- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

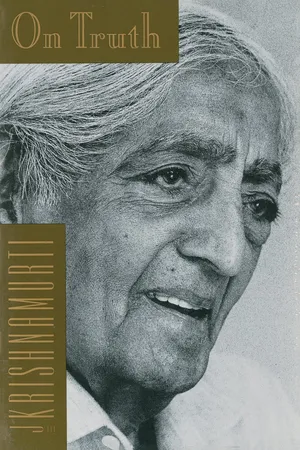

On Truth

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Saanen, 1 August 1975

WHAT IS THE action of a man who is not caught in time? What is the relationship between reality and truth, if there is such a thing as truth, and what is a man who lives in the world of reality all the time to do? Caught in that world of verbal, imaginative reality, the world of conclusions, ideologies, tyrannies, what is a human being to do? Shall we go into that? What is the difference, or what is the relationship, between truth and reality? We have said reality is all that thought has put together, all that thought reflects upon, all that thought remembers as knowledge, experience, and memory. Thought acts in that area, and lives in that area, and we call that reality.

We are saying that the root meaning of that word reality is res, thing. So we live with things, we live with things created by thought as ideas, we live with things called conclusions, which are all verbal, and we have various opinions, judgements, and so on. That is the world of reality. And what is the relationship between that and truth? How shall we find this out? This was one of the problems of the ancient Hindus, and of some philosophers and scientists, both ancient and modern: Is there such a thing as truth, and if there is, is it within the field of reality, or is it outside reality; and if it is outside, what is the relationship between that and reality?

What is the activity of reality? What takes place in the field of reality? Shall we begin with that, and see its meaning, its significance, and its value? And when we have completely understood the field of reality, then we can inquire into the other, not the other way round. Because one’s mind may not be capable of inquiring into truth. But we can inquire into the world of reality, its activity, how destructive or constructive it is, and so on. When we are absolutely clear, logical, sane, and healthy about the world of reality then we can proceed to find out if there is truth. Not ask what truth is, because then we speculate about it, and our speculation is as good as somebody else’s.

So what is activity in the world of reality, both outwardly and inwardly, psychologically? In that world of reality there is always duality, the ‘me’ and the ‘you’, we and they. This duality expresses, acts in the world of reality as nationalities, as religious divisions, as political division and tyrannies and domination; all this is actually going on. So there is this activity of duality—the ‘me’ and the ‘you’, and the ‘me’ separating itself from the actual, and having a conflict with the actual.

The world of reality is created by thought. Thought is movement in time and measure. That thought has created the centre; that centre separates itself from thought, and then that centre creates duality as the ‘you’ and the ‘me’. Not verbally, not intellectually, but actually, does one see the reality of this? This is the truth; ‘that which is’ is the truth. And do I see ‘that which is’? That is, thought creating a centre, that centre assuming power, domination, and creating division between the centre and the periphery. Thought, having created the centre, that centre not only becomes a cohesive, unitary process, but it also acts as a dividing thing. Do you see it as clearly as you see this tent? The tent is real, it has been created by thought; it is independent of thought but it is actual.

So we live outwardly and inwardly, psychologically, in the field of reality, which is basically not only fragmentary but divisive. It is dual, divided. That is our life. One of the symptoms of this division is the centre trying to control thought, trying to control desire, trying to control various appetites, various reactions. So the centre becomes the factor of division. This is fairly simple. That is, conflict is always part of the field of reality. That conflict is not only within myself, but outward, in my relationship to others.

Conflict is one of the principles of reality, as division is one of the principles, and from that division conflict arises. This is factual. The centre separates itself from violence, and then that centre acts upon the violence, controlling it, dominating it, trying to change it into non-violence, and so on; from the centre there is always the effort made to control, to change. This is happening politically, in the democratic world as well as in the tyrannical world where the few dominate the many. The few are the centre—I don’t know if you see the beauty of all this—and the few want unity, and therefore they must dominate.

So in the field of reality, division is one of the basic principles. That is, the centre trying to control thought. Let’s stick to this and understand it. We try to control anger, we try to control various forms of desire, always from the centre—the centre being what thought has created that has become permanent, or rather attributed to itself the quality of permanency.

Q: You can do this in the privacy of thought.

K: If you are by yourself you can do this, but if you are with others you cannot live a life in which there is no control—is that it? I don’t think you realize what you have said. That if you are by yourself perhaps you could do this, but if you have to live with others you cannot do this. Who are the others? We divide by thought as ‘you’ and ‘me’, but the actuality is, you are me, I am the world, and the world is me, the world is you. I wonder if you see this.

