- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

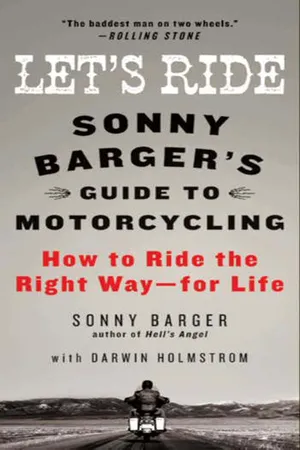

“The baddest man on two wheels.”

—Rolling Stone

One of the founders and the most famous member of the infamous Hell’s Angels Motorcycle Club, Ralph “Sonny” Barger says, “Let’s Ride” with this ultimate guide to motorcycling. With expert co-author Darwin Holmstrom—former writer for Motorcyclist magazine and author of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Motorcycles—Barger, “The archangel of all Hells Angels” (New York Post) is ready to take you on the ride of your life with this exhilarating and practical nuts-and-bolts master class in the fine art of freedom. So climb on, start it up, and…Let’s Ride!

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

eBook ISBN

9780061991370Subtopic

Social Science BiographiesChapter One

Dissecting the Beast

The Anatomy of a Motorcycle

Motorcycles seem like they should be simple because there’s really not much to them. You’ve got an engine, two wheels, tires, something to sit on, some controls to manage the machine, a tank for gasoline, and a frame to hold the whole works together.

In the early days of riding, the preceding description pretty much accounted for an entire motorcycle. The controls consisted of a cable going to a rudimentary carburetor, which was about as complex as a Turkish water pipe, and hopefully, a crude brake. The transmission was made up of a pulley that tightened a flat, smooth leather belt that ran from an output sprocket on the crankshaft of the engine to another pulley on the rear wheel. If the contraption had lights, they were likely powered by kerosene and turned on with matches or maybe a very rudimentary battery on more advanced models. A modern motorcycle has more computer chips than an early motorcycle had total moving parts.

Motorcycles weren’t that much more complicated when I started riding. There had been a few improvements, but not many. Instead of total-loss electrical systems with enormous lead-acid batteries, the first motorcycles I rode had extremely basic six-volt electrical systems. These didn’t provide enough juice to reliably power an electric starter, so we still had to kick-start our motorcycles. By then motorcycles had recirculating oiling systems so the rider no longer had to pump oil into the engine by hand, and chains took care of final drive duties instead of the smooth leather belts that spun the wheels on the earliest motorcycles, but overall, the bikes I started riding were closer to the motorized bicycles from the end of the nineteenth century than they were to the reliable, practical motorcycles we have today.

PUTTING THE MOTOR IN THE CYCLE

IN THIS BOOK I’M not going to teach you how to overhaul your motorcycle. Most modern motorcycles are too complicated for you to do much more than change the oil yourself, but you will need to become familiar with the essential parts of a motorcycle and how everything works together. If you already know these things, you might want to skip ahead to the next section, though it can never hurt to brush up.

The engine, of course, is what puts the motor in motorcycle. Engines come in two basic types: four-stroke and two-stroke. Two-stroke engines haven’t been used much in the United States over the past several decades because of emissions standards. They’re called “two-strokes” because every two strokes of the piston comprise one complete cycle. The piston goes down and draws in the fuel charge; it goes back up and fires the fuel charge. Two-strokes are simple engines that don’t have internal oil-lubrication systems. Some of the oil lubricates the inside of the engine, and the rest is burned with the exhaust, which is why they pollute so much. The last full-sized street-legal two-stroke motorcycle sold in the U.S. market was Yamaha’s RZ350 from the mid-1980s.

For several decades two-stroke engines dominated Grand Prix motorcycle racing because the engines are light and generate twice as many power pulses as a four-stroke engine, but they’ve been phased out over the past decade. In 2002 the top class switched from 500-cc two-strokes to 990-cc four-strokes, and in 2009 the 250-cc two-stroke class was retired, to be replaced by a 600-cc four-stroke class for the 2010 season. That leaves just the 125-cc class as the last of the two-stroke road racers.

But because two-stroke street bikes are too old and too small to be used as practical transportation, we won’t be discussing two-strokes in this book. The day may come when we’ll ride around on electric motorcycles powered by hydrogen fuel cells, but for the foreseeable future we’ll be riding motorcycles powered by four-stroke gasoline engines.

