- 784 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rightful Heritage by Douglas Brinkley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

THE EDUCATION OF A HUDSON RIVER CONSERVATIONIST, 1882–1932

CHAPTER ONE

“ALL THAT IS IN ME GOES BACK TO THE HUDSON”

I

There was never a eureka moment that transformed Franklin D. Roosevelt into a dyed-in-the-wool forest conservationist. His passion for the natural world was instead an emotion, inclination, and inherited disposition. Throughout his life he firmly believed that natural surroundings influenced a person’s health, social behavior, and mood for the better. “Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s family owned land in and around Poughkeepsie and along the banks of the Hudson River for four generations,” his wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, wrote, “but even before that his Roosevelt ancestors lived just a bit farther down the Hudson River . . . so the river in all of its aspects and the countryside as a whole were familiar and deeply rooted in my husband’s consciousness.”1

If tourists with an active imagination started at the Hudson River’s headwaters in a lake high in the Adirondacks, and traveled 315 miles south to New York Bay, they’d see a grand cavalcade of American history unfold. To Roosevelt, the Hudson, a tidal river where Atlantic seawater flooded far upstream, was the great wellspring of the nation. The river was the first in America to be explored by Europeans, its waters beheld the first steamships to operate successfully, and its banks were the birthplace of the nation’s first lucrative railroad.2 A connoisseur of Hudson River Valley history, Roosevelt concurred with Dutch explorer Henry Hudson, who in 1609 found the river’s leafy shores and bluffs “as pleasant a land as one can tread upon.”3

America’s only four-term president was born on January 30, 1882, in the provincial village of Hyde Park, New York, amid rich Dutchess County farm country. His parents, James and Sara Roosevelt, were both from prominent Hudson Valley families, on opposite sides of the river. The tranquil beauty of the Hudson River stitched the families together: the Roosevelts on the east side (Hyde Park) and the Delanos on the west (Newburgh). In 1880, James Roosevelt was a well-preserved widower of fifty-four—with one child, a son named James, who was known as “Rosey”—when he married Sara Delano, a woman twenty-six years his junior. Franklin, their only child together, was named after Sara’s favorite uncle.

James Roosevelt graduated from Union College in 1847 and Harvard Law School four years later. He increased his inherited fortune through investments in real estate, bituminous coal, banking, and railroads. Fancying himself a country squire, he had the leisure of spending quality time with little Franklin, exploring nature, teaching him to honor trees as the noblest and weightiest of all living organisms, to respect the ethics of land stewardship, and to be a country gentleman, too. Franklin’s nickname for his father was “Popsy,” a term of endearment. “Mr. James passed on intact his own fondness for the outdoors,” historian Geoffrey C. Ward explained. “He loved trees, for example, knew their varieties, would allow none to be cut unless they were dead or diseased, and he made sure his son felt the same way.”4

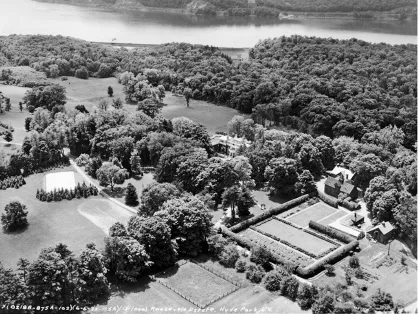

In 1867 James Roosevelt had purchased an estate in Hyde Park. He later acquired additional acreage adjacent to it on both sides of the Albany Post Road.5 Like most upscale properties in the mid-Hudson region, the Springwood estate—simply called “Hyde Park” by most Roosevelts—had Hudson River access as well as fruit orchards, vegetable gardens, a stocked pond, wide fields, and thick woodlands. It would be FDR’s home throughout his life. Covering one square mile, the over six-hundred-acre estate formed a long, slender parallelogram, with its west side bordering the mile-wide river.6 Though the rambling Main House had unpretentious amenities, it boasted a marvelous view of the scenic Hudson. From his third-floor bedroom little Franklin could look west across the river to see the hardwood forests of the Catskill Mountains. The Hudson River Valley became increasingly sanctified to many Americans after the Civil War, as magazines like Scribner’s and the Atlantic Monthly depicted the region’s pastoral charms; so did Currier and Ives in such lithographs as “Hudson River–Crow’s Nest,” and “On the Hudson.”7

Springwood, Franklin Roosevelt’s lifelong home in Hyde Park, New York, was photographed from the air in 1932, looking to the southwest. The house is nestled among the trees (center). Franklin sailed and ice-boated on the Hudson River (at top), while his mother took pride in the formal rose gardens (right).

