eBook - ePub

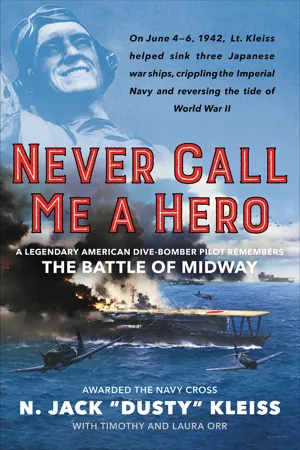

Never Call Me a Hero

A Legendary American Dive-Bomber Pilot Remembers the Battle of Midway

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Never Call Me a Hero

A Legendary American Dive-Bomber Pilot Remembers the Battle of Midway

About this book

The bomber pilot whose bravery in the Battle of Midway changed the course of WWII recounts his story in this extraordinary memoir: "An instant classic" (

Dallas Morning News).

On June 4, 1942, above the tiny Pacific atoll of Midway, Lt. (j.g.) "Dusty" Kleiss piloted his SBD Dauntless into a near-vertical dive aimed at the heart of Japan's Imperial Navy. The greatest naval battle in history raged around him as the U.S. desperately searched for its first major victory of the Second World War. Then, in a matter of seconds, Dusty Kleiss's daring 20,000-foot dive helped forever alter the war's trajectory.

Amid blistering anti-aircraft fire, the twenty-six-year-old pilot zeroed in on the aircraft carrier Kaga, one of Japan's most important capital ships. He released three bombs at the last possible instant, then desperately pulled out of his gut-wrenching dive as Kaga erupted in an inferno.

Dusty returned to the air that same afternoon, fatally striking the enemy carrier, Hiryu. Two days later, he contributed to the destruction of the cruiser Mikuma, making Dusty the only pilot from either side to sink three ships. By battle's end, the humble young sailor from Kansas had earned his place in history—and yet he stayed silent for decades.

Now his long-awaited memoir, Never Call Me a Hero, tells the Navy Cross recipient's full story for the first time, offering an unprecedentedly intimate look at the "the decisive contest for control of the Pacific in World War II" ( New York Times)—and one man's essential role in helping secure its outcome.

On June 4, 1942, above the tiny Pacific atoll of Midway, Lt. (j.g.) "Dusty" Kleiss piloted his SBD Dauntless into a near-vertical dive aimed at the heart of Japan's Imperial Navy. The greatest naval battle in history raged around him as the U.S. desperately searched for its first major victory of the Second World War. Then, in a matter of seconds, Dusty Kleiss's daring 20,000-foot dive helped forever alter the war's trajectory.

Amid blistering anti-aircraft fire, the twenty-six-year-old pilot zeroed in on the aircraft carrier Kaga, one of Japan's most important capital ships. He released three bombs at the last possible instant, then desperately pulled out of his gut-wrenching dive as Kaga erupted in an inferno.

Dusty returned to the air that same afternoon, fatally striking the enemy carrier, Hiryu. Two days later, he contributed to the destruction of the cruiser Mikuma, making Dusty the only pilot from either side to sink three ships. By battle's end, the humble young sailor from Kansas had earned his place in history—and yet he stayed silent for decades.

Now his long-awaited memoir, Never Call Me a Hero, tells the Navy Cross recipient's full story for the first time, offering an unprecedentedly intimate look at the "the decisive contest for control of the Pacific in World War II" ( New York Times)—and one man's essential role in helping secure its outcome.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

KANSAS CHILDHOOD

1916–1932

I was born on March 7, 1916, in Coffeyville, Kansas. My parents were John Louis Kleiss and Lulu Dunham Kleiss. In 1859, the Kleiss family left its home in Germany and settled in Wisconsin. My grandfather, John B. Kleiss, was born during the year of the immigration, the first of my line to be born in the United States. My father—who was called “J. L.” by his friends—was born on August 21, 1888. He lived in Wisconsin for much of his life, working as a master woodworker for a railroad company, but he later found employment as an insurance salesman for Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York. That job brought him to Kansas. My mother, Lulu Isabel Dunham, was born on March 17, 1882, in Logan County, Illinois. Her family traced its lineage to Peter Banta, a New Jersey scout for the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. My mother was an expert typist, possessed exquisite handwriting, and worked for the local Dorcas Society, a sewing club that donated homemade clothing to the poor. She was a perfect mother, always kind and caring, looking out for my needs. In looking back through my “archive” of personal documents I can see that my first written word was mother.

My hometown, Coffeyville, was one of twelve townships in Montgomery County, a flat, grassy patch of southeast Kansas. The southern edge of town stopped only a few miles short of the Oklahoma border. On the east side of town, a winding 270-mile river called the Verdigris, one of the principal tributaries of the Arkansas River, flowed lazily to the south. My hometown is famous for one event. It’s the place where the Dalton gang met its ignominious end. In 1892, Coffeyville possessed two banks, making it a tempting target for ambitious robbers. On October 5, five members of the infamous Oklahoma-based gang arrived in town, attempting to hold up the two banks simultaneously. It was a bold plan, but foolish; the unnecessary dispersal of the robbers’ numbers allowed a mob of Coffeyville residents to gather at a local hardware store, borrow its firearms, and dispatch the thieves. After a twelve-minute shootout, four gang members lay dead, as did four Coffeyville citizens. We children grew up hearing the thrilling stories of the townsfolk who resolutely defended their prairie boomtown from these villainous interlopers. I remember listening to a bewhiskered veteran of the gunfight, a garrulous man who regaled children about how he had been “wounded” (pronounced in such a way that it rhymed with “pounded”) in the legendary battle.

My parents’ house stood in the midst of an expanding urban oasis. The home usually smelled of flowers and asparagus, thanks to a large patch of each in the backyard. The noise of frolicking children echoed up and down the short road. Our neighbors, Russell and Effie Tongiers, boasted a large house with nine children. The Tongierses’ house came courtesy of Effie’s brother, Walter Johnson, the star pitcher for the Washington Senators and one of the first five players inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

As a child I had dark—nearly black—eyes, exactly like Mom. My hair was straight and light-colored, although it gradually darkened as I aged, and I had large, protruding ears. I was shorter than most boys my age, and as the youngest of three siblings, I tended to draw plenty of attention from my mother. I don’t remember much about my personality, but Mom kept an annotated photograph album that described my misadventures. She noted how I had an uncontrollable fondness for exploring. One photograph depicts me wearing a knit bonnet standing in the center of a dusty trail, surrounded by overgrown weeds. Mom captioned the image, “There’s a long, long trail.” I wanted to be the first to see the end of it. I loved the water, too. When I was six years old, I preferred to don a sailor’s outfit. I wore it as often as possible, an easy accomplishment because Mom also admired it. Once, she wrote, “When you first wore this suit you looked in the mirror and remarked (hands deep in pockets), ‘Now I’m a real boy, ain’t I mother!’ ” In 1924, my parents took me on a visit to California and I saw the Pacific Ocean for the first time. It didn’t take long for me to love those waves. I splashed around in the surf for hours and had to be dragged away from them. My thirst for adventure came from my admiration of my siblings, both of whom took well to the rigors of the Kansas prairie. Louis (my older brother by six years) and Katherine (my older sister by three years) both possessed an unrequited sense of wanderlust. They were quick, clever, loving siblings. It wasn’t hard to be the youngest of the brood; with a smart, attentive older brother and sister, all I had to do was sit back and learn.

However, I liked to do things my own way. First of all, I named myself. I was baptized “Norman Jack Kleiss.” For the first four years of my life, everyone called me Norman. I hated it. I insisted on going by my middle name, Jack. When condescending adults asked me, “How is little Norman?” I set them straight. I huffed, “My name Jack!” (I left out the verb.) By age five, my parents accepted the name change. I was Jack. It became my name, now and forever. Also, I loved to act like a daredevil, and sometimes that backfired on me. One day, when I was three, while visiting my aunt’s farm, I insisted on riding my cousin’s mule. Although Mom and Dad protested, I climbed into the saddle with help from my cousin. Suddenly, as if to prove my stupidity, the mule reared its legs, flinging me violently into the air. As Mom later described it, “We were horrified and fully expected you to be killed.” With a sickening thud, I landed hard on the ground. The mule tromped off, glad to be rid of me, and my parents rushed to my rescue. They feared they would find a broken boy, but amazingly, I stood up and dusted myself off with only a single bruise on my left arm. I had survived my first brush with death. As Mom told it, for the next few days I reprimanded the mule comically, with my minor speech impediment, saying many times, “Bad ol’ ’ule.”