The basic systems of a four-stroke engine are the bottom end, the cylinder block, the piston, the cylinder, the combustion chamber, the cylinder head, and the fuel intake system.

The Crankcase

The crankcase is often referred to as the “bottom end” because it’s located at the bottom of almost every engine (though it’s at the center of opposed engines like those found on a BMW twin or a four- or six-cylinder Gold Wing—I’ll explain that later in this chapter). It consists of a crankshaft that rotates in a series of bearings. This rotation carries through the clutch, transmission, and final drive system, until it becomes the rotation of your rear tire on the pavement, which is what makes your motorcycle move down the road. Piston rods connect the crankshaft to the pistons.

These days most motorcycles are so reliable that if you regularly change your engine oil, you can ride for hundreds of thousands of miles and not give any thought to the bottom end, but that wasn’t always the case. Before we had the advanced oils, oiling systems, and bearing materials we have today, spinning a bearing or throwing a rod was a common occurrence. These are catastrophic failures that can result in internal parts of the engine exploding through cases and cylinder barrels and becoming external parts. This can be a little like a grenade going off between your legs, so it’s a very good thing that modern bikes have such reliable bottom ends.

To be fair, some of the methods we used to rely on for hot-rodding our engines, like “stroking” them (this refers to the practice of installing a different crankshaft that increases the length a piston travels up and down in the cylinder, effectively increasing cubic inches without making the cylinder itself any larger), improved performance, but they also put more stress on the parts and increased the likelihood that the engine would grenade between a rider’s legs. Modern motorcycle engines are too complex to easily stroke, though a few people still do this to their older 74-inch Shovelheads and Panheads. If you plan to do this to your engine, make sure you or whomever you hire to do the job knows what he’s doing.

The Cylinder Block(s)

Every gas-piston engine has one or more cylinder blocks. They are aluminum blocks (any practical modern motorcycle that you will consider buying will have an aluminum engine) with a hole or holes drilled in it or them for the piston or pistons. This hole is usually lined with a steel liner for durability, though some motorcycles have cylinder walls coated with harder alloys in place of steel liners.

On a single-cylinder or an inline engine like that found on a four-cylinder sport bike or a parallel-twin engine like that found on a Triumph, there will be just one cylinder block. There are a small number of V-four engines in production; these usually have one large cylinder block with four holes drilled in it.

On a V-twin like a Victory or a Harley, there are two cylinder blocks. V-twin owners usually call these cylinder blocks “barrels” or “jugs” because they look like water barrels or jugs. They may have earned the name “jugs” because some people think they look a little like certain parts of a well-endowed woman, but it takes a lot of imagination to see the resemblance.

All motorcycle cylinder blocks (except a few specialized cylinder blocks used to build drag-racing engines) will feature some sort of cooling system. On water-cooled bikes this will consist of water jackets around the cylinders (hollowed-out spaces through which cooling water circulates from the radiator to the cylinder block and back to the radiator again). On air-cooled bikes like Harleys and Victories this will just be a series of cooling fins that provide a surface area over which the passing air can remove the heat generated from the combustion process.

The type of cooling system is probably the single most important factor in reliability and longevity in a modern engine. Liquid cooling is generally the best type when it comes to making an engine last. All modern cars and trucks are liquid cooled, and most modern engines will run for more than two hundred thousand miles.

Today’s motorcycles are also water cooled, though air cooling is not necessarily a bad thing. As engine size increases, the amount of heat generated also increases, so it becomes harder to cool an engine with air alone when the cubic inches start to rise. As their air-cooled engines have grown larger, Harleys have had some cooling issues in recent years. To alleviate the problem Harley offers a system in which the rear cylinder shuts down at idle to help keep it cool when the bike is at rest.

Victory takes a different route. There are oil jets in a Victory engine that spray streams of cooling oil at the bottoms of the pistons, right at the area in which the most heat is generated. The cylinders still crank out a hellacious amount of heat and will bake your inner thigh on a hot Arizona day, but that is true of just about every motorcycle. If you want to ride in air-conditioned comfort, you’re reading the wrong book. I can tell you from tens of thousands of miles of experience that Victory engines seem to run cooler in stop-and-go traffic than Harley engines, which is one of the things I like about Victory motorcycles.

