eBook - ePub

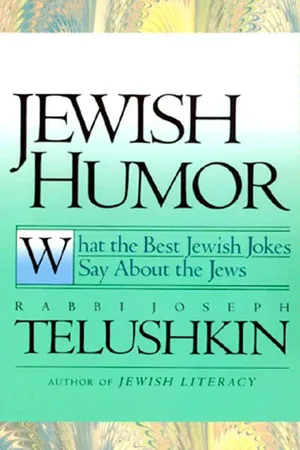

Jewish Humor

Joseph Telushkin

This is a test

Share book

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Jewish Humor

Joseph Telushkin

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Here are more than 100 of the best Jewish jokes you'll ever hear, interspersed with perceptive and persuasive insight into what they can tell us about how Jews see themselves, their families, and their friends, and what they think about money, sex, and success. Rabbi Joseph Telushkin is as celebrated for his wit as for his scholarship, and in this immensely entertaining book, he displays both in equal measure. Stimulating, something stinging, and always very, very funny, Jewish Humor offers a classic portrait of the Jewish collective unconscious.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Jewish Humor an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Jewish Humor by Joseph Telushkin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Jewish Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Jewish Theology1

“Oedipus, Shmedipus, as Long as He Loves His Mother”

The Inescapable Hold of the Jewish Family

Between Parents and Children

Three elderly Jewish women are seated on a bench in Miami Beach, each one bragging about how devoted her son is to her.

The first one says: “My son is so devoted that last year for my birthday he gave me an all-expenses-paid cruise around the world. First class.”

The second one says: “My son is more devoted. For my seventy-fifth birthday last year, he catered an affair for me. And even gave me money to fly down my good friends from New York.”

The third one says: “My son is the most devoted. Three times a week he goes to a psychiatrist. A hundred and twenty dollars an hour he pays him. And what does he speak about the whole time? Me.”

The intense connectedness of the Jewish family is no invention of modern Jewish humor. Its roots go back to the fifth of the Ten Commandments: “Honor your father and mother.”1 Today people take it for granted that religion furthers family closeness; “A family that prays together stays together,” a popular catchphrase of the 1950s declared. But, in fact, it was highly unusual to place respect for parents in a religion’s most basic legal document. New religions generally try to alienate children from parents, fearing that the elders will try to block their offspring from adopting a way of life different from their own. In the United States, many religious cults are notorious for loosening, if not shattering, children’s familial attachments.*

Hostility to parents also characterizes radical, particularly totalitarian, political movements. Both Nazi and Communist societies instructed children to inform party officials of any antigovernment acts or utterances by their parents. In the Soviet Union, well into the 1980s, children who joined the Russian equivalent of the Boy Scouts took an oath to follow in the footsteps of Pavlick Maroza. During the 1930s, twelve-year-old Pavlick informed Communist officials of antigovernment comments made by his father, who was summarily executed. Outraged, the boy’s uncle killed him. For the next half-century, until Gorbachev came to power, Pavlick Maroza was held up to Soviet youth as a model citizen, and statues of him were erected in parks throughout the USSR. One can only imagine the discomfort of parents who, taking their children to a park, were asked to explain whom the statue was depicting. “Pavlick Maroza,” the father (or mother) would answer. “And what did he do, Daddy?” It must have made for some very unpleasant moments.

It is thus quite striking that from its very beginnings, Judaism placed so positive an emphasis on parent-child relations.† Jewish humor, however, is concerned with the down side of this encounter, with what happens when the glorified relationship becomes too intense. Intimations of such an overintensity can be found in the Talmud. Some rabbis placed virtually no limits on filial obligations: “Rabbi Tarfon had a mother for whom, whenever she wished to mount into bed, he would bend down to let her ascend [by stepping on him]; and when she wished to descend, she stepped down upon him. He went and boasted about what he had done in his yeshiva. The others said to him, ‘You have not yet reached half the honor [due her]: has she then thrown a purse before you into the sea without your shaming [or getting angry at] her?’” (Kiddushin 31b).