Q: That is not true.

K: I think it would be more correct if you used the word incorrect rather than say it is not true. Correct means care; it comes from the word care, accurate; accurate means care. You say, that is not so. Now let’s look at it. Basically, whether you live in America, France, Russia, China, or India, we are the same—we have the same suffering, the same anxiety, the same grief, arrogance, uncertainty. Environmentally, culturally, we may have different structures and therefore act superficially differently, but fundamentally you are the same as the man across the border.

Q: I need privacy.

K: Oh, you still want privacy. Who is preventing you? I don’t understand the question. If you say, ‘I still want privacy’, you mean you still want to be enclosed by a house, by a garden, by a wall round your house, or enclosed so as not to be hurt. So you say, ‘I must have a wall around myself in order not to be hurt’.

As we were saying, in the field of reality, conflict and duality are the actual things that are going on—conflict between people, conflict between nations, conflict between ideals, conflict between beliefs, conflict between states, armaments—the whole field of reality is that. It is not an illusion, maya, as the Hindus would say. In Sanskrit ma means measure, so they say that in the field of reality there is always measurement, and therefore that is illusory because measurement is a matter of thought, measurement is a matter of time, from here to there, and so on. They said that is illusion. But the world they wanted is also an illusion created by thought.

So in the field of reality can one live completely without control? Not permissiveness, not doing what you want to do, because that is too childish. Because you can never do whatever you want to do. Is it possible to live a life without a shadow of conflict?

Q: It seems that when we are aware of all these processes that thought tries to control, this brings conflict and then to control thought brings more conflict. So why control?

K: No, sir, if I may go into it a little bit. Have you ever tried, or known how, to act without control? You have appetites—sexual, sensory appetites. To live with those appetites, not yielding to them, not suppressing them, nor controlling them, but see these appetites and end them as they arise? Have you ever played that—not ‘played’, have you ever done this?

Q: It’s impossible.

K: No, sir, I’ll show it to you. Don’t say you can’t do anything, the human mind can do anything. We have gone to the moon; before this century they said ‘impossible’, but we have gone to the moon. Technologically you can do anything, so why not psychologically? Find out; don’t say, ‘I can’t, it’s impossible’. Look, go into it step-by-step and you will see it. You see a beautiful house, a lovely garden, a desire arises, and how does this desire arise? What is the nature of desire? And how does it arise? I’ll show it to you. There is visual perception of a house with a beautiful garden; it is architecturally beautiful, with nice proportions, lovely colours, and you see it. Then that vision is communicated to the brain; there is sensation; from sensation there is desire; and thought comes along and says, ‘I must have it’, or ‘I can’t have it’. I don’t know if you have watched all this. So the beginning of desire is in the beginning of thought. Thought is physical as well as chemical. There is the perception of that house, sensation, contact if you touch it, and desire and thought. This happens, sexually, visually, psychologically, intellectually.

There is that beautiful house, the seeing, the sensation, the desire. Can that desire end, not move with thought as possessing and so on? The perception, sensation, desire, and the ending. Not thought coming along and saying, ‘I must’—in that there is no control. I am asking if you can live a life in the world of reality without control. All action comes from a desire, a motive, a purpose, an end. Surely this is simple, isn’t it?

You eat a good, tasty omelette; what takes place? The brain registers the pleasure, and demands that pleasure be repeated tomorrow. But that omelette is never going to be the same. What we are trying to point out is: to taste and not let it register as a desire, as a memory, and end it.

Q: We are not quick enough to stop the thought.

K: Therefore learn. Let’s learn about it, not how to do it. You see, one’s mind, or brain, is traditional: You are always saying, ‘I can’t, tell me what to do’—that is the pattern of tradition. What we are saying is very simple: which is, the seeing, the sensation, and the desire. You can see the movement of this in yourself, can’t you? When you see a beautiful car, a beautiful woman, or a beautiful man, or whatever, sensation arises, and desire. Now be alert to watch it, and you will see, as you watch it, that thought has no place.

I am suggesting that in the field of reality conflict is the very nature of that reality. So if there is an understanding, a radical change, in you, if there is the ending of conflict in a human being, then it affects the whole consciousness of man, because you are the world, and the world is you. Your consciousness with its content is the content of the world.

So we are asking: Can a human being live in the world of reality without conflict? Because if he cannot, then truth becomes an escape from reality. So he must understand the whole content of reality, how thought operates, what the nature of thought is.

