimeiri would prove to be a completely self-serving politician who would make or break an alliance with any group, so long as it helped him stay in power. For example, by 1970 he had booted out of office all of the Communist ministers who had helped him with his coup d’état. Nimeiri civilianized himself by staging a phony election in September 1971, in which he won 99 percent of the votes. Not surprisingly, the traditional political parties turned against him, so he countered their potential strength by reaching out to the southern rebels and negotiating the Addis Ababa Agreement. Nimeiri then shoved through a new constitution in April 1973 that created a one-party state. That party was Nimeiri’s Sudan Socialist Union. He put himself in command of the armed forces and made the judiciary completely answerable to the president (Nimeiri). He also gave the security services broad powers of search and arrest and set up a large network of informers.

Another group of growing influence whom Nimeiri chose to co-opt was the Islamists; religious radicals led by Hassan al-Turabi, a man who would rise to great power after Omar al-Bashir took over as dictator of Sudan. To appease the Islamists, Nimeiri released Turabi from the prison where he had been languishing for seven years. Nimeiri began incorporating the Islamist agenda into his own. He supported Arab Iraq in its war against non-Arab Iran and, in September 1983, he imposed Shari’a, or Islamic, law on Sudan. He also sold out the southern rebels, supporting the 1978 Camp David Accords so that Israel would stop supplying the southern guerrillas. In 1983 he abolished the system of regional councils that had provided the southern Sudanese a modicum of power.

Nimeiri made friends with the U.S. government, which viewed him as a counterweight to pro-Soviet regimes in Ethiopia and Libya. Fully aware that U.S. president Ronald Reagan would support any government that was “anti-Communist,” Nimeiri convinced the Reagan administration that the southern rebel forces were Communists. This earned him $1.4 billion in aid, including U.S.-made aircraft that he used to attack southern troops. In exchange, Reagan was able to use the “defense of Sudan” as his excuse for bombing Libya in 1986. Vice President George H.W. Bush visited Nimeiri in Khartoum in 1985 while accompanied, rather bizarrely, by American televangelists Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell. It was during a return trip to the United States in April 1985 that, after sixteen years in power, Nimeiri’s luck finally ran out. After a government-imposed rise in food prices, a popular uprising led to a coup that overthrew him. It was little realized at the time, but the most horrible aspect of Nimeiri’s legacy was his creation of the practice of supplying tribal militias to fight as surrogates so that he could deny that the Sudanese army was fighting antigovernment forces. The current Sudanese government is still employing the same tactic in Darfur.

One year after the 1985 coup, Sudan held another election, although only half of the south took part. Sadiq al-Mahdi, the leader of the UMMA party, emerged as the prime minister. Sadiq committed Sudan to becoming an Islamic state. Upon his election in April 1986, he put it bluntly: “Non-Muslims can ask us to protect their rights—and we will do that—but that’s all they can ask. We wish to establish Islam as the source of law in Sudan because Sudan has a Muslim majority.” This was an unusually bold, or one might say, rash statement, considering that the non-Muslim rebel groups in the south were dramatically gaining strength. In fact, the civil war, which had recommenced, was turning horrifically ugly.

The largest of the rebel groups was the SPLA, led by John Garang, who had earned a doctorate in agricultural economics at Iowa State University and had also attended a U.S. Army infantry officer’s course at Fort Benning, Georgia. The SPLA represented the largest of the southern ethnic groups, the Dinka. In 1985 and 1986, the SPLA, desperate for supplies, staged a series of vicious attacks against civilians. But then the SPLA learned a miraculous lesson: if you treat civilians well, they might actually support you. As obvious as this may seem, it is a fact that continues to escape the Sudanese government. In 1987, the SPLA changed tactics. Instead of attacking villages and seizing food and other goods, it imposed a food tax that, once paid, protected villagers from seizures. Since the Sudanese army continued to attack people’s homes, the popularity of the SPLA grew and, in 1988, for the first time, it was no longer viewed by other tribes as a purely Dinka army.

The government-supported Murahalin militia, on the other hand, was engaging in grotesque tactics, burning to the ground Dinka villages and killing civilians. It regularly abducted Dinka and sent them north to be kept in slavery or traded, while children, who had been raised non-Muslim, were forced to attend Islamic schools and adopt new names. Captured women were forced to endure genital mutilation.

One particularly infamous atrocity, the Ed-Da’ein Massacre, was carried out on March 28, 1987. Two thousand Dinka villagers, fearing an attack by a Muslim tribe, the Baggara, asked for police protection. The police told them to take shelter in nearby railway freight cars. That night, the police stood by and watched as the Baggara set fire to the railway cars, killing at least a thousand people.

In 1987, the SPLA scored a stunning defeat of the Murahalin and the Sudanese army, which responded to the humiliation by attacking unarmed Dinka refugees in Southern Darfur. Sadiq al-Mahdi had never had the full support of the army, and he further alienated them with his dependency on tribal militias. As the military situation deteriorated and the SPLA took the fighting north to areas previously controlled by the government, the army demanded that Sadiq meet with John Garang and try to negotiate a ceasefire. Sadiq finally agreed. This decision infuriated one of the parties in his ruling coalition, Hassan al-Turabi’s National Islamic Front (NIF), which withdrew from the coalition. On June 30, 1989, before Sadiq could meet with Garang, a group of Muslim army officers, led by Brigadier General Omar al-Bashir and supported by the NIF, staged a coup. The coup leaders called themselves the National Movement for Correcting the Situation.

THE MAN—Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir was born in 1944 in Hoshe Bannaga, 100 kilometers northeast of Khartoum. A member of the Ja’aliya tribe, he came from a rural working-class family and attended Ahlia Middle School in the town of Shendi. Bashir’s family moved to Khartoum, where he attended secondary school and worked in a garage. Bashir found his niche in the military world. Admitted to a military academy for training as a pilot, he graduated from Sudan Military College at the age of twenty-two and then earned two master’s degrees in military science, one from the Sudanese College of Commanders and the second in Malaysia. By 1973, he was serving as a paratrooper in the Arab-Israeli War. Bashir was jovial and well-liked, and his natural affinity with fellow officers would serve him well in the decades to come. He was particularly friendly with those officers who were sympathetic to the National Islamic Front. In late 1985, military intelligence identified Bashir as a potential leader of an NIF coup and he was transferred to remote garrisons, including Muglad, which was used as a base for operations against rebel forces in the south and the Nuba Mountains. As a sign of his solidarity with his own forces, Bashir would choose as his second wife the widow of a fellow officer killed in the fighting.

In 1988, Bashir was promoted to brigadier and put in command o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Map

- The World of Dictators

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Appendix: Overthrown Modern-Day Dictators and Their Fate

- Suggested Reading List

- Acknowledgments

- Searchable Terms

- About the Author

- Other Books by David Wallechinsky

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher