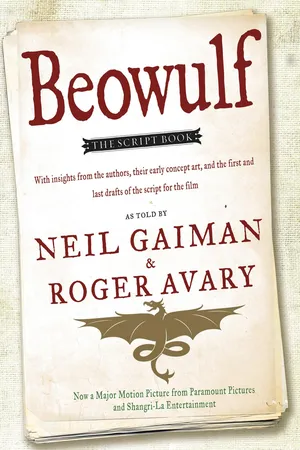

We’ve included in this book both our first draft and our final shooting script. We wanted to show the circuitous path a screenplay takes towards getting made, and to perhaps put the changes that come about over the course of development into some kind of context. So for this foreword I’ve chosen to tell our story of getting the film produced, rather than to analyze the work itself. I figured it would at very least be more entertaining to read.

The script for Beowulf was written quickly, under a palapa in a Mexican quinta I obtained for the writing process, knocking out a first draft in just under two weeks. However, the process of getting the film made took Neil Gaiman and I ten years together, and for me a total of twenty-five years from gestation to completion. During our development of this script, the Internet sprang from the mists, and our computers went from early Apple Powerbook 120’s to screaming Dual Core MacBooks and 2GHz Dells, spanning Final Draft 2 to Final Draft 7. Collaboration isn’t easy, but when it works, and the muse comes to you both at the same time, it’s a pretty hot threesome. Beowulf was like that. Through it all, Neil and I have become close lifelong friends, and I love few the way I love him.

My fate was sealed for me by Lorenzo DiBonaventura, the studio honcho then running Warner Bros., who had me into his office because he loved the “manic energy” in my film Killing Zoe. He repeated his favorite scene to me several times—Julie Delpy being thrown naked and wet out of a hotel room and into a hallway—laughing with an odd nostalgia at how ludicrously insane and unpredictable the movie was. Then, quite to my surprise and delight, he looked me in the eye and said, “We’re making a movie with you, we just need to figure out which one. I’m just gonna rattle off titles, and when you like the sound of one, stop me.”

I thought to myself that this was probably the best kind of situation to be in. I sat back, and readied myself for the barrage.

“Sergeant Rock.” Wow. What a way to begin. “—And it’s written by John Milius.”

“Go on.” I could barely contain my excitement. I had somehow wandered into the treasury. He went on to list several titles, some awesome sounding, some dreadful sounding. I went through the list, “yes, no, yes, no, maybe, that sounds interesting, not for me, yes, no…”

Then, Lorenzo casually mentioned a title that cleared the slate of competitors: “Sandman.”

“Sandman?” I questioned. You mean, “Sandman Sandman?”

“Yes.” He jumped up and walked over to a large bureau and opened it up.

“Not…Neil Gaiman’s Sandman?” And in that moment he pulled out two little statues. One was of Dream, the other of Death. I literally stood up. Unable to contain myself, I gushed to Lorenzo about Neil’s work, pronouncing my love of it. I was immediately attached to the film.

I had been introduced to Sandman in 1989, while working in the mailroom of D’Arcy Masius Benton & Bowles—the advertising agency. I had taken the job because it was next to the attorney Quentin Tarantino and I were using to put together the limited partnership paperwork for True Romance. I would literally shuffle mail in the mornings, load the Coke machines, and slip out for hours at a time to sit in the office building next door and prepare budgets and schedules and partnership documents. But months passed during that process, and many of my hours were spent with the ad people, sorting their mail and loading their Coke machines.

One of the executives had DC Comics delivered to him, probably for the purposes of placing ads. He never wanted them, so I ended up getting them—and so over those months, I read the serialized version of Sandman: The Doll’s House.

It was like having a third eye open in my forehead. As I read them, I imagined the movie in my head—widescreen. Johnny Depp as Dream. Fairuza Balk as Death. I would subcontract Jan Svankmajer or the Brothers Quay to animate the transitions from the Dream realm into our own world, so as to simulate the graphic style of Dave McKean’s covers. It would be a glorious and magnificent epic.

A year and a half after my meeting with Lorenzo, I politely left the production, not wanting to be the guy who ruined the Sandman film adaptation. I simply couldn’t imagine the Lord of Dreaming throwing a punch. Just because it looked like Batman at first glance didn’t mean that it was Batman. But Jon Peters, the “savant” producer Warners had attached to the project, couldn’t be dissuaded. I moved on, a year and a half of my life lost to the ether. No more real to me now than the memory of a dream.

In the months that followed I tried to figure out what I would do next. I went through my files of half-finished projects and notes on things I’d always wanted to do. I stumbled upon some notes I had written in 1982, thirteen years before. They were notes on how to turn Beowulf into a feature film.

It was during a high school English lit class that I was first exposed to the epic poem Beowulf. It was the Burton Raffel translation, and its cover depicted, in stained-glass styling, a warrior driving a sword into a fiery red dragon. I was a Dungeons & Dragons geek whose favorite film at the time was Excalibur, and so the passing out of a fantasy book as a credit assignment was like manna from Heaven. I opened it up and read the the first verse:

This book didn’t even resemble the English I knew. Even Raffel’s translation taxed the cognitive capacities of my seventeen-year-old brain. I struggled with it for weeks, well after the assignment passed and I received my C–, until one night I began to read it aloud.

Beowulf was spoken and told around a fire for generations before it was put to parchment by Christian monks, and even now it demands an oral delivery. When spoken, the texture of the writing comes alive, and with breath the arcane nature of the language somehow finds life. But, as a story with an oral tradition, it was no doubt subject to alteration and embellishment. Anyone who’s ever played the game Telephone Operator as a child knows how a simple sentence can transform when passed from one person to the next, and I suspect that Beowulf was subject to...