We had barely drifted out of Alexandria’s harbor when I heard my father cry, “Ragaouna Masr”—Take us back to Cairo.

It became his personal refrain, his anthem aboard the old converted cargo ship that rocked so violently as it crossed the Mediterranean that we couldn’t bear to stay even for a moment in our inexpensive lower berths, but would slip upstairs to the relative comfort of the upper deck. There, seated on high-backed canvas chairs aligned in straight rows, we’d spend our days and nights, unable to sleep or eat or do much more than try to look back at what we had left behind, or ahead to what awaited us.

Both suddenly seemed blurry.

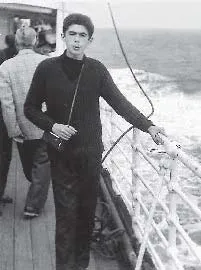

Past and future looked as vague and out of focus as the lone photograph that survives of my father and me aboard the Massalia. There we are, huddled on the upper deck, while behind us, dozens of people sit silently watching the sea. It is like a scene from a cruise ship ad gone awry: none of the passengers seem happy, least of all my father. In his dark felt hat, jacket, and tie, he is dressed far too formally for a sea crossing. He stares straight ahead at the camera, looking sullen and worn and, for the first time, old. I share his melancholy. My head is lowered, my eyes are downcast, and if it is possible for a six-year-old girl to feel defeated, then I look as if I, too, have lost my purpose. Perched against his shoulder, I am holding on to him, in need of his protection even now that he may be incapable of giving it.

Leon and Loulou on the Massalia.

It was my brother who snapped the smudgy image in March 1963, using a cheap portable camera.

My father talked obsessively of Malaka Nazli, as if expecting me to grasp all we had lost. After months of frenzied activity, there was nothing left to do. Nothing except to sit back on our deck chairs, and gauge how it had all come to this—decades in the life of a family, reduced to two dank cabins situated too close to the roaring engines of a small unsteady boat, along with the twenty-six suitcases that contained all their worldly belongings.

“Ragaouna Masr,” my father kept shouting. He had lost all inhibitions, and for a man whose life had exemplified elegance and propriety, any sense of decorum seemed gone. He would cry out when he sat alone, and he’d cry in front of other passengers, when we were with him and when we weren’t, inside the privacy of our lower berths and out in the open air. Oddly, no one seemed to mind—or even to find it strange—the sight of this irate old man, at times yelling, at times softly moaning, Take us back to Cairo. He was only saying what they felt in their hearts.

It was at that moment, as the Massalia bobbed up and down on waters as green as my father’s eyes, that I realized how different he looked. I had first noticed the change, a resignation in the way that he drank his beer, ever so slowly, at the café in Alexandria. The jauntiness and self-confidence that were such an intrinsic part of his persona were gone.

It was all so disorienting, as if the man I called my father was an impostor—a desperate stranger I had never met before.

My father wasn’t fifty-five, as his exit papers said; he was sixty-two or sixty-three and looked and felt even older as our ship set sail. He wondered, as he experienced the rush of pain that came and went, came and went, in his hip and thigh, how he was going to begin anew, find work, and support a wife and four children, including a little girl who clung to him for dear life.

As the Massalia chugged along the Mediterranean, stopping first in Greece, then Italy, I had virtually no dealings with Suzette. My sister kept to herself, unwilling to wallow in the collective despair. Unlike my father, she felt nothing but relief as the boat edged out of Alexandria. Egypt had been a nightmare, even before her arrest and the furor over her conduct. The country that my father already missed so much, that he cried to be allowed to enter again, didn’t exist anymore as far as my sister was concerned, and hadn’t for years.

Free at last, she relished the idea of a future in the West without the restrictions and stifling mores of the Levant.

Meanwhile, my oldest brother, César, constantly seasick, found he couldn’t think clearly. He didn’t share my sister’s boundless optimism—or my father’s boundless despair—but remained suspended somewhere between the two. He kept running upstairs for fresh air, unable to stand the claustrophobia of our lower cabins and the constant thud-thud-thud-thud of the engines, and the waves crashing against the porthole. I never seemed to see Isaac or my mom.

César on the deck of the Massalia.

Late one evening, we drifted into Genoa, the last port of call before France. There at the docks, waiting for us, was Salomone, the glamorous cousin from Milan I had heard so much about. As tall as my father, elegant and exquisitely dressed, he was an imposing figure. Everyone in my family—my mother in particular—seemed thrilled to see him.

It was their first reunion since Salomone had left Egypt fourteen years earlier, in 1949. Married and a father of three, he was presiding over a growing import-export concern, and his business stretched from Europe to Africa. Yet his home base was still Milan, the city of his youth and memories. Ghosts of his parents and little sister lurked in every corner. Salomone lived in an apartment close to the Duomo, where the family had lived shortly after he was born, and not far from the square where Mussolini had founded the Fascist Party. This was the school Violetta had attended and where she’d written her first poems, and over here was the prison where she and his parents had been held. And there, of course, the station where they had boarded the train to Auschwitz at dawn, never to return.

