eBook - ePub

No Surrender

A Father, a Son, and an Extraordinary Act of Heroism That Continues to Live on Today

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

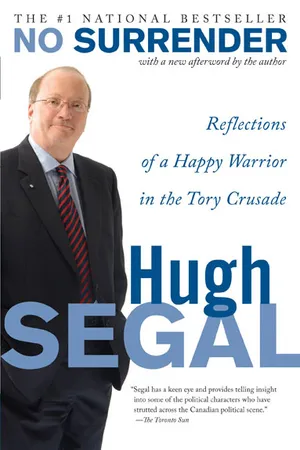

No Surrender

A Father, a Son, and an Extraordinary Act of Heroism That Continues to Live on Today

About this book

Hugh Segal is that rare political animal: a Progressive Conservative partisan who is liked and respected by members of all political parties and who is one of our favorite political pundits. He brings clear-eyed. pragmatic and humorous perspective to this candid and thoughtful memoir, a book that reflects on the true mission of the Progressive Conservative Party and offers insights into Canada's most powerful leaders and their political strategies, past, present and future.

Forthright, wry and unabashedly partisan - like Hugh Segal himself - No Surrender is an engaging personal and political read.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access No Surrender by Hugh Segal in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

FIRE IN THE BELLY

JOHN DIEFENBAKER CAME TO MY SCHOOL in 1962. I was a twelve-year-old student in grade seven, and his message, quite frankly, grabbed me by the throat.

Many people join political parties because of family tradition or deeply held convictions. Many are drawn to a party because of an issue that grinds their axe in a compelling way. My Tory credentials can claim no such noble parentage. I am a Tory because of John Diefenbaker.

When you grow up in a home where your father is a cab driver and many a month the decision was whether to pay the rent or pay the butcher or the druggist, because, God knows, there was no chance we were ever going to pay all three, you live with the perception that many opportunities in this world are closed to you. You live with the expectation that, for people who are poor, there are severe limitations in life.

My grandfather was a Menshevik in Russia before he emigrated to Canada. He supported Kerensky and the social democrats, who had a very short time in office and were not well liked by either the czar or the Bolsheviks. When the Bolsheviks took power in 1917, my grandfather put his finger to the wind and figured it was time to go. His home town, in the region between Odessa and Moscow, changed hands many times. Finally, he stole through Romania to Canada and, a few years later, sent for his wife and children, one of whom was my father. My father arrived in this country around 1920 or 1921, right in the middle of the Russian civil war.

A tailor by trade, Zaida (Grandpa) had a strong commitment to Canadian democracy and to the freedom he had to earn a living, feed his family, be of a minority faith, and accomplish many other things, large and small, that he could never hope to accomplish in Russia. He became an organizer for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, leading strikes on the streets of Montreal, and was a strong supporter of the CCF and the NDP through all his sixty-two years in Canada. As an AFL-CIO kind of leftist, he hated the communists intensely. He saw them as people who would try to break up the Garment Workers’ meetings with baseball bats because they knew that the success of free social-democratic trade unions would mean the end of the Communist Party as a meaningful force in post-depression Canada, which, in fact, is what transpired.

My father was a Liberal because the Liberals were in power when his wave of immigration came ashore and because the power structure in the Jewish community had strong links to the Liberal Party. Primarily because of the ethnic connection, my father had been a sectoral campaign manager for Milty Klein, a prominent MP in the downtown Montreal riding of Cartier.

Even members of the board of my parochial school, United Talmud Torah (or United Bible Study Academy), were heavily involved in the politics of the federal Liberal Party and the Quebec Liberal Party, although some had ties to the Union Nationale.

United Talmud Torah had two major purposes. It ensured that students had, beyond the general curriculum of the Protestant school board of Montreal, a full religious and linguistic curriculum focused on the Bible, commentaries on the Old Testament, and Hebrew language, literature, and history. Second, it would attract only people of one community of faith, which was an added benefit to parents who, in the tradition of first-generation minority groups all over North America, feared nothing more than the marriage of their children out of their faith.

UTT was a bit more worldly than other parochial schools, having many of its non-religious lecturers, English and French, coming in from McGill and Sir George Williams University. Talks by outside visitors were always a special event, and on the eve of the 1962 general election, Prime Minister John G. Diefenbaker came to address the student body and present a copy of his Bill of Rights, a beacon of decency, fairness, tolerance, and opportunity that was particularly well received in a school peopled largely by the children of immigrants.