My symptoms of independence often got me into trouble. One of my first memories involved me being tied to a tree at the edge of our property. I must have been four or five years old. One day, my father took me on a short walk from the house to his office. The trip traversed about eight blocks and the busiest thoroughfare in town. This was my first walk with Dad to see what he did for a living, and I loved it. I enjoyed the sights of Coffeyville, the streetcars and buses, the locations of the Dalton gang robbery, and my father’s office. The next day, after Dad left for work, I decided to follow him. I had memorized the route sufficiently, and I said to myself, “Hmm, I’ll just go downtown and see where everyone else goes. They keep busy and I’m left out of all the fun stuff.” Although I had made the trip only once, I crossed the tracks successfully, passed through the intersection, ascended a flight of stairs, and arrived at my father’s office as if I were a regular client. Dad flew into a fury. He dragged me back home, and to teach me a lesson—that I should never travel without an adult—he tied me to a tree. At first, I didn’t seem to get it. Why did Dad immobilize me? I tugged at the ropes, shouting defiantly: “I wish I could pull this tee down!” (At the time, I never pronounced the letter r.) Nobody would help me. I was stuck there for two or three hours until Dad finally released me.

I guess my father’s lesson stuck. I never followed him to work again. However, I’m not sure if he was successful in getting me to stop exploring. As a youngster, I wanted to see more of the world, and no one—not even Mom and Dad—could stop me. None of this is to say I was incorrigible. In fact, I learned the lessons of right and wrong fairly early. One day, my father hired a man to clean the pump attached to our cistern. For some childish reason, I decided I wanted to hear the splash of an object dropped down that hole. When no one was looking, I grabbed the family’s finest silverware and released them, one by one, into the gaping chasm. I giggled when I heard the splash, but my thrill was short-lived. My parents fired our part-time maid, accusing her of stealing the silverware. I felt horribly guilty about it. Six months later, the man returned to clean the cistern’s gutters and recovered the missing silverware. My parents discovered my misdeed and summarily punished me. I learned my lesson. My misbehavior had resulted in a terrible consequence for our maid, who was innocent of the crime for which she was accused. This incident has lingered in my mind for years, a reminder of the definition of “consequences.” Since then, I’ve done my best never to let others suffer for my transgressions.

Religion played an important role in my childhood. Every Sunday, Mom and Dad donned their finest to attend morning services at Coffeyville’s First Methodist Episcopal Church, a stately brick edifice at the northwest corner of Tenth and Elm. After listening to my teachers at Sunday school, I came to believe God routinely intervened in the affairs of humankind. All of the inexplicable occurrences—good or bad—were part of His plan. I imagine this message influenced my outlook on life. I believed that life was a mission. Only after mortals completed their earthly duty could their souls be called to the Kingdom of Heaven. I preferred to believe that God had a special plan for me. I just had to figure out what it was.

At age six, I commenced my public education, heading off to Garfield Elementary School, a small public facility in the center of town. I loved to learn. My first report card contained a healthy mix of M’s, B’s, and E’s, meaning I performed at average or above average in all of my subjects.* During my first term, I was never tardy and I missed only four days due to illness. I also loved to play pranks. In January 1922, on a wintry day, as I waited to enter class, a schoolmate and I hid behind the corner of our building, watching an English teacher approach the door. Without warning, we tossed two well-aimed snowballs at her. The snowballs struck her squarely in the chest, causing her to lose her balance and fall ungracefully, her legs thrashing comically in the air. We had planned to run, but the ludicrous sight of our upended teacher caused us to laugh so hard that we forgot to make a break for it. Eventually, the humiliated proctor righted herself, caught us by the arm, and declared us suspended from first grade for a full week.

