eBook - ePub

Diagnostic Enzymology

- 212 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Diagnostic Enzymology

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Diagnostic Enzymology by Steven Kazmierczak, Hassan M. E. Azzazy, Steven Kazmierczak,Hassan M. E. Azzazy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Biochimica in medicina. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Angiotensin converting enzyme

1.1 Case studies

1.1.1 Patient A

A 55-year-old White male presented with fatigue, dizziness, pressure headaches, and facial numbness. Initial evaluations revealed some neurological abnormalities, including bilateral hand pain, progressive dizziness, and increased sensitivity to sound. His medications included meclizine, a headache medicine containing butalbital, and topiramate.

Neurological evaluation 3 months after onset of symptoms revealed blunted facial sensation and decreased vibratory sensation in his finger tips and toes. Position sensation was intact. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed mild, nonspecific white matter changes most likely representing microvascular disease. However, demyelinating disease could not be excluded. Carotid ultrasound studies were normal.

Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed a normal angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) <14 U/L, and increased protein of 0.69 g/L (elevated), and negative for oligoclonal bands.

1.1.1.1 Discussion

Neurosarcoidosis is a rare manifestation that occurs in 5% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis. Lesions mainly involve the optic and cranial nerves and the spinal cord. This patient presented with fairly non-specific neurological complaints. The differential diagnosis includes various inflammatory, infectious, and autoimmune disorders, including neurosarcoidosis and multiple sclerosis. The low ACE level and lack of oligoclonal bands in the CSF made these diagnoses less likely, and the patient was scheduled for additional follow-up. One month after the evaluation the patient reported considerable improvement and discontinued his various medications. Based on the laboratory findings, most of the pathological processes could be excluded and given the patient’s improvement, further follow-up was not deemed necessary.

1.1.2 Patient B

A 41-year-old African-American female who was known to have sarcoidosis with pulmonary involvement presented for evaluation of worsening dyspnea, blurred vision, and recurring headaches. Her diagnosis of sarcoidosis was made 2 years previously by mediastinoscopy, which revealed the presence of non-caseating granulomas. At this visit, her pulmonary function tests were normal and there was no evidence of hypoxemia. Her only medication was hydroxychloroquine, which is useful for the treatment of sarcoidosis, particularly that of the skin.

Laboratory evaluation showed a normal cell blood count (CBC), except for elevated eosinophils (7%), and a normal metabolic panel. Her serum ACE was mildly elevated (53 U/L, normal < 49 U/L) and her soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R) levels were normal. The patient was prescribed a course of prednisone and was scheduled for a follow-up appointment.

1.1.2.1 Discussion

This patient’s disease activity was evaluated and, on the basis of her test results, was not severe. The mildly elevated ACE level was consistent with the established diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Measurement of sIL-2R levels has been suggested to play a role as a marker for pulmonary disease activity, but there is no relationship between sIL-2R levels and response to treatment. This patient’s sarcoidosis seemed to be properly controlled by hydroxychloroquine, but of concern were the various side effects caused by this drug, which include headaches, blurred vision, and more serious ocular toxic effects. Given this patient’s increased symptomology and her recent emergency department visits, her hydroxychloroquine therapy was transiently stopped and her condition improved with prednisone therapy.

1.1.3 Patient C

A 41-year-old female was referred to the clinic by her primary care physician for uveitis, parotitis, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The patient had been previously healthy but had a worsening cough over the past 3 months, along with swollen knees, ankles, and parotids with dry mouth. In addition, the patient had unintentionally lost significant weight (18 kg) and had recurring fevers 39°C with night sweats. She was given a short course of antibiotics by her primary care physician but developed diffuse erythematous rash 1 week after stopping the antibiotics.

Physical examination was normal. Her laboratory results were unremarkable except for elevated calcium (3.3 mmol/L), aspartate aminotransferase (49 U/L), alkaline phosphatase (348 U/L), and ACE (195 U/L).

1.1.3.1 Discussion

This patient presented with a multisystemic process involving the mediastinal lymph nodes, uveitis, cough, fever, and weight loss in the past 3 months. The possible diagnoses included malignancy (non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma), sarcoidosis, or fungal infections. On the basis of the elevated ACE and calcium levels, sarcoidosis seemed to be the most likely diagnosis. In fact, the symptoms described are most consistent with Heerfordt’s syndrome, a rare manifestation of sarcoidosis, which involves uveitis, parotiditis, and chronic fever. This diagnosis was further confirmed by bronchoscopy findings. Steroid treatment was initiated and the patient’s condition improved, but her ACE level remained elevated (>100 U/L) during follow-up visits.

1.2 Biochemistry and physiology

1.2.1 Physiological function

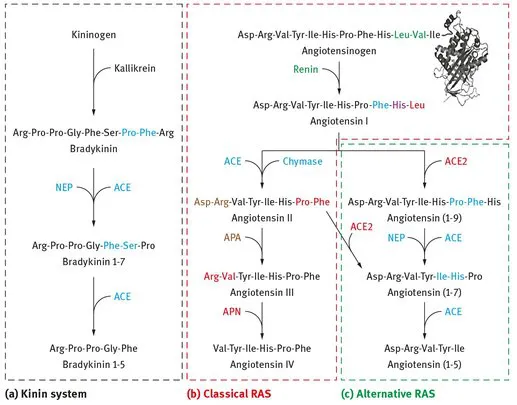

Angiotensin I converting enzyme (ACE; EC 3.4.15.1) is a type-I membrane-anchored zinc metallopeptidase of the M2 family with diverse physiological functions [1]. Isolated for the first time in 1956, ACE is known to be mainly involved in blood pressure regulation and electrolyte hemostasis through the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) by acting as a dicarboxypeptidase in bradykinin inactivation (Figure 1.1a) and angiotensin II production (Figure 1.1b) [2]. Bradykinin is a vasodilator whereas angiotensin II is a vasoconstrictor. As a result, ACE promotes vasoconstriction and is a target for treating hypertension and associated cardiovascular disorders [3]. Other substrates of this enzyme include angiotensin (1–7), hemoregulatory peptide N-Acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro, gonadotropin-releasing hormone, luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone, substance P, enkephalins, β-neoendorphin (1–9), and neurotensin [4–6].