Diefenbaker’s speech that afternoon was the most compelling non-family event in my life to that point. At parochial school, you spend a good part of your time learning the history of the Jews as, rightly or wrongly, an oppressed people everywhere in the world. And here was Diefenbaker saying that he could have used his mother’s maiden name of Bannerman to avoid discrimination on the Prairies and in law school and politics, but he hung in with Diefenbaker because that was the kind of Canada he wanted. He wanted a country where citizens didn’t have to have a “Mac” or a “Mc” before their name to build some place for themselves in society. He spoke about a Canada that was open to all, a place of opportunity and freedom for people of all ethnic and religious backgrounds.

Dief’s message portrayed the Conservative Party as a populist instrument for all those folks who fell outside the mainstream to find a way into the mainstream, whether they were fishers in the maritimes, small family farmers in eastern Ontario or the prairies, or small businesspeople struggling against the elites. Where they lived and what they did was irrelevant. Dief spoke for the people outside the system.

It was a fascinating message and it struck a chord that has made me embrace the more populist side of the party and of domestic politics ever since.

There was often a fair amount of political discussion around the dinner table at my home. I knew that my grandfather, especially, had no time whatever for the Conservative Party, seen at best as a bastion of the wealthy and those who oppressed others and at worst as an anti-Catholic, anti-Semitic, anti-French WASP enclave within Canada’s political framework. That Friday night at the Sabbath dinner table, I told my family what Diefenbaker had said and how impressed I was both by the prime minister and with his message. I also said that I would support his local candidate in the riding of Mount Royal, a gentleman by the name of Stan Shenkman. Mount Royal had been Liberal forever. Alan MacNaughton, who had been a speaker of the House of Commons, was the incumbent Liberal candidate, had served in Parliament for some time, was quite prominent, and, all in all, was not a bad person.

My grandfather Benjamin Segal, who was a women’s tailor in a factory in the garment business owned by someone in the community who would have been Liberal (they all were), said, “You can’t do that. That’s the bosses’ party.”

I said, “No, Zaida. The Liberals are the bosses’ party. They’re your boss’s party.”

To my proposal to work for Stan Shenkman, my father said, “Over my dead body.” When you’re twelve and your father speaks like that, you know you’re on to something. That Friday night dinner began a long march under circumstances that served me extremely well in the future, namely enjoying the role of the underdog and standing up for the minority in a sea of hostility.

My mother, who simply wanted peace in the family, waded in. “Now look, Hughie. Let’s be frank. What you should do is, you should write Mr. Diefenbaker and Mr. Pearson and Mr. Douglas and Mr. Thomson and ask them all to tell you why you should join their party.” As always, hers was good advice, which I followed to the letter.

It was indicative of how badly organized Diefenbaker’s office was that I received form letters and pamphlets from the NDP, Socreds, and Liberals. From the prime minister, I received a personally signed three-paragraph letter with a long list of reasons why I should join the Conservatives, along with old speeches of his about Quebec, with passages underlined.

My first thought was, “Is this real?” I smudged the signature. It was. All I could think was, “I come from a family of no political consequence. He has no idea who I am. But he actually found time to sign a letter like this to a kid.”

During that period in history, Dief faced a fiscal crisis and a battle with the governor of the Bank of Canada, James Coyne, over who had the final say in monetary policy. History might say he should have spent much more time running the country and straightening out the economy, rather than writing to young people, and that misallocation of time may, in fact, have been one of his great weaknesses as a prime minister. But it was no weakness in the soul he brought to the political process.

Once the letter arrived, neither hypnosis nor sodium pentothal could have changed my fundamental position. I became a Conservative.

In the 1962 campaign, I went door to door campaigning with and for Stan Shenkman, whose slogan was “Stan’s the Man.” We wore bakers’ hats and travelled about in a truck from neighbourhood to neighbourhood handing out free hotdogs. But the anti-Tory parents of Quebec had done their work. We would go into a park full of kids and no one would come near us. You know you’re in deep doo-doo when you give away hotdogs and no one comes.

In that election the Conservative slogan was “Il n’y a pas d’erreur: Diefenbaker / You can’t go wrong with Diefenbaker.” I plastered my school books with these stickers, including the five Books of Moses, which we studied regularly. This was like sticking slogans on a hymnal, which was not considered a good thing to do. I was soon thrown out of class. For me, the incident became a substantial cause célèbre. My parents quickly sided with the teacher and the issue got wrapped up by a brown and broad apology on my part, but it became a very significant part of my self-definition.

