CHAPTER 1

A Lingering Scent of Eden

YOU MAY NEVER have heard of the Bia∤owieża Puszcza. But if you were raised somewhere in the temperate swathe that crosses much of North America, Japan, Korea, Russia, several former Soviet republics, parts of China, Turkey, and Eastern and Western Europe—including the British Isles—something within you remembers it. If instead you were born to tundra or desert, subtropics or tropics, pampas or savannas, there are still places on Earth kindred to this puszcza to stir your memory, too.

Puszcza, an old Polish word, means “forest primeval.” Straddling the border between Poland and Belarus, the half-million acres of the Bia∤owieża Puszcza contain Europe’s last remaining fragment of old-growth, lowland wilderness. Think of the misty, brooding forest that loomed behind your eyelids when, as a child, someone read you the Grimm Brothers’ fairy tales. Here, ash and linden trees tower nearly 150 feet, their huge canopies shading a moist, tangled understory of hornbeams, ferns, swamp alders and crockery-sized fungi. Oaks, shrouded with half a millennium of moss, grow so immense here that great spotted woodpeckers store spruce cones in their three-inch-deep bark furrows. The air, thick and cool, is draped with silence that parts briefly for a nutcracker’s croak, a pygmy owl’s low whistle, or a wolf’s wail, then returns to stillness.

The fragrance that wafts from eons of accumulated mulch in the forest’s core hearkens to fertility’s very origins. In the Bia∤owieża, the profusion of life owes much to all that is dead. Almost a quarter of the organic mass aboveground is in assorted stages of decay—more than 50 cubic yards of decomposing trunks and fallen branches on every acre, nourishing thousands of species of mushrooms, lichens, bark beetles, grubs, and microbes that are missing from the orderly, managed woodlands that pass as forests elsewhere.

Together those species stock a sylvan larder that provides for weasels, pine martens, raccoons, badgers, otters, fox, lynx, wolves, roe deer, elk, and eagles. More kinds of life are found here than anywhere else on the continent—yet there are no surrounding mountains or sheltering valleys to form unique niches for endemic species. The Bia∤owieża Puszcza is simply a relic of what once stretched east to Siberia and west to Ireland.

The existence in Europe of such a legacy of unbroken biological antiquity owes, unsurprisingly, to high privilege. During the 14th century, a Lithuanian duke named W∤adys∤aw Jagie∤∤o, having successfully allied his grand duchy with the Kingdom of Poland, declared the forest a royal hunting preserve. For centuries, it stayed that way. When the Polish-Lithuanian union was finally subsumed by Russia, the Bia∤owieża became the private domain of the tsars. Although occupying Germans took lumber and slaughtered game during World War I, a pristine core was left intact, which in 1921 became a Polish national park. The timber pillaging resumed briefly under the Soviets, but when the Nazis invaded, a nature fanatic named Hermann Göring decreed the entire preserve off-limits, except by his pleasure.

Following World War II, a reportedly drunken Josef Stalin agreed one evening in Warsaw to let Poland retain two-fifths of the forest. Little else changed under communist rule, except for construction of some elite hunting dachas—in one of which, Viskuli, an agreement was signed in 1991 dissolving the Soviet Union into free states. Yet, as it turns out, this ancient sanctuary is more threatened under Polish democracy and Belarusian independence than it was during seven centuries of monarchs and dictators. Forestry ministries in both countries tout increased management to preserve the Puszcza’s health. Management, however, often turns out to be a euphemism for culling—and selling—mature hardwoods that otherwise would one day return a windfall of nutrients to the forest.

IT IS STARTLING to think that all Europe once looked like this Puszcza. To enter it is to realize that most of us were bred to a pale copy of what nature intended. Seeing alders with trunks seven feet wide, or walking through stands of the tallest trees here—gigantic Norway spruce, shaggy as Methuselah—should seem as exotic as the Amazon or Antarctica to someone raised among the comparatively puny, second-growth woodlands found throughout the Northern Hemisphere. Instead, what’s astonishing is how primally familiar it feels. And, on some cellular level, how complete.