The snowball assault was symptomatic of my love of taking risks. As a child, I exhibited no trouble embracing daredevilry. Whenever my friends needed me for some dangerous task, I complied. When playing ball, items sometimes got caught on the roof. As the smallest of my playmates, I was the easiest to hoist atop a neighbor’s house. I volunteered for these missions, rescuing lost toys for friends, performing feats that would have appalled my parents if they had been there to see. Even games of tag came with a violent edge. My brother and I frequently went across the street to play with the Rosebush boys, Kenneth and Robert. Of course, the Coffeyville version of tag differed greatly from the original. At the beginning of the game, we determined who would be “it.” That person stood in the center of the Rosebushes’ backyard while the others ran in a circle around him. Then the “it”-person lit a flash-cracker and dropped it into an old World War I shell casing. Next, he dropped in a tennis ball, so the casing became a cannon. The “it”-person could not move, but he could rotate, waiting for the flash-cracker’s fuse to burn down. When it exploded, the tennis ball shot out like a rocket. If you got hit, it knocked you down. Those were the kinds of games we played.

By today’s standards, cannon-fired tennis balls might seem unusual, but this was par for the course. People didn’t worry much about kids in those days. You either lived, or you didn’t. We grew up hard and fast and learned to look after ourselves. In the summers, my father didn’t mind dropping us off for daylong boat rides in the Verdigris River. My friends and I took lumber from wrecked houses and we built ourselves a scow called the Punkin’ Creek Special, named for one of the tributaries of the Verdigris. Later on, I even built my own boat. Using surplus flooring pilfered from construction sites, I cobbled together a small dinghy. Each morning, Dad hooked the tiny rowboat to the back of his car and drove it up the Verdigris River and dropped me off. All day long, I floated downstream. At about 2:30 in the afternoon, Dad drove along the road, looking for the boat, picking me up wherever I happened to land.

Because we floated for hours without any adult, we learned to look after each other. The crew of the Punkin’ Creek Special consisted of six boys, one girl, and one dog: me, my brother, my sister, the two Rosebush boys, Bill Mitchell, and Jack Isham; the Rosebushes’ dog, an Airedale named Dan, whom I loved dearly, sat near the rudder. It was fun enough, but we learned to share responsibility. Someone always manned the rudder. One of us always kept a lookout for danger. Although we enjoyed fishing and chatting, the experience taught plenty of valuable life lessons: always be alert, always be responsible for your job.

I learned responsibility in others ways, too. My first pennies came from household chores. Dad awarded me an allowance for refueling the kitchen furnace. I hauled coal from the garage about three times per day, receiving one cent per bucket. As I grew older, Dad gave me more demanding work: a nickel for mowing the lawn, a dime for climbing up on the roof and removing unwanted tree limbs, or a quarter for putting more sand underneath the brick walkway. I began my first paid job at age eight. Taking designs I had seen on discarded Singer Sewing Machine kits, I painted pictures of birds on cigar box lids and sold them to neighbors for about fifteen cents apiece. Two years later, I earned ten cents per day by hauling buckets of paint atop towering scaffoldings for building painters. It was dangerous labor, as it required that I remain focused and keep my balance. Working with painters allowed me to learn plenty of curses, words that Dad would never teach me. The painters made the air blue with obscenities whenever one of them goofed up, which was often. As I grew older, work did not get any easier. In junior high, I was a carhop at a local drugstore, earning fifteen cents each evening. My hours were 9 P.M. to midnight. By high school, I worked for the local newspaper, the Coffeyville Journal, delivering newspapers for two dollars per week. I had to get all of my papers to my customers within an hour of printing. If not, I received a “kick,” a nickel reduction in pay for each customer who complained. Typically, I suffered one kick per week, usually caused by the last house on the route. In short, money came hard, and regular pay was never guaranteed.

A Kansas childhood meant growing up with guns. Coffeyville residents took their reputation for frontier justice seriously, and they imparted children with the skill to shoot. My aunt (on my father’s side), Helen Ruthrauff, was the women’s shotgun champion of Kansas, and she gave me some valuable pointers. However, I learned most of my marksmanship lessons from my neighbor Earl Alfonso Rosebush, the father of my two playmates. Although Mr. Rosebush was not a competitive marksman, I considered him one of the best shots I had ever seen. Rosebush always carried a revolver. One day, I accompanied him for a ride in his Chandler automobile. As the car whizzed along a sandy road, churning up grit, Rosebush sighted a jackrabbit as it bolted from the brush. Without pause, he drew his pistol, rested his wrist on the side of the door, and fired. In one blast, he shot the rabbit dead. He brought the car to a halt and told me to go fetch it. (He intended to bring it home for dinner.) This was an incredible thing: Rosebush had hit a moving target from a speeding vehicle. He saw the astonished look on my face. He asked, “Do you wanna learn to shoot like that?” I nodded. He took me under his wing and let me practice with his pistol. I prefer to believe that his instructions contributed to my excellent aim as a dive bomber pilot. After all, leading a jackrabbit is not too different than leading a ship. For both, the shooter must aim for where the target is going to be, not where it is.