Those were the days of the Diefenbuck and the Diefendollar, pegged at ninety-two cents American, which seemed then to be a huge collapse. The Grits gave out Diefenbucks every chance they could to underline what had happened to the economy, which stung Conservatives deeply. On Bay Street and places where Wallace McCutcheon and Donald Fleming had stood for integrity and fiscal probity, the notion that a Conservative government would have played a part in a currency crisis and a run on the dollar did more to affect the standing of the party within the business constituency than any other flaws, creating the kinds of wounds that fester, rarely heal, and, even after decades, can produce a faintly uncomfortable itch.

Diefenbaker argued for the notion that, in the end, it should be the democratically elected prime minister and cabinet who had the final authority over the economy. James Coyne took the contrary view, which has prevailed to this day. To me, at the age of thirteen, the Coyne affair became a symbol of the bureaucratic business complex shutting out people like Diefenbaker even when they were elected, because such people represented the riffraff, all those people who didn’t work on Bay Street or St. James.

In the 1962 campaign, Dief just hung on with a minority. I watched him on TV as he came out of his railway car in Prince Albert with his sleeves rolled up to address the nation. I became intently focused on this one individual as the reflection of all the values that were meaningful to me. My young, idealised views of Diefenbaker have changed over the years, but in those days I was emotionally fixated on his message. Over time, the facts don’t matter. The emotional commitment is fundamental.

I have measured every Conservative leader I have had a relationship with since against the fundamental Diefenbaker mould. They may not have advanced the policy in precisely the way Diefenbaker did or in similar terms, but they were always breaking the establishment hold on the country to bring about greater opportunity and empowerment for people who were left out. That has always been the emotional test: is this leader attempting to open up the mainstream for people who cannot now play for reasons that are not their fault? If the answer is “Maybe” or “I’m not sure,” then I stand back and may not get terribly involved. If the answer is “Yes, that is what this candidate is about,” that’s a strong motivation for me to enlist in the cause, whatever the candidate’s weaknesses or prospects might be.

The identification with Diefenbaker and his message became a means of self-realization, an opportunity for saying when I looked in the mirror, “His beliefs are part of who I am,” which is important for a young person to do. Some people do it through sports, some through rock music, some through academic activity. For me, the path of self-definition became the Conservative Party, a blessing and a debt I can never repay.

I began to see the hold that the Liberal Party had on the establishment in the country and the extent to which people who aspired to the establishment felt they had to be Liberals. It became a self-fulfilling prophecy. It was not hard to build a strong sense of the Liberal Party as always being the party of the established view and of the wealthy or those on the make, while the Conservative Party spoke for everyone else. I saw Diefenbaker and the Conservatives as the voice of a fundamental truth, speaking of a more open society where the old strictures of class, bigotry, and intolerance did not apply.

The most prominent person my family seemed to know was an accountant who had been a Liberal bagman of some sort. My parents asked him to be the toastmaster for the luncheon following my bar mitzvah. Having had a little too much to drink, he stood up and declared, “Before we begin this wonderful repast, I have a few words I’d like to say.”

An hour and ten minutes later in the hot October synagogue basement, my father, who suffered from high blood pressure, was fast asleep at the head table. The rest of the crowd was more than a little fidgety, interested only in getting on to lunch. I knew that when—if—I ever delivered my bar mitzvah speech, no one would care to hear even one-tenth of it. This helped my understanding of what Liberals were about: occupy all the territory and leave no room for the common folk, even if you’re an invited guest yourself. The experience fed into my general view of Liberals as pompous, self-centred people without substance.

I soon began to write long pieces for local community newspapers, attacking those in the community who become “cap in hand” Liberals manipulated by the old Liberal ward heelers and unable to think for themselves. Every attack on Diefenbaker and every instance when the Montreal establishment supported the Liberals, which was always, fed my view of why he was right. The newspapers in Montreal were horrifically Liberal. I wrote letters to the Montreal Star, a terribly Grit paper, defending Diefenbaker and attacking its pro-Pearson and pro-establishment editorials.

All teenagers attempt to establish some measure of individuality and set themselves apart from their parents, older people generally, and from the establishment. It may not strike many people today that being a Conservative is an anti-establishment thing to do, but in Montreal in the early sixties, it was about the most anti-establishment thing anyone could do. To be English-speaking and a Conservative in Montreal was to be a member of the smallest minority conceivable, save one, which was to be English-speaking and a Conservative in the Montreal Jewish community. It was difficult to know which group was smaller, Jews in the Conservative Party or Conservatives in the Jewish community.

The party and the importance of politics generally became a badge of honour. I played hockey for the Ponsard Hockey League in the west end of Montreal. As I skated around in my number 9 Chicago Blackhawks sweater with Conservative stickers on it, other kids would say, “Who cares? This is hockey. It doesn’t matter.” But it does matter. It may be a conceit to think that it matters and it may be a worse conceit to think that your own involvement can make a difference. But if you begin to take the position that your involvement should be determined by what is convenient, you begin to lose some of yourself.

