The shift from an industrial to an information society has increased the importance of writing and text production in education, in everyday life, and in more and more professions related to fields such as economics and politics, science and technology, culture and media. Through writing, we create, store, and communicate knowledge, build up social networks, develop projects, inform colleagues and customers, and generate the basis for decisions. The quality of the products of all these processes is often decisive for social participation and resonance, opportunities in the labor market, and professional success.

Nevertheless, many people experience writing and text production as a painful duty or a tedious routine. Beginners as well as experienced writing professionals have to fight in order to find the right words and sentences, they struggle to find the most convincing form and content, and they complain of writing problems or even blocks. Obviously text production places demands on semiotic and linguistic, intellectual and motivational capacities in quite different ways from speaking, which usually seems much more manageable. This gap between the importance of writing and people’s competence raises the questions of how text production can be conceptualized, taught, and learned – and, above all, what writing and text production are in terms of human activities.

This is what the present handbook is about: It brings together and systematizes state-of-the-art research into writing and text production as key human activities and as socially decisive forms of language use. In the next sections of this introduction, we explore the handbook’s approach in more detail.

1 Focus: AL-informed research into writing and text production

In this part of the introduction, we reflect on how applied linguistics (AL) and writing research can benefit from each other. Our focus of attention shifts from a variety of scientific disciplines (1.1.) to linguistics (1.2.), applied linguistics (1.3.), and, finally, the subfields of AL in which writing research plays a key role (1.4.). By doing so, we explain why the AL-informed research of real-life writing requires inter- and transdisciplinary approaches.

1.1 Approaches into writing (research) from many disciplines

Writing and text production are topics among many others that are dealt with in disciplines interested in human thinking and communication, such as psychology, sociology, economics, and media studies. From a linguistic point of view, such disciplines treat extracts of the multilayered phenomena of language use with their own research questions and methods. In doing so, they describe social, organizational, economic, technological, and other aspects of the settings in which individuals and organizations create their offers of communication by producing their texts.

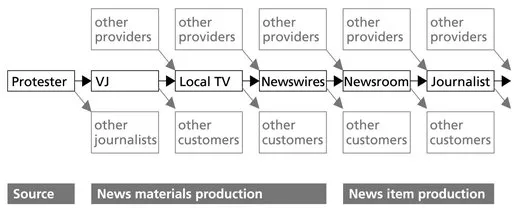

In an investigation of text production in the newsroom, for example, the work done by a particular journalist could be analyzed from economic or linguistic perspectives. When the journalist draws on source materials, she links to both an intertextual chain and a chain of economic value production (Fig. 1).

From an economic perspective, the question arises of how value is created in such production chains (Grésillon and Perrin; Jakobs and Spinuzzi, this volume): at all the stations between source and audience, the news is further contextualized and shaped towards an intended end-user and sold at a higher price. From a linguistic perspective, linguistic utterances such as the quote by the protesters in the above case are edited and recontextualized: cut from their original context, pasted into a new one, and edited in order to fit into the co-text. An applied linguistics approach could investigate how such recontextualizations can be made in a way that the journalists can easily handle the text production task while, at the same time, the original context and meaning of the utterance remain clear for the target audience.

Language, written language, and writing itself are focused on by all the disciplines that work with language and languages as well as with signs and texts in general: semiotics, for example, investigates the way sign systems such as written language and pictures influence one another in multi-semiotic media (e.g., Hess-Lüttich 2002; Bezemer and Jewitt 2009; but also Hicks and Perrin; Prior and Thorne, this volume). Disciplines focusing on language within a cultural region, such as English, German, or Romance studies, investigate the respective language and writing. Literary studies treats writing as the process of generating literature. Language teaching recognizes that writing is a factor in socialization (Beaufort and Iñesta; Gnach and Powell; Poe and Scott, this volume). Stylistics and rhetoric discuss the form and effect of written texts. Composition focuses on the teaching and learning of writing.

Figure 1: The intertextual chain leads from comments of protesters in Lebanon to quotes in a Swiss television news item (Perrin 2013: 28). The chain includes video journalists (VJs) in Lebanon, a Lebanese television company, globally networked newswires, desk researchers at a local TV news provider, and the journalists drawing on the source materials prepared by the desk researcher.

1.2 Linguistics

The central concern of (general) linguistics is language: contrary to semiotics, linguistics just investigates natural language, whether spoken, written, or signed. Different from disciplines such as German studies or Romance studies, it does this beyond the constraints of single languages. It describes languages, rather than judging them as linguistic criticism does, and, different from literary studies or composition, is interested in spoken and written language in all of its uses.

Linguistics has reconstructed language in three research paradigms since the early 20th century: first structurally, as a system of sounds, words, and sentences; then gen-eratively, as a product of cognitive activity; then pragmatically, as a trigger for and trace of social activity in specific settings (such as playgrounds or newsrooms) and contexts (such as domains and related media) of language use. From a writing research perspective, the focus shifted ”from linguistics to text linguistics to text production“ (De Beaugrande 1989). The linguistic sub-disciplines that emerged as a consequence of such developments all deal with the same general objects of study, namely language and language use. However, each discipline adopts its own perspective.

- Sub-disciplines such as phonology, phonetics, morphology, syntax, and text linguistics are based on structural elements of language (e.g., sounds, words, sentences, and texts).

