At first the infant

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms

1. ALLUREMENTS

The Kingdom of Morocco has on its most widely used currency bill neither a camel nor a minaret nor a Touareg in desert blue, but the representation of the shell of a very large snail. The shell of this shore-living marine beast—a carnivore that uses its tongue to rasp holes in other creatures’ shells and sip out the goodness—is reddish brown, slender, and spiny, with a long spire and an earlike opening. It is in all ways rather beautiful, the kind of shell not to be idly thrown away by anyone lucky enough to find one.

Yet it was not the shell’s curvilinear elegance that many years ago persuaded directors of Morocco’s Central Bank in Rabat to place its image on the back of its 200-dirham bills. The reason for their choice, more befitting a currency note, had all to do with money and profit. For it was this curious sea creature that formed the basis of Morocco’s fortunes, long before Morocco was an organized nation.

The shell of Haustellum brandaris, or dye murex, on the 200-dirhan Moroccan banknote underscores its importance to the North African economy three thousand years ago. Phoenician traders harvested the shells from the Atlantic coast and from the mollusk’s hypobranchial gland extracted purple dye, which they sold at ports around the Mediterranean.

The Berbers of the desert were not mariners, nor were they especially interested in harvesting these snails and putting them to good use. It fell instead to sailors from far away, who came thousands of miles from the Levantine coast of the eastern Mediterranean, to realize the potential for using these gastropods to make a fortune. The great challenge would come in the business of acquiring them.

For the sea in which these elegantly fashioned beasts lived so abundantly was a body of water very different in character from the placid waters of the Mediterranean. The gastropods were generally to be found, thanks to complex reasons of biology and evolutionary magic, clinging stubbornly to the rocks and reefs in the great and terrifying unknown of the Atlantic Ocean, well outside the known maritime world, and in a place where traditional navigational skills, honed in the Mediterranean, were unlikely to be of much value. To harvest these creatures, any mariners of sufficient boldness and foolhardiness would be obliged to grit their collective teeth and venture out into the deep waters of the greatest body of water it was then possible to imagine.

But they did so, in the seventh century B.C. They did so by blithely setting sail past the Pillars of Hercules, the exit gates of their own comfortable sea, and out into the great gray immensity of the limitless unknown beyond. The sailors who performed this remarkable feat, and yet did so so casually, were Phoenicians; they used sailing ships that were built initially only to withstand the waves of their familiar inland short sea but now had to tackle the much more daunting water of an unknown long sea beyond. There must have been something remarkable about the sailors, yes; but there must also have been something even more so about these particular North African snails that made them worth so much risk.

And indeed there was. First, however, it seems appropriate to set the snails to one side and consider the lengthy and necessarily complex human journey that brought the Phoenicians to Morocco in the first place.

2. ORIGINS

Early man’s march down to the ocean began in remarkably short order. Just what impelled him to move so far and so fast—curiosity, perhaps; or hunger; or a need for space and living room—remains an enigma. But the fact remains that a mere thirty thousand years after the fossil record shows him to have been foraging the grasslands of Ethiopia and Kenya—hunting for elephants and hippos, gazelles and hyenas, building shelters and capturing and controlling lightning-strike fires—he began to trek southward through Africa, a lumbering progress toward the continent’s edge, toward the southern coastlines and a set of topographical phenomena the existence of which he had no inkling.

The weather was becoming cooler as he went: the world was entering a major period of glaciation, and even Africa, astride the equator, was briefly (and before it became very cold indeed) more climatically equable, more covered with grassland, less wild with jungle. So trekking down south along the Rift was perhaps the least complicated of early man’s explorations—the mountain ranges on each side offering him a kind of protection, the rolling grassy countryside more benign than the jungles of before, the rivers less ferocious and more crossable. And so in due course, and after long centuries of a steady southern migration, man did reach the terminal cliffs, and he did find the sea.

He would have been astonished to reach what no doubt seemed to be the edge of his known world, at the sudden sight of a yawning gap between what he knew and what knew nothing about. At the same time, and from the safety of his high and grass-capped cliff top, he saw far down below him a boiling and seemingly endless expanse of water, thrashing and thundering and roaring an endless assault against the rocks that marked the margin of his habitat. Quite probably he was profoundly shaken, terrified by the sight of something so huge and utterly unlike anything he had known before.

