1

Sabotage by Obedience

Insist on doing everything through channels. Never permit shortcuts to be taken in order to expedite decisions.

The deal was dead in the water. The company was going to lose a long-standing account. Michael knew it, but he couldn’t do anything about it.

The client’s representative, Samantha, had called unexpectedly, late in the afternoon, saying that a competing software firm had pitched a package deal—software, training, support—at a slightly lower rate than she was paying. The competitor was offering to include more training time. Although Michael’s firm had already made its best-and-final offer, couldn’t they sweeten it just a bit to match the competing bid? Samantha had to have an immediate answer; she needed to select the winning bid by the end of the day.

“I can’t do that,” Michael thought, feeling a weight in the pit of his stomach. At their most recent sales conference Michael’s boss, the vice president of sales, had made it clear that all revisions to bid prices had to get either his or the division head’s approval “in order to rein in some cowboy pricing that’s been giving away the store.”

Left to his own devices, Michael would have matched the competitor’s offer. He knew Samantha’s company well, and he felt sure that he could make up the difference with add-on services in just a few months. But he didn’t have the authority to lower the bid, and he knew his boss, en route to Europe with the division head, was unreachable.

Michael isn’t trying to sink his company. He’s a hard worker. He loves his job. And he’s just following the rules, which were created to ensure that the company’s salespeople didn’t jeopardize the company by promising things they couldn’t profitably deliver. By insisting on going through channels—that is, adhering closely to the procedures put in place by his boss and division head and going to his bosses for approval for any and every situation that falls beyond the perceived scope of his position—Michael is technically doing the “right” thing.

But his good behavior is about to cost his company a contract. Michael knows that without those few minor—but unobtainable—concessions, the deal is finished. And losing this deal is, he knows, the wrong thing.

You’d think that saboteurs wouldn’t be model employees or colleagues. You’d think that they would be the people who make a habit of trying to get around the rules, or taking lots of shortcuts. But Michael is what we call an “Obedient Saboteur.” He doesn’t stray from the guidelines set out in the employee handbook or in the processes and rules laid out by the head of the sales department. And it’s his adhering to these rules, not breaking them, that’s about to cost his company a customer.

Obedience—doing exactly what you’re told to do, and not doing things outside your scope of authority—is usually a valuable behavior. It’s predictable, and usually it means that you can work with confidence knowing you’re not making mistakes. What’s more, since you’re “playing by the book,” decision-making can often be reduced to “paint by numbers” simplicity. Organizations run more smoothly most of the time if everyone is following instructions set with no variability. But obedience becomes Sabotage by Obedience—instantly—when it prevents personal judgment from overriding processes that for whatever reason are not working at that moment. That’s what the OSS was counting on. That’s what happened with Michael. And that’s what might be happening in your organization.

When Does Obedience Look like Sabotage?

To tell when this type of sabotage is happening in your organization or group, start by examining the rules you have for governing behavior—formal or implied—and see whether you can explain why each one is there. Think about the kind of work you’re trying to get done, the type of people you’re working with, the nature of their roles, and the relative importance of their individual judgment on the broad objectives you’re trying to accomplish.

For example, the leaders of a retail chain might consider whether their return department is there to help customers make returns rapidly and easily, with a minimum of fuss, or whether it is there to make sure returns are given only if they are justified and all the documentation is in place. Clearly, there’s a balance point between the two. But which is more important? Is that balance point right in the middle? Or is customer convenience more or less important than preventing possible fraud losses?

Then ask: If people had complete freedom to make decisions on their own, at what point would that freedom begin to get you in trouble? Medicine comes to mind as an industry where adherence to procedures and protocols is paramount. And we’re not sure we would be thrilled about food safety inspectors deciding on their own what criteria to use before approving a batch of ingredients.

On the other hand, how much freedom from process do people need in order to be creative, innovative, responsive, and effective in the moment? Suppose a candidate for a minister position contacts the hiring committee to ask some background questions before the interview, and the committee chair is away on vacation? Can someone else answer the candidate’s questions to ensure that the candidate doesn’t lose interest in the position?

What overall message does your group’s culture send about doing things by the book and through channels? And why is that particular message being sent? Is it by design, that is, consciously controlled? Or is it the inadvertent result of hundreds of decisions and policies that have accumulated over time? Should this message still apply? Should it apply across the board to all group members?

The answers to these questions will give you a pretty good understanding of what procedures or norms of behavior are a must—that is, when it is absolutely imperative to go through channels—and when more freedom ought to be allowed. Armed with that knowledge, you can then begin to figure out who might be doing some serious damage by being too good at following the rules.

Senior leaders at Shepley Bulfinch, a prominent national architectural firm, ask these questions of themselves regularly as they strive to refine the firm’s processes for evaluating its pipeline of work. Like many professional services firms, the company asks its principals and project managers to submit regular reports on their upcoming workload. But at one time, managers were required to include in those reports all projects in their pipelines—and the company found itself “blessed,” temporarily, with a number of Obedient Saboteurs who were happy to comply. These managers did just as they were told, including every project in the reports even if it seemed that unpredictable variables might delay some jobs. Other, more realistic, staff did not follow the rules completely. They held back, either excluding risky projects from their reports or at least painting a more conservative picture of timing.

Simply letting the saboteurs go through channels and follow the prescribed submission procedure was creating inaccurate reports that increased the risk of haphazard resource allocation and recurring feast-or-famine situations. So Shepley Bulfinch leaders had to figure out whether it was more important to have an incorrect report than no report at all—or whether they needed to create a third option.

They went with the third option. Project leaders now meet more regularly with the firm’s CFO to create a balanced forecasting mechanism, and managers are routinely encouraged to annotate their forecasts. Identifying when obedience was leading to unwitting sabotage was the first step toward correcting the problem.