In general, I lived a pleasant childhood, as agreeable as the Kansas prairie could be for a young boy. However, childhood brought sad times as well. Nothing prepared me for my family’s greatest tragedy, the untimely loss of my mother on February 14, 1929. Mom died from the effects of stomach cancer. It had been a long, troublesome illness. The cancer had left her bedridden for more than a year, and it put such a strain on Dad that he had to separate the family temporarily. He took Mom to Johns Hopkins Teaching Hospital in Baltimore to find some form of relief, and accordingly, he sent me to live with my uncle, William Coleman, in Lincoln, Illinois.

My stay in Lincoln had the potential to change my life aspirations. Uncle William was a larger-than-life character. After marrying Mom’s sister, Nellie Dunham, Uncle William served as a surgeon in the First World War. He had one son, Walter Dan Coleman, and he hoped that Cousin Walter might follow in his footsteps and become a physician, too. Instead, in 1929, Walter chose to accept an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy. With his son shying away from medicine, Uncle William attempted to impart his passion for medical knowledge upon me. I liked the idea and I spent many months following my uncle to surgeries and house calls. I loved watching him work in his white suit, taking care of various maladies. Mostly I enjoyed his care for babies, as he tried to deduce their ailments even though they could not speak. My interest in medicine impressed Uncle William to the point that he promised financial support if I ever declared my intent to go to medical school. For a time, I was certain I wanted to be a doctor.

In the winter of 1929, I returned to Coffeyville for my mother’s funeral, a terribly sad affair. Saying goodbye to Mom was one of the hardest ordeals in my very long life. Although my family surrounded me, I felt cold and alone, detached from emotion in a way I had never felt before. The only solace was religion. According to the scriptures, Mom was in heaven—no longer in pain—and sitting at the side of her maker. That thought gave me some sense of closure. However, I must have been visibly upset. To ease my melancholy, the Tongierses bought me a small dog named Ginger. I appreciated the gesture, but she wasn’t the greatest dog. After a few months, Ginger ran away. It seemed as if I was destined to bear my sadness alone during that gloomy winter.

I returned to ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Frontispiece

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword by Jill Kleiss

- Introduction by Norman Jack Kleiss

- Maps

- Chapter 1 Kansas Childhood, 1916–1932

- Chapter 2 The Lure of Flight, 1932–1934

- Chapter 3 Midshipman, 1934–1938

- Chapter 4 Finding Love, 1938–1939

- Chapter 5 The Navy’s Surface Fleet, 1939–1940

- Chapter 6 Flight Training, 1940–1941

- Chapter 7 Scouting Squadron Six, Part 1, May–June 1941

- Chapter 8 Scouting Squadron Six, Part 2, June–November 1941

- Chapter 9 The Pacific War Begins, November 1941–January 1942

- Chapter 10 The Battle of the Marshall Islands, February 1942

- Chapter 11 Wake and Marcus Islands, February–March 1942

- Chapter 12 Return to the Central Pacific, March–June 1942

- Chapter 13 The Battle of Midway, Part 1, The Morning Attack, June 4, 1942

- Chapter 14 The Battle of Midway, Part 2, The Afternoon Attack, June 4, 1942

- Chapter 15 The Battle of Midway, Part 3, June 5 and 6, 1942

- Chapter 16 Return to the States, June–October 1942

- Chapter 17 Flight Instructor, 1942–1945

- Chapter 18 My Life after the Second World War, 1946–1976

- Chapter 19 Remembering Midway, 1976–2016

- Afterword by Timothy J. Orr

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix: Roster, Scouting Squadron Six, May 1941 to June 1942

- Glossary of Military Acronyms

- Index

- Photo Section

- About the Authors

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Never Call Me a Hero by N. Jack Kleiss,Timothy Orr,Laura Orr in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Biografías militares. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.