eBook - ePub

Growing Up Black

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

IV

The Twentieth Century: 1951 to the Present-

After We Have Overcome

THE TIME BETWEEN THE EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION AND BROWN VS. the Board of Education was not quite a hundred years. From 1954 to 1984 when Jesse Jackson ran for president was thirty short years. In historic terms, the change in the status of black Americans is revolutionary, but in social terms, the change is slow and often painful.

These selections tell us about children who knew the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., the march to Selma, the march on Washington, the summer of love, Malcolm X, Vietnam War protests, Kent State, Huey Newton, “Black Power,” naturals, and integrated schools. The messages of the time were confusing and conflicting: cultural integration vs. cultural separatism, acceptance vs. fear, nonviolence vs. armed revolution. This section captures that confusion and pain.

From The Long Shadow of Little Rock

as told to Daisy Bates

ELIZABETH ECKFORD

(1942–)

Elizabeth Eckford was one of the black pupils to whom Little Rock’s Central High School reluctantly opened its doors in the now famous integration showdown of 1957. The children had originally planned to enter the school in a group, but with racial tensions beyond the danger level, plans were suddenly changed. Eckford somehow was never notified of this change. Thus it came to pass that she was left completely alone to face the full fury of the rabid mob that had gathered outside the school. The experience left her near hysteria and it was a long time before she was able to recount the episode. The following selection is her account of the near-tragic incident as told to Daisy Bates.

Eckford graduated from Central High School in 1960. She attended Knox University in Galesburg, Illinois, for one year, then transferred to Central State College in Wilberforce, Ohio.

“The day before we were to go in, we met Superintendent Blossom at the school board office. He told us what the mob might say and do but he never told us we wouldn’t have any protection. He told our parents not to come because he wouldn’t be able to protect the children if they did.

“That night I was so excited I couldn’t sleep. The next morning I was about the first one up. While I was pressing my black and white dress—I had made it to wear on the first day of school—my little brother turned on the TV set. They started telling about a large crowd gathered at the school. The man on TV said he wondered if we were going to show up that morning. Mother called from the kitchen, where she was fixing breakfast. ‘Turn that TV off!’ She was so upset and worried. I wanted to comfort her, so I said, ‘Mother, don’t worry.’

“Dad was walking back and forth, from room to room, with a sad expression. He was chewing on his pipe and he had a cigar in his hand, but he didn’t light either one. It would have been funny, only he was nervous.

“Before I left home Mother called us into the livingroom. She said we should have a word of prayer. Then I caught the bus and got off a block from the school. I saw a large crowd of people standing across the street from the soldiers guarding Central. As I walked on, the crowd suddenly got very quiet. Superintendent Blossom had told us to enter by the front door. I looked at all the people and thought, ‘Maybe I will be safer if I walk down the block to the front entrance behind the guards.’

“At the corner I tried to pass through the long line of guards around the school so as to enter the grounds behind them. One of the guards pointed across the street. So I pointed in the same direction and asked whether he meant for me to cross the street and walk down. He nodded ‘yes.’ So I walked across the street conscious of the crowd that stood there, but they moved away from me.

“For a moment all I could hear was the shuffling of their feet. Then someone shouted, ‘Here she comes, get ready!’ I moved away from the crowd on the sidewalk and into the street. If the mob came at me I could then cross back over so the guards could protect me.

“The crowd moved in closer and then began to follow me, calling me names. I still wasn’t afraid. Just a little bit nervous. Then my knees started to shake all of a sudden and I wondered whether I could make it to the center entrance a block away. It was the longest block I ever walked in my whole life.

“Even so, I still wasn’t too scared because all the time I kept thinking that the guards would protect me.

“When I got right in front of the school, I went up to a guard again. But this time he just looked straight ahead and didn’t move to let me pass him. I didn’t know what to do. Then I looked and saw that the path leading to the front entrance was a little further ahead. So I walked until I was right in front of the path to the front door.

“I stood looking at the school—it looked so big! Just then the guards let some white students go through.

“The crowd was quiet. I guess they were waiting to see what was going to happen. When I was able to steady my knees, I walked up to the guard who had let the white students in. He too didn’t move. When I tried to squeeze past him, he raised his bayonet and then the other guards closed in and they raised their bayonets.

“They glared at me with a mean look and I was very frightened and didn’t know what to do. I turned around and the crowd came toward me.

“They moved closer and closer. Somebody started yelling, ‘Lynch her! Lynch her!’

“I tried to see a friendly face somewhere in the mob—someone who maybe would help. I looked into the face of an old woman and it seemed a kind face, but when I looked at her again, she spat on me.

“They came closer, shouting, ‘No nigger bitch is going to get in our school. Get out of here!’

“I turned back to the guards, but their faces told me I wouldn’t get help from them. Then I looked down the block and saw a bench at the bus stop. I thought, ‘If I can only get there I will be safe.’ I don’t know why the bench seemed a safe place to me, but I started walking toward it. I tried to close my mind to what they were shouting, and kept saying to myself, ‘If I can only make it to that bench I will be safe.’