Whenever Franklin played at Springwood, collecting leaves in the hemlock forest, tobogganing down snowy hills, catching minnows in Elbow Creek, or chasing rabbits along the riverfront, he was living what Leo Marx called—in his study of agrarian romanticism, The Machine in the Garden—“the pastoral ideal.”8 Photos exist of Franklin riding his Welsh pony (Debby), playing with the family border collie (Monk), and leading his pet goat into a “secret garden.” When the Hudson froze there were marvelous sleigh rides down the river to Newburgh. Locals made a livelihood selling blocks of ice to New York City and beyond.9 In the spring, when the snow melted, Franklin would wear rubber hip boots and sail little boats on the Hudson.10 In a flight of imagination, he would pretend hemlocks were ships, hanging sheets on their thick branches to make them resemble the mast of the USS Constitution (he had a small replica of the famous War of 1812 frigate in his bedroom trunk). He could only imagine the aquatic universe under the rippling surface of the river—the eels, water plants, and detritus from ships past. Memories of these Hyde Park outdoor adventures turned FDR, as an adult, into a tireless booster of the Boy Scouts of America; he believed that all young men deserved to experience the joys of nature just as he had done.11

As an only child tutored at home, Franklin had only a few playmates in Hyde Park: namely Edmond Rogers, Mary Newbold, and his niece Helen Roosevelt. Instead, during his leisure hours, Franklin roamed the estate’s grounds, nurtured by chittering squirrels and drumming doves. Wandering around the terraced hills that rose from the Hudson River to Springwood’s Main House, tracking robins and vireos, turning horses out to pasture, he developed an almost tangible intimacy with the land, never taking the staggering beauty of the Hudson River Valley for granted.12 “The land existed for FDR in time as well as space,” historian John Sears explained. “It had a history, and that history was organically connected to the present.”13 Dutchess County had once been inhabited by Algonquian-speaking Wappinger Indians, one of the northernmost of the Delaware peoples. Young Franklin often scoured his property for artifacts and relics.

Whenever Franklin arrived home after one of his Indian relic hunts, invariably scuffed up, his mother, Sara Delano Roosevelt, would ask him scoldingly and in alarm, “Where have you been?”

“Oh, out in the woods,” was the usual answer.

“What doing?” Sara would ask.

“Climbing trees.”14

In the 1880s there was a backlash in some circles against rapacious industrialists who mauled landscapes, like those of the Hudson River Valley and the Adirondacks, for timber and minerals. Painter Thomas Cole, in his seminal “Essay on American Scenery,” bemoaned what he called the “ravages of the axe,” which were destroying pastoral landscapes.15 Deeply concerned about deforestation, the Roosevelts wanted state regulations and industry safeguards in place to fight wanton extraction. While much of nineteenth-century New York City smelled of smoke, coal, and oil, FDR’s upstate environment during his childhood was pine-scented. As landscape perservationsists his parents sought to keep the Hudson River Valley green for future generations.

Since most of the land in New York where reforestation was especially needed during the Gilded Age was in the hands of private owners, the most practical solution to saving forests was acquiring more public lands. In 1885, the state launched two major forest preserves, which covered nearly a million acres in the Adirondacks and, on a much smaller scale, the Catskills. Unfortunately, the law was weak. In 1894, when FDR was twelve, the state superseded it with an amendment mandating that all state-owned forests be “forever kept as wild.” After that, forest preserves were regulated to protect nature, first and foremost. Further, they were part of a movement in New York that allowed them to exist amid privately owned parcels in which commercial development would be largely restricted by the state. As these innovative “parks” coalesced, they were located across massive tracts in the Catskills and Adirondacks. Chopping timber in the “forever wild” forest preserves in the parks was banned outright, because of the amendment. On the private lands in the parks, it was overseen by the state to ensure conservation was at least considered. These developments in forestry, followed closely by the Roosevelt family while Franklin was growing up, gave birth to the modern wilderness preservation movement.16

