- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

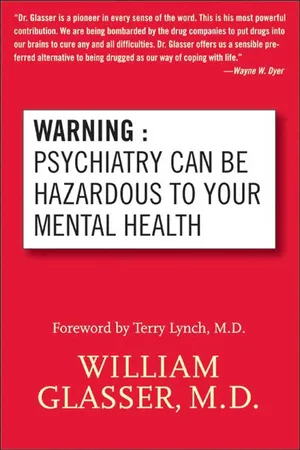

Warning: Psychiatry Can Be Hazardous to Your Mental Health

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Warning: Psychiatry Can Be Hazardous to Your Mental Health by William Glasser, M.D. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Education Counseling. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

thirteen

Important Material from Al Siebert, Ph.D., and Anthony Black

Very few mental health professionals have gone through what Al Siebert experienced as a young man. Like myself, Al is a follower of Peter Breggin and is a member of the ICSPP. What follows, written by Al Siebert, is an all too common example of how psychiatry can be hazardous to your mental health. It is reproduced exactly as it was written for this book.

In March 1965, I had finished all my course work in the clinical psychology program at the University of Michigan and was starting my doctoral dissertation research. To support myself and my wife I was teaching part-time for the Psychology Department and working half-time as a staff psychologist at the Neuropsychiatric Institute (NPI) at the University of Michigan hospital.

At the urging of Alexander Giora, my supervisor at NPI, I applied for a two-year, postdoctoral National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) fellowship at the Menninger Foundation in Topeka, Kansas. Martin Mayman, director of psychology training at Menninger, arranged for me to fly to Topeka for two days of interviews. My department chairman, Wilbert J. McKeachie, and others all rushed their letters of recommendation to Mayman. Several weeks later Mayman telephoned me and said I’d been selected to be one of the three NIMH Fellows to start their program in September.

The Menninger postdoctoral fellowship was a significant honor. My instructors and fellow graduate students were especially delighted because I was the first graduate in clinical psychology from Michigan to go to Menninger.

I completed my dissertation research quickly and passed my oral defense of it in June. With no more classes to teach, I arranged to work full-time at NPI for the summer. Now officially a “doctor, “ I was issued a long white coat with my name on the pocket. I enjoyed the new status. I liked feeling the difference in how people working at the hospital looked at me and listened to me. I was the same person as before, but their perception of me was different.

Looking ahead to the start of the Menninger program in September, I reread the description of the program philosophy. I found one passage especially attractive:

“The specific goals of the program are to foster a searching curiosity about clinical processes that will generate new research into the nature of these processes. The program allows Fellows a two-year ’moratorium’ in which they are free to re-examine and reintegrate their theoretical, clinical, and professional skills.”

I decided to get a head start. I started writing a list of questions:

Why am I now called a mental health professional when all my courses have been about mental illness? I’ve never had a class or even a lecture on mental health!

Why do psychiatrists put so many people into mental hospitals when there is so much evidence that hospitalization is not effective?

Why do psychiatrists always blame their patients when their recommended treatments don’t work?

Why are there so many kinds of schizophrenia?

If there is no cure for schizophrenia, what don’t psychiatrists and psychologists understand about schizophrenia?

I also wondered: Why do most people who want to make the world a better place focus on trying to get other people to change? Why don’t they work on themselves?

With more personal time now available to me, I read Atlas Shrugged, by Ayn Rand. I was intrigued with her way of showing how people act in selfish ways while denying their selfish motives. Then an interesting coincidence occurred at NPI. A psychiatric resident complained to me about a patient. He said, “That patient refuses to believe I’m acting for her own good.”

“Are you?” I asked.

“Of course.”

“By working with her, “ I asked, “aren’t you learning how to be a psychiatrist?”

“Yes.”

“Won’t you enjoy the prestige, money, and working conditions that psychiatrists have?”

“Yes.”

“If you succeed with her, won’t the nurses and supervisors think well of you?”

“Yes.”

“If you help her, won’t you gain her appreciation?”

“Probably.”

“If you can get her out of the hospital, won’t that help reduce your taxes?”

Nodding, he said, “Indirectly.”

“And you want her to believe that you’re working entirely for her own good?”

He clenched his jaw. “But I am!” he declared, then walked back into his office and yanked his door shut.