As if to ensure that children, no matter how well they treated their parents, would still feel guilty, the Talmud relates the story of a righteous gentile, Dama, who was about to conclude the sale of some jewels from which he would derive a 600,000 gold denarii profit. Unfortunately, the key to the case in which the jewels were held was lying beneath his father, and the old man was taking a nap. Dama refused to wake him, “trouble him,” in the words of the Talmud. Of this same Dama, the Talmud relates: “[He] was once wearing a gold embroidered silken cloak and sitting among Roman nobles, when his mother came, tore it off from him, struck him on the head, and spat in his face, yet he did not shame her” (Kiddushin 31a).

So extreme and unending are the demands some talmudic rabbis make of children that one sage, Rabbi Yochanan, declared in despair, “Happy is he who has never seen his parents” (Kiddushin 31b).

In similar fashion, in the story about the three women in Miami Beach, the best way a son can “honor” his mother is by paying a psychiatrist a fortune to speak about her nonstop.

The linking of psychiatry and Jewish mothers is no coincidence. While Jews are overrepresented in medicine in the United States, in no other specialty is this more the case than in psychiatry (477 percent of what would be normal, given Jewish representation in the general population).*

Large-scale Jewish involvement has characterized psychoanalysis, in particular, since its inception. Sigmund Freud selected C. G. Jung to be the first president of the International Psychoanalytic Association because he did not want psychiatry to be dismissed as a “Jewish science” (which the Nazis did anyway) and Jung was the only non-Jew in Freud’s inner circle. “It was only by [Jung’s] appearance on the scene,” Freud claimed in a letter to a friend, “that psychoanalysis escaped the danger of becoming a Jewish national affair.”

Jewish jokes about psychiatry almost invariably involve the family, and they have gone through two phases. In the earliest phase, they dealt with the inability of unsophisticated Eastern European Jews to understand the powerful new insights provided by psychiatry.

A mother is having a very tense relationship with her fourteen-year-old son. Screaming and fighting are constantly going on in the house. She finally brings him to a psychoanalyst. After two sessions, the doctor calls the mother into his office.

“Your son,” he tells her, “has an Oedipus complex.”

“Oedipus, Shmedipus,” the woman answers. “As long as he loves his mother.”

More recent humor assumes that modern Jews are sophisticated about psychology. “Every Jew is either in therapy, has just finished therapy, is about to enter therapy, or is a therapist,” claims a current witticism. Woody Allen, the popular culture’s image of the quintessential neurotic Jew, has revealed that he has been in analysis for over twenty years.

Not surprisingly, then, Jewish jokes about psychoanalysis have gone well beyond “Oedipus, Shmedipus”:

Goldstein has been in analysis for ten years, seeing his doctor four times a week. Finally, the analyst tells him that they’ve achieved all their goals, he doesn’t have to come back anymore. The man is terrified.

“Doctor,” he says, “I’ve grown very dependent on these meetings. I can’t just stop.”

The doctor gives Goldstein his home phone number. “If you ever need to,” he says, “call me at any time.”

Two weeks later, Sunday morning, six A.M., the phone rings in the doctor’s house. It’s Goldstein.

“Doctor,” he says, “I just had a terrible nightmare. I dreamed you were my mother, and I woke up in a terrible sweat.”

“So what did you do?”

“I analyzed the dream the way you taught me in analysis.”

“Yes?”

“Well, I couldn’t fall back to sleep. So I went downstairs to have some breakfast.”

“What’d you have?”

“Just a cup of coffee.”

“You call that a breakfast?”

Jewish parents are also famous (in some circles, infamous) for anxiously hovering over their children. “A Jewish man with parents alive,” Philip Roth wrote in Portnoy’s Complaint, “is a fifteen-year-old boy, and will remain a fifteen-year-old boy until they die.” A rabbi I know, who grew up in the intensely Orthodox neighborhood of Borough Park, Brooklyn, told me that it was his wife who taught him that one could express love for one’s children by taking pleasure in their personalities. “My parents,” he explained, “expressed their love through excessive nervousness and worrying.” That was also the case with Mell Lazarus, creator of the cartoon strip “Momma.” Reminiscing about his overly attentive mother at a seminar on Jewish humor, Lazarus recalled, “We had very many interesting conversations, about my posture for example.”

The overinvolvement of mothers in their children’s lives might well have several roots. The dominant middle-class ideology of the 1940s and 1950s—and Jews were quintessentially middle class—dictated that a father should work, and that the mother stay home with the children. A large number of highly educated Jewish women found themselves displacing all their intellectual energy, aspirations, and professional ambitions onto their children, particularl...