Andrzej Bobiec recognized it instantly. As a forestry student in Krakow, he’d been trained to manage forests for maximum productivity, which included removing “excess” organic litter lest it harbor pests like bark beetles. Then, on a visit here he was

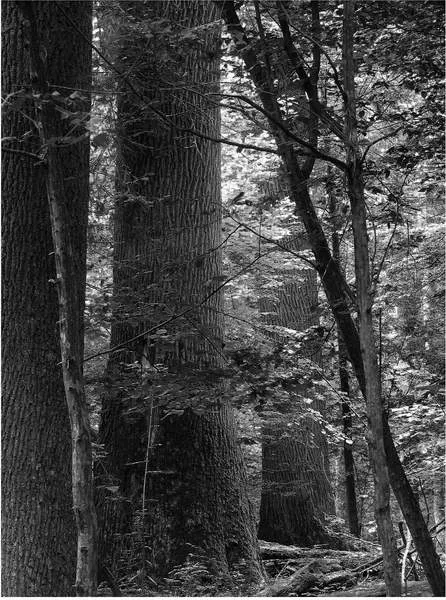

Five-hundred-year-old oaks. Bia∤owieża Puszcza, Poland. PHOTO BY JANUSZ KORBEL.

stunned to discover 10 times more biodiversity than in any forest he’d ever seen.

It was the only place left with all nine European woodpecker species, because, he realized, some of them only nest in hollow, dying trees. “They can’t survive in managed forests,” he argued to his forestry professors. “The Bia∤owieża Puszcza has managed itself perfectly well for millennia.”

The husky, bearded young Polish forester became instead a forest ecologist. He was hired by the Polish national park service. Eventually, he was fired for protesting management plans that chipped ever closer to the pristine core of the Puszcza. In various international journals, he blistered official policies that asserted that “forests will die without our thoughtful help,” or that justified cutting timber in the Bia∤owieża’s surrounding buffer to “reestablish the primeval character of stands.” Such convoluted thinking, he accused, was rampant among Europeans who have hardly any memory of forested wilderness.

To keep his own memory connected, for years he daily laced his leather boots and hiked through his beloved Puszcza. Yet although he ferociously defends those parts of this forest still undisturbed by man, Andrzej Bobiec can’t help being seduced by his own human nature.

Alone in the woods, Bobiec enters into communion with fellow Homo sapiens through the ages. A wilderness this pure is a blank slate to record human passage: a record he has learned to read. Charcoal layers in the soil show him where gamesmen once used fire to clear parts of the forest for browse. Stands of birch and trembling aspen attest to a time when Jagie∤∤o’s descendants were distracted from hunting, perhaps by war, long enough for these sun-seeking species to recolonize game clearings. In their shade grow telltale seedlings of the hardwoods that were here before them. Gradually, these will crowd out the birch and aspen, until it will be as if they were never gone.

Whenever Bobiec happens on an anomalous shrub like hawthorn or on an old apple tree, he knows he’s in the presence of the ghost of a log house long ago devoured by the same microbes that can turn the giant trees here back into soil. Any lone, massive oak he finds growing from a low, clover-covered mound marks a crematorium. Its roots have drawn nourishment from the ashes of Slavic ancestors of today’s Belorusians, who came from the east 900 years ago. On the northwest edge of the forest, Jews from five surrounding shtetls buried their dead. Their sandstone and granite headstones from the 1850s, mossy and tumbled by roots, have already worn so smooth that they’ve begun to resemble the pebbles left by their mourning relatives, who themselves long ago departed.

Andrzej Bobiec passes through a blue-green glade of Scots pine, barely a mile from the Belarusian border. The waning October afternoon is so hushed, he can hear snowflakes alight. Suddenly, there’s a crashing in the underbrush, and a dozen wisent—Bison bonasus, European bison—burst from where they’ve been browsing on young shoots. Steaming and pawing, their huge black eyes glance just long enough for them to do what their own ancestors discovered they must upon encountering one of these deceptively frail bipeds: they flee.

Just 600 wisent remain in the wild, nearly all of them here—or just half, depending on what’s meant by here. An iron curtain bisects this paradise, erected by the Soviets in 1980 along the border to thwart escapees to Poland’s renegade Solidarity movement. Although wolves dig under it, and roe deer and elk are believed to leap it, the herd of these largest of Europe’s mammals remains divided, and with it, its gene pool—divided and mortally diminished, some zoologists fear. Once, following World War I, bison from zoos were brought here to replenish a species nearly extirpated by hungry soldiers. Now, a remnant of a Cold War threatens them again.