I became preoccupied wondering what internal mechanism blinds a person from recognizing their selfish motivation while insisting their efforts are unselfish. Sigmund Freud discovered some subconscious mechanisms that keep people from being fully conscious—mechanisms such as denial, repression, and projection. I wondered if there might be a hidden defense mechanism inside the character structure of people who force unwanted help on others. I decided to name the defense mechanism “charity” as an operational definition. “What is the motivation, “ I wondered, “that compels someone to force help on others despite protests that they don’t want help?”

And I began to wonder, “What happens in the training of psychiatrists that creates this self-deception?”

A few days later, Frank, one of the psychiatric residents asked me to be present in his office when he met with one of his patients. I’d done the psychological testing of Tony, a twenty-one-year-old, unemployed auto factory worker. He’d gotten into a fistfight with his father, beaten him up, and driven off in his father’s car. The father called the police, who located the car and arrested Tony for auto theft. The judge had sent Tony to the hospital for a psychiatric evaluation.

Tony’s caseworker, Lois, was also present. Frank said sternly, “Tony, your behavior is sick. We can treat your problem, but you must accept that you’re mentally ill before we can help you.”

Tony shook his head. “I’m not a crazy person.”

“You are mentally ill!” Frank said, “You must accept that.”

“No, I’m not! You doctors are crazy if you think I’m nuts!”

“We’ve argued about this before. You must believe you’re mentally ill or we can’t help you.”

Tony’s face got red. His nostrils flared and he breathed faster. “I’m not mentally ill!”

“Yes, you are!” Frank said.

“No, I’m not!”

“Yes, you are!”

“No!”

Lois and I looked at each other. Frank gave up. Everyone sat in silence. Then Frank said, “The meeting is over.” He nodded to the aide to take Tony back to the closed ward.

Frank sat dejectedly with his head down. Lois and I left without saying anything to him.

“I’m shocked by what I just witnessed, “ I said to Lois.

“Why?” she said. “The first thing a psychiatrist must do is convince the patient that he’s mentally ill.”

“That’s what I’m shocked to learn. During graduate school, I read hundreds of articles and books on psychotherapy. None of them mention what we just saw! The research reports about psychotherapy are silent about a major variable! This means that most reports about psychiatric treatment are badly flawed!”

“Al, do you agree that Tony is mentally ill?”

“No.” I said. “He’s a kid with poor control over his impulses, but I’ve seen many like him. At the juvenile court where I worked, he would be typical. He’s okay. His father used to beat him when he was a boy.”

“He told me that.”

“This is a case of another dumb parent not realizing that one day his son will be bigger and stronger and may decide to get even. No, Tony doesn’t have a mental disorder.”

Several days later we heard that Tony had escaped from the hospital. I stopped Frank in the hallway and asked him, “What happened the other day in your office? You seemed uptight. What’s going on?”

Frank took a deep breath and shook his head. “Al, I’m trying to do what my supervisor tells me, but I don’t like it. When I ask questions about why I should talk patients into believing they’re mentally ill, he tells me to work it out with my therapist.”

“I heard that you’ve been warned to be more cooperative.”

“This is confidential.”

“Sure.”

“I met with my supervisor before that session with Tony. He told me that my ‘case’ was discussed at a senior staff meeting. He said if I didn’t work out my problems and my resistance to the program, they would drop me.”

“That’s a heavy-duty threat.”

“I tried to do what my supervisor told me to do with Tony, but I hated it. I’m worried. If I get dropped from here, it would be difficult to find another residency. I may have to give up psychiatry altogether. That’s a lot of years wasted. I’ve taken out loans…” He paused for a while, then said, “Thank you for your concern, “ and walked away.

It shocked me to see that psychiatric residents who question what they are told to say and think risk being screened out of the profession. I saw that the training program for psychiatrists used a reduction of cognitive dissonance technique. When people cooperate in stating and defending a false belief, a certain percentage of them will gradually accept the belief as true.

I looked for opportunities to learn more.

A twenty-five-year-old man was admitted to NPI with the diagnosis “acute paranoid state.” I arranged to be the psychologist who tested him.

In my office I asked him, “Why are you here in the hospital?”

He clenched his jaw. “My wife and family say I don’t think right. They say I’m talking crazy. They pressured me into this place.”

“You’re a voluntary admission, aren’t you?”

“Yes. It won’t do any good, though. They’re the ones who need a psychiatrist.”

“Why do you say that?”