Harley does make what seems like a very good liquid-cooled motorcycle: the V-Rod. I have friends who own them and they speak very highly of them.

The Pistons, Cylinder, Combustion Chamber, Cylinder Head, and Fuel Intake System

The pistons—the aluminum slugs that go up and down in the cylinder blocks—are the beating heart of a motorcycle engine. They’re powered by a fuel-air charge that burns in the combustion chamber, which is the area at the top of the cylinder. This burning generates an engine’s energy as well as most of its heat.

The cylinder head is the assembly that sits atop the cylinder block. It contains valves that open and close to allow the fuel charge to get in and the spent exhaust gases to get out. Motorcycle engines can have anywhere from two to five valves per cylinder. Most Harleys have two valves per cylinder: one intake and one exhaust. Victory motorcycles all have four valves: two intake valves and two exhaust valves. Some Hondas have three valves per cylinder, and a handful of Yamahas had five valves per cylinder, but most modern motorcycles will have four valves per cylinder.

With very few exceptions, the fuel-air charge is injected by electronically controlled atomizers on modern motorcycles, though there are still a few good used bikes out there that have old-fashioned carburetors mixing the fuel-air charge and getting it into the combustion chamber. Triumph recently switched from carburetion to fuel injection on its Bonneville-series twins, and these bikes had been some of the last new models to feature carburetors.

THE FOUR STROKES OF A FOUR-STROKE

FOUR-STROKE ENGINES ARE CALLED four-strokes because each cycle of the combustion process consists of four strokes of the piston. The first (downward) stroke is called the “intake stroke” because the intake valves open on this stroke and the downward-moving piston draws in the fuel-and-air charge. The second (upward) stroke is called the “compression stroke” because the upward-moving piston compresses the fuel-air charge, which is ignited very near the top of the compression stroke (called “top dead center,” or TDC). The energy generated by this ignition is called “combustion,” and it’s what gives its name to the third (downward) stroke, the combustion stroke (also called the “power stroke”). The fourth (upward) stroke is called the “exhaust stroke” because the exhaust valves open on this stroke, allowing the upward-moving piston to force the spent exhaust gases out through the open valves.

REDLINING

I’M NOT A HUGE fan of Harley-Davidson motorcycles. That is partly because for many years Harley sold motorcycles that were worn-out antiques even when they were new. In 1969 AMF (American Machinery and Foundry) bought Harley. By that time the Japanese had begun to introduce motorcycles with modern technology, and in the following years the pace of development of motorcycle technology quickened. When AMF sold Harley in 1981, the motorcycles coming from Japan were so highly developed that they made the motorcycles they produced in the 1960s look like antiques.

The bikes Harley built between 1969 and 1981 had barely changed; if anything, they got even worse. AMF looked at Harley as a cash cow and milked it dry. The company put very little money into product development. Instead, AMF ramped up production so that besides selling antiquated motorcycles, Harley’s quality control went down the toilet; not only were Harley’s motorcycles handicapped with old-fashioned technology like cast-iron engines, but they also became increasingly unreliable.

It wasn’t that way when I started riding. In the 1950s all but the most expensive high-performance motorcycles had cast-iron engines and Harleys were as good as or better than any other bike on the market. But within fifteen years the Japanese, German, and Italian manufacturers were selling motorcycles with aluminum cylinder blocks almost exclusively. Besides Harley, only the British still used cast iron for their cylinder blocks, and it didn’t work out too well for them: by the early 1980s the entire British motorcycle industry had gone bankrupt. In fact, the British motorcycle industry would have gone out of business many years earlier if the UK government hadn’t propped it up for the last twenty years of its existence.

Harley almost died at the same time. The Motor Company continued to build bikes with cast-iron cylinder jugs until the mid-1980s, when the aluminum Evolution engine hit the market. Because it is important to me as a patriot to ride an American motorcycle, I was stuck riding unreliable cast-iron Shovelheads all those years, and they were terrible motorcycles. Back then I spent as much time wrenching as riding, and it pissed me off. Harleys got a lot better after they started building the Evolution engines, but even today they are still old-fashioned air-cooled pushrod engines. (That means they have their cams down in the bottom end, and they use pushrods to operate the valves.)