Belarus, which well after communism’s collapse has yet to remove statues of Lenin, also shows no inclination to dismantle the fence, especially as Poland’s border is now the European Union’s. Although just 14 kilometers separate the two countries’ park headquarters, to see the Belovezhskaya Pushcha, as it is called in Belorusian, a foreign visitor must drive 100 miles south, take a train across the border to the city of Brest, submit to pointless interrogation, and hire a car to drive back north. Andrzej Bobiec’s Belorusian counterpart and fellow activist, Heorhi Kazulka, is a pale, sallow invertebrate biologist and former deputy director of Belarus’s side of the primeval forest. He was also fired by his own country’s park service, for challenging one of the latest park additions—a sawmill. He cannot risk being seen with Westerners. Inside the Brezhnev-era tenement where he lives at the forest’s edge, he apologetically offers visitors tea and discusses his dream of an international peace park where bison and moose would roam and breed freely.

The Pushcha’s colossal trees are the same as those in Poland; the same buttercups, lichens, and enormous oak leaves; the same circling white-tailed eagles, heedless of the razor-wire barrier below. In fact, on both sides, the forest is actually growing, as peasant populations leave shrinking villages for cities. In this moist climate, birch and aspen quickly invade their fallow potato fields; within just two decades, farmland gives way to woodland. Under the canopy of the pioneering trees, oak, maple, linden, elm, and spruce regenerate. Given 500 years without people, a true forest could return.

The thought of rural Europe reverting one day to original forest is heartening. But unless the last humans remember to first remove Belarus’s iron curtain, its bison may wither away with them.

CHAPTER 2

Unbuilding Our Home

“ ‘If you want to destroy a barn,’ a farmer once told me, ‘cut an eighteen-inch-square hole in the roof. Then stand back.’ ”

—architect Chris Riddle

Amherst, Massachusetts

ON THE DAY after humans disappear, nature takes over and immediately begins cleaning house—or houses, that is. Cleans them right off the face of the Earth. They all go.

If you’re a homeowner, you already knew it was only a matter of time for yours, but you’ve resisted admitting it, even as erosion callously attacked, starting with your savings. Back when they told you what your house would cost, nobody mentioned what you’d also be paying so that nature wouldn’t repossess it long before the bank.

Even if you live in a denatured, postmodern subdivision where heavy machines mashed the landscape into submission, replacing unruly native flora with obedient sod and uniform saplings, and paving wetlands in the righteous name of mosquito control—even then, you know that nature wasn’t fazed. No matter how hermetically you’ve sealed your temperature-tuned interior from the weather, invisible spores penetrate anyway, exploding in sudden outbursts of mold—awful when you see it, worse when you don’t, because it’s hidden behind a painted wall, munching paper sandwiches of gypsum board, rotting studs and floor joists. Or you’ve been colonized by termites, carpenter ants, roaches, hornets, even small mammals.

Most of all, though, you are beset by what in other contexts is the veritable stuff of life: water. It always wants in.

After we’re gone, nature’s revenge for our smug, mechanized superiority arrives waterborne. It starts with wood-frame construction, the most widely used residential building technique in the developed world. It begins on the roof, probably asphalt or slate shingle, warranted to last two or three decades—but that warranty doesn’t count around the chimney, where the first leak occurs. As the flashing separates under rain’s relentless insistence, water sneaks beneath the shingles. It flows across four-by-eight-foot sheets of sheathing made either of plywood or, if newer, of woodchip board composed of three- to four-inch flakes of timber, bonded together by a resin.

Newer isn’t necessarily better. Wernher Von Braun, the German scientist who developed the U.S. space program, used to tell a story about Colonel John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth. “Seconds before lift-off, with Glenn strapped into that rocket we built for him and man’s best efforts all focused on that moment, you know what he said to himself? ‘Oh, my God! I’m sitting on a pile of low bids!’ ”

In your new house, you’ve been sitting under one. On the one hand, that’s all right: by building things so cheaply and lightly, we use fewer of the world’s resources. On the other hand, the massive trees that yielded the great wooden posts and beams that still support medieval European, Japanese, and early American walls are now too precious and rare, and we’re left to make do with gluing together smaller boards and scraps.

