![]()

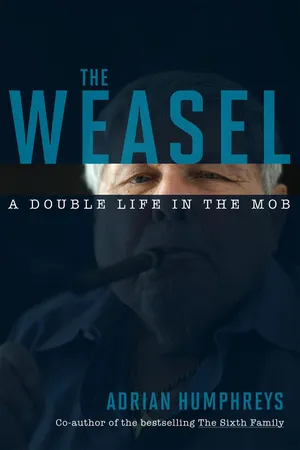

Part One

![]()

Chapter 1

Toronto, 1934

A surprise surge of warmth after a frigid weekend put the city in a good mood on March 13, 1934, and if Beatrice Elkind read the local newspapers that day before entering Toronto General Hospital with labour pains she would have seen a screaming headline—“Accounts Juggled”—about secret payments by city officials; overseas news highlighting fears of war against “Nazi encroachment”; and, to the south in Mason City, Iowa, a story about John Dillinger and Baby Face Nelson hitting the First National Bank, an event that ushered in a new golden age of the American gangster. Beyond the headlines of that day are themes that would have a deep impact on Beatrice and her family—corruption, anti-Semitism and gangster tales—but the only thing on her mind was the struggle inside the delivery room.

Her baby was breeched in her womb, upside down with his chubby legs bent up near his tiny ears. Slippery and stubborn, he had to be dragged out with metal forceps.

Marvin Elkind was a handful before he had even taken his first gasp of air.

Looking at him all tiny, bruised and helpless, no one could have predicted the bizarre life he would go on to live.

“I was born on March 13. I wonder if that was a Friday—Friday the 13th—with all the luck I've had in my life,” says Marvin, now 77.

He chuckles, and his heavy jowls quiver, giving him the look of an English bulldog. Standing five feet six and weighing close to 300 pounds, he is decidedly round, as is his face, with cheeks that ball tight under his eyes into red apples that, in full smile, give him the appearance of a cartoon character.

As he laughs, his hairy chest heaves. From beneath his shirt, which is unbuttoned more than it should be, light glints off the gold chains he likes to drape around his neck. Like most things involving The Weasel, there's a juicy story behind each of them. His enormous sausage fingers are also circled in gold, his pinkies squeezed into chunky rings. Each wrist, too; a heavy gold bracelet around his right and a gold Oscar de la Renta watch around his left. When clenched, his fists are shockingly large, a sign of the boxer he once was, a southpaw with a mixed record in the ring—just as in life.

Despite his age, he maintains a good head of hair, more salt than pepper now, and his once curly locks fall straight and are kept short. A broken front tooth hints at a difficult past.

His eyes, though, are what captivate.

Slate grey, they are a wonder of expression. When laughing, as he does often, his eyes are moist and bright, but when serious or stern, which he has frequent cause to be, they narrow considerably, one slightly more than the other. With eyelids that retract deep under his brow, he conjures the cold look of a shark. His chuckle fades.

“My daughter said I am the luckiest guy in town and I said, ‘What are you talking about? How do you figure that I'm lucky? Look at my life.’ She said, ‘They never got you. All the guys you did jobs on, all you been through, none of them got you. You made it through. You're the luckiest guy in town.’ She might be right in a way,” he says. Then, after a long pause: “I don't feel lucky.”

Marvin was not born on Friday the 13th—it was a Tuesday—but neither was he born into fortunate circumstances, although, at the start, it was hardly an exceptional story for blue-collar immigrants in Toronto, which was then Canada's second-largest city, after Montreal.

Marvin's mother, Beatrice Feldstein, was born in 1911 in Romania and emigrated with her family to Canada. It was a hard journey. Her eldest brother died during the voyage and was hastily buried when the ship pulled into port. The Feldsteins settled in Cabbagetown, a tough neighbourhood near the centre of Toronto, where disputes among residents were settled without the police whenever possible. A high-school graduate, Beatrice was unusually well educated for a poor immigrant Jewish girl at the time. Her handwriting was deemed to be so exquisite that it was showcased at the Canadian National Exhibition. Her abilities earned her a job in the shipping office of Society Shirt. It was there that she met a strapping young janitor who swept her off her feet.