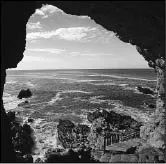

Yet he didn’t run yelping back to the safety of the savannah. All of the recently discovered evidence suggests he and his kin stopped where they were and made shelter on the shore. They chose to do so in a large cave that was protected from the waves below by its location well above the high-tide levels. Then—whether timidly or boldly or apprehensively we will never know—he eventually clambered down and made it onto the beach proper. Then, while keeping himself well away from the thunder of the breakers, he knelt first to investigate, just as a child might do today, the magical mysteries of the seashore tide pools.

With the cliffs of land on one side and the brute majesty of the water crashing on the other, he was briefly captivated by the entirely new world of the pools. He gazed into their depths, which were crystal clear, yet fronded with green and furtive with darting movement. He dipped his finger into the water, withdrew it, tasted—it was very different from all he had known before, not sour and brackish like the poorer of the desert wells, but not fresh and sweet, probably not good for him to drink.

But nonetheless, it supported some kinds of life. The pool, as he looked at it more closely, was furiously alive with creatures—crabs, small fish, beasts with shells, weeds, anemones. And so by the same process of trial and error that had dominated his feeding and foraging habits on land in the millennia before, he eventually discovered in the pools an abundance of food for himself and his family. It was, moreover, good and nutritious food, and it was of a kind that he could hunt without running, that he could eat without cooking, that he could gather without putting his life at risk. Moreover, and mysteriously, it was a food that was somehow magically replenished with every one of the twice-daily refillings of the small watery world that lay before him.

Inevitably, man’s fascination with this strange new aqueous universe brought him to settle by the sea. He had come at last to Pinnacle Point.

3. COASTING

The Western Cape, the administrative name for the most southerly corner of South Africa, is where the waters of the Indian Ocean blend into the cold chill of the South Atlantic. It is a fearfully dangerous coastline, heaped with shipwrecks: oil tankers too big for Suez pass south of Cape Agulhas and then hug the coastline on their way to or from the wellheads, and seem to collide with each other with a dismaying frequency, resulting usually in the spillage of much unattractive cargo and the deaths of scores of African penguins.

I have sailed in these waters and know them to be very trying. Almost all vessels like to keep close to shore to avoid the notoriously extreme waves of the deeper sea, and there are few harbors to which one can run in the event of bad weather. The combination of crowded sea-lanes (all littered with local fishing vessels, too), of cold and rough waters, and a forbidding and havenless rockbound coastline is one that few mariners—and certainly few quasi-inept strangers, as I used to be—care to experience.

I still have my old South Africa Pilot, the blue-backed sailing directions I used on the yacht. The rather beautiful Vlees Bay it notes as a landmark lies between two rocky headlands—Vlees Point to the south and, nine miles to its north, Pinnacle Point. Back when the Pilot was written, its hydrographer-authors noted the presence near Pinnacle Point of “a group of white holiday bungalows,” noting them not for aesthetic reasons, but because they would have provided visible markers for ships making their way along the coast.

This gathering of second homes has transmogrified over the thirty years since the Pilot was written into an almighty village—the Pinnacle Point Beach and Golf Resort—devoted to costly seafront hedonism. The peddlers of the resort like to say that the sea air, the Mediterranean climate, the white water, and the peculiar local floral kingdom known as fynbos, which here renders their ironbound coastal landscape unusually attractive, all combine to transform the place into “a new Garden of Eden.”

Little do they know how apposite their slogan is. Pinnacle Point may be on the verge of enjoying fame among professional golfers and retired businessmen—but it has been known for very much longer to archaeologists consumed by the history of early man. For Pinnacle Point appears to be the place where the very first human beings ever settled down by the sea. Specifically there is a cave, known to the archaeological community as PP13B, situated a few score feet above the wave line (though not quite out of earshot of the ninth tee), where evidence has been found showing that the humans who first sheltered there did such things as eat shellfish, hone blades, and daub themselves or their surroundings with scratchings of ocher. And they did so, moreover, 164,000 years ago, almost exactly.