The resin in your cost-conscious choice of a woodchip roof, a waterproof goo of formaldehyde and phenol polymer, was also applied along the board’s exposed edges, but it fails anyway because moisture enters around the nails. Soon they’re rusting, and their grip begins to loosen. That presently leads not only to interior leaks, but to structural mayhem. Besides underlying the roofing, the wooden sheathing secures trusses to each other. The trusses—premanufactured braces held together with metal connection plates—are there to keep the roof from splaying. But when the sheathing goes, structural integrity goes with it.

As gravity increases tension on the trusses, the 1/4-inch pins securing their now-rusting connector plates pull free from the wet wood, which now sports a fuzzy coating of greenish mold. Beneath the mold, threadlike filaments called hyphae are secreting enzymes that break cellulose and lignin down into fungi food. The same thing is happening to the floors inside. When the heat went off, pipes burst if you lived where it freezes, and rain is blowing in where windows have cracked from bird collisions and the stress of sagging walls. Even where the glass is still intact, rain and snow mysteriously, inexorably work their way under sills. As the wood continues to rot, trusses start to collapse against each other. Eventually the walls lean to one side, and finally the roof falls in. That barn roof with the 18-by-18-inch hole was likely gone inside of 10 years. Your house’s lasts maybe 50 years; 100, tops.

While all that disaster was unfolding, squirrels, raccoons, and lizards have been inside, chewing nest holes in the drywall, even as woodpeckers rammed their way through from the other direction. If they were initially thwarted by allegedly indestructible siding made of aluminum, vinyl, or the maintenance-free, portland-cement-cellulose-fiber clapboards known as Hardie planks, they merely have to wait a century before most of it is lying on the ground. Its factory-impregnated color is nearly gone, and as water works its inevitable way into saw cuts and holes where the planks took nails, bacteria are picking over its vegetable matter and leaving its minerals behind. Fallen vinyl siding, whose color began to fade early, is now brittle and cracking as its plasticizers degenerate. The aluminum is in better shape, but salts in water pooling on its surface slowly eat little pits that leave a grainy white coating.

For many decades, even after being exposed to the elements, zinc galvanizing has protected your steel heating and cooling ducts. But water and air have been conspiring to convert it to zinc oxide. Once the coating is consumed, the unprotected thin sheet steel disintegrates in a few years. Long before that, the water-soluble gypsum in the sheetrock has washed back into the earth. That leaves the chimney, where all the trouble began. After a century, it’s still standing, but its bricks have begun to drop and break as, little by little, its lime mortar, exposed to temperature swings, crumbles and powders.

If you owned a swimming pool, it’s now a planter box, filled with either the offspring of ornamental saplings that the developer imported, or with banished natural foliage that was still hovering on the subdivision’s fringes, awaiting the chance to retake its territory. If the house’s foundation involved a basement, it too is filling with soil and plant life. Brambles and wild grapevines are snaking around steel gas pipes, which will rust away before another century goes by. White plastic PVC plumbing has yellowed and thinned on the side exposed to the light, where its chloride is weathering to hydrochloric acid, dissolving itself and its polyvinyl partners. Only the bathroom tile, the chemical properties of its fired ceramic not unlike those of fossils, is relatively unchanged, although it now lies in a pile mixed with leaf litter.

After 500 years, what is left depends on where in the world you lived. If the climate was temperate, a forest stands in place of a suburb; minus a few hills, it’s begun to resemble what it was before developers, or the farmers they expropriated, first saw it. Amid the trees, half-concealed by a spreading understory, lie aluminum dishwasher parts and stainless steel cookware, their plastic handles splitting but still solid. Over the coming centuries, although there will be no metallurgists around to measure it, the pace at which aluminum pits and corrodes will finally be revealed: a relatively new material, aluminum was unknown to early humans because its ore must be electrochemically refined to form metal.

The chromium alloys that give stainless steel its resilience, however, will probably continue to do so for millennia, especially if the pots, pans, and carbon-tempered cutlery are buried out of the reach of atmospheric oxygen. One hundred thousand years hence, the intellectual development of whatever creature digs them up might be kicked abruptly to a higher evolutionary plane by the discovery of ready-made tools. Then again, lack of knowledge of how to duplicate them could be a demoralizing frustration—or an awe-arousing mystery that ignites religious consciousness.

If you were a desert dweller, the plastic components of modern life flake and peel away faster, as polymer chains crack under an ultraviolet barrage of daily sunshine. With less moisture, wood lasts longer there, though any metal in contact with salty desert ...