Who were the Native Americans? The Spanish, French, and English explorers were perplexed by that question. Their first assumption that the natives were Chinese was soon abandoned; the natives obviously were not European and did not seem to be African either. The explorers could not think of any other possibilities. William Strachey spoke for them in 1612 in his Historie of Travell into Virginia Britania: “It were not perhappes too curyous a thing to demaund, how these people might come first, and from whome, and whence, having no entercourse with Africa, Asia nor Europe, and considering the whole world, so many years, by all knowledg receaved, was supposed to be only conteyned and circumscrybed in the discovered and travelled Bowndes of those three.”

The Indian societies he saw, Strachey would have been astonished to learn, were formed by thousands of years of migration, splitting apart, rejoining, exchanging mates, settling, and adapting—essentially the same process that shaped European lives and culture. Just as Europeans were products of the migrations of western Asians, so the Native Americans were descendants of migrants from eastern Asia. And just as the Europeans’ languages give a view of their history, so American Indians’ languages illustrate their background.

The first Indians the Spaniards encountered in what they named La Florida spoke dialects of a language known as Muskhogean. It was one of 583 languages that have so far been identified as spoken by natives in North and South America. Linguists trace it back to a tongue they call Amerind. Linguistic evidence points toward northeastern Asia as their “origin.” What the spread of language indicates has now been confirmed by genetic studies. Together they suggest that ancestors of the American Indians probably began crossing to North America roughly 30,000 years ago. Climatologists now believe that from about 60,000 years ago, Asia and North America were joined at what is now the Bering Strait and archaeologists have found evidence of human settlements in northeastern Siberia from about 40,000 years ago. So it was possible for humans and animals to walk across a land bridge, which geologists call Beringia. They began to do so because, although much of North America was covered by huge glaciers and sheets of ice, parts of Alaska enjoyed a relatively mild climate. Even in the coldest times, there was a corridor of relatively open countryside that channeled movement of animals and men to the south. Then, about 10,000 years ago, with the coming of what geologists term the Holocene, a warmer epoch, so much ice melted that the sea rose as much as 120 meters and submerged the land bridge. Those people who had already made the passage from Asia profited from the melting of the vast sheets of ice to move inland and further south. By about 14,000 years ago, some had reached Patagonia and others had spread over both continents.

After their arrival in the New World, the speakers of Amerind spread out across almost the whole of North and South America. Pockets of other languages remained in the American Southwest and the Canadian Northwest. These were derivatives of an Old World language now called Na-Dene and were spoken in the far north of the continent where what is known as Eskimo-Aleut was the common tongue. Then, for thousands of years as families and small clans moved apart from one another, they acquired different habits, adapted to different environments, and made changes in the way they spoke. We can see how this process works by delving back into the past of our own language. Shakespeare’s English is intelligible to us although it contains expressions we no longer understand. Middle English, spoken a few centuries earlier, is arcane. Farther back and farther away, English’s close cousins—Spanish, Italian, French, and Portuguese—although sharing some vocabulary and much syntax and grammar, were already largely foreign. If we move yet farther afield to languages in our same Indo-European family, Russian, Persian, Greek, Armenian, and Sanskrit appear almost totally alien. So it was with the Indian languages. Over thousands of years and a large stretch of geography, each society elaborated from the common ancestor its own way of thought and speech.

When the French explorer Sammuel Champlain landed on the Saint Lawrence in 1608, he encountered a people speaking Algonquian, a language related to the language spoken far to the south in Virginia. What that seemingly unlikely fact tells us is that the two groups must have originally been one people; as one or both migrated, they first became neighbors and finally strangers, just the way our European ancestors did.

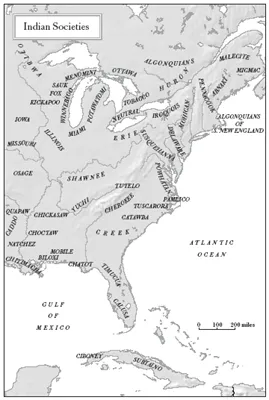

The largest, most sophisticated, and most warlike of the northeastern Indian societies were speakers of Iroquoian. When the explorers first encountered them, they had divided into five nations but were still linked by a confederation which they called Haudenosaunee (Iroquoian for “the Long House”). The 6,000 or so members of the confederation were tribes known as the Kaniengebaga (or, as their enemies called them, the Mohawks), the Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Senecas. Related to them and speaking dialects of Iroquois were the Cherokee and Tuscarora, who had earlier migrated southward.