An American researcher, Curtis Marean, from the School of Evolution and Social Change at Arizona State University, was among the first to realize the importance of the cave, in 1999. He had long suspected, from what he knew of Africa’s chilly and inhospitable climate during the last major glaciation, that such humans as existed would probably travel to cluster along the southern coast, where the ocean currents brought warmer water down from near Madagascar, and where food was available both on the land and in the sea. He decided that these humans probably sheltered in caves—and so he looked along the coastline for caves that were sufficiently close to the then sea level to allow the humans to get to the water, yet sufficiently elevated that their contents weren’t washed away by storms and high tides. Eventually he found PP13B and had a local ostrich farmer build him a complicated wooden staircase so his graduate students didn’t fall to their deaths clambering to the cave mouth—and began his meticulous research. Marean’s paper, published in Nature eight years later, drily recorded a quite remarkable find.

This large sea cave in the South African coast appears to be one of the places where humankind first reached the shores of the sea. Researchers have found evidence that these humans also ate their first seafood here: shell fragments include oysters, mussels, and limpets.

There was ash, showing the inhabitants lit fires to keep themselves warm. There were sixty-four small pieces of rock fashioned into blades. There were fifty-seven chunks of red ocher, of which twelve showed signs of having been used to paint red lines on something—whether walls, faces, or bodies. And there were the shells of fifteen kinds of marine invertebrates, all likely to have been found in tide pools—there were shore barnacles, brown mussels, whelks, chitons, limpets, a giant periwinkle, and a single whale barnacle that the Arizonans believe came attached to a whale skin found washed up on the beach.

How the community decided to dine on shellfish remains open to conjecture. Most probably the inhabitants saw seabirds picking up the various shells, cracking them on the rock shelves, and gorging themselves on the flesh within. Disregarding the so far unsaid assertion that it was a brave man who ate the first oyster, the cave dwellers swarmed down to the oceanside and promptly wolfed down as many mollusks as they could find—eventually repeating what must have been this very welcome gastronomic adventure on every subsequent occasion that the tides generously provided them with more.

The experience had a signal effect on this small colony, and on humankind in general—which makes it all the more remarkable that the financiers of the local golf course chose “Garden of Eden” as their slogan. The effect was of far greater significance than might be suggested by a mere change of diet, from buffaloes to barnacles, from lions to limpets. The limitless abundance of nourishing food meant the settlers could now do what it had never occurred to them to do before—they could settle down.

They could at last begin to consider the rules of settlement—which included the eventual introduction of both agriculture and animal husbandry and, in good time, civilization.

Moreover, their ocher colorings suggests that for the first time these cave colonists began to employ symbols—signs perhaps of warning or greeting, information or suggestion, pleasure or pain, simple forms of communication that would have the most enduring of consequences. An early seaside human might go down to a certain crab-rich tide pool and merely expect or hope that others would follow him. But then he might decide to create a sign, to use his recently discovered color-making stick to mark this same tide pool with an indelible ocher blaze—ensuring at a stroke that all his cave colleagues would now be able to identify the pool on any subsequent occasion, whether its initial finder went there or not. Thus was communication initiated—and from such symbolic message making would eventually emerge language—one of the many kinds of mental sophistication that distinguish modern man.

4. DEPARTURES

The Atlantic, at its beginnings, was a very one-sided ocean, with many peoples distributed along its eastern coasts and yet for many thousands of years no one—no human or humanoid—on its western side. Moreover, its populated coasts were settled initially by newcomers from the continental heartlands, who had little experience with or aptitude for the ways of the sea. Not surprisingly it took a long time for sailors to venture any distance from the coastline; it took thousands of years for the islands within the Atlantic to be explored; and it took an inordinately long time for anyone to cross the ocean. It was to remain a barrier of water, terrifying and impassable, for tens of thousands of years.

Today’s research, which permits this kind of certainty, is hugely different from the archaeological diggings and probing that went on since before Victorian times. The unraveling of the human genome in 2000 made it possible to find out who in antiquity settled where, and when, simply by examining in great detail the DNA of the present-day inhabitants. The romance of finding potsherds and pieces of decorative artwork remains, of course, but for speedy determination of the spread of humankind, no better way can be devised than the computerized parsing of the genetic record.

Communities were already forming on the Atlantic’s east side while native newcomers were still nervously pushing their way through the woodlands in the west. The first Neolithic peoples in the Levant had already created their world’s first town, Jericho. By now all the world’s peoples were Homo sapiens; no other human kind had m...