“When I finally got there, I don’t think I could have gone another step. I sat down and the mob crowded up and began shouting all over again. Someone hollered, ‘Drag her over to this tree! Let’s take care of this nigger.’ Just then a white man sat down beside me, put his arm around me and patted my shoulder. He raised my chin and said, ‘Don’t let them see you cry.’

“Then, a white lady—she was very nice—she came over to me on the bench. She spoke to me but I don’t remember now what she said. She put me on the bus and sat next to me. She asked me my name and tried to talk to me but I don’t think I answered. I can’t remember much about the bus ride, but the next thing I remember I was standing in front of the School for the Blind, where Mother works.

“I thought, ‘Maybe she isn’t here. But she has to be here!’ So I ran upstairs, and I think some teachers tried to talk to me, but I kept running until I reached Mother’s classroom.

“Mother was standing at the window with her head bowed, but she must have sensed I was there because she turned around. She looked as if she had been crying, and I wanted to tell her I was all right. But I couldn’t speak. She put her arms around me and I cried.”

From Every Good-bye Ain’t Gone

ITABARI NJERI

(1955– )

Descending from a Harvard-educated, Marxist historian and a nurse of West Indian ancestry, Itabari Njeri was bound to have an interesting childhood. She grew up in Brooklyn and Harlem surrounded by family, a colorful family with tragedy and history. One of her aunts was a gangster’s moll in Harlem. Her great-great-great grandfather was a pirate. Her grandfather was killed under suspicious circumstances in an automobile wreck with a white driver in Georgia.

If her childhood was colorful, it was sometimes unhappy. Her father and mother were separated but occasionally reunited. Her father was aloof and bitter, sometimes abusive, and often drunk. Barred from prestigious teaching positions because of his leftist political leanings, he taught at a Jersey City high school. While she hated and was intimidated by her father, his brilliance attracted her. At the same time, she resented her mother’s acceptance of his abuse.

Njeri, a graduate of Boston University and the Columbia University School of Journalism, is an award-winning journalist on staff with the Los Angeles Times. She captured the characters of her life in this well-received autobiography in 1990, and the following piece is excerpted from it.

By the time I’d hit the kitchen she was in high gear: burning sugar, dicing currants, pouring out the extra-proof rum—sipping the extra-proof rum. Be aware: The cake my grandmother made bore no resemblance to the pale, dry, maraschino cherry-pocked fruitcakes most Americans know. This was a traditional West Indian fruitcake and an exquisite variation of it at that.

As a little girl and since, I’ve been to more than a few West Indian celebrations where the host served a dry, crumbling, impotent confection and dared to call it fruitcake. Only good manners prevented me from going spittooey on the floor, like some animated cartoon character. Instead, the members of my family would take a bite, control themselves, then exchange smug glances: Nothing like Ruby’s, we’d agree telepathically.

What Ruby Hyacinth Duncombe Lord created was the culmination of a months-long ritual. The raisins, the prunes, the currants and the citron were soaked in a half gallon of port wine and a pint of rum for three months in a cool, dark place. Even after the cake was baked, liquor was poured on it regularly to preserve it and keep it moist for months. When you finally bit into a piece, the raisins spat back rum.

On the special occasions the cake was served—holidays, birthdays, weddings—I was often outfitted in some party frock my mother, or one of the West Indian seamstresses on the block, had made. Sometimes a bit of hem or a snap required last-minute adjustments. My grandmother would run for the sewing tin and make the alterations with me still in the dress. Her mending done, the needle and thread poised in her upheld hand, she grabbed my wrist.

“Grandmaaaaaah,” I squealed extravagantly. She sucked her teeth at my absurd resistance.

“Stop that noise before I knock you into oblivion. Are you insane? Do you actually wish to walk around in your burial shroud?” she asked incredulously. And then she pricked the inside of my wrist, breaking the spell of death that fell when cloth was sewn on a living soul.

I do not know the origins of the practice. Perhaps it was African, as were many things, I later learned, we did and said without realizing it. But such things were not unusual in that place, at that time.

I lived in a country one Brooklyn block long. It was an insular world of mostly West Indians who dwelled in both stately and sagging brownstones, and the occasional wood house that dotted the street.

Scattered among them were Afro-American immigrants from the South. Most mornings, the elder members of these extended families could be seen sweeping and hosing down the sidewalk in front of their row or wood-frame homes. Many of them had come north during the first great migration of blacks from the South around World War I. They were escaping the neoslavery of the post-Reconstruction period. At the same time, my maternal grandparents were sailing from the Caribbean to the United States, fleeing the social prison of British colonialism.

Many of these early Afro-British and Afro-American migrants had saved enough money to buy homes in this Clinton Hill enclave and the surrounding Fort Greene neighborhood in the 1940s when the area opened up to blacks.

Our landlady, and hairdresser, too—she operated a discreet salon on the ground floor of her 1860 Italianate row house—was from Barbados. For years, beginning with my mother, she rented the tree-shaded second floor of her home to members of my family before they bought houses of their own.