Aaron Elkind, born in 1904, had come to Canada from Russia in 1927 with his younger brother, Morris. They joined their older brothers Sam and Harry, who had arrived earlier when their father, Menachem, was working as a Hebrew teacher in nearby Hamilton, Ontario. Aaron and Beatrice were married in 1931. Three years later, Marvin was born. But, as cheers of mazel tov rang out, there was little joy in the home. Marvin's timing was terrible.

“My father was a bad guy,” Marvin says. “He hung around with bad guys and was always getting into some trouble. My mother didn't know that at the time she married him. When she found out the kind of person he was, it was too late—she was pregnant with me. In those days, abortion was completely unheard of in the Jewish faith and so was divorce if you had a child. She said that if she hadn't had me, she would have left him. So my mother and maternal grandmother always blamed me for the fact that she was with him for so long. The person who always gave her support was Morris, my father's brother.”

Morris Elkind also worked at Society Shirt but was cut from different cloth than Aaron. While Morris always wore a yarmulke, the skullcap of Orthodox Judaism, Aaron shunned the trappings of his faith. As Aaron swept the floors, Morris secured a better job as a cutter, forging a reputation as one of the best. And whenever Aaron had a fight with Beatrice, Morris was there to support her. Aaron was the black sheep, Morris the white knight.

Aaron kept a close eye on the comings and goings at what would later become the Toronto-Dominion Bank on the corner of Dundas Street West and Ossington Avenue. With three friends, he was planning to rob it. It was 1937, and Marvin was three years old.

Their plan was to go for the bank vault at night, to avoid the complications of tellers and customers, guns and getaway cars. But the heist didn't go cleanly. Somebody had ratted and police were waiting.

“The guys had no weapons, but one of them reached for a cigarette and the cops thought he was going for a gun, so they shot him and killed him. My father got away. But we never saw him again. According to my grandmother—my maternal grandmother, who didn't like my father—they suspected he had a beef with police and made a deal to turn the other guys in, and in return he would be allowed to leave the country. He hightailed it back to Russia.”

In Russia, Aaron didn't abandon his sneaky ways.

“It was never proven that this was the case and I hope, I hope, I hope that it isn't true, but my grandmother told me this; my grandmother told me that she found out later that my father got executed in 1946 because the Russians found out he had been selling secrets to the Germans during the war. My grandmother was happy to believe it. She always said that the one good thing he did for us was to leave. I'll tell you how much my grandmother liked him: she told me that when she heard about the robbery and that one guy got killed in it, she was very disappointed to find out it wasn't my father.

“My grandmother was only too happy to believe it, she delighted in it, because it gave her an excuse for me, that his genes were my problem, the reason for my behaviour.”

It is an intriguing revelation: The Weasel might be the son of a weasel.

“Don't think that hasn't come up through my mind many, many times.”

Six months after Aaron fled the bank job, when their rabbi confirmed his betrayal of the family and his move back to Russia, Beatrice married another Elkind, this time Morris, the steady brother.

The new version of the Elkind family moved into a two-storey brown-brick house at the corner of Roxton Road and Harrison Street. Across the road was Fred Hamilton Park, where Marvin played baseball and an outdoor ice rink was flooded each winter for hockey.

Here Beatrice found the stability she craved. About 10 months after she and Morris were married, she gave birth to another son, Stanley. Some seven years later, a daughter, Marilyn, was born.

The family dynamics were hard on young Marvin. Morris was deeply ashamed of his disgraced brother and seemed to see the very image of Aaron in Marvin's face, a daily reminder of his family's shame. Morris, for all his piety, did not extend the love of a father to Marvin.

“My stepfather was a very nice guy to everyone but me. Morris and I didn't get along until the last day of his life,” Marvin says.

There was a streak of Aaron in Marvin. He was rebellious and drawn to the excitement outside Morris's insular world of faith, family and work. Marvin loved physical sports and neighbourhood talk of street toughs.

In kindergarten, Marvin's teacher told him that if his father was not his real dad that meant he was adopted.

“I found out at school you adopted me,” Marvin told Morris that evening.