Another family of languages was Siouan, spoken by peoples who dominated the Piedmont southward from Maryland. They included the Catawba, Saponi, Tutelo, Occaneechee, and Cheraw of the Carolinas and the Creek of what became Georgia, as well as scores of smaller, now mainly forgotten groups.

A fourth collection of societies, the North American native people the Spaniards first knew, spoke varieties of Muskhogean and inhabited the Gulf coastal region from Georgia to the Mississippi.

Speakers of these four groups of languages, the Native Americans living east of the Mississippi, probably numbered about 2 million on the eve of first contact with Europeans.

As they spread out over North America, the Indians developed such distinctive characteristics as to seem alien to one another, just as the European and African nations did. Frequently clashing with one another as they sought to defend or enlarge territories, each emphasized its uniqueness. Many of the Indian names for themselves meant “the people” or “the real people”; that is, each group asserted that it was fundamentally unlike its neighbors, who were not “real” people. As the Spanish, French, and English invaders quickly realized, these differences had given rise to bitter and long-standing hostilities that made it virtually impossible for the Indians to combine against Europeans. With their eyes firmly fixed on their neighbors, time after time, group after group, Indians would welcome foreign invaders and attempt to use them in local struggles. This was also the experience during the European conquest of Africa and Asia: European military force often provided only “stiffening” to the mainly indigenous armies that established European rule. Moreover, individual tribal societies could never match the manpower that national consolidation in Europe gave Britain, France, and Spain. Fragmented as the vast areas of Africa, Asia, and the Americas in fact were, each was outnumbered as well as outgunned by the invaders.

While diverse and often mutually hostile, the societies also retained many common features. Since no Native American society north of Mexico produced or bequeathed to us its own record, we glimpse them only in the blurred picture presented by European visitors. None of the first Europeans, of course, spoke native languages; when a few did learn some dialect, they rarely thought it worthwhile to try to capture the thoughts, fears, or hopes of any Native Americans.

The most sophisticated of the observers, the Jesuit priests in the areas controlled by Spain, learned more but also were more hostile to Indian culture. A striking example is given in the account of the Jesuit missionary Juan Nentuig:

The priests considered dances, feasts, and even athletic competitions almost as bad as sex: to them all ceremonies except their own were satanic. Even an outburst of joy when rain fell on the parched desert seemed sinful.

Most of those who could have told us much about the Indians were simply not interested. Perhaps the longest and most intimate contact between a group of Europeans and a Native American was at Plymouth. There, in 1620, William Bradford met a man he called Squanto. This man had visited England and had, apparently, a considerable command of English. As Bradford describes it, Squanto had a warm and friendly relationship with the Pilgrims. By teaching them how to plant corn and how to survive in cold New England, he quite literally saved their lives; and he stayed with them for over thirty years—until about 1653. But Bradford, in his otherwise instructive writings, gives no hint of what Squanto might have related about his people. Obviously, Bradford did not care.

Remarkably different—indeed, for the late seventeenth century, probably uniquely different—was the Virginia colonist Robert Beverley. He wrote, “I have been at several of the Indian towns and conversed with some of the most sensible of them in that country, but I could learn little from them, it being reckoned sacrilege to divulge the principles of their religion.” So Beverley did not sit passively by. He took an opportunity to break into a quioccasan (shrine) to see what it contained. He found it almost as bare as a Puritan church, but he examined an ossuary and an idol (variously known as Okee, Quioccos, or Kiwasa). From other Indians he had learned that each town had its own shrine. Unsatisfied, Beverley sought out a particularly intelligent Indian, and “seating him close by a large fire, and giving him plenty of strong cider which I hoped would make him good company and openhearted,” plied him with questions. The response he got was remarkable:

I know of no other early account in which a white colonist tried so carefully to understand Indian belief or, indeed, other aspects of Indian life. Much of what we know of Indian life comes from later centuries. But by then, Indian societies and culture had been violently transformed. The older people, who were the carriers and disseminators of tradition, died before they could perpetuate their lore; societies imploded and mingled with survivors of alien groups so that the sense of being “a people” withered. And the whites, having filled the lands with their own kind, moved ever westward. It is what white people later saw or heard about in the West that, largely unconsciously, we see as “Indian” in our mind’s eye. What our more recent ancestors learned about the nineteenth-century nomads of the Great Plains has been further programmed in our minds by the cinema. Sitting Bull, Geronimo, and Crazy Horse are the quintessential Indian warriors, flashing across the screen on their Spanish ponies, hot after buffalo or white settlers. Even after stripping away the stereotype, we can see that the actual way of life of the hunters of the Great Plains was very different from that of the farmers met by the colonists on the Atlantic coast in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. So I begin with a basic feature of their lives, agriculture.