The block’s most recent arrivals seemed to live in the one tenement I recall on our street, a sturdy, pre-World War II structure whose communal corridors were as tidy as the foyers in the block’s private homes.

Like most immigrants, those on our street seemed to possess a drive, tenacity and pride that often set them apart from their countrymen. The social ravages of northern, urban life had yet to engulf the citizens of St. James Place. And the American century, a little past its midpoint, had not fully become what it is—vulgar and dangerous without respite.

As I prepared to leave this country each morning, boarding the bus to the Adelphi Academy nursery school, the old man hosing down the street would wave to me and say, “Be good now.” I do not remember his name, if I ever knew it. The people outside of my immediate family and their intimate circle of friends were of fleeting significance to me then. My first seven years on earth were dominated by island voices, resounding in narrow brownstone parlors where all that was wood was perfumed by lemon oil, and parquet floors glowed with the reflected light of chandeliers. It was here, in this world, that we cut the fruitcake.

“Love doll, come give Mariella a kiss,” my brother’s godmother called to me at one of these house parties, extending her arms and jiggling her bosom. She lived across the street and ran a boarding-house with a crew of mostly male students from Africa, the Middle East and the Caribbean. She was a good friend to my mother and a second grandmother to me. Ruby took her latter status as a personal insult, an offense compounded by Mariella’s looks (pretty), size (petite), manner (flirtatious), and age (ten to fifteen years off my grandmother’s).

Among her other sins, Mariella was from St. Croix, and her musical accent and speech tended to be as informal and coquettish as Ruby’s were imperial and bellicose.

“Y’know,” said Mariella, pointing to me, “I raise her since she was this high.” She bent down and measured about a foot off the floor. I was five and looked at her strangely. Even then I could figure out she’d probably had too much rum.

Ruby sucked her teeth disgustedly at Mariella’s familial claims, and my mother shot her a don’t-start-anything glance. Later, I’d hear my grandmother mutter, “Old gypsy pussy,” and label anything Mariella said “Anansi story anyway.”

“Gypsy pussy” went right over my head at the time, and it took years of repeated hearings—my grandmother sticking the label on any woman she considered flighty—before its meaning dawned on me.

As for “Anansi story,” I always thought she was talking about Nancy, some lady I’d never met. I didn’t know Anansi was the famed character of West African folklore, the spider who spun tales, his stories still told by the descendants of Africans who’d been brought to Jamaica.

With my two grandmothers in the room—the monarch an the gypsy—someone offered a toast. All raised their glasses but no one drank before a bit of liquor had been flicked with fingers to the floor. Ruby had already sprinkled spirits over the threshold when my mother moved into the apartment. Both gestures were a blessing and an ancestral offering.

While I did spend a lot of time with Mariella, who had two grandchildren my age, it was Ruby who was waiting for me after a hard half day at nursery school, then kindergarten, then the first and second grades. I’d tarry with my friends at the candy store before coming home, stocking up on red licorice, candy lipsticks and peppermint sticks. But Ruby and the whole block knew when I was approaching home; my voice came around corners before I did. I knew the Hit Parade by heart, a fact that did not always please my grandmother.

“You too forward,” she’d call down to me, her voice floating from our kitchen window above the limestone stairs where I’d planted myself with my bag of candy. Elbows on the stoop, legs dangling the length of three stone steps, I ignored my grandmother and kept singing.

“Oh the wayward wind is a restless wind, a restless wind that yearns to wander, and I was born—”

“What you know about a wayward wind, child? Come upstairs.” I loved the regal lilt of my grandmother’s accent, her tickled tone, despite the firmness of her call. But I pretended not to hear.

“Sixteen tons and whadiya get, another day older and deeper in—”

“Jill Stacey!” she bellowed, as I began “Blueberry Hill.”

Still stretched along the steps, I bent my long neck back, looked toward the sky and saw my grandmother’s head sticking out the kitchen window. “Grandma, you want me?” I asked, my scuffed saddle shoes still beating time against the pavement.

“I found my thrill… “

“Eh-eh,” Ruby uttered quickly, then sucked her teeth. “Yes, it’s you that I want. Come and don’t try me. Ya know I old ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- I Growing Up Black

- II The Nineteenth Century

- III The Twentieth Century: The First 50 Years

- IV The Twentieth Century: 1951 to the Present

- Acknowledgments

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

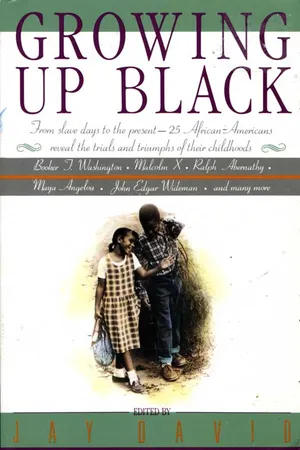

Yes, you can access Growing Up Black by Jay David in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.