We followed Salomone to a nearby café, popular with sailors. The only bit of cheer within the stark, poorly lit interior was the overabundance of Easter decorations. All around the eatery, I could see displays of Easter eggs. They hung alluringly from ceilings or were stacked side by side along high shelves, dazzling in their gold and silver foil casings, and artfully tied with large satin ribbons. The eggs were made entirely of chocolate, and several were at least a foot tall.

I found myself obsessing over what lay beneath all the layers, and left the table to inspect them more closely. My parents and cousin were so deep in conversation, they seemed oblivious to my comings and goings: they were busy reminiscing about their years together at Malaka Nazli, Salomone and my father, along with my grandmother Zarifa, and at the end, the lovely young stranger who joined their household, my mother, Edith.

But they also flashed forward to our family’s current plight and what we were going to do now. My cousin had tried to arrange for Suzette to live with him and his family. He had gone to see high-ranking government officials to obtain the proper papers, to no avail. The authorities wouldn’t allow my nineteen-year-old sister to remain in Italy. As far as the rest of our family, while Milan was appealing because of our bond with and love for Salomone, it simply wasn’t an option. There were many Egyptian Jews who had settled in Italy, but most were able to claim Italian citizenship, however tenuous. They wangled their way into Rome or Milan by stating they were “half-Italian,” brandishing a wife’s Italian passport, or a parent’s or grandparent’s. We were stateless, which meant our movements were severely limited.

We only had permission to go to France, where we would be allowed to stay a few months until we found a permanent refuge.

As I continued my tour of the café, eyeing the chocolate eggs, I looked up to see Salomone towering over me. He was, like my father, a man of few words. He asked me which one I wanted. The café, which had felt melancholy and dim, suddenly seemed flooded with light. I wasn’t sure what to do. I knew that I couldn’t point to the largest, most extravagant egg, but I didn’t think I had to settle for the smallest egg either. I stood there, incapable of making a decision.

Salomone finally extended his long arm to the ceiling, plucked an egg from a top shelf, and handed it to me. It was elegant and massive, wrapped in silver.

“Ça va?” he asked me.

I nodded, dazed by his gesture, and returned to the table, brandishing my Easter egg like a trophy. When it was time to return to the boat, everyone rose, my father and my cousin embraced. Salomone lingered briefly by my mother, hugged her tenderly, waved to us, and climbed into his car and drove away.

As we walked, I began to unwrap the egg. I had to peel off layers of foil, tissue paper, and bits of ribbon, until at last I saw the outline of an immense globe-shaped milk chocolate. I broke off a piece. The egg was hollow inside, and I realized there was a gift within the gift—that deep inside the Easter egg, a prize had been stashed away. My hands finally retrieved a cellophane pouch containing a pair of golden earrings, small and simple and beautiful.

“Tu crois que c’est de l’or?” I asked my father; Do you think it is real gold? My brothers burst out laughing, but my father wouldn’t say yes or no. I stuffed the earrings in my pocket and continued walking. We could hear the Greek crew amiably shouting to everyone to hurry up and come aboard, lending passengers like my dad a hand walking the rickety gangplank.

At last, the boat floated into Marseilles. Exhausted from the voyage, we had no means to check into a hotel but hurried, our twenty-six suitcases in tow, to catch an overnight train to Paris. César left us to explore the station. He wore his prized black leather jacket, a blouson noir, one of his last purchases from Egypt. It was to be his passport to the stylish world of the French.

As he wandered aimlessly, he suddenly found himself flanked by two plainclothes officers. They pushed him against a wall and began to frisk him. They had noticed him roaming the station, dressed all in black, and had mistaken him for a “Blouson Noir,” one of the North African gang members who were terrorizing France and were involved in protest actions against the unpopular war in Algeria. Any young man who fit a certain physical and ethnic profile fell under immediate suspicion, and my oldest brother, with his classic Middle Eastern good looks—dark curly hair, brown eyes, fair skin, and black leather garb—could easily pass for an Algerian immigrant.

Pointing to an unmarked car, the officers asked him to accompany them for questioning. His eyes widening, César shook his head no, no. He was certain that if he obeyed the men and followed them into the car, he would never see us again. Trying to gather his wits, my brother explained that he was indeed a refugee from North Africa—not Algeria but Egypt. He urged the officers to locate our parents, who were in another part of the station. “Mon père est là-bas, avec ma mère et ma famille,” he pleaded; My dad is over there, with my mom and the rest of my family. But the officers seemed uninterested in finding any of us, and César had no choice but to keep trying to talk his way out of his nightmare.