Native Americans began the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture at roughly the same time as Old World farmers but faced a more difficult task. Some of the plant species with which they experimented, notably the potato (Solanum tuberosum), of the nightshade family, contained poisons that had to be extracted before the plants could be eaten. It must have taken generations of experimentation and selective cultivation to turn the potato into a vegetable that was safe to eat. All the Europeans who met the Indians were impressed by their knowledge of edible and medicinal plants. In plants they were relatively rich, but in animals they were poor. They had no animals comparable to the goats, sheep, horses, donkeys, wild asses, camels, or elephants of the Old World. Their only domesticated animal was the dog.

The most distinctive Indian food crop, corn (in Algonquian, maize), was first domesticated in Mexico about 3000 B.C.E. and slowly made its way all over both North and South America, growing in an astonishing variety of climates and altitudes. The English marveled at its fecundity: it produced a far higher yield than European food grains. In 1587, in “A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Viriginia,” Thomas Hariot exclaimed, “It is a graine of marvellous great increase: of a thousand, fifteene hundred, and some two thousand folde.” For the East Coast Indians, corn was life: they pounded it to make bread, boiled it to make gruel, and treated it with wood ash to make hominy.

They also ate a variety of tubers, gourds, pumpkins, and squashes (in the Narragansett dialect of Algonquian, askútasquash); they demonstrated their feel for agronomy by planting the lima bean and the kidney bean in the same fields with squash and corn to enrich the soil. And just as they combined these plants in the fields, they also did in the cooking pot, making mixtures of vegetables like succotash (Narragansett, msiquatash). Farther north, Indians harvested the misnamed “wild rice” (Zizania aquatica) from marshes and ponds. Wild rice had the great advantages of being highly nutritious, growing in very cold areas, and being sown simply by scattering some of each crop back into the water.

Having no draft animals, Indians did not use the plow. Neither did they have iron with which to make alternative implements. Their common tool was a pointed stick with which they punched in the earth holes into which seeds were dropped; they weeded furrows with a sort of hoe and dug with a tool comparable to a spade. With these wooden tools, it was easy to plant around trees or stumps, so although they cleared considerable stretches of agricultural land, much of their produce came from wooded terrain. Rather than trying to “fight” the trees as the white colonists would do, the Indians made a virtue out of forested land: they had learned that some shade made planting easier because the soil remained moist and soft. As they taught the Pilgrims, they fertilized land (and got rid of weeds) by burning brush and by burying fish heads in the hillocks in which they placed seed. Like contemporary European farmers, they let exhausted fields lie fallow temporarily.

Among the East Coast Indians, as among many tribal peoples, agriculture was primarily woman’s work. While the women planted, weeded, harvested, and processed vegetables, the men hunted and fished. Wild turkey, deer, bear, and a variety of smaller animals they found in the forests; and beavers, otters, and fish from the rivers provided a high-protein, nutritious, and abundant diet.

It followed that Indians were generally healthy. As Helen C. Rountree and Thomas E. Davidson comment, “Indian people of both sexes were healthier than early seventeenth century English people…[who] were almost continually ailing: their diet was poor in fruits and vegetables for most of the year.” Indian men, at about 5 feet 7½ inches, were taller than Englishmen by an average of 1 inch; Indian women on average were over 2 inches taller than Englishwomen. The early English visitors and colonists marveled at the size and strength of the Indians. For example, William Strachey described a meeting in what became Maryland where “inhabite a people called the Sasquesahonougs…. Such great and well proportioned men are seldome seene, for they seemed like Gyantes to the English [with voices]…sounding from them (as yt were) a great voyce in a vault or caue as an Eccoe.”

Along the Saint Lawrence, Champlain similarly found all the people

Particularly striking to the early observers was the strength of the Indians and their skill with their primitive weapons. George Percy described a test of the Indians’ strength and skill with a bow and arrow in these words:

Even toward the end of the seventeenth century, when Indians had suffered much from the effects of imported disease and alcohol, Robert Beverley waxed lyrical when he described Indians who, he said, have the

After years of travel among Indians in the Carolinas around 1700, John Lawson found that women’s “Breaths are as sweet as the Air they breathe in, and the Woman seems to be of that tender Composition, as if they were design’d rather for the Bed then Bondage.”

About men, the opinions were less lyrical. When Thomas Jefferson circulated the manuscript of his Notes on the State of Virginia, he received a comment by a French naturalist, the comte de Buffon, that although the Indians are generally larger and taller than Englishmen, “their organs of generation are smaller a...