ACE2 or hACE, a human homolog of ACE and a new component of the RAS system, was discovered in 2000 by two independent groups [7, 8]. It has been demonstrated that ACE2 also acts as a carboxypeptidase but only cleaves a single amino acid from the C-terminus of angiotensin I to yield angiotensin (1–9) and angiotensin II to yield angiotensin (1–7) (Figure 1.1c) [7]. Among these two pathways of the so-called “alternative RAS,” cleavage of angiotensin II is 400-fold more kinetically favored over that of angiotensin I [9–11]. Animal studies have shown that angiotensin (1–7) has antihypertensive, anti-arrhythmic, anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic, antithrombotic, anti-trophic, and cardioprotective properties [11]. Therefore, the protective effects of the “alternative RAS” axis counter-regulate the deleterious effects of the “classical RAS” axis, thereby preventing overactive RAS-associated diseases, including hypertension [12]. Currently, ACE2 is still under research and is not used for diagnostic purposes. As a result, the remainder of this chapter will focus on ACE only.

1.2.2 Biochemistry and molecular forms

ACE is expressed as two isoforms, somatic (sACE) and testis (tACE), derived from a common gene by alternative splicing. The larger somatic isoform (1306 AA, 150 kDa) consists of N- and C-terminal catalytic extracellular domains, each containing the zinc-binding motif HEMGH (His-Glu-Met-Gly-His), whereas tACE (732 AA, 83 kDa) consists of a single extracellular domain almost identical with the C domain of sACE [13, 14]. Differences in structure and function of the N and C domains of sACE imply that the two active sites each have independent activity.

Figure 1.1: Schematic illustration highlighting the enzymes, their substrates, and their sites of cleavage in the kinin system (a), classical renin-angiotensin system (RAS) (b), and alternative RAS (c). Colored amino acids represent the site of cleavage for the color-matched enzymes. ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ACE2, angiotensin converting enzyme 2; NEP, neprilysin; APA, aminopeptidase A; APN, aminopeptidase N.

Although ACE has been known for some time, obtaining a crystal structure of this enzyme has proved challenging due to variation in surface glycosylation, rendering it difficult to crystallize. As a result, the first X-ray crystal structure of human tACE complexed with lisinopril, a commonly used ACE inhibitor, was not reported until 2003 after modification of the carbohydrates to minimize oligosaccharide-based heterogeneity [15]. The structure of tACE was reported to be an overall ellipsoid shape with a central groove dividing the molecule into two subdomains. Covering the top of the molecule is an N-terminal “lid” formed by three α-helices that is believed to restrict access of large polypeptide to the active site cleft. This structure is predominantly helical with 27 helices and only one β structure located near the active site in six relatively short strands that account for 4% of all residues.

Both domains of ACE are heavily glycosylated, with the C domain containing seven and the N domain containing ten potential N-glycosylation sites [16]. Investigations into the role of glycosylation in the N domain have revealed that C-terminal glycosylation is vital for folding and processing, whereas N-terminal glycosylation maintains its high level of thermal stability [17]. It is suggested that this higher degree of glycosylation, combined with a greater number of α-helices and increased proline content, contributes to its thermal stability (Tm = 70°C) compared with the C domain (Tm = 55°C) [16, 18]. Functionally, although the two active sites of sACE are able to cleave angiotensin I and bradykinin in vitro, the C domain is the major site of angiotensin I cleavage in vivo [19–23]. In addition, the two domains exhibit differences in chloride activation and specificity for various inhibitors [20, 24, 25].

Chloride-dependent enzyme activation is an unusual characteristic of ACE that is shared only by a handful of other enzymes [26]. The C domain of sACE requires chloride in a pH-dependent manner for its catalytic action on angiotensin I, whereas the N domain retains 45% of its catalytic activity on bradykinin in the absence of chloride [27]. In addition, maximal substrate turnover is observed at 200 mM of chloride for the C domain, but at only 20 mM of chloride for the N domain, which also decreases at chloride concentrations greater than 20 mM [28]. The crystal structure of tACE reveals the location of two buried chloride ions separated by 20.3 Å [15]. Activation of ACE by other monovalent anions is also possible, with chloride and bromide having the highest affinity, whereas iodide and fluoride have a ten- to 100-fold lower affinity [29]. The order of activation of ACE by monovalent anions is chloride > bromide > fluoride > nitrate > acetate. The mechanism of ACE chloride activation is hypothesized to be through stabilization of the enzyme-substrate complex by inhibition of salt bridge formation between R522 and D465 because ion pairing between R522 and the c...

Table of contents

- Kazmierczak, Azzazy • Diagnostic Enzymology

- Also of Interest

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- List of contributing authors

- Table of Contents

- 1 Angiotensin converting enzyme

- 2 Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase

- 3 Aldolase

- 4 Alkaline phosphatase

- 5 Aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase

- 6 Creatine kinase, isoenzymes, and isoforms

- 7 Gamma-glutamyl transferase

- 8 Lactate dehydrogenase

- 9 Pancreatic lipase

- 10 Natriuretic peptides

- Index