Michael Glazer, CEO of the $1.6 billion NYSE retailer Stage Stores, is also constantly assessing company rules. In fact, he told us that when he became CEO, one of the first things he did was to try to get a handle on why certain rules were in place so he could evaluate them effectively. The previous management team had been focused almost entirely on margins. As a result, they had enacted rules regarding purchasing to ensure that margins wouldn’t be too thin. Maybe those rules had saved the company from financial ruin at some point—Glazer didn’t know. What he did know was that when he came on board, Stage Stores buyers were not allowed to stock some of the most attractive, in-demand lines of clothing.

“We had only a very small selection of Nike,” he said. “Our customers would go to our stores looking for brands like Nike and leave unhappy and empty-handed. We forced them to do business with our competitors. Yes, we could make only a thin margin with some popular brands. But if a customer walked out with two tops and a jacket in addition to the Nikes they came in for, we would have made a nice total margin on that overall purchase. The buyers were following a directive that had come right from our senior management team, but their obedience was hurting the business. And they knew it; they just couldn’t do anything about it.”

Glazer, too, is concerned with margins. But once he realized how the existing rules were actually doing harm to the business overall, he started to reevaluate and rework them so that they now guide the company’s buyers but are not so rigid that they prevent buyers from making purchasing decisions that will ultimately help the bottom line.

The Bell Curve Test

You probably know who the squeaky wheels are in your group. These are the people who are out of line a lot; they probably try your nerves. But they’re easy to spot. To ferret out the Obedient Saboteurs (and the flawed rules they may be following), you have to look for the people who don’t make any noise at all.

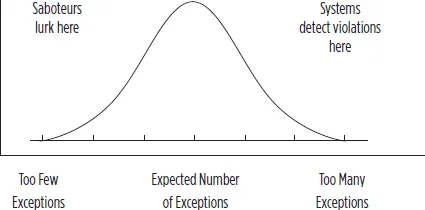

Suppose, for example, you have a night manager of a hotel authorized to provide room upgrades to late-arriving guests. That person can give an upgrade to everyone who walks through the door, or he or she may never give an upgrade at all. You can probably track this behavior pretty easily. To get a sense of where the norms are, create a bell curve where the middle of the curve shows the number of exceptions to the rule that you would expect to see. As the graphic shows, it will be clear, by looking at the far right side of the curve, which employees are pushing the limits on your guidelines—who is likely providing too many upgrades, or upgrades where none is warranted.

But it will also be clear who works at the other extreme—those managers who rarely, if ever, offer an upgrade. Ultimately, those people probably represent the more grievous threat. They’re not your squeaky wheels. They’re invisible. But their behavior is slowly, surely, building rigidity into your company—rigidity that can cause it to crack.

Not every organization regularly gathers the kind of data that make the bell curve test an easy exercise. But if the data are there, particularly for customer-facing activities, then do the test. Exposing the “hidden” side of the curve is a big step toward eliminating Sabotage by Obedience.

Rehabilitate and Prevent Obedient Saboteurs

Once you spot individual Obedient Saboteurs, the remedy can take several forms. It might involve rewriting some of the rules that govern their work (like Shepley Bulfinch and Stage Stores did). But the solution might be much simpler (although not necessarily as easy as it sounds): reviewing the saboteur’s job description or role and making it clear that that person’s judgment is wanted and needed.

For example, if you’re a supervisor and you suspect a lower-level employee of being an Obedient Saboteur, give that person some responsibility that occasionally requires him or her to make a personal judgment. Then follow through with coaching to make sure that he or she understands that a little risky behavior is okay even if the results don’t always pan out.

If the person works at a high level, the antidote is more complex. A higher-level executive might be creating a culture within a department or function that discourages sensible rule-breaking, encourages “cover your rear” behavior, or both, across an entire team. In such cases, all of the team members need to understand their behavior’s negative effects on the organization; the entire team may need some coaching.

To inoculate your organization or working group at a broader level against Obedient Saboteurs, and to make Sabotage by Obedience something that people can talk about comfortably, spot easily, and resolve as needed, take as many of the following four steps as apply to your situation.

Revisit Your Performance Metrics and Incentives

You want your metrics—the things you measure and the ways you measure them—to reinforce your processes and drive the outcomes you seek. You will inadvertently create Obedient Saboteurs if you reward people for adhering to the rules even when common sense tells them not to. To make sure that your metrics are not leading to sabotage, follow these steps:

Catalog the performance metrics you or your company track for each type of job under your supervision. For example, a hotel chain might track how many complimentary room upgrades a front desk supervisor gives out.

Consider whether each metric is necessary. Does it affect the hotel if front desk supervisors give out too many or too few upgrades? It does. Hoteliers believe that giving away too many upgrades devalues the regular rooms and creates expectations that guests should get more than they’re willing to pay for. Too few, however, is a lost opportunity to reward the best customers for their loyalty.

Identify the explicit link between each metric and higher profit. For a hotel, too many upgrades means higher cleaning costs, higher food costs, and lower guest satisfaction when guests are placed in a standard room.

Determine what behavior the obedient employee is expected to follow. The obedient front desk manager should provide the occasional upgrade to frequent guests but must be aware that each upgrade costs the company money.

Ask yourself, “What would happen if someone were to try to drive this metric to an extreme? Would that behavior still be desirable or lead to adverse outcomes?” In our example, the Obedient Saboteur would give out very few, if any, upgrades. In this case, frequent guests who did deserve recognition for their loyalty would not receive any and potentially take their business elsewhere.

Set up your metrics to reveal extreme behaviors. In this example, the measurement system is designed to detect too many upgrades, not too few. The Obedient Saboteur would likely be undetected. The hotel should start flagging front desk supervisors who give too few upgrades relative to their peers,...