- Sub-disciplines such as semantics, psycholinguistics, sociolinguistics, and pragmatics are based on functions of language (e.g., denoting, thinking, acting, or building communities).

- Sub-disciplines such as conversation analysis, writing studies, discourse studies, and hypermedia studies are based on the environment of language use (e.g., discussions or hypermedia environments).

All the sub-disciplines aim to describe in theoretical terms the regularities that hold for the language users within a language community or for all language users in general.

1.3 Applied linguistics

Similarly to other academic disciplines, linguistics has also developed an applied variant (e.g., Bygate 2005). While the classical academic subjects derive their questions from theoretical considerations, the applied subjects deal with problems from practice and base their treatment of them on theory.

Applied linguistics addresses “problems of linguistic communication” as its “core research object” (Evensen 2013, blurb). As a “user-friendly linguistics” (Wei 2007: 117), for example, it deals with the optimization of language use for certain communicative tasks and domains, including language learning or workplace communication (e.g., Cicourel 2003; Alatis, Hamilton, and Tan 2002; Candlin 2003). It can investigate the repertoires of strategies that individuals or language communities use when they make linguistic decisions (e.g., Cook 2003: 125) in discussions and writing processes (Beaufort and Iñesta; Gnach and Powell; Schindler and Wolfe, this volume). Then, these repertoires can be expanded through teaching and learning processes (Poe and Scott, this volume).

Many applied linguists see their discipline as a variant of linguistics that uses and develops linguistic theories, methods and knowledge to deal with problems of language use in specific fields of application (e.g., Brumfit 1997: 91–93; AILA 2011). Whereas “linguistics applied” investigates practice to clarify theoretically relevant questions, applied linguistics starts its research projects from practically relevant questions (Widdowson 2000; see also Jakobs and Spinuzzi; Oakey and Russell; Poe and Scott, this volume).

As a discipline (e.g., Brumfit 1997), applied linguistics develops subdisciplines related to domains whose language use is socially significant, differs noticeably from language use in other domains, and is related to domain-specific problems. Examples of such subdisciplines include:

- Legal linguistics deals with language use in law practice, where language creates legal obligation.

- Forensic linguistics deals with language use in legal investigations and judicial practice, where language can yield alibis and evidence.

- Clinical linguistics deals with language use in therapy for language, communicative, and other related disorders.

- Organizational linguistics deals with language use in occupational settings, where language guides organizational processes of value creation.

All of these subdisciplines deal with verbal, para-verbal and non-verbal communication, with spoken and written language, and with all the emerging hybrid forms. Therefore, in addition to domain-related subdisciplines, theoretical and applied linguistics have developed cross-section subdisciplines oriented towards prototype modes of language use, such as speaking and writing.

1.4 AL-informed writing research

From an applied linguistics perspective, writing research has become a cross-section subdiscipline that is oriented towards analyzing, understanding, and improving writing as a key mode of real-life language use. In practice, this AL-informed writing research mostly combines approaches from applied linguistics with knowledge from other disciplines, such as psychology and sociology. Investigating writing in context has long been seen as a research enterprise that requires multi-perspective approaches in order to develop as vivid as possible a reconstruction of the mental, material, and social activities involved (Berkenkotter and Luginbühl; Devitt and Reiff, this volume).

Today, writing research conceptualizes writing as the production of texts, as cognitive problem solving (e.g., Cooper and Matsuhashi 1983), and as the collaborative practice of social meaning making (e.g., Gunnarsson 1997; Prior 2006). It investigates writing through laboratory experiments and field research. The experimental research explains cognitive activities such as micro pauses for planning. The field studies provide knowledge about writing processes in settings such as school and professions. The present state of research results from paradigm shifts such as from product to process and from the lab to the field (e.g., Schultz 2006).

- In an early paradigm shift, the focus of interest moved from the product to the process. Researchers started to go beyond final text versions and authors’ subjective reports about their writing experience (e.g., Hodge 1979; Pitts 1982). Draft versions from different stages in a writing process were compared. Manuscripts were analyzed for their traces from revision processes, such as cross-outs and insertions. This approach is still practiced in the field of literary writing, where archival research reveals the genesis of masterpieces (e.g., Bazerman 2008; Grésillon 1997; Grésillon and Perrin, this volume).

- Another paradigm shift took research from the lab to the “real life” (Van der Geest 1996). Researchers moved from testing subjects with experimental tasks (e.g., Rodriguez and Severinson-Eklundh 2006) to workplace ethnography (e.g., Bracewell 2003), for example to describe professionals’ writing expertise (e.g., Beaufort 2005: 210). Later, ethnography was complemented by recordings of writing activities (e.g., Latif 2008), such as keylogging. The first multimethod approach that combined ethnography and keylogging at the workplace was progression analysis. Such approaches conceptualize their object as writing in complex, dynamic, and co-adaptive contexts.

Writing research in the field of journalism, for example, sees newswriting as a reproductive process in which professionals contribute to glocalized newsflows by transforming source texts into public target texts. This happens at collaborative digital workplaces (e.g., Hemmingway 2007; Schindler and Wolfe, this volume), in highly standardized formats and timeframes, and in recursive phases such as goal setting, planning, formulating, revising, and reading (Fig. 3). Conflicts ...