“I work in sales in a big company. Everyone is out for themselves. I don’t like it. I don’t like to pressure people or trick them into buying to put bucks in my pocket. The others seem to go for it. Selfish, clawing to get ahead. My boss says I have the wrong attitude. He rides me all the time.”

“What’s the problem with your family?”

“I talked about quitting and going to veterinarian school. I like animals. I’d like that work. My wife says I’m not thinking right. She wants me to stay in business and work up into management. She went to my parents and got them on her side.”

“I still don’t see the reason for your being here.”

“They’re upset because I started yelling at them about how selfish they are. My wife wants a husband who earns big money, owns a fancy home, and drives an expensive car. She doesn’t want to be the wife of a veterinarian. They can’t see how selfish they are by trying to make me fit into a slot so they can be happy. Everyone is telling me what I should think and what should make me happy.”

“So you told them how selfish they are?”

“Yes. They couldn’t take it. They insist they’re only interested in my welfare.” He leaned over and held his face in his hands.

This seemed to confirm the blind selfishness behind the compulsion to force “charity” on others, but where did the “paranoid” diagnosis come from?

I asked him, “Did you tell the admitting physician about them trying to make you think right?”

“Yes. Everyone’s trying to brainwash me. My wife, parents, the sales manager. Everyone’s trying to push their thinking into my head.”

There it was! The psychiatric resident heard him saying, “People are trying to force thoughts into my mind.” The resident had been trained to diagnose this as a symptom of paranoia instead of seeing the truth in the statement.

I asked, “What has your doctor said to you?”

“He doesn’t listen. He says I must believe I’m mentally ill. It’s crazy.”

I was beginning to see that. Psychiatrists put a patient into a distressing bind when they say to a patient, “You must accept into your mind the thought that you are mentally ill because you believe people are trying to force thoughts into your mind.”

I went for long walks by myself to think about what I was discovering. I was learning much about the training of psychiatrists and the actual practice of psychiatry that had not been covered in my courses. No psychotherapy research reports address whether or not patients were told they must believe that they are mentally ill. No research reports identify what percentage of patients forced to submit to therapy have been told it is for their own good. I was learning that a psychiatrist in training who is strongly motivated to acquire the status, income, and power of a doctor of psychiatry must set aside his or her critical thinking skills.

My wife was concerned about my preoccupations. I reassured her that I just needed time to sort out some professional dilemmas.

I wondered, “Where does self-deceptive unselfishness, this compulsion to force help on others, come from?” I speculated that people compelled to force unwanted help onto others are indirectly trying to build up feelings of esteem. They gain esteem from others by doing what “good” people do; they help people seen as sick, impoverished, or abnormal in some diminished way. Is it possible that the need to be surrounded by poorly esteemed people is why psychiatrists see mental illness all around them?

I wondered, “If someone declares that they are Jesus or the Virgin Mary, why do psychiatrists and others try so hard to remove that thought from the person’s mind? Why do they lock the person up for years and force medications on them while claiming they are doing it for the person’s own good? Why are psychiatrists compelled to stop other humans from enjoying extreme feelings of self-esteem? Is the perception of mental illness in another person a stress reaction in the observer?” I wondered how I could test my hypothesis.

An Experimental Interview

A fortunate coincidence occurred a few ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword - by Terry Lynch, M.D.

- Preface

- One: Who Am I, Who Are You, and What Is Mental Health?

- Two: The Difference between Physical Health and Mental Health

- Three: Unhappiness Is the Cause of Your Symptoms

- Four: The First Choice Theory Focus Group Session: Choosing Your Symptoms

- Five: We Have Learned to Destroy Our Own Happiness

- Six: Introducing External Control Psychology and Choice Theory

- Seven: The Third Choice Theory Focus Group Session—Joan, Barry, and Roger

- Eight: The Role of Our Genes in Our Mental Health

- Nine: How Can You Say That We Choose Our Symptoms?

- Ten: The Fourth Choice Theory Focus Group Session

- Eleven: Luck, Intimacy, and Our Quality World

- Twelve: The Fifth Choice Theory Focus Group Session

- Thirteen: Important Material from Al Siebert, Ph.D., and Anthony Black

- Fourteen: You Have Finished the Book, Now What?

- Index

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Praise

- Also by William Glasser, M.D.

- Appendix

- Copyright

- About the Publisher