He didn’t belong to any gang, my sixteen-year-old brother assured them again and again. His outfit, his leather blouson, was simply a nice jacket he had picked up in Cairo. They still cast a cold eye on his professions of innocence. After peppering him with dozens more questions, they reluctantly let him go, and sped away in their unmarked car.

My brother, still shivering under his blouson noir, joined us as we boarded the train to Paris. He didn’t breathe a word about what had happened.

He had been in France exactly one hour.

I fell asleep by my father’s side, clutching what was left of my Italian chocolate egg. Sometime in the middle of the night, somewhere in the middle of France, the train came to a sudden halt. The rail workers were on strike, we were told. We were caught in one of the country’s legendary union actions. There was no choice but to remain in the darkened locomotive.

The Marseilles-to-Paris journey had turned into a frightening web of deserted open rail yards, long dreary waits, and trains that went nowhere. We were exhausted and cold, and we could only wonder at our first taste of life outside Cairo.

AT LAST, THE ENDLESS night journey across France came to an end. We were in Paris and it was morning and there was light.

From the station, my father telephoned a contact at the relief agency helping the flow of Jewish refugees from the Arab countries. We were listed as “stateless” on all our travel documents, and we didn’t know our final destination. Dad anxiously inquired what was in store for us now that we had left Egypt. He had an exhausted family on his hands, and he wasn’t well himself. There was also a six-year-old child, “une petite qui est très fragile,” he informed the agency official, his voice nearly breaking from tension and fatigue. We were told to report to our temporary lodgings in the tenth arrondissement, at the Violet Hotel.

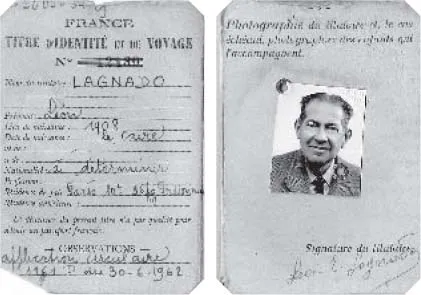

Leon’s identification papers, Paris, 1963. This nationality was “a déterminer”—to be determined.

I liked the sound of it. I expected a building of lavender walls and lilac floors rising beneath a mauve-tinted sky. Instead, we found ourselves staring at a dingy and singularly charmless establishment that was all gray and discolored broken bricks and stone. Our rooms were situated on an alleyway known as the passage Violet, a narrow lane of fabric stores, fur workshops, and small factories that made buttons and dolls. I vainly scanned the little street for a speck of purple, but there was none that I could see.

It was even worse inside.

Home was now a couple of rooms containing six beds and the twenty-six assorted suitcases that had followed us from the station. Because of their bulk and size, they turned us into virtual prisoners of our hotel, taking up so much space we could barely walk without stubbing our toes or bumping into one another.

Our rooms were on the second floor of an annex that was, if possible, even more decrepit than the main hotel building. We had to climb a rickety flight of stairs, a painful and awkward undertaking for my father.

It was in Paris that Papa’s cane, packed as an afterthought when we left, made a surprise reappearance. I had rarely seen him use it in Cairo, where years in the care of top doctors had enabled my father to attain a fair degree of mobility and independence. But he now needed it to get upstairs, and then to get down again.

We didn’t bother to open any luggage. It wasn’t clear if it was because we were too depressed, or because it would have been pointless. The bags that my older sister had packed with so much excitement, cramming them with her new wardrobe, were now a source of exasperation. Why can’t we unpack? she kept asking my father. Why do we have to keep the suitcases locked as if we were about to flee again?

He shrugged as if to say that at nineteen going on twenty, she was old enough to figure it out. Paris was only a stop on a long, as-yet-unfinished journey. When we arrived in France, at the end of March 1963, we were still in the same limbo status indicated on our luggage tags from Cairo, “Famille Lagnado,” but no discernible address.

Around the corner was the rue du Faubourg Poissonière, a narrow, windy street that looked exactly like every other narrow, windy Parisian street, with one major difference. Poissonière and the area around it had catered to generations of Jewish refugees who had fled any number of countries that no longer wanted them.

The cultural and historical landscape had changed over the years, but the story of exile and persecution was numbingly the same.

France had historically been a transit point for refugees, a role it was re-creating assiduously now with the flow of Jewish families like my own. In the 1930s and ’40s, Jews fleeing the Nazis converged on this small strip near our hotel, some opening ateliers and plying the fur trade. Later, in the 1950s and 1960s, Jews seeking to escape the violence and turmoil in the Middle East unleashed by the creation of Israel descended on the faubourg. The area attracted immigrants from Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, and Libya who were housed in the shabby residential hotels that did a booming busin...