The field of reality is all the things that thought has put together, consciously or unconsciously, and one of the major symptoms of that reality, a disease of that reality, is conflict—between individuals, between classes, between nations, between you and me. Conflict outwardly and inwardly is between the centre that thought has created and thought itself, because the centre thinks it is separate from thought. There is a conflict of duality between the centre and the thought; and from that arises the urge to control thought, to control desire.

Now is it possible to live a life in which there is no control? I am very careful in using that word control, which does not mean doing what you want, permissiveness, all the modern extravagances that have become vulgar, stupid, meaningless. We are using the word control in quite a different sense. One who would want to live in complete peace must understand this problem of control. Control is between the centre and thought—thought taking different forms, different objects, different movements. One of the factors of conflict is desire, and its fulfilment. Desire comes into being when there is perception and sensation. That’s fairly simple and clear. Now can the mind be totally aware of that desire and end it, not give it movement first?

Q: There is no recording in the brain as memory, which then gives vitality and continuity to desire.

K: That’s right. I don’t know if you get this point. I see a beautiful picture and one response is to have it. Or I may not have that response, I may just look at it and walk off, but if there is a response to possess it, then that sensation as desire is registered in the brain and the brain then demands the possession of it and the enjoyment of it. Now can you look at that picture, see the desire, and end it? Please experiment, it is so simple once you understand the whole movement of it.

Q: Sir, I don’t recognize that I have a desire until afterwards. In other words, there is no recorder in my mind that tells me I am having desire.

K: We said that conflict seems to be the nature of the world of reality. And we are trying to find out if it is possible to live without conflict. And we said conflict arises when there is duality, the ‘me’ and the ‘you’, and the centre created by thought and thought itself. And the centre tries to control, to shape thought. Therein lies the whole problem of conflict. And desire arises through sensation—sensory perception. And sensory perception of objective things involving belief is illusion. I can believe that I am something when I am not; therefore, there is the problem of conflict. So is it possible to live a life totally without conflict? I do not know if you have ever put this question to yourself. Or do we live in the world of tradition and accept that world, that conflict, as inevitable?

Q: Sir, I am not conscious of living in conflict.

K: All right, then you say, ‘I am not conscious that I live in conflict’. We are talking over together this question of reality and truth. That’s how this began. We said that unless you understand the whole nature of reality with all its complexities, mere inquiry into what truth is is an escape. And we are saying let us look into the world of reality, the world of reality that thought—and nothing else—has created. In that world of reality, conflict is the movement of life. I may not be conscious of that conflict sitting here but unconsciously, deeply, there is conflict going on. This is simple enough.

Conflict takes many forms, which we call noble and ignoble. If a man has ideals and is trying to live up to those ideals—which is conflict—we call him marvellous, a very good human being. Those ideals are projected by thought. And the centre pursues that and so there is conflict between the ideal and the actual. This is what is happening in the world of tyranny, dictatorship. The few know what they think is right and it is for the rest to follow. So this goes on all the time. And it is the same with regard to authority—the authority of the doctor, the scientist, the mathematician, the informed man, and the uninformed man. The disciple wants to achieve what his guru has, but what the guru has is still in the world of reality. He may talk about truth but he is conducting himself in the world of reality, using the methods of reality, which is division between himself and the disciple. This is so obvious.

From Truth and Actuality, Saanen, 25 July 1976

Questioner: Is a motive necessary in business? What is the right motive in earning a livelihood?

Krishnamurti: What do you think is right livelihood? Not what is the most convenient, not what is the most profitable, enjoyable, or gainful; but what is right livelihood? Now, how will you find out what is right? The word right means correct, accurate. It cannot be accurate if you do something for profit or pleasure. This is a complex thing. Everything that thought has put together is reality. This tent in which we meet has been put together by thought; it is a re...

Table of contents

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Poona, 3 October 1948

- Rajghat, 23 January 1949

- Rajahmundry, 20 November 1949

- Bombay, 12 March 1950

- London, 23 April 1952

- Talk to Students at Rajghat, 31 December 1952

- Bombay, 8 February 1953

- Poona, 10 September 1958

- From Truth and Actuality, Brockwood Park, 18 May 1975

- Saanen, 1 August 1975

- From Truth and Actuality, Saanen, 25 July 1976

- Conversation at Brockwood Park, 28 June 1979

- Ojai, California, 8 May 1980

- Bombay, 3 February 1985

- Bombay, 7 February 1985

- Bombay, 9 February 1985

- From Last Talks at Saanen 1985, 21 July 1985

- From Last Talks at Saanen 1985, 25 July 1985

- Brockwood Park, 29 August 1985

- Sources and Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Also by J. Krishnamurti

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access On Truth by Jiddu Krishnamurti in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.