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) joined the state of New York in visionary protection of American forestlands. At the prodding of grassroots activists and conservation-minded presidents such as Benjamin Harrison and Grover Cleveland, Congress preserved vast forests in the West. On the intellectual front, George Perkins Marsh’s 1864 environmental manifesto Man and Nature; Or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action, which warned of the perils of deforestation, was influential among American conservationists. Picking up Marsh’s torch was Charles Sprague Sargent, the director of Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum, who worried about shortsighted forestry practices. From 1887 to 1897 Sargent published his Report on the Forests of North America, which called for immediate reform of destructive timber-management practices throughout the nation. The Roosevelts of Hyde Park happily subscribed to Sargent’s Garden and Forest magazine, a weekly aimed at fostering awareness of and interest in woodlots, horticulture, landscape design, and scenic preservation.17

Sara’s father, Warren Delano, a Republican, had hired the building and landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing, whose portfolio included the White House and U.S. Capitol grounds, to redesign his estate, Algonac (a name derived from an Algonquin Indian term meaning “hill and river”). Situated on the bluffs two miles above the town of Newburgh, the mansion left a lifelong impression on FDR. Algonac had originally been a modest brick-and-stucco house, but Downing enlarged it to forty rooms and situated it toward the south to capture views of the Hudson River, as well as the surrounding mountains. Two towers and a large veranda were also added. It appeared to visitors that Algonac was almost an organic part of the Orange County, New York, landscape, not an intrusion on it. But Warren Delano, the patriarchal millionaire, wasn’t what later generations would consider an environmentalist. He owned coal mines near Johnstown, Pennsylvania, and copper mines in Maryland and Tennessee. (As a consequence, there were towns named Delano in both states.)18 The inside of the manor had heavy carved redwood furniture, teakwood screens, and Buddhist temple bells. On the grounds there were a dozen species of trees. One of FDR’s boyhood loves was embarking on the twenty-mile trip to Algonac, crossing the Hudson on the Beacon-Newburgh ferry. The compound there was so bucolic that the Roosevelts and Delanos used “Algonac” as a code word for “good news.”19

Downing, who made his home along the Hudson all his life, was an early influence on urban parks. He promoted his philosophy of landscape architecture, designed to be more authentically American than manicured English gardens, in The Horticulturist, a magazine he founded, and in A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America (1841). His credo of living in harmony with nature took root throughout the Hudson River Valley. Downing went from delivering plants to wealthy clients—the “River Families,” as the local landed gentry were known—to being invited into their homes for grand dinner parties. Even after his death at the age of thirty-six, his popularity among River Families like the Roosevelts and Delanos remained strong.

Both James and Sara Roosevelt concurred with the popular Jacksonian novelist Catherine Sedgwick, who believed that “no American in good report, whether he be rich or poor,” should “build a house or lay out a garden without consulting Downing’s work.”20 Downing had a deep influence on Franklin’s philosophy of living in harmony with nature. The Roosevelts adhered almost religiously to his principle of maintaining woodlands and making the natural setting important.21 “We believe,” Downing wrote, “in the bettering influence of beautiful cottages and country houses—in the improvement in human nature necessarily resulting to all classes.”22 Using local wood and stone was Downing’s way of having his homes sink into the natural landscape. What James and Sara Roosevelt took from Downing—and passed on to Franklin—was the concept that Springwood should be a “middle landscape,” a “rural Arcadia . . . aesthetically balanced between the extremes of wilderness and city.”23

James Roosevelt carefully designed Springwood’s grounds with refined simplicity, letting nature set the terms, in what Downing termed the “accessible perfect seclusion” from New York City.24 He considered his prime riverfront acreage his greatest asset; the land would bring solace to his son Franklin for the rest of his life. With more than six hundred contiguous acres to work with—some of them pastureland and wetlands—James adopted an informal arrangement of landscape elements. On the grounds surrounding the house, he included a variety of tree species, laid out an irregular placement of plants, and created so...

Table of contents

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Part One: The Education of a Hudson River Conservationist, 1882–1932

- Part Two: New Deal Conservation, 1933–1936

- Part Three: Conservation Expansion, 1937–1939

- Part Four: World War II and Global Conservation, 1940–1945

- Epilogue: “Where the Sundial Stands”

- Appendix A: National Park System Areas Affected Under the Reorganization of August 10, 1933

- Appendix B: National Wildlife Refuges Established under Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933–1945

- Appendix C: National Parks and National Monuments Created by Franklin D. Roosevelt Following the Reorganization of August 10, 1933

- Appendix D: Establishment and Modification of National Forest Boundaries by Franklin D. Roosevelt, March 1933 to April 1945

- Appendix E: The Nine Civilian Conservation Corps Areas

- Appendix F: Civilian Conservation Corps—Basic Facts

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index

- Photos Section

- About the Author

- Also by Douglas Brinkley

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher