![]()

Section 1: Critical responses to Exhibitions, conferences and publications

dp n="14" folio="" ? dp n="15" folio="" ? ![]()

Jessica Palmieri

The Legacy and Topicality of Futurism

Giancarlo Carpi and Antonio Saccoccio organized an international symposium, held at the Centro Culturale Elsa Morante in Rome’s EUR on 11–12 April 2013 to present new research pertaining to the legacy of Futurism. Eredità e attualità del futurismo brought together scholars and artists in order to discuss a wide range of ideas and address concerns. Spanning two days, eight loosely organized panels were punctuated by Dis/Continuità futurista, a small on-site exhibition of documents, as well as never-publicly-screened interviews of Tullio Crali, Giuseppe Sprovieri and Giannina Censi from the archive of Carlo Erba. The conference was presented with the support of Roma Capitale and the Università Tor Vergata di Roma.

Featuring broad, overarching themes, the symposium took into account Futurist artists and archives deserving further study, as well as contemporary artists working in dialogue with Futurist theory, including transhumanism as a realization of Marinetti’s idea of an uomo moltiplicato (Extended Man).

It was notable that some scholars present were influenced by the cultural and political climate of Italy in the 1960s and 1970s. Such was the case for Giovanni Antonucci, a former professor of theatre studies at the University “La Sapienza” in Rome. His teacher, Giovanni Macchia, thought it strange that Antonucci should take an interest in studying Futurism just as he had done, following a visit to an exhibition of Prampolini in the 1960s. While reasoning that all forms of Futurism were a type of spectacle, he brought into question the often-cited text, Futurist Performance by Michael Kirby (New York: Dutton, 1971). Citing interventionism as a hallmark of Neo-Futurist theatre and happening, Antonucci singled out works by Carmelo Bene, one of the most celebrated figures of the Italian avant-garde in the second half of the twentieth century, and the Bread and Puppet Theater, a political group founded in 1963 in New York City.

Regarding the same historical moment, and in perhaps the most unexpected presentation of the conference, Paolo Tonini (L’Arengario Studio Bibliografico) in his paper, Al di là del futurismo: Libri, riviste e immagini del Movimento ’77, addressed the correlation between Futurist writings and those of the Movimento del’77. He cited similarities in literary works such as Fillia’s L’ultimo sentimentale (Torino: Edizioni Sindacati Artistici, 1927) and L’ultimo uomo by Guido Andrea (Roma: Savelli, 1977), and highlighted the importance of the literary and political legacy of Futurism. Tonini also spoke about the Foundation Manifesto of Futurism , its different versions before the publication in Le Figaro in 1909, and how the aesthetic and political reception of Futurism have always been entwined.

Luigi Tallarico (Centro Studi Futurismo Oggi) demonstrated this continuity of reception in the perpetual reinvention of the universe and argued that every generation should invent their own world without a break in continuity. He expounded that, historically, critics of Futurism interpreted the movement philosophically or based their criticism on the prophetic importance of their ideas.

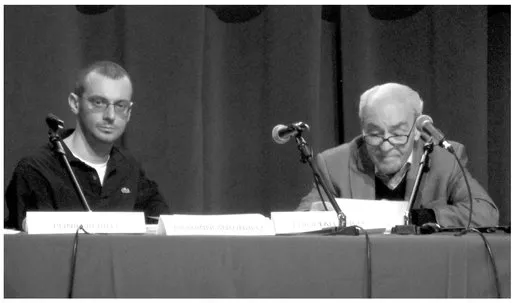

Fig. 1. Luigi Tallarico (right) and Antonio Saccoccio (left) during the international conference, Eredità e attualità del futurismo, in Rome, 11–12 April 2013.

Plinio Perilli (independent scholar) also discusssed the evolution of Futurism Studies and caused a spirited discussion regarding the merits and use of clichés, especially with regard to Fascism and Russian Futurism. Maurizio Scudiero (Archivio Depero) brought up the fact that the study of theatre is quickly evolving to include new media and pointed out that generalizations abound in the field.

Contemporary artists and archives of Futurist art were also presented by speakers. Among historic artists who received particular attention were Gerardo Dottori, as discussed by Massimo Duranti, President of the Gerardo Dottori Archives, and Bruno Munari, in an extensive overview of his œuvre given by Miroslava Hájek (Studio UXA). Duranti also addressed the topic of “Futurist aristocracy” and opened up a discussion on various Futurist artists of predominantly regional significance. He also mentioned that the Studio Dottori is open to visitors by appointment but is currently undergoing reconstruction.

Next, Maurizio Scudiero energetically presented the advertising work undertaken by Fortunato Depero, underscoring the fact that the Futurists had ideas which technology was unable to keep up with, an example of which were the transforming costumes of both Depero and Mikhail Larinov. Scudiero also pointed out that street art can find its early beginnings in the chalk-cartoon-transferred ads publicizing Depero’s Balli plastici. Meanwhile, Joan Abelló Juanpere (Universitat Pompeu Fabra di Barcellona) spoke about the influence and impact of Futurism on Catalan artists. Giacomo Balla proved to be the primary inspiration for contemporary artists such as Antonio Fiore, whose ‘Cosmic Futurism’ was discussed by Andrea Baffoni (Università degli Studi di Perugia). Likewise, Stefano Gallo (Università Tor Vergata di Roma) related how the artist Bruno Aller relied on Balla’s abstract figuration, in works such as his Ritratto di Emilio Villa, 2008.

In a separate argument, transhumanism was introduced as a contemporary iteration of Marinetti’s concept of the uomo moltiplicato. Carolina Fernández Castrillo (Universidad a Distancia de Madrid) and Riccardo Campa (Universytet Jagelloński, Kraków) both drew attention to this topic in their presentations. Castrillo illuminated the adoption of bioengineering as a practice by contemporary artists such as Eduardo Kac in his genetically modified GFP Bunny and in the permutations found in the films of Matthew Barney. Castrillo pointed out that genetic modification seen in the confluence of science and art in the twenty-first century is similar to the metallic animals discussed in Balla and Depero’s Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe (1915). Campa presented a Futurism-after-Futurism as seen in the evolution of artificial limbs, human and genetic enhancement, smart drugs and in the field of plastic surgery. In showing the evolution of prosthetics, Campa addressed the complicated, often uncomfortable, discourse surrounding these technological innovations.

Other instances of the contemporary application of Futurist theories were presented in talks given by Rosella Catanese (Università di Roma “La Sapienza”), who looked to the cultural theories of Paul Virilio in relation to speed and Futurist cinema. Lorenzo Canova (Università degli Studi del Molise) referenced Umberto Boccioni’s installation art and named some heirs of his practice: Lucio Fontana, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol, all of whom also used tactilism and mass-media in their installations.

Finally, Antonio Saccoccio (Università Tor Vergata di Roma), a co-organizer of this conference, presented the vita simultanea futurista and its manifestation in contemporary culture, as exemplified by the fetishization of multitasking in Western societies. The other co-organizer, Giancarlo Carpi, discussed the fetishization of art by giving life to the object itself, which then becomes like a living organism.

Overall, it was apparent that there are many resources available to scholars in order to advance the understanding of the Futurist movement and that each generation is continually reinterpreting its legacy. The conference presented interesting themes and artists and emphasized the need to break out of antiquated molds and trends in scholarship in order to address the full complexity of the Futurist movement. This conference, while aiming to look at contemporary iterations of Futurism and Futurism Studies, was nonetheless punctuated by traditional notions of regionalism and continued to signal Futurism’s relationship with Fascism as a roadblock to our understanding of the movement.

![]()

Andrei Ust...