“No, I didn't,” was the curt reply. “I'm not your father. Don't call me dad.” Not knowing what to do or say, he went to his mother.

“Should I call him ‘Uncle Morris,’ then?” he asked her.

“No, that doesn't sound right.”

“But he told me I can't call him dad.”

“Then call him pops.” And Marvin did, but the distinction between “dad” and “pops” weighed on him, robbing him of the sense of belonging and comfort that he longed for.

Morris could not forget that Marvin was his father's son. Whenever the boy got into trouble, which was often in the years ahead, Morris would say: “I expected it. He's Aaron's son. The apple doesn't fall far from the tree.”

Morris really believed it.

While building his new family, Morris Elkind unleashed his entrepreneurial side. His brother Sam had a successful menswear shop, named Elkind's, and was ready to expand. Morris left Society Shirt and with Sam established a second Elkind's outlet on Dundas Street West. Years later, the stores would grow to become a popular chain of menswear stores called Elk's, but at the start, each day was a struggle for Morris and Beatrice. The long hours drained them. To help, Beatrice's sister and her husband moved into their home.

“My parents had a business and it kept them busy,” Marvin recalls. “I didn't actually see them that much outside of Sundays. They left early in the morning to attend to the business and came home late. And on Sundays I would be getting hell from them for all of the things my uncle was saying that I did during the week. We were mostly looked after by my uncle. He couldn't stand me and I couldn't stand him; and he loved my brother and my brother loved him. Which made me all the madder.

“I didn't like to come home. I didn't like to be home at all. I'd go to a friend's house after school and my parents wouldn't know where I was. I'd stay and sleep there. There was also an alley nearby with old cars in it and sometimes I'd sleep in one of those.

“Not my father, not my mother, not my aunt, not my uncle ever hit me. What they did when they were upset with me was call the school about it and the next day the school would strap me for it.”

Just as Morris and Beatrice were struggling with family strife, they faced a crisis at work as well.

“Their shop was in a strip of buildings owned by Dr. Clendenan. He was their landlord. There's a street named after him, Clendenan Avenue. This was in a neighbourhood called the Junction, and Dr. Clendenan was the wealthiest man in the Junction. He was very wealthy and very WASP. My stepfather was an Orthodox Jew—he always wore a skullcap. They were very, very different men but they were very, very fond of each other.”

Whenever Morris was short of money, he would borrow a few hundred dollars from Clendenan, and he made a point of paying it back the day before it was due. “Always the day before, never on the day it was due, never after,” Marvin says. Dr. Clendenan liked that. But the neighbourhood was in flux. Development pressure was building and rents increased.

Young Marvin would lie awake at night, listening to his parents talk in their bedroom next to his. The couple always spoke to each other in Yiddish. Through the thin walls of their Roxton Road home, Marvin listened as his mother fretted.

“Don't worry,” Morris said. “Dr. Clendenan would never throw us out.” Morris was right. Instead, Clendenan loaned Morris the money to buy the business outright from his brother and, in recognition of the men's special bond, instead of a month-to-month lease like the other tenants, Morris was given a 49-year lease.

“After Clendenan's death, his sons wanted to sell the whole block to a developer, so they got all of the tenants out but my father. He had the long-term lease. They had to buy him out. It was a lot of money. That changed his life. It made him a rich man. He bought a large home on Strathearn Road near Cedarvale Park, invested the rest and lived a semi-retired life.”

While Clendenan's influence was an economic blessing, one piece of advice he gave Morris would have tragic consequences for Marvin. In fact, in any search back through time for the answers to how Marvin Elkind became The Weasel, what happened next must surely rank high.

![]()

Chapter 2

Toronto, 1941

It was weighty stuff for students as young as seven, but a school trip to a local theatre was still better than the usual routine at Dewson Street Junior Public School, even if it was to see William Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice.

The archaic language proved a muddle for many, but the colourful presentation of the character Shylock, a greedy and spiteful Jewish moneylender, caught their attention. The students watched as the nasty Shylock, contemptuously called “Jew,” demanded his “pound of flesh” from his rival, the good-hearted Christian merchant Antonio, when he was unable to repay a debt...