Only a few other motorcycle manufacturers still use pushrods, like Royal Enfield from India, Moto Guzzi from Italy, and Ural from Russia, none of which are terribly reliable motorcycles. I wouldn’t consider any of these brands when buying a motorcycle for practical transportation. Almost every motorcycle built today uses modern overhead-cam systems. Even most V-twin engines, like the engine found in my Victory, feature overhead cams.

Overhead-cam engines are more efficient and generate more power than pushrod engines, all else being equal, because they keep the valves under more direct control, allowing the engine to rev higher before valve float sets in. Valve float occurs when the cam pushes open the valve more rapidly than the valve spring can close it—it’s a bad thing. If your bike is equipped with a tachometer, it will have a red zone marked on its face beginning at a certain rpm (revolutions per minute) range. The rpm range where the red zone begins is called the “redline,” and is usually the engine speed at which valve float sets in. If you run your tach needle past the redline, you can destroy your engine.

Having an engine explode between your legs is not an experience I’d wish on my worst enemy. It’s rare that a motorcycle engine will explode like a grenade, sending shrapnel outside the engine cases, but what happens when you spin a bearing or throw a rod can be just as deadly.

Usually you’ll be going faster than you should be when this happens, which may well be why your engine explodes. You’ll be riding along, enjoying the open road, and your engine will seize up. This in turn stops your rear tire from turning and it happens in less time than it takes for your heart to beat. If you’re not covering your clutch (we’ll discuss this in the advanced riding section of the book) and don’t immediately pull in the clutch lever to disengage the rear wheel from the seized engine, you’ll skid out of control and crash.

If your bike starts to skid sideways before you pull in the clutch, you’ll have an even worse crash. When your tire is skidding, you lose all traction. When you pull in the clutch and the tire starts turning again, you’ll regain traction. If your bike has started to skid to one side or the other, when you regain traction it will snap back in the opposite direction. This can easily happen with such force that it launches the entire motorcycle in the air. Of course you’ll get launched with it. This is called “high-siding,” and short of hitting a tree or a guardrail, it’s about the worse kind of single-vehicle crash you can have on a motorcycle.

Overhead-cam engines have much higher redlines than do pushrod engines, which is why they produce more power, but that isn’t the main reason I advise against buying most of the bikes that use pushrods. During normal street driving you seldom get anywhere near the engine’s redline; the problem is that most of the engines that use pushrods use other outdated technology, too, which is why pushrod engines tend to be less reliable than those with overhead cams.

ENGINE TYPES

THERE ARE AS MANY different types of four-stroke motorcycle engines as there are types of motorcycles. Several basic engine configurations exist, and unless you plan to drop a fortune buying some rare, exotic machine, the bike you end up with will feature an engine in one of the following configurations:

- Single Cylinder

- V-Twin

- Parallel Twin

- L-Twin

- Opposed Twin

- Inline Triple

- Inline Four

- V-Four

- Opposed Four

- Opposed Six

There are a few oddball designs other than these, but without exception they will either be antiques, or they will be rare (and expensive) exotics, both of which are better suited to collections sitting in museums than they are for useful transportation because the spare parts needed to keep them on the road will be virtually unobtainable.

For example, over the years there have been a handful of motorcycles built with V-8 engines, like the racing bikes Moto Guzzi made in the mid-1950s. Over the years a few other manufacturers have built V-8-powered motorcycles, but not many. Italian Giancarlo Morbidelli developed a V-8 sport bike in the mid-1990s, but at a price tag of $60,000, he only sold four of them. A company called Boss Hoss makes gigantic motorcycles powered by automotive-type V-8 engines, but these bikes are so huge that they are just novelties even for experienced riders. They’re expensive novelties, too, starting at around $40,000 for a base model and climbing well past the $50,000 mar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Introduction: Why Ride?

- Chapter One - Dissecting the Beast: The Anatomy of a Motorcycle

- Chapter Two - Types of Bikes: What to Ride

- Chapter Three - The Fundamentals of Riding

- Chapter Four - Evaluating a Used Motorcycle

- Chapter Five - Buying a Bike

- Chapter Six - Advanced Riding Techniques

- Chapter Seven - Living with a Motorcycle

- Appendix: Motorcycle Resources

- About the Authors

- Also by Sonny Barger

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Let's Ride by Sonny Barger,Darwin Holmstrom in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.