The emotional commitment and my belief in the party were fleshed out by Diefenbaker’s nationalism, which became stunningly apparent around issues like the Bomarc missile question in 1963, when Dief defended Canadian sovereignty and stood up against those who said we had to have American nuclear warheads on our missiles in North Bay and elsewhere.

This was the time of Castro, the October Cuban crisis, Khrushchev, bomb shelters, and people keeping canned food in the basement. Diefenbaker appeared on TV to speak about “these dangerous and serious times.” One Saturday morning, I heard my first air-raid alert, the siren screeching from the roof of a school across a park at the end of our street.

Diefenbaker tried to find a Canadian point of purchase on the issue. Subsequently, it emerged that there was a great debate around the cabinet table as to whether our troops should be put on alert and whether Americans could fly over our territory. Like most Canadians, I was hopeful that Mr. Kennedy would prevail on the missile question, even though it began a policy of paranoia towards Cuba that has survived nine presidents since. Fidel is still in charge and Dief, having tried to find some other kind of policy, is still considered essentially cracked.

History has proved Diefenbaker correct, but his was not the establishment view. The establishment view was that the American military complex had some requirement of us and it was our job to agree. Many people, like the minister of national defence, Doug Harkness, took it as a matter of personal honour that since we had a defence-sharing agreement with the Americans, we should pull together when the time came. Others around the table, notably Howard Green, the minister of external affairs from British Columbia, took a different view. I would have been very much of the Diefenbaker-Green view. In the end, world problems are rarely solved through a testosterone-charged confrontational approach.

The Kennedy administration decided that any Canadian government unprepared to put its military sovereignty at the disposal of General Norstad, engage in high-crisis games of diplomatic and military chicken with the U.S.S.R., or reserve to itself the decision about whether Canada would be a nuclear nation simply had to go.

Short of stuffing ballot boxes themselves, Kennedy’s people did everything else to bring the Diefenbaker administration down. Lou Harris, the Democratic Party’s pollster, was lent to a grateful Liberal Party. The American military held briefings in the basement of the Ottawa embassy for Canadian journalists. Key U.S. publications with broad distribution in Canada savaged Diefenbaker, with a photograph of him on the cover of Newsweek that made him look crazy, which, given his jowly shakiness and piercing eyes, wasn’t too difficult to do. Corporate U.S. defence-industry financial support flowed to the Liberal campaign.

Yet despite all that, the Diefenbaker populist link was so deep that even with high unemployment, currency problems, and massive internal dissension, Liberals could only squeeze out a minority in 1963. The Liberal leader and American choice, Mike Pearson, took two elections to even get into power.

In my youthful exhuberance I could easily believe that the Bomarc missile controversy was a CIA-driven campaign to destroy the Conservative campaign and the party. The Conservatives’ nationalist stand garnered precious little support from the cultural community and the media, aside from the distinguished writing of George Grant. His Lament for a Nation had an indelible effect on me, encapsulating the difference between the Tory vision for Canada and the continentalist, mechanistic, commercialist view.

All this became part of a piece. Given the crisis and the good relationship between Kennedy and Pearson, Liberals were lackeys to American foreign policy. The animosity between the establishment and Diefenbaker and the quiet brokerage routine that served as an excuse for not standing up and being counted all fit neatly. I didn’t have to be a wild-eyed conspiracy theorist to come away with the conclusion that Dief was all that stood between some measure of Canadian identity and the absorption of the country by Yankee commercial and defence interests.

The more Diefenbaker was ridiculed, the more he was attacked, the more passionate I became. I developed a youthful and intense distrust of Peter C. Newman because of his book Renegade in Power, which I saw as the simple hand of Yankee imperialism operating through Newman to destroy the Conservatives by courting the feelin...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- MAY 1991

- 1 FIRE IN THE BELLY

- 2 LOSS OF INNOCENCE

- 3 BLOODIED IN THE MARCH OF THE UNDISCIPLINED

- 4 BRAMPTON LEGIONS

- 5 MUFFLED DRUMS

- 6 FOR NATION AND ENTERPRISE

- 7 ARMCHAIR STALWART

- 8 ANSWERING THE CALL

- 9 DEBILITATING WAR

- 10 FIVE DAYS IN APRIL

- 11 CRUSHING DEFEAT

- 12 TO RISE TO FIGHT AGAIN

- 13 THE BATTLE FOR ’97 AND BEYOND

- EPILOGUE

- AFTERWORD

- INDEX

